There are a number of reform options available to help China deal with its economic headwinds

Predictions about China’s economy and its trajectory have polarized observers in recent years even at the best of times, but a rare moment of near unanimity occurred late in 2023 when leading global institutions and prominent forecasters took turns to downgrade their growth outlook for the world’s second-largest economy.

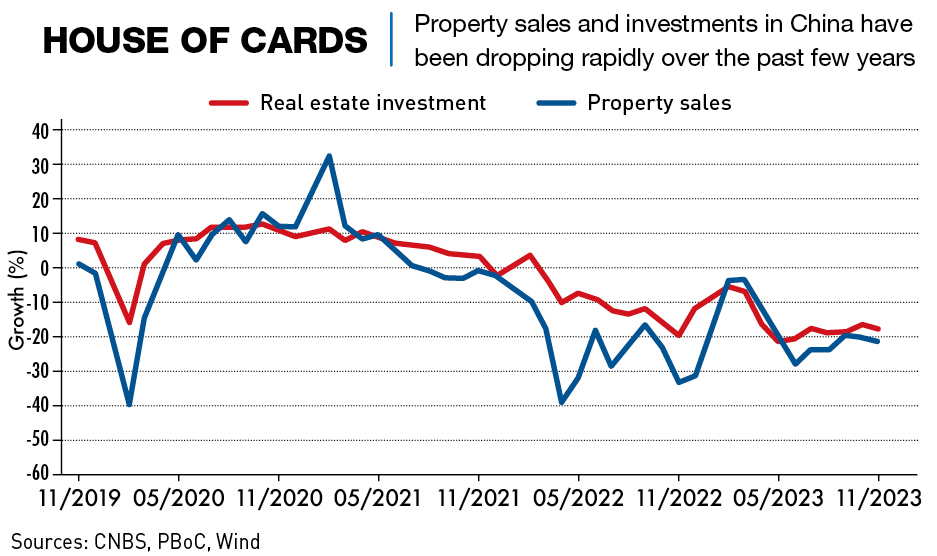

At its annual meeting in early October, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) said it expected China to grow by 5% in 2023 and 4.2% in 2024—less than previously predicted—due to a moribund real estate market and weak external demand. The cuts came after two out of the ‘Big Three’ credit ratings agencies, Fitch and S&P Global, also lowered their growth expectations. The third agency, Moody’s, maintained its projection for 2023 but slashed its 2024 prediction the sharpest out of the trio.

Less than a month after its downbeat outlook for China, the IMF upped both estimates by 0.4%, reflecting improved prospects after an upbeat Q3, and there are still some players, including some Wall Street banks and China forecasters that are more positive. It is also important to remember that reported growth of 5% would be considered solid in any other economy. But there is clearly an unusually high level of uncertainty in China’s economy, which enjoyed fast and virtually uninterrupted growth for the past 40 years.

China’s economy is still searching for more stable footing, and prospects for 2024 and beyond are darkening. Lackluster growth driven by a deep and sustained real estate slump has led to renewed calls for reforms to address long-standing imbalances and unleash new growth drivers. But there are a number of different ways to go about reshaping a country’s economy and experts are divided on how China should approach its problems.

“China’s current growth headwinds are underpinned by deep-rooted structural imbalances that need to be addressed for its economy to successfully transition to a more sustainable, demand-driven growth model,” says Alfredo Montufar-Helu, head of the China Center at global think tank, The Conference Board. “Without doing this, there is a real risk that China could fall into the middle-income trap—like what happened in Latin America.”

The Middling Kingdom

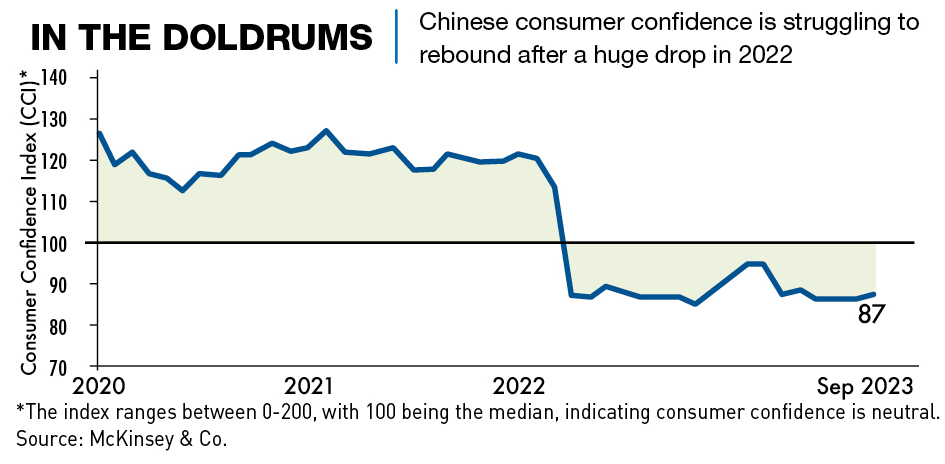

The challenges stressing China’s economy are numerous and formidable, ranging from a sluggish property market and trillions of yuan in local government debt, high urban youth unemployment, weak consumer confidence and spending, declining appeal for foreign investors and rising trade protectionism. And China has little time to waste.

“We actually project that without structural reforms, medium-term growth in China could fall below 4%,” IMF managing director Kristalina Georgieva said in September 2023, urging Beijing to shift toward a consumption-based growth model.

While the list of obstacles is daunting, China has proved resilient, having weathered the Asian Financial Crisis, the Global Financial Crisis, the one-off yuan devaluation shock in 2015, and the initial COVID outbreak nearly four years ago.

“The key difference this time is there are no reforms that are relatively easy to implement to act as growth drivers,” says Linda Glawe, author of The Economic Rise of East Asia. “Innovation-based growth is more difficult to achieve.”

While Beijing has managed to adroitly sidestep shocks to the system in the past, it is in uncharted territory this time as there is no precedent for an economy of China’s size and governance system facing so many headwinds simultaneously.

The country’s economy is highly centrally controlled, which is an enormous advantage in the good times but poses a problem when the economy is struggling. Economists also point to China’s history of cycling through centralization when control is tightened, and decentralization when an easing-off enables reforms. Chinese society and politics have arguably been in a lengthy cycle of tightening since an important party meeting in 2013, which pledged significant market reforms, most of which have not been implemented.

“What we’ve seen since then is not only that control and power have actually been further centralized within the Party,” says Montufar-Helu. “There are many reasons why this transpired, but it tells us that reforms will be implemented on China’s own time and in line with China’s own development priorities, and a Western-style market economy is not one of them.”

Reasons for cheer

The longer-term challenges do not mean it is all doom and gloom for the Chinese economy as Beijing has managed to cultivate several new growth points. For instance, China leads the West when it comes to many clean energy technologies, and Chinese automakers have taken pole position in the fast-growing global electric vehicle (EV) industry.

China’s current EV leadership complements its stranglehold over technologies critical for the energy transition such as solar photovoltaics, wind turbines and batteries for EVs and energy storage—a grouping known as the ‘new three’ that has become a market buzzword.

The world’s biggest clean energy producer and consumer already controls 80% of the global solar market, occupies 60% of the market for wind turbines, and produces three-quarters of all lithium-ion batteries. And with China’s installed solar and wind capacity on track to reach 1,200 GW by 2025—five years ahead of schedule—the country will continue to be a clean energy superpower with a manufacturing base that underpins renewables rollout in the rest of the world.

Other bright points that will help China overcome its issues include digitalization and artificial intelligence (AI) deployment. Greater AI implementation in industries ranging from automotive, transportation and logistics, to manufacturing, enterprise software, healthcare and life sciences could create $600 billion of new economic value annually in China, according to McKinsey.

“A combination of automation, digitalization and AI is not a panacea to solve all of China’s problems, but it could be a good step in the direction of an innovation-based growth strategy,” says Glawe. “If China could then solve its other structural problems one by one, I would be quite optimistic in the long run.”

But Chinese dominance in future-facing industries has also put it in the crosshairs of other governments. Following an influx of cheap Chinese EVs into Europe this year, the European Commission (EC) is formally investigating imports of EVs made in China to check if they benefited from unfair state subsidies. The probe, which China’s Commerce Ministry has opposed, could lead to tariffs to protect European automakers against cheaper imports. The EC also plans to scrutinize subsidies for foreign wind turbines, which would similarly ensnare Chinese models.

And while Beijing has touted the performance of new growth drivers, it is unlikely that they will be enough to replace the ‘old three’ growth drivers of property, infrastructure and manufacturing that propelled China’s economic rise.

Reforms to the rescue

Reforms could be the antidote to securing the high-quality development that Beijing craves, and while the recovery could be bumpy, it could also provide opportunities for further reducing financial risks, strengthening the social safety net and implementing market reforms to encourage private investment—all of which could address long-standing structural changes.

1. Tax

An overhaul to China’s tax and fiscal system so it is more reflective of a modern major economy is much-needed and could be achieved via a carbon tax, property tax or broader application of personal income tax. Tax revenue equaled 21% of China’s GDP in 2021, compared with about 27% in the US, and less than 10% of China’s population pays any income tax at all.

“The necessity [for fiscal system] is self-evident,” says He Wei, China economist at Gavekal Dragonomics. “The local government funding situation is not looking good and land sales are unsustainable, so China needs to find other sources to plug the hole.”

The financing problems affecting the real estate market and local governments are interrelated and stem from “a structurally misaligned fiscal system that not only failed to generate adequate revenue, but also does not match the revenue needed with the expenditure responsibilities of local governments,” according to Michael Pettis, professor of finance at Guanghua School of Management at Peking University and a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “The central government gets most of the fiscal revenue, but local governments are burdened with the bulk of the expenditure responsibilities.”

This means any expansion of the tax base to boost revenue for local governments would need to be paired with a rethink of their general economic functions.

2. Finance

Another possibility is the reform of China’s financial sector, worth ¥449.21 trillion at the end of June 2023. Domestic banks, almost all state-owned, can currently count upon a huge cushion of savings that included ¥135 trillion of personal deposits at the end of September 2023, but if China wants to rebalance toward consumption-led growth, this buffer will have to decline. Lowering total savings first requires improved asset allocation choices.

There are several options for deeper reform of China’s financial sector, including a diversification of the bank-dominated system and the de-linking of local governments and local banks.

3. Employment

China’s decades-old policy that lets women in some jobs retire as early as 50 and men at 60, is also ripe for change. Raising retirement ages would temporarily reverse a contraction in the working-age population, which has declined annually to 875.56 million in 2022, since peaking in 2011.

The State Council said in February 2022 that China would “implement a gradual extension” of the retirement age by the end of 2025, but authorities have yet to announce any formal adjustments. Although it would be deeply unpopular, Wang Yong, academic deputy dean of the Institute of New Structural Economics at Peking University, believes a hike could be the most immediately consequential reform that Beijing could implement.

“This is not just one option, but the only option,” he says. “China is aging and the official retirement ages are absurdly low. It is imperative to increase them—it’s just like the one-child policy, which should have been abolished much earlier, but was not done until it was too late.”

Another proposed reform that has been front and center in recent years is the relaxation of China’s hukou system, a household registry that makes it difficult for rural residents to obtain social benefits in cities, thereby preventing them from moving permanently. Equalizing urban benefits could transform the lives of up to 180 million migrants, enabling them to access basic services and social welfare tied to their hukou.

The idea has considerable backing in Beijing—former People’s Bank of China (PBOC) governor Yi Gang said in September 2023 that hukou reform should be advanced as research has shown it could boost consumption among migrant workers and new arrivals by 23%.

4. Welfare

Shrinking the divide between haves and have-nots in Chinese society would encompass welfare reform too. China’s current social safety net favors urban white-collar workers. Only around one-third of the working population was covered by their employers for unemployment insurance at the end of September 2023.

Behind China’s massive household savings is the overall cautious attitude toward spending, which also has a big impact on consumption.

“If China really wants to have a sustainable recovery in consumption, it needs to reduce its population’s need for precautionary savings,” says Montufar-Helu. “But in order for this to happen, governments have to provide a structure that gives people confidence. For example, a strong social security net and robust pension system, which China does not have. Neither does it have equal access to high-quality healthcare and education services across all of the country. But they are all essential to increasing confidence.”

5. SOEs

China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs)—which included 27 out of the world’s 100 biggest companies by revenue in 2022—have undergone a series of progressive reforms since the 1970s aimed at remaking them into more modern corporations. The SOEs are a critical part of China’s economy and there is broad agreement that they perform poorly overall.

“In the past SOEs were encouraged to expand, their size mattered,” says He. “More recently, there has been more emphasis on profitability. But SOEs exist in China for a reason—they’re not purely market-driven institutions rather they need to contribute positively to society, so there is a certain limit on how far SOE reforms can go.”

6. Private Sector

China’s economic malaise this year has highlighted the importance of the private sector, which contributes over 50% of tax revenue, 60% of GDP and 70% of technological innovation achievements.

Low confidence levels among cautious entrepreneurs and private business owners, coupled with skepticism of Beijing’s friendliness toward the private sector, spurred the State Council to issue a 31-point plan in July 2023 to revitalize the private sector, pledging to build a “bigger, better and stronger” private economy.

More support to shore up confidence came in September 2023 when Beijing published a list of public-sector projects targeted at private businesses and the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) received official approval to form a new bureau to monitor and advocate for the private economy, a development that one expert described as “groundbreaking” because it is the first national-level body dedicated to private business.

But there appears to be a limit on how much Beijing is willing to talk up the private sector—an article in August by PBOC adviser Liu Shijin that called for private sector reform and for leaders to “make it clear politically” that entrepreneurs are the “precious resource of the socialist economy” was deleted from social media.

Walking the talk

Broad-based and pro-market structural reforms could help boost productivity, facilitate rebalancing and ignite new growth drivers, according to the IMF—but even getting them started won’t be easy. Each of the aforementioned reforms carries considerable structural risk, and cuts into the interest of groups in society that have managed to block these reforms thus far—including some parts of the system, but also urban citizens and the relatively well-off.

A long-discussed property tax and broader application of the personal income tax system would help local governments make up some of the lost revenue from muted land sales, but would also deal a blow to already weak business and consumer confidence. In China—long home to the conviction that property is the most reliable store of wealth—homeowners would almost certainly balk at any attempt to tax their properties, despite Beijing’s completion of a unified, national property registration system in 2023.

“A property tax is basically off the table for the next five years,” predicts Gavekal’s He. “There’s no strong reason why they would implement one now, especially given current growth is quite sluggish. If you want to increase local government revenues, you either have to increase taxes or get a bigger slice of existing tax revenue from the central government. I don’t see either happening.”

But Beijing did make sweeping regulatory changes to the financial sector in mid-March 2023, essentially bringing the financial regulatory system under tighter, centralized control.

Among the biggest changes were the establishment of the National Financial Regulatory Administration (NFRA) and the abolishment of the PBOC’s nine regional branches, to be replaced by 36 branches across the country. The two changes indicate a shift to an empowered, centrally-controlled architecture that should help Beijing address some of the risks surrounding small lenders that have been plagued by poor governance, fraud and weak balance sheets.

“You can’t let small banks default because if they go under, it’s ultimately the depositors who pay for it,” says Pettis. “No government today, in China, the US, Europe or elsewhere, would allow its banks to default on its depositors. You don’t resolve the problem by cutting the banks free until they’re cleaned up and recapitalized.”

Social security reforms have also been progressing, though often piecemeal. Several cities including Shanghai and the provincial capitals of Hangzhou and Zhengzhou have relaxed stringent hukou policies for certain groups of society, while the Ministry of Public Security announced in early August 2023 that it would promote the nationwide implementation of reforms to the hukou household registration program that were originally outlined in 2021.

“Hukou reform is a classic example of what China needs to do and why it’s difficult,” says Pettis. “If the hukou was eliminated overnight, the working population would shift to the better cities and that creates a problem because those cities would have to either cut back on services to all residents to be more egalitarian or significantly improve services for those who previously weren’t treated as well. You run into the same problem—how will it be funded?”

Many of the changes such as delaying the retirement age are sensitive and carry economic trade-offs. For instance, retirees often provide childcare for their grandchildren, but putting off retirement would upend this arrangement.

Besides the inherent difficulties of some reforms, there are also many systemic barriers. Powerful institutional or business interest groups populate the party-state and have acted as a roadblock to reforms in the past as they have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo—the late premier Le Keqiang once memorably said: “shaking up vested interests could be more difficult than touching the depths of souls.”

For instance, China’s national oil companies wielded considerable political sway up until the early 2010s, enabling them to influence national policies and projects in the energy sector and beyond until a major anti-corruption campaign a decade ago reined in their power.

The scale of the issues that the reforms aim to overcome is also vast due to the size and complexity of China’s economy, and the interconnections of the system are such that changes in one corner can upset other areas, according to He.

“China has to prioritize,” says Glawe. “There simply isn’t enough money to reform everything at once.”

The biggest test yet

Often overlooked in trite descriptions of China as a monolithic authoritarian country is that it is home to a vibrant economy with a storied history of reform—from state-led production under the planned economy to Deng Xiaoping’s open-door policy 40 years ago, to investment-boosting manufacturing and innovation in the past two decades.

Implementing solutions to the present imbalances and structural drags will be tougher than anything Beijing has previously overcome, as it will involve painful changes that may not pan out for years to come.

What’s past is prologue, as the saying goes. But China’s capacity to muddle through should not be underestimated.

“No matter whether in 2013 or 2023, the most important challenge China faces remains the same: growing the economy and increasing the living standard of Chinese people,” says Wang. “History has already proved that following the market mechanism is the only way to achieve sustainable economic development.”