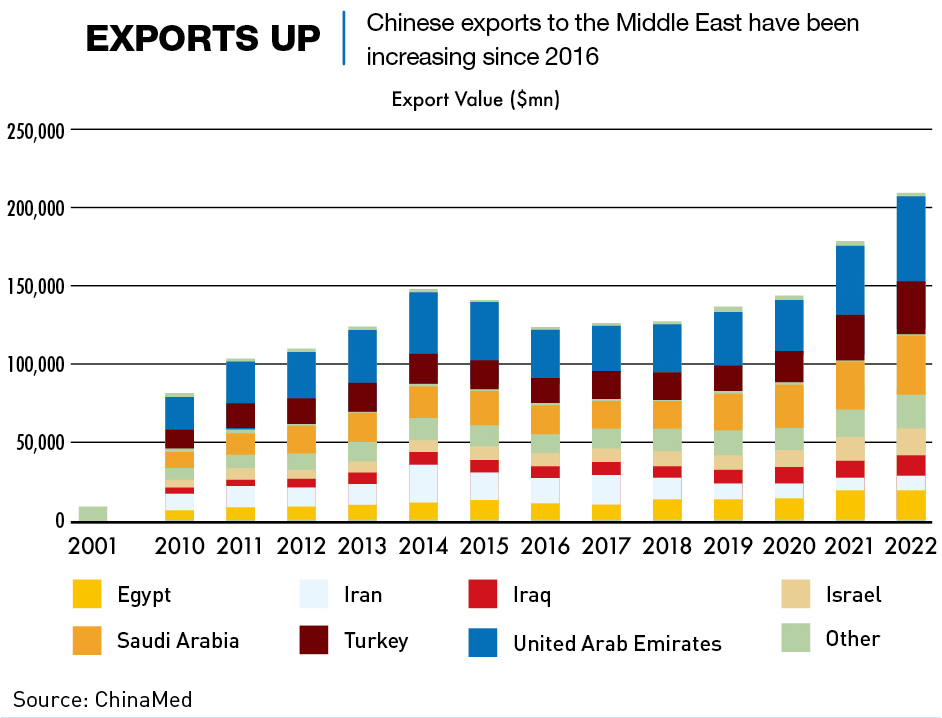

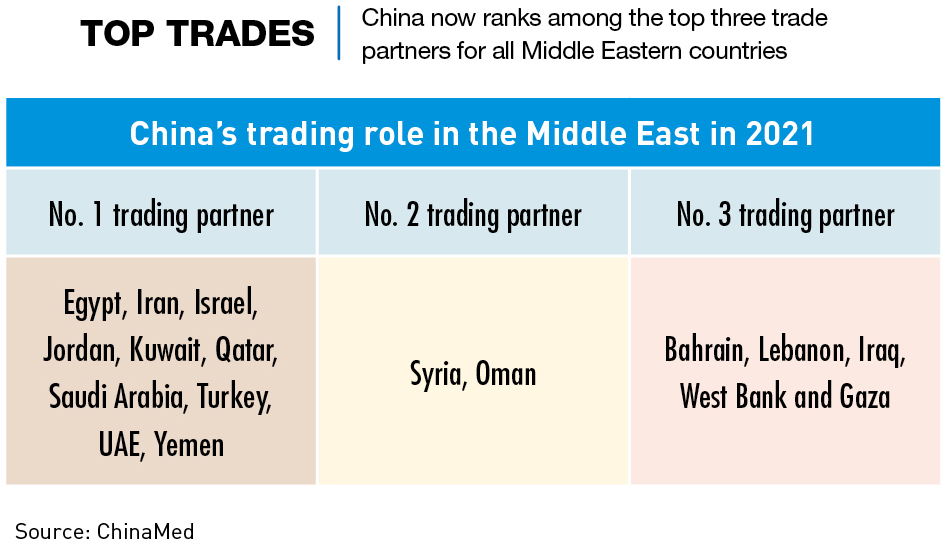

China is now the main trading partner of almost all Middle Eastern countries, exemplifying the growing relationship

The number of foreign embassies in the diplomatic quarter of Riyadh increased by one in June 2023, when Iran reopened its embassy after resuming its diplomatic mission to Saudi Arabia after seven years. The surprise détente between the regional rivals stunned the world—all the more because it was China that brokered the rapprochement.

The breakthrough mediated by the Middle Kingdom followed years of attempts by other Muslim countries, and a triumphant Beijing could barely contain its delight at having outmaneuvered the US.

The renewed relations were perhaps less of a Chinese coup than it appeared at first glance, as Riyadh and Tehran had their own reasons to defuse tensions, but the rare direct intervention nevertheless provided an important win for China as its first credible piece of diplomacy in the Middle East.

The success highlights China’s growing clout in the region despite longstanding US dominance. Economic engagement is also on the rise—China is already the biggest trading partner for most of the countries in the Middle East and now suddenly the largest investor amid waning investment and growing hostility from the US and EU.

“The countries of the Arab Gulf—Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in particular—are very important partners for China not only in energy but also in technological cooperation,” says Dawn Murphy, author of China’s Rise in the Global South: The Middle East, Africa and Beijing’s Alternative World Order. “And China’s economic approach to the region is very complementary to the vision that the Gulf states have for their longer-term economic development.”

East meets East

Well before the Saudi Arabia-Iran deal, China had already established itself as a vital partner to the oil-rich Gulf theocracies and monarchies. The country is the biggest buyer of oil from Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq and the UAE, and Beijing has further cemented these relationships in recent years with comprehensive strategic partnership agreements.

With the exception of Iraq, these countries, along with Qatar and Kuwait, are also members or observers of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a political, economic and security forum founded by China, Russia and four other countries.

China’s relationship with the region extends beyond just energy, due in large part to its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched a decade ago aimed at better connecting Asia, Europe and Africa through a China-backed network of ports, railways, highways and other infrastructure projects.

“The BRI has been the catalyst for enhanced connectivity, facilitating infrastructure development and trade linkages,” says Gan Mei, director of China business development at PwC Middle East. “The Middle East’s strategic geographic location has positioned it as a vital hub within the BRI framework, further boosting trade between China and the region.”

Beijing built the $1.8 billion metro system in Mecca and is helping Egypt build its new lavish capital outside Cairo, although there are doubts over the latter’s commercial potential. “Egypt is in deep crisis and many would argue that throwing money into Egypt is like throwing money into a black hole,” says James Dorsey, a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute of the National University of Singapore.

“For China, what’s attractive about the Middle East is that on one hand, there is the longstanding energy trade, and then on the other, the regional markets for Chinese goods and services are just as important as resources,” says Murphy.

Bilateral trade between China and the Middle East nearly doubled in the five years from 2017 to 2022, from $262.5 billion to $507.15 billion. It grew by a record high of 35.7% last year, significantly faster than that of China’s top three trading partners, namely ASEAN on 15%, the EU on 5.6% and the US on 3.7%. By comparison, US trade with the Middle East and North Africa increased much more modestly over a longer time span, from $63.4 billion in 2000 to $98.4 billion in 2021.

But China’s outbound foreign direct investment (OFDI) in the Middle East is considerably smaller, reaching just $2.397 billion in 2019, and accounting for just 1.75% of China’s total OFDI flow in 2019. That year, only the UAE ranked among the top 20 destination countries. But in 2022, China’s direct investment in Arab states jumped by $2.62 billion or 13% year-on-year, while Arab states increased investment in China by $1.05 billion, a near ninefold year-on-year rise.

In December 2022, Chinese leader Xi Jinping visited Saudi Arabia for three days, during which he also held Beijing’s first-ever summits with the Arab League and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman described the visit as marking “a new historical era” in ties between China and his country.

Economic and trade cooperation have expanded in recent years to new frontiers such as aviation, aerospace and the digital economy, and fostered new growth resources such as green and low-carbon development, health and medical services, and investment and finance. For example, China’s rapid advances in cutting-edge tech in recent years mean that Beijing can offer access to services like 5G connectivity through companies such as Huawei.

This aligns with Middle Eastern efforts to emphasize non-oil sectors such as renewable energy, clean technology, tourism and infrastructure, all of which provide China with a potential role. Saudi Arabia last year set a goal to boost the share of non-oil exports in non-oil GDP from 16% to 50% by 2030, while the non-oil sector already contributes more than 70% of the UAE’s GDP.

“Several Gulf countries have relatively advanced economies in areas ripe for technological cooperation with China, such as artificial intelligence (AI), green technology and biotechnology,” says Murphy. “There are many areas where China, given its desire to also advance in those particular sectors, finds cooperation with those countries to be particularly productive.”

Saudi’s eagerness to diversify reaped dividends in 2023 when $10 billion worth of investment deals were inked during a two-day Arab-China business conference held in Riyadh. Amongst the most notable was a $5.6 billion agreement between Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Investment and Chinese electric vehicle (EV) manufacturer Human Horizons Group to jointly develop cars.

Still, energy is expected to remain the main source of business between China and the Middle East for many years to come. In 2022, China imported 270 million metric tons of crude oil from the Middle East, representing 53.13% of total imports, while inflows of liquefied natural gas (LNG) topped 17.23 million metric tons or 27.1% of total volumes. Chinese demand for Middle Eastern fossil fuels shows no signs of slowing down either, as state-owned oil company Sinopec signed a massive deal in November 2023 for further supplies of LNG from gas-rich Qatar until the early 2050s.

A new balance of power

China’s expanding economic footprint is butting up against longstanding US influence in the region, making the Middle East the latest battleground between the two superpowers. Last year, both Joe Biden and Xi Jinping visited Saudi Arabia and the surrounding region, but it is no secret that the current US administration and regional lynchpin Saudi Arabia do not see eye-to-eye. More broadly, Washington’s staunch and unconditional support of Israel and unswerving animosity toward Iran have rankled Arab leaders.

“It certainly helps Beijing that China is perceived with less historical baggage than the US,” says Benjamin Ho, author of China’s Political Worldview and Chinese Exceptionalism and an assistant professor at the China Programme at Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. “Countries in the Middle East are also happy to keep the more contested issues outside the relationship in favor of a more transactional approach. The Middle East doesn’t interfere in what is happening in China, and China doesn’t interfere in what’s happening in the Middle East.”

The dynamics are providing an opportunity for China—historically not involved significantly in the Middle East’s affairs—to grow its influence. Trade and investment partnerships in recent years have elevated ties between China and Saudi Arabia, Iran and Djibouti. The latter also hosts China’s first overseas military base not far from the Bab al-Mandab Strait, a narrow waterway that is a critical artery for transporting goods between Europe and Asia.

Relations with Israel—a stalwart ally of the US in the Middle East—had also been on a steady upward trajectory since 2017, when Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu met Xi for the second time during a state visit that included the establishment of a China-Israel innovative comprehensive partnership. A second trip to Beijing by Netanyahu was scheduled for October 2023, but scotched by the outbreak of war in Gaza the same month. China’s response to the conflict between Israel and Hamas has been cautious and diplomatic, and a historic pro-Palestinian stance and a refusal to condemn Hamas for its terrorist attack has not endeared Beijing to Tel Aviv.

“China’s relationship with Israel right now is pretty tricky but I don’t think the Chinese are worried about that too much unless the Hamas war ends up becoming long-drawn-out,” says Ho.

China has looked to develop its regional presence in areas beyond business and trade. There has been security cooperation between Washington and Beijing in the Middle East, in the form of China’s participation in anti-piracy efforts off the coast of Somalia in the Gulf of Aden. And diplomatic overtures led to an Arab-centric expansion of the China-dominated BRICS group in 2024, with the addition of Saudi Arabia, Iran, Egypt and the UAE.

Growing economic stakes

China’s investments have increased in the Middle East in recent years, mostly centering on ports and infrastructure that have strategic value for ensuring safe passage of Chinese goods to Africa and Europe. Much of this has been channeled through the BRI, understandable given China’s dependency on energy imports from the region.

“There are a broad range of sectors capturing Chinese interest but a definite standout is infrastructure development,” says Murphy. Middle Eastern countries received $8.1 billion of investment and construction contracts from China in the first half of 2023, representing about 19% of the total for the six months, although it was down considerably from $12.3 billion a year earlier.

Chinese money is behind some of the Arab world’s biggest projects under development. These include the Red Sea Gateway Terminal, a joint venture between China’s COSCO Shipping Ports Ltd. and Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund to develop and operate a container terminal at Jeddah Islamic Port. Egypt—strategically located at the crossroads of the Middle East, East Mediterranean and Africa—has been a focal point too, as Chinese investment in Egypt rocketed by 317% from 2017 to 2022, while American investment during the same period slumped by 31%.

Iraq was the top recipient of China’s BRI financing for infrastructure projects in 2021, with about $10.5 billion in construction contracts. China further sought to invest $10 billion in infrastructure projects in the Autonomous Kurdistan Region in northern Iraq.

Additionally, China was set to help reconstruct war-torn Syria. While Russia remains the dominant foreign power in Damascus, Moscow cannot compete with Chinese companies’ impressive infrastructure record. But Chinese assistance in rebuilding Syria has not yet materialized since Bashar al-Assad declared victory in the Syrian civil war in 2018, casting doubt over Beijing’s willingness to help.

“The Chinese really have not had much more than a trade transactional relationship with Syria,” says Dorsey. “They may well be interested in ports but the Russians have a grip on that because of the military intervention in Syria.”

A China-Syria strategic partnership was announced in October 2023, which will include Syrian participation in the BRI, but what will result from it is not yet clear.

Outside of megaprojects, Beijing also has big plans to extend its digital footprint to the region. The Middle East plays a prominent role in China’s Digital Silk Road (DSR), under which Chinese companies have secured 5G deals with the GCC countries. Tech linkages between China and Saudi Arabia and the UAE have blossomed in particular—both countries have signed DSR memoranda with Beijing and are cooperating on telecommunications networks, AI capabilities, cloud computing, e-commerce and mobile payment systems, surveillance technology, smart cities and other high-tech areas.

“While China seeks to expand its role as a high-tech power and use data as a tool to promote economic transformation and development, Middle Eastern countries are increasingly looking to digitize and diversify their economies,” says Murphy. Within its digital cooperation with the Middle East, China has become a prominent player engaging in joint research, technology transfers and knowledge sharing, Murphy adds.

But Washington is only willing to let this burgeoning cooperation develop so far. “You’re starting to see the limitations because on issues like technology and military cooperation, the boundaries are being set,” says Dorsey. As an example, he cites G42, a leading AI company in the UAE, with a Chinese CEO, that said late last year it would cut ties with Chinese firms under pressure from the US. “It was forced to choose between access to US technology and dealing with China. That was a balancing act it was no longer capable of doing,” says Dorsey.

Business beyond petroleum

Finance and capital markets are also emerging as promising points of cooperation. Saudi Arabia’s first exchange-traded fund in Asia successfully debuted on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEX) at the end of November 2023, offering investors exposure to the Kingdom’s $1 trillion economy and world’s biggest oil company, Saudi Aramco. The debut came after the HKEX and the Saudi stock exchange signed a memorandum of understanding to explore cooperation in areas including fintech, cross listings and ESG.

There has been “substantial collaboration growth” in finance, agrees PwC’s Gan. “Mutual investments, currency swap agreements—like the one worth $7 billion signed between China and Saudi Arabia in November 2023—and the establishment of financial hubs have further solidified economic ties, providing a foundation for enhanced economic cooperation and stability,” says Gan.

China has stepped up efforts to court Middle East money, and investment is blooming, with Middle Eastern wealth capital topping up the funding of Chinese venture capital firms, and Arabian sovereign wealth funds (SWFs)—which together had more than $4 trillion of assets under management at the end of November 2023—are eyeing stakes in Chinese businesses. In June 2023, the head of the HKEX predicted that the China allocation of Middle East’s biggest SWFs, expected to reach $10 trillion of investment capital by the end of this decade, would expand to 10-20% compared with just 1-2% now.

In recent years, Middle Eastern countries have also pumped billions of dollars into Chinese industry leaders. Near the end of 2022, Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, one of the world’s biggest SWFs, became a top-10 shareholder in China’s biggest coal company Shenhua Energy and its top gold and copper miner, Zijin Mining.

More deals followed in 2023. In June, the investment arm of the Abu Dhabi government paid $738.5 million for a 7% share of Chinese EV maker Nio, while Riyadh clinched the $5.6 billion deal with Human Horizons. Energy ties deepened the following month when Aramco completed a blockbuster ¥24.6 billion ($3.45 billion) acquisition of a 10% stake in Shenzhen-listed Rongsheng Petrochemical, which controls China’s largest integrated refining and chemicals complex.

As Arab wealth flows into new areas of fruitful cooperation with China, it has been withdrawing from others that are struggling. “Real estate, including commercial and residential, used to be an area that attracted significant Middle Eastern investments,” says Gan. “However, we have noticed that the new investments in this sector have slowed down, especially during and post-COVID-19.”

But, energy, primarily oil, remains the key to the relationship between China and the Gulf. Of the $89.4 billion of bilateral trade between China and Saudi Arabia in the first 10 months of 2023, $45.56 billion or just over half was taken by Chinese imports of Saudi oil, according to customs data. It is a similar story with the UAE, as crude oil and LNG imports made up 29% of $77.7 billion in two-way trade with China over the same period. And with Qatar, energy exports comprised 68% of total trade of $20.4 billion. The recent slew of oil and gas deals means energy trade will only grow.

“It’s an interesting dynamic because China is moving to alternative energy sources within its own borders and at the same time, through its cooperation with the Arab world, promoting a lot of green technology,” says Murphy. “But there is a tension in that China is currently vulnerable in being so dependent on energy imports, and these countries being much too dependent on one particular resource in their broader economic portfolio. I think that’s part of why China is attractive to them and why they’re attractive to China.”

Both sides are laying the groundwork for a future when China is less dependent on foreign oil and gas, and Middle Eastern states have diversified their economies away from exports of hydrocarbons. “This is why they focus much more on the other aspects of economic engagement, and having them as a foundation of relations going forward,” says Murphy.

Cautious optimism

Israel’s war against Hamas in Gaza and Houthi rebel attacks against shipping in the Red Sea are amongst the factors that could hold back greater Chinese investment in the Middle East. “Potential impediments might include geopolitical uncertainties and evolving global economic dynamics,” says Gan. “Regulatory updates and cultural differences may also act as hurdles.”

Still, there is an economic complementarity in China-Middle Eastern relations that suggests Beijing’s regional clout will continue to grow, offsetting growing discord between China and the West. “If there is a rupture in relations between Beijing and Washington and/or Brussels, the Middle East and the Global South more broadly becomes much more important to China in the longer term, as a source of resources, markets and broader engagement,” says Murphy.

While business ties are booming, Beijing will still want to tread cautiously in a region notorious for its complexity and high levels of tension and conflict. “The Middle East has never been an area where any kind of long-term engagement is possible,” says Ho. “Its history of conflicts predates Chinese civilization depending on how far you want to look back.”

“China is not going in with any kind of rose-tinted glasses,” he adds. “For them, it’s better to just go in for whatever interests are desirable, never think they will be permanent, and always be prepared to leave the region.”