Chinese companies are snapping up foreign commercial real estate assets, but the nature of the buyers is evolving.

The 47-storey Waldorf Astoria Hotel stands only a few blocks away from famous New York icons such as 5th Avenue, Madison Square Garden and Grand Central Station. Occupying a central location in Manhattan, the hotel has played host to countless high-profile events that have seen US diplomats, foreign dignitaries and celebrities mingle in ballrooms boasting famed Art Deco-inspired fixtures and décor.

Although the hotel regularly makes headlines when it hosts noteworthy guests, in October 2014 the Waldorf Astoria made the news for very different reasons when Anbang Insurance Group formally purchased the building for a cool $1.95 billion. The bottom line turned some heads, but the Obama administration’s decision to break with tradition and stay at the nearby New York Palace Hotel for September’s UN General Assembly drew particular attention. As a Chinese company buying property in the United States, Anbang suddenly found itself a victim of tense bilateral relations.

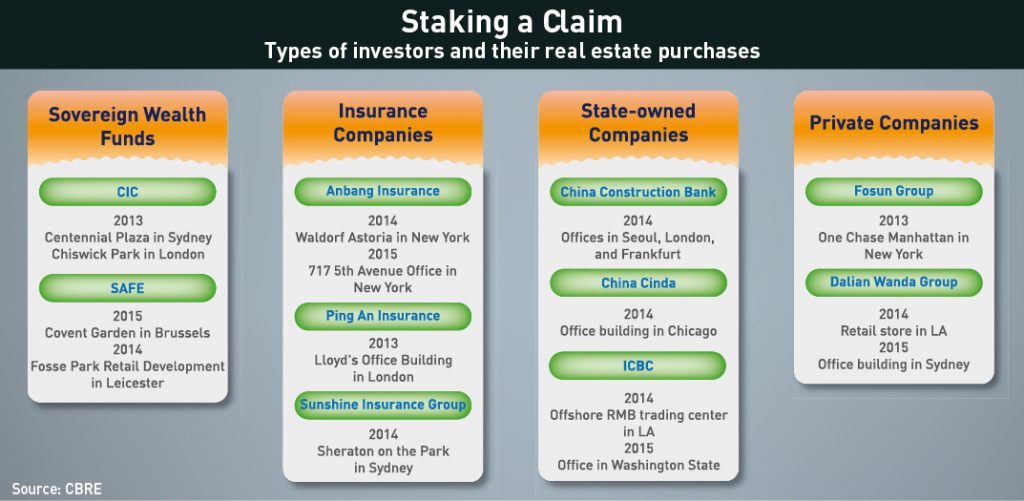

Anbang’s purchase stands out for the controversy it created, but, in reality, the Waldorf Astoria deal only represents one foreign commercial real estate purchase among the many others carried out by mainland Chinese investors over the past few years. Other notable real estate acquisitions made by Chinese firms include One Chase Manhattan and the luxurious Baccarat Hotel in New York, a choice plot of land in Beverly Hills and the upscale Sheraton on the Park Hotel in Sydney.

The list of expensive acquisitions continues to grow and, with Chinese foreign commercial property purchases totaling over $10 billion in 2014, the trend looks set to continue. “Chinese capital will increasingly move abroad as investors look to expand their portfolios and enhance their investment returns in stable property assets,” says Ada Choi, Senior Director of Research at CBRE Asia Pacific, an American commercial real estate company.

Laying the Foundations

One catalyst for this trend was the 2008 financial crisis, which originated in the US subprime housing market before spreading to Europe and endangering markets worldwide. The rapid and sustained drop in real estate prices in the United States and Europe gave Chinese investors an opportunity to purchase assets that had lost a significant chunk of their original value.

Adding strength to Chinese investors’ positions was the rising value of the renminbi, which made solid gains on the US dollar and the British pound from 2008 to 2014. Despite economic uncertainty roiling developed Western markets, Chinese investors continued to see real estate in mature markets as a safe investment. David Ji, Head of Research and Consultancy for Greater China at Knight Frank, says, “In mature markets such as New York or London, it is relatively safe to invest in a high-priced office building. You are guaranteed that these units will be leased to quality tenants such as banks, financial institutions or multinational companies, thereby ensuring reliable rent.”

Significant regulatory overhaul also eased restraints on Chinese capital seeking stronger returns in overseas markets. In 2013, China’s National Development and Reform Commission increased the overseas investment approval limit from $100 million to $1 billion, which allowed companies to make investments under $1 billion without needing prior government consent. Then in 2014, the Ministry of Commerce further loosened restrictions on foreign investment by eliminating prior approval requirements for the majority of outgoing investments.

These two landmark changes marked substantial steps in China’s “going out” strategy, which combines incentives and regulatory overhaul to encourage firms to be global in their outlook and ambitions. Research conducted by CBRE illustrates how rapidly Chinese firms have responded to Beijing’s global push.

In 2009, Chinese outbound real estate investment only reached $600 million. But the next year a new trend began as foreign commercial real estate investments steadily increased. The total figure for outbound commercial real estate investments climbed to over $10 billion in 2014, representing a dramatic increase in only five years. While different cities offer varying risks and returns, most Chinese firms have chosen to make their first forays into real estate in the relative safety of ‘gateway cities’.

These cities, mainly located in the US, UK and Australia, are seen as the most attractive and reliable investment opportunities for inexperienced property investors. Familiar names such as London, New York, San Francisco, Washington, Los Angeles, Melbourne and Sydney offer Chinese investors a comfortable return on investment while they gain a foothold in new, developed markets. Moreover, the economic, political, and regulatory stability afforded in these cities ensures that assigned investments can’t be rolled back. Once they’ve gained a better understanding of local regulations, companies then feel more comfortable to push outward into less developed markets.

“Failed investments in emerging economies have reinforced the belief that mature markets represent the safest investments,” says Ji. Unsurprisingly then, according to a 2015 CBRE Research Report, London accounted for 52% of all Chinese commercial real estate purchases in Europe in 2013 while the purchase prices of hotels and offices in New York and Los Angeles accounted for approximately half of all investments in US real estate.

Unlocking Potential

Regulatory overhaul has been overwhelmingly successful in allowing companies to diversify their investments and spend their capital abroad, with mainland insurance companies in particular benefitting from relaxed rules.

“Chinese insurance companies have been quite active recently,” says Junwei Lu, a Senior Associate with Berwin Leighton Paisner LLP. “These companies have traditionally been conservative, but with recent law changes relaxing investment regulations, insurers have sought to diversify their assets into safe havens such as the US, UK and Australia.” Mainland insurers’ investing power was unleashed in late 2012 when regulators allowed insurance companies to purchase real estate in 45 different countries. Subsequent reforms enabled insurers to invest up to 30% of their assets in real estate, with 15% of such investments overseas.

As a result, mainland insurance companies have been some of the biggest movers in recent years. Ping An Insurance purchased Lloyd’s Building in London for $387 million in 2013, while Sunshine Insurance Group bought the 557-room Sheraton on the Park in Sydney for $401 million in 2014. Parking money in high-class hotels and cutting-edge offices guarantees that insurers will earn solid, if not spectacular, returns.

Wielding the country’s considerable foreign exchange reserves, China’s two largest sovereign wealth funds—China Investment Corporation (CIC) and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE)—have also made their presence felt in global markets.

CIC has increasingly targeted Australia. Following its purchase of the towering Centennial Plaza in 2013, CIC purchased an additional nine office properties from Morgan Stanley in 2015. SAFE has made a string of purchases throughout Europe, with a 70,000 square meter office complex in Belgium standing out for its sheer size. With combined assets of an estimated $1.3 trillion, these two funds will continue to make waves in commercial real estate for the foreseeable future.

State-owned enterprises have also made significant plays in the foreign real estate market, with Sinopec, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), and the People’s Bank of China making purchases in key cities throughout the US, UK and Australia. These state-owned corporations are at the forefront of China’s “going out” strategy and, as such, purchase foreign properties with eyes on gaining access to new lucrative markets. For example, China’s largest petroleum and petrochemicals company Sinopec recently purchased an office in Houston, Texas that will allow closer collaboration with local partners.

As China’s largest bank, ICBC has rapidly expanded its operations in the United States after opening its first New York-based office in 2008. In 2014, ICBC formed the US’ first offshore RMB trading center in Los Angeles, and in September 2015 announced plans to open another branch office in Seattle, Washington.

Yet for all their activity, these institutions are actually relative late comers to the field. “Private companies have been involved in foreign markets for longer than many of the big institutions,” says Lu, a fact attributable to a much lighter regulatory burden.

Of these, Dalian Wanda Group has emerged as one of the most aggressive. In addition to buying multiple cinema chains around the globe, it has plans to develop a five-star hotel next to the Thames River in London. These high-profile acquisitions fit into China’s “going out” plan as well as the company’s larger diversification strategy that has seen it purchase stakes in a European soccer club and acquire a Hollywood film company. Additional plans to construct the world’s third-largest skyscraper in Chicago highlight the extent of Dalian Wanda’s global ambitions.

Another privately held company, the Shanghai-based Fosun Group, has made over 10 real estate purchases in the last two years including 28 Liberty Street—formerly One Chase Manhattan—near Wall Street and a new residential tower near the Empire State Building. With investments in a wide variety of industries and asset classes, Fosun Group and Dalian Wanda have demonstrated that they have a greater appetite for risk than insurers, banks and sovereign wealth funds. Rather than simply parking money in buildings and waiting for returns, these private companies proactively use their real estate assets as they expand into new industries.

Taken together, institutional investors, developers and insurance companies constitute what Ji of Knight Frank calls “three waves,” but the market is evolving once again. “Now the fourth wave is a mixed bag of small-to-mid cap investors, wealthy individuals, private equity funds and regional companies who are seeking more profitable markets overseas. This fourth wave of investors is less predictable than the first three,” he says.

Naturally, this diverse assortment of investors have different motivations and target different types of real estate based on their interests and available capital. What remains clear is that commercial real estate will continue to be a target for investment in the coming years. One important factor to consider, says Ji, is that, while a new fourth wave is beginning to delve into foreign markets, the first three waves have not stopped buying and investing in properties.

Long-term Stay

The list of recent commercial purchases by private companies, insurers, sovereign wealth funds, and SOEs illustrates how quickly Chinese appetite for real estate has grown. While real estate in mature markets is generally perceived as a safe investment, commercial real estate encompasses a broad range of asset types that includes office buildings, hotels, distribution warehouses, assisted living centers and student housing. Among these, office buildings are often the easiest asset class for new Chinese investors to purchase. “Offices are quite straightforward,” says Lu. “Investors can purchase the office property and use the asset to generate a stable income stream for the next 10 to 20 years.”

It is this simplicity and stability that has lured Chinese companies towards profitable office building purchases in gateway cities. Fosun Group’s $725 million purchase of an office building in 2013 garnered significant press, but privately-owned companies as well as state enterprises have also made significant buys in Houston, Chicago, Seoul, London and Frankfurt. These properties can then be leased out to generate a stable revenue stream or kept in-house for use in expanding operations abroad, as with Sinopec in Houston and ICBC in Europe and the US.

Office buildings may be the safest, most easily managed commercial real estate assets, but the purchase of a luxury hotel brings the prestige and global name brand recognition that ambitious companies crave. The cachet of the renowned Waldorf Astoria or the elegant Marriott on the Champs-Elysees can provide the intangible boost a company needs to succeed internationally.

Naturally, these high-profile assets are out of the price range of all but the largest companies, but the potential returns on a hotel property are so great that even smaller investors are getting involved. “Hotels provide effective diversification of investment assets, and, in large gateway cities such as Los Angeles and Sydney, there is always a demand for rooms,” says Ji.

In addition to stable returns, Chinese-owned hotels have a leg up over foreign firms in drawing on the ever-increasing number of Chinese tourists abroad. According to the China Tourism Research Institute, over 61 million Chinese traveled during the first half of 2015, a figure that represents a 12.1% increase over the same period of 2014.

With Chinese continuing to travel and study and move abroad, Choi is confident that hotel assets will remain attractive options for investors. “Capturing the increase of Chinese travelers around the globe will continue to be a motivating factor in mainland Chinese companies’ hotel purchases,” he says.

Offices and hotels are the glitzy, high-profile buildings that carry large price tags and generate significant returns, yet their more humble counterparts, retail stores and warehouses, offer buyers another set of advantages. “Companies that purchase stores and warehouses are often looking to capture technology and knowhow that they can then bring back to mainland China. By getting involved in retail and logistics overseas, Chinese companies can gain an advantage over competitors at home,” says Lu.

Dalian Wanda’s $420 million purchase of a retail space in Los Angeles in 2014 is one clear example. Fosun Group has also announced plans to redesign downtown Manhattan’s 28 Liberty Street with new restaurants and high-end retail stores. Although home appliance giant Suning has yet to expand abroad, its recent advertisements in New York’s Times Square beckoning pedestrians to visit “Suning Smart City,” a cosmopolitan zone blending shops, hotels and entertainment, may presage future acquisitions.

Real Estate Replay

Given the rapid entry of Chinese investors into developed markets, it is easy to draw parallels between ongoing trends in outbound Chinese investment with similar purchases made by Japanese investors decades earlier. Throughout the 1980s, Japanese investors bought skyscrapers, golf courses and hotels as they sought reliable returns for their considerable foreign exchange reserves.

In 1988, Japanese investors’ spending on US properties reached its peak at $16.54 billion (equivalent to $31.5 billion in today’s money), prompting fears of a “Japanese takeover”. Investors were quickly brought down to earth, however, when the bursting of an asset bubble stalled a Japanese economy that had enjoyed decades of rapid economic growth, ultimately leading to the offloading of some of the most prestigious real estate, including the Rockefeller Center in New York, and often with heavy losses.

The impressive list of recent Chinese acquisitions coupled with a surge of wealthy mainland individuals buying up properties throughout mature markets are prompting similar worries of a “Chinese takeover”. In reality, Chinese investors are just one slice of international investors pouring capital into global hubs such as Los Angeles, New York and London. A research report by CBRE reveals that investors from the United States, Canada and Germany were in fact the top three sources of cross-border investments in commercial real estate for the first half of 2015.

China only ranked fourth in that list, but ongoing regulatory reforms, coupled with mainland firms’ growing confidence and experience, will likely contribute to further outbound investment in commercial real estate. Continued stock market uncertainties and currency devaluations will also increase Chinese desires for the relative safety of real estate in developed markets. “We know that the extent of Chinese available capital tends to be huge. At the moment, only a small part of those reserves have been deployed. The growth potential is enormous,” says Ji.

Potential investors are also monitoring the regulatory environment in foreign countries. In December 2015, President Obama signed a new bill into law that eliminates taxes on foreign pension funds seeking to invest US real estate. While fears of a Chinese “invasion” could prompt a backlash, such as the one that derailed Huawei’s attempted acquisitions of US technology firms, for the moment, regulations on the mainland and overseas are relatively relaxed.

The Waldorf Astoria stands as a towering symbol of Chinese investors’ growing clout in commercial real estate markets. And despite the presidential snub, the downtown Manhattan hotel will continue to attract wealthy clientele and substantial income. No investment is ever certain, but, for now, the relative safety offered by tangible assets presents an attractive alternative for Chinese investors wary of unstable stock markets and currency devaluations.