Chinese startups claim they can use your genes to predict sporting ability. Can they?

20 years ago, the science fiction film Gattaca put forward a startling premise: Would genetic modification lead to different classes of people? Would designer babies have increased health and longevity while natural-born children were left to deal with the frightening risks buried within their own genetic code?

A number of Chinese companies are now betting their future on uncovering these hidden genetic traits for willing customers. Take Ran Yingying, for example. A former state television hostess, widely known as the wife of Chinese World Boxing Organization flyweight champion Zou Shiming, Ran recently drew attention for posting her son’s test scores online.

These results were not from any academic test; rather, Ran had given her six-year-old son a commercial genetic test which had come up with a series of figures that covered everything from his ability to learn languages through to music appreciation, sporting ability, interpersonal skills and his aptitude for mathematics.

“It looks like that China’s most successful boxer’s son did not get his father’s sports gene,” Ran said, mostly in jest. Her post was forwarded over 40,000 times, with many comments saying they want to perform similar tests themselves or for their kids.

It’s common for celebrities to post test results such as these. In fact, Chinese companies often use the case of Hollywood A-lister Angelina Jolie to persuade customers to sign up. Jolie used genetic testing to discover that she had a high risk of ovarian cancer and consequently had ovarian removal surgery.

Of course, the reliability of the science of using genetic screening to determine risks of cancer is worlds apart from using these tests to determine sporting or mathematical aptitude.

It was for this reason that in late 2015, 22 experts in the fields of genomics and sports published a statement in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, which said that no child or young athlete should be subjected to genetic testing to spot sporting talent or boost performance. They concluded that the scientific evidence on the effectiveness of these commercial tests is “simply far too weak to back their use”.

But with progress on genetic research proceeding at a fast pace, public demand is running high regardless. Startups are already offering a wide array of genetic tests, be they screening for health risks or predicting personality, with varying levels of scientific support.

Market Demand

“These [tests] are an effective marketing method for firms offering services such as gene technology, which seems too high-tech for people outside science laboratories. They have suddenly become relevant, cheap and available for all of us,” says Li Qi (pseudonym), a researcher at a genetic lab in Peking University.

The test taken by Ran Yingying’s child cost 6,500 RMB and was developed by Daan Gene, a Guangzhou-based genomic company, which only began offering personal gene test products in 2015. Affiliated with Sun Yat-sen University, it had been focusing on research-related gene studies and working with institutions. It was only in the past two years that it started targeting members of the public as customers.

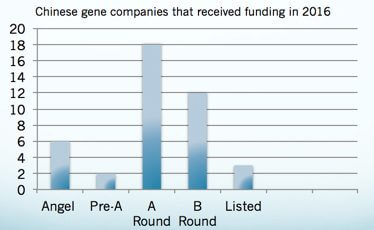

In China, there are over 150 genomic firms. Currently, 70% of them are mainly offering gene test services and an increasing number of them have started to offer tests to individual consumers. With attractive advertisements and the mysteriously advanced gene technology, genomic firms have become attractive choices to investors. A rough calculation by CN-HealthCare says that 40 Chinese gene companies received investment in 2016, worth over RMB 80 billion in total.

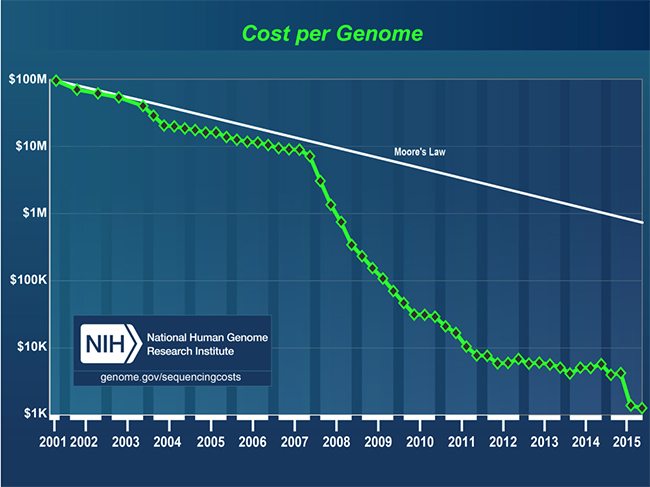

According to Li, an important factor that contributed to the popularity of gene testing is the rapid decrease in genetic analysis costs. According to the National Human Genome Research Institute in the US, genome sequencing costs started to fall sharply in 2007, when the cost per genome was around $10 million. In 2015, the number had dropped to less than $1,000.

She says that commercializing gene testing has both risks and benefits. With more people participating in gene tests, more data will be collected and R&D will advance, but there might be more public misunderstandings as companies conduct scientifically questionable “talent and personality tests” to meet public demand.

As these businesses increasingly target the public, two types of gene companies have formed: on one side there are the traditional gene technology companies which entered the market before 2012, like BGI, which keeps developing sequencing equipment and technologies and cooperates mostly with research institutions and health organizations; on the other side are the startups which target individual customers and promote the commercial use of genomics.

Young startups frame the debate as established gene companies turning their back on ordinary consumers, while traditional companies claim that many of these consumer-focused businesses are distorting the science. Li Ruiqiang, the CEO of Beijing-based Novo Genomics, says his company would never offer talent tests, as they only choose to do things “that are scientifically reliable.”

But at the same time, there are also companies like Daan Gene who cover both professional and personal tests. “As a leading company in the gene industry, it’s our responsibility to help more people learn about gene studies, with lower prices and from a simpler angle,” said a spokesperson at Daan Gene in 2015 to Chinese business newspaper 21st Century.

A Changing Industry

In 2009, 95% of companies in this industry were focused on selling to business and institutions, and providing services for science studies in universities and research institutes, says Zheng Hongkun, CEO of BioMarker, a Beijing-based gene company. “There was no commercial product for individuals,” he says. As the cost of genome sequencing fell, non-invasive prenatal tests (NIPTs), which pregnant women run to determine whether a fetus has genetic disease, has become the most popular gene-related application.

China has strict rules for public hospitals that want to distribute gene products that are developed by private companies—an official approval from the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) is needed, but in a general sense the official attitude appears to be favoring the wider use of gene technology in medical areas. In 2015, the Chinese health ministry for the first time allowed 107 hospitals to conduct NIPTs. One year later, the ban was lifted—all hospitals with an obstetrical department can do the test.

Worldwide, DNA-based tests are available for over 1,500 diseases of different ages, yet so far in China, the NIPT, which costs about RMB 2,000 per test, is the most common gene test and screens for three kinds of genetic disease.

Although the government has allowed nearly all hospitals to conduct NIPTs, these tests, involving widely accepted science, still aren’t a direction many startup companies plan to specialize in. This is largely because two companies, Berry Genomics and BGI, basically dominate the NIPT service market, leaving slim opportunities for newcomers.

Zheng founded BioMarker in 2009, after working at BGI for nine years. The company, with an estimated market value of RMB 1 billion after receiving 100 million in funding in late 2015, has been developing sequencing technologies and providing data and sequencing services for research institutes. He says the company will put more effort into developing genetic applications for early tumor detection and more precise medical treatment. “Apart from reproductive health, tumors are the other area in which genomics can play an important role,” he adds.

It is widely accepted that the upstream sectors of the industry, like materials and equipment production for gene sequencing, have been dominated by foreign companies like Illumina and domestic giant BGI. In the middle there are mainly companies capable of providing sequencing and gene tests. Downstream, gene data mining and analysis remain challenging areas but have biggest potential, says Zheng. “In order to apply this to disease detection and medical treatment we need more data that we can study and experiment on.”

Huang Jinzhang, former editor-in-chief of the Phoenix Weekly, after doing gene tests twice, started the genetic company “Gese DNA”, which focuses on providing “readable content”. The aim is to present the information in a straightforward way, without technical jargon or figures.

“I did gene tests twice in 2013, with a very famous genomics company, very professional, and they gave me a report, a 14 megabyte document full of gene codes, which I could not decode myself,” Huang told China Newsweek magazine in December 2016. Later he decided to develop a company that is more “user-friendly”.

The package offered by Gese DNA, which costs RMB 499, claims to answer your questions relating to six aspects about your health and character, for example, how fast you can learn new things, if you’re easily addicted to something, or if you have an introverted personality. If you are man, it tells you the probability that you will go bald.

Compared to medical uses like NIPT and tumor treatment, personal gene tests, which purport to answer people’s questions about their health, lifestyle and personality, tend to be more explicit, have less scientific backing, and are less regulated.

On Taobao, China’s largest online e-commerce platform and which has clear rules banning the sale of these genetic products, gene test packages, with prices ranging from RMB 99 to 2,999, can still be found in at least 40 stores. Most of them target parents who want to find out about their children’s talents.

These tests, though recognized by many people and favored by start-ups and VCs, remain controversial. Huang Shangzhi, professor at Peking Union Medical College Hospital, says there are certain genetic markers that can give some very general information about people’s talents and personality, but there is really no way to measure the accuracy of these tests. “If a parent forces their child who tested positive to sporting talent to become an athlete even though the child prefers piano, or if an employer wants to see the test results, there are obvious ethical problems.”

A Controversial Business Model

Ethical issues and accuracy are not the primary concerns for many business people. WeGene, another personal genetic company, generates not only talent reports but also gives health resolution packages like advice on losing weight or curing insomnia.

This is a common business model applied by companies—selling health solutions to consumers.

This is partly because cost thresholds are being lowered. As the technology becomes more advanced, gene test costs will be further lowered or even free, and companies will have to make money by providing health solutions, says Cheng Gang, deputy manager at Daan Gene.

Since it’s clearly regulated in China that private genomic companies are not allowed to give medical diagnosis or treatment, these companies fall into a grey area. They can also choose to work with formal hospitals and health institutions, but such organizations tend to cooperate with more technology-oriented companies like BioMarker and BGI.

There is another way out—data collection.

We Gene claims to be the Chinese equivalence of 23andme, a California-based role model that most Chinese genomic companies learn from. Initially a personal genetic startup, 23andme has now become a “research company” that partners with drug developers and medical institutions. In 2015, it announced a deal with Pfizer, giving the giant drug maker access to the data it collected from 650,000 individuals.

The company first became controversial because of the ethical problems relating to talent tests, then it was blamed by the US FDA for offering medical suggestions, and now it is accused because people’s gene privacy can’t be guaranteed, although it claims to only include people who have agreed to let their data be used in research.

Marcy Darnovsky, executive director of the Center for Genetic and Society, wrote in an article criticizing the company: “once you part with your genetic information, there can’t be guarantees of privacy and anonymity.”

So the question then becomes, will 23andme’s Chinese acolytes follow a similar path to monetization by selling data? Cheng says that companies like Gese DNA and We Gene can accumulate a lot of data, which is a core component for any genetic research.

For companies like BioMarker, gene data collection is even more important, as they need the data of both normal, healthy people and those of sick people in their studies. The problem is that companies who have access to mass gene data are not combining their data resources.

Personal gene test startups can see a path to becoming a data-oriented research company, if they can get enough private data (and permission to use it). Or, they can try to develop their medical teams, partnering with hospitals and health institutions and offer health solutions, becoming more service-oriented.

Professor Huang says that China lacks trained genetic consultants. “The gene test results are useful tools for clinical diagnosis and treatment, but only people with both genetic knowledge and clinical experience can make sense of the gene data. Only an estimated 5% of doctors in China are qualified,” he adds.

The qualifications to decode genes could be a determining factor for startups, he says. For talent tests, accuracy might not be vital. But medical treatment is different.

In regard to the future of gene industry, Huang says that “gene tests” cannot be an industry by itself. “While ensuring data security, companies will have to work together to share and integrate data resources to develop either health consultancy for ordinary people or disease treatment for the medical industry. In either case these gene companies cannot work alone, they have to work with hospitals, drug makers or other research institutes.”