China’s OFDI into the Global South has been focused mainly on infrastructure projects and resource aquisition

In 2022, a subsidiary of Chinese battery giant CATL signed an agreement that secured it long-term access to one of the world’s largest nickel reserves. The Indonesia EV Battery Integration project that resulted, worth almost $6 billion, is emblematic of an increase in Chinese companies turning to the Global South to secure key resources, as part of a shift in outbound investment.

Overall Chinese outbound foreign direct investment (OFDI) is down around 30% from its peak in 2016, both due to domestic regulatory changes and growing geopolitical tensions. But with China’s strict zero-COVID policy now behind it, the world’s second-largest economy is returning to global investment, albeit with different targets in mind.

After China’s accession to the WTO in 2001, Chinese OFDI was largely targeted towards the US and Europe, but that has declined dramatically, and while increased investment in the Global South has so far only made up some of the difference, it appears to be the future direction for Chinese OFDI.

From solar panel plants in Southeast Asia to mining projects in Latin America as well as a plethora of deals in Africa and the Middle East, Chinese investors, driven in part by the Belt & Road Initiative (BRI), are securing critical resources, broader market access and technology portfolios in an ever-changing global landscape.

“While China has continued to focus on securing resources, there have been a number of changes taking place,” says Richard Bolwijn, Officer in Charge at the UNCTAD Investment and Enterprise Division. “There has been a shift in the modalities of how the investments are being made, an increase in infrastructure investment and a shift in geographical targets.”

A new stage

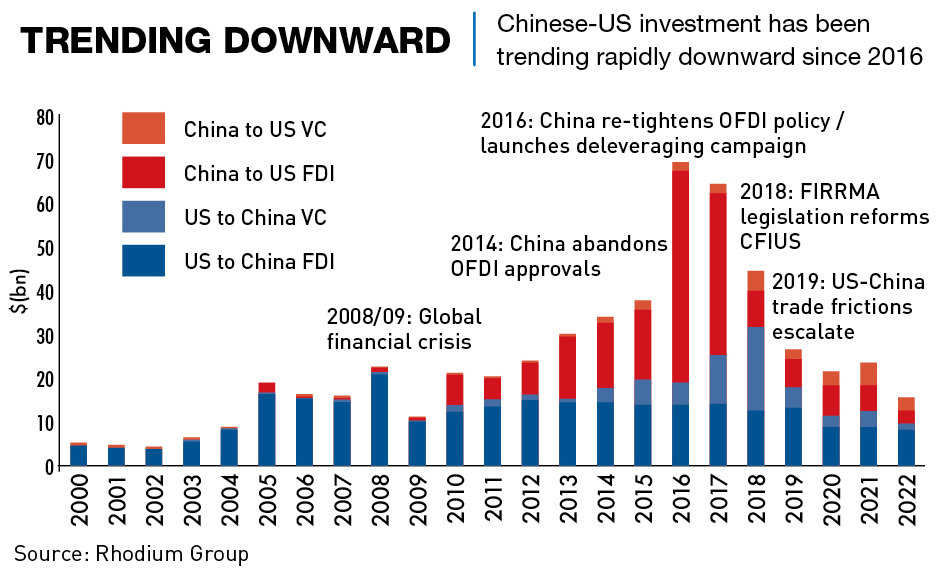

The total amount of Chinese OFDI varies quite significantly, depending on which numbers you consult. The Chinese Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) statistics tend to be on the higher end of estimates, while others, such as the American Enterprise Institute, have reported numbers that are as little as one-third of MOFCOM estimates. But while the statistics vary, the trend of lower OFDI since 2016 is consistent.

Chinese overseas investment mostly began in the 1990s with state-owned enterprises (SOEs) buying natural resources that were in great demand in China, such as oil, timber and ores, in order to help control pricing and supply. As private enterprises boomed through the 1990s and spurred on by the introduction of China’s ‘Going Global’ strategy in 1999 and the country’s accession to the WTO in 2001, they too started looking for acquisitions outside of China, with goals directly related to their own individual business needs.

Then came the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008, which the Chinese government saw as an opportunity for both “China Inc.,” and the country’s private enterprises, to buy up a wide range of assets in the West, including manufacturing and energy, at cheap prices. Outbound investment grew dramatically after the GFC, with Beijing further loosening investment restrictions in 2014, making approvals for the export of funds to cover the purchase of assets around the world relatively easy to obtain.

But this more laissez-faire approach was short-lived, and with the advent of China’s own, smaller, financial crisis in 2015—with some estimates putting the amount of money leaving the country at more than $1 trillion per year adding pressure to the RMB exchange rate—the approval process became much tougher.

Wary of capital flight risk and the high leverage levels of many of the conglomerates doing the investing, and a high number of trophy asset acquisitions, the Chinese government adjusted its policy to a more cautionary stance after 2016 by tightening capital controls and stepping up supervision on companies’ deal-making. Thanks to these policies, and a growing regulatory scrutiny abroad towards foreign investments in certain countries and sectors, Chinese OFDI fell to a low of $136.9 billion in 2019.

Prior to this, investments during this growth phase were targeted at the US and in particular the technology, real estate and entertainment sectors. According to a Rhodium Group analysis, the US alone was the recipient of $46 billion in Chinese investments in 2016—the year China’s OFDI peaked at $200 billion.

Europe was also a target for Chinese investment, with an initial focus on Germany, France and the UK, but a growing spread among other countries on the continent. But again, investment into Europe peaked in 2016 at €37.3 billion ($40.21 billion). China’s outbound investment in Europe (EU27+UK) hit a decade low of €7.9 billion ($8.8 billion) in 2022, according to a Rhodium Group report, and the numbers released by China’s MOFCOM also show the lowest investment levels since 2016. And thus began a decline of investment in major Western economies.

“The decline in investment in the US and Europe was as much because of intervention from Chinese politics as it was Western politics,” says Bolwijn. “Early on there was a push by the Chinese government to reduce outward investment when foreign exchange reserves started to dwindle. And today we see more reluctance on the part of Western politics to keep markets completely open to any type of Chinese investment.”

Despite this drop, China remains among the world’s leading investors, and in the first 10 months of 2023, official statistics placed total OFDI at $123.9 billion, up 5.4% on the previous year. But it is where the money is flowing to that comprises the biggest change from the 2016 peak.

Away from the West

As total investment slows down and the geographical and industry-specific focus of Chinese investment shifts, Chinese firms are increasingly investing in infrastructure projects and sectors aligned with the country’s national development goals.

“I think China has always looked at outward investment strategically, and part of this is because so much of it could be driven by state-owned enterprises,” says Bolwijn. “As a result, you can draw a line between their needs and the investments they make. They need market access, technology access and also to strengthen political links throughout the world.”

While the decline in Chinese investment to Europe is largely due to changes in Chinese domestic regulation, European countries have also continued to increase scrutiny of Chinese investments across the board. By the end of 2022, all except two EU member states had investment review mechanisms in place or were in the process of establishing them.

By tightening investment screening measures, Europe is limiting investment into strategic technological assets such as semiconductors. In a related development, there was also heightened scrutiny of a Chinese investment into a port terminal in Hamburg, Germany, in 2022, but the deal was still approved by the German government.

While investment into the United States from China has also shrunk significantly, the US continues to maintain its position as the top national recipient of Chinese investment. But from a US perspective, China has gone from being one of the top five investors to being only a second-tier player.

The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) now strictly reviews Chinese investment into the US, especially in cutting-edge technology and critical infrastructure, such as semiconductors and telecoms systems. Looking ahead, headwinds are only likely to increase.

“China’s global strength in high-end manufacturing products—smartphones, EVs, and renewable energy products—will inevitably seek global markets and are increasingly succeeding in MENA, Asia and Africa,” says Shirley Ze Yu, Professor and Senior Practitioner Fellow with the Ash Center of Harvard Kennedy School. “The products have not been successful in entering the US and European markets due to trade restrictions and various sanctions on grounds of national security and human rights violations.”

Investing in advanced economies generally brings investors increased revenues and higher profit margins, and M&A is often a quick way of increasing technological knowhow. But, growing geopolitical tensions and increased decoupling between China and the West—particularly the US—is dampening investment returns and hampering the further international development of many Chinese companies.

Embracing the new

Much of Chinese outward investment in recent years has been spurred on by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and despite changes, it continues to be a driving force. “There was certainly a slowdown in the implementation of BRI projects a few years ago, mostly because of the concerns with debt problems,” says Michelle Lam, Greater China Economist at Societe General. “But more recently there has been a pickup in BRI interest and projects, particularly in green investments.”

Contrary to the fluctuating global trend in China’s outbound investment, Chinese investment within Asia—especially Southeast Asia—has increased, surpassing the 2016 peak. In 2022, according to the MOFCOM Statistical Bulletin on ODI, China invested $18.6 billion into ASEAN countries, accounting for 11.4% of China’s total outbound investment flows.

Singapore has historically been, and remains, the largest recipient, accounting for around 33.5% of the total ASEAN-bound OFDI, but countries like Indonesia and Malaysia in particular have seen a notable rise in investment since 2017. Thailand and Vietnam are also of growing interest to Chinese investors.

“In the ASEAN area, if you go back a decade, much of the Chinese investment was in mining,” says Tommy Xie, Head of Greater China Research & Strategy at OCBC Bank. “While there is still a lot of that going on, there has been big growth in commercial services and, more noticeably, manufacturing.”

The ASEAN manufacturing sector, particularly related to EVs and renewable energy, is the largest recipient of this investment, accounting for around 44% of the total. Carmaker Geely has invested in Malaysia’s Proton, battery maker CATL entered into a joint venture in Indonesia to secure nickel supplies and produce batteries, and in 2022, four of the top five full EV car models produced in Thailand were Chinese.

“There are areas of overcapacity for some Chinese companies, and, for example, the prices of EVs and solar panels in China are very low right now,” says Chim Lee, Analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit covering China and Asia. “At the same time, many of these developing markets have similar ways of organizing their economies as China, so if companies are looking for a new market, these developing markets offer any number of opportunities for Chinese companies.”

There has also been a growth of cash flowing to sectors such as critical raw materials processing and internet platforms, compared with the emphasis on conventional real estate and light manufacturing investment in past years. E-commerce in particular is a major target, with the non-food and beverage section of the market projected to triple in size and reach $230 billion in gross merchandise value by 2026, according to McKinsey & Co.

All of China’s e-commerce giants have made some form of inroad into the Southeast Asian markets, with Tencent, Alibaba, Byte Dance and JD.com all either signing partnerships, launching products or setting up operations in various countries across the region.

“If you are a tech company in China, you are also looking for other areas in the world that have a somewhat similar style of economy as China that will provide good investment returns,” says Lee. “As a result, we have seen a huge growth of Chinese e-commerce companies operating across Southeast Asia. For example, TikTok Shop has been hugely successful in Indonesia.”

The Middle East has also seen an uptick in Chinese interest in trade, deals and investment, but it remains the recipient of only a small portion of the total OFDI. Investment into Middle East as a whole in 2022 was only around $2.62 billion.

“China has long been dependent on oil imports and that has dominated its trade with the Middle East in the past, but we’re starting to see a wider range of trade sectors and an increase in bidirectionality,” says Duncan Wrigley, Chief China+ Economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics. “For example, Saudi Arabia has a long-term ambition to diversify away from oil, and it also has a lot of spare money because of recent oil price surges, and as a result, we’ve seen an increase in bilateral agreements. As US private equity firms pull back from investing in Chinese tech startups, Saudi investment funds are considering filling the gap, with a mind to bringing Chinese knowhow and technology into the country.”

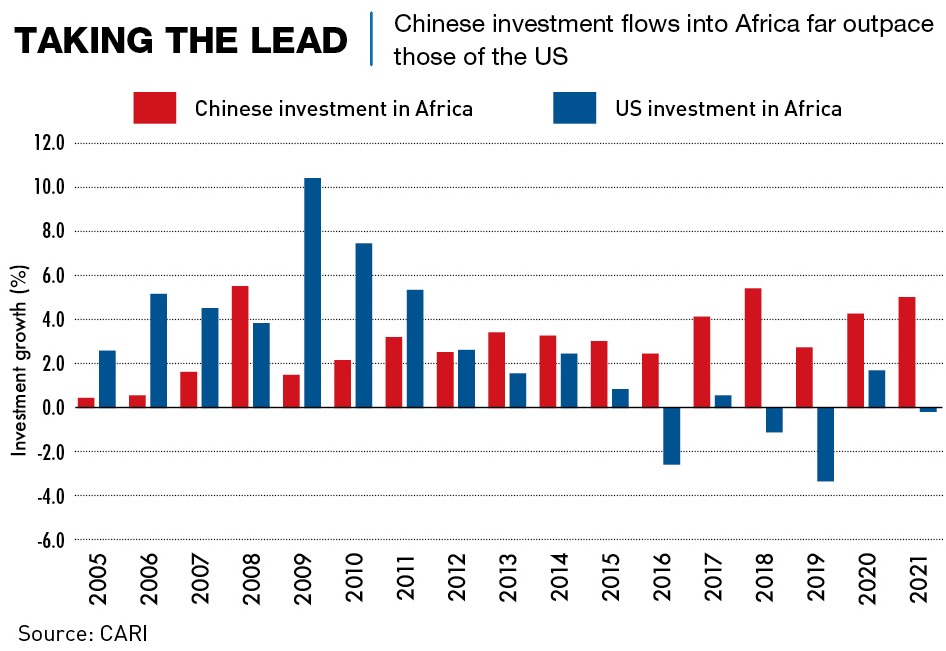

There have been larger shifts in investment into other regions such as Latin America and Africa, which had the two highest increases in 2021, largely driven, at least initially, by the BRI. For example, China’s annual flows of OFDI to Africa peaked in 2018 at $5.4 billion, up hugely from just $74.8 million in 2003. Despite a dip to $2.7 billion in 2019, recent years have seen a recovery and by 2021 it was back to around the $5 billion mark.

“One of the ways that we see Chinese OFDI recalibrating global supply chains is extending middle-to-low-end supply chains to the developing world, most prominently in ASEAN, Latin America, and increasingly in Africa,” says Yu.

Chinese companies operate across a wide range of sectors in Africa, with around one-third involved in manufacturing—including resource production, a quarter in services and a fifth each in construction/real estate and trade. The split of Chinese OFDI by country largely correlates to China’s resource interests with around three-quarters of the investment split between 12 resource-rich countries in 2020. Overall, according to McKinsey estimates, around 12% of Africa’s industrial production is now done by Chinese firms and Chinese companies make up around 50% of the continent’s internationally contracted construction market. For example, in 2022, Huawei technology constituted around 70% of Africa’s 4G infrastructure.

“If you look at investments in rare metals such as nickel or lithium in the Congo, and elsewhere, China has just been a step ahead of everyone else, just faster and bigger,” says Bolwijn.

For Latin and Central America, 2021 saw an almost doubling of investment from China, reaching $27.3 billion. Brazil was the lead recipient thanks to a huge investment in the oil sector, followed by Colombia, Chile and Mexico. Deals in the region are largely focused on natural resources, such as oil, but many of the investments in Peru and Chile have been focused on copper, and other mineral mining operations.

“Chinese OFDI in acquisition of energy, natural resources, and agricultural products are increasingly shifting from North America to Latin America and Africa, in response to the geopolitical risks,” says Yu.

Accepting change

The Global South’s embrace of Chinese investment is no surprise. Compared with the reluctance toward Chinese capital in the West, local regulators, whether in Southeast Asia or Latin America, still mostly welcome Chinese investment. Governments in the developing world are also expressing interest in working with China as a business partner. Shifting production to countries such as its Asian neighbors and Mexico will not only offset high labor costs in China, but also enable Chinese firms to avoid trade tariffs, remain close to Western markets and even enjoy duty-free treatments.

“It is very much the case that Chinese companies want to maintain access to the markets in Europe and the US, and we can see that in supply chain investments,” says Lee. “China often remains a major part of the upstream supply chain, then a product is completed somewhere like Mexico, Turkey or Hungary, and exported to one of the Western markets. Although there is always the risk that the US or EU may scrutinize this process more.”

“To some extent, the ASEAN markets have become something of a refuge for Chinese companies that want to continue doing business with the US population,” says Xie.

Securing access to critical resources is of strategic importance for China—especially companies in renewable energy sectors. Metals such as copper, lithium, cobalt and nickel, are essential for solar photo-voltaic, wind energy, electric vehicles and energy storage, and China is determined to ensure its dominance by controlling overseas mines containing critical minerals. But there are several examples of larger countries being more demanding with their side of potential contracts in order to ensure a certain level of local development from Chinese investment, rather than simple resource extraction.

“We see, for example, Indonesia and some Latin American countries setting up barriers in terms of exporting materials, requiring Chinese players to set up some processing plants locally,” says Lee. “This is mostly to ensure that they provide economic value locally, rather than just going in and removing the resources.”

The significance of the shift in China’s investment pattern does not stop here. In many cases, particularly in Africa, China is trying to foster local markets through its investment strategy and grow together with the developing countries. By doing so Chinese companies have the chance to get in on the ground floor of new markets, with little competition. China’s ambition is to invest in the infrastructure and industry sectors in the BRI countries, drive economic growth, and ultimately increase the consumption power of the local population.

“Taking the renewables market as an example, if you want to expand the sales of that kind of infrastructure, you also need to build the energy infrastructure to deliver the grid space,” says Bolwijn. “That can also lead to building more ports, airports and roads to build power infrastructure. It is synergistic in a way because if you want to be successful in certain areas, you need to expand in others.”

By being a part of market development rather than simply a participant in the market, China wins preferential access to contracts, consumer goodwill and even soft power influence.

A wider issue

While investment continues at a lower level into the West, the shift towards developing markets for China’s OFDI is a reflection of a wider decoupling and looks set to continue.

“The tensions with the US and to a lesser degree Europe, have highlighted the need for China to become self-sufficient in some areas, but realistically it cannot be completely isolated,” says Wrigley. “This has resulted in a diversification of investment, trading and political links and the promotion of its currency.”

Lam agrees. “The trade difficulties in 2018-2019 were a turning point, which pushes the government to focus more on security and I don’t think that priority will change in the near future,” she says. “One thing it may mean is that some of the investment targets China is approaching will have to think about choosing sides.”

China is taking a more holistic approach to its OFDI, looking to play a part in the creation of markets rather than simply being a participant in already developed markets, but the shift will be neither quick nor easy.

“In the short term, it’s very difficult to replace developed markets as investment targets,” says Wrigley. “But if you look a few decades down the road, then it does become more plausible that some of these developing regions can be equally important for China as the most developed markets currently are, for both trade and investment flows.”