China has a vision to digitalize its manufacturing sector. How is it doing on its path to achieving that goal?

The microwave oven in your kitchen hardly counts as cutting-edge technology these days, but the factory built by Midea Group in southern China’s Foshan to manufacture millions of them every year certainly does.

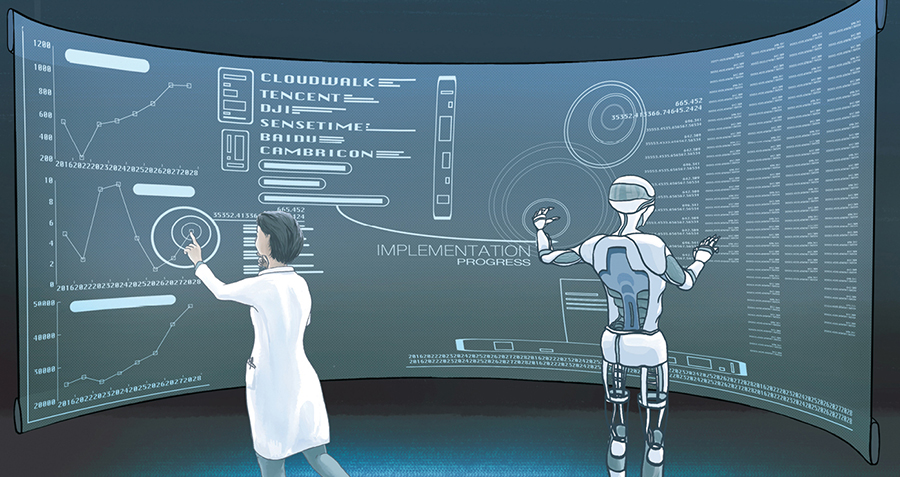

Automated production lines in the pristine factory beam operational data via 5G networks to an industrial internet platform, while a handful of engineers watch a giant screen for alerts indicating problems in a production process which cranks out more than 44 million microwaves annually.

Thanks to digitalization and automation, the state-of-the-art factory has shaved production costs by 6%, more than halved order delivery times, and lowered carbon emissions by one-tenth. These improvements have won international acclaim for Midea, now the world’s biggest home appliances maker—in March, the World Economic Forum selected the Foshan factory as a member of its ‘global lighthouse network’, which recognizes plants leading the way in the adoption and integration of frontier technologies.

Of the 69 “lighthouse” facilities worldwide, 20 are in China, including the high-tech Tsingtao brewery in Qingdao and Alibaba’s pilot factory for “smart manufacturing” in Hangzhou. These are only the most visible parts of the ambitious digitalization plans being implemented by Chinese manufacturers.

But the degree of automation varies widely between different industries, says Georg Stieler, managing director for Asia at STM, an international consultancy specializing in B2B market research and strategic management for companies in the engineering industry. “Whereas some automotive factories in China are basically on the same level of automation as in early-industrialized countries, we still have a low degree of automation in light industries.”

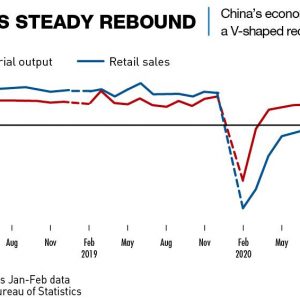

Still, the gains won via digitalization at Midea’s factory demonstrate the appeal for manufacturing, and the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically underlined the importance of digitizing factory operations. Fewer staff means less disruption, and digital production allows for much faster readjustments to production, such as switching suddenly to the mass production of masks, gowns, gloves and other personal protective equipment (PPE), as many factories did in early 2020, including Midea, fellow white goods maker Gree and automaker BYD.

Such efficient transitions could only be achieved with digitalized management of inventories, manufacturing processes and the labor force, as well as a high level of industrial automation based on digital design, modelling and 3D printing, according to Wilson Chow, leader of the global technology, media and telecommunications practice at PwC China.

“Digital capabilities are an increasingly important factor for manufacturers’ ability to respond to changing customer demands, better manage supply chains, build resilience and maintain sustainable growth,” says Chow.

Automation nation

With an enthusiasm for automation that begins at the top—China’s leader Xi Jinping called for a “robot revolution” in a 2014 speech—the Chinese state is throwing itself fully behind a push for automation across its vast economy, looking to revolutionize everything from agriculture to assembly lines.

Chinese manufacturing’s embrace of digitalization shows up most prominently through the use of industrial automation—a market worth an estimated RMB 62.7 billion ($9.6 billion) in China last year, up from RMB 58.1 billion in 2019 and RMB 61.1 billion in 2018, according to MIR, a Beijing-based research firm specializing in industrial products.

The money is mostly being invested in equipping factory floors with robots to churn out high value-added products like cars and electronics faster and with more precision. But increasingly, robots are cropping up in other sectors of the world’s second-largest economy, performing tasks previously handled by humans with greater efficiency than ever before.

China’s rising labor costs and looming labor shortages in the coming years are important drivers for increased automation, which offers efficient and cheap manufacturing capabilities that officials hope will solve the problems, says Wang Jiegao, chief scientist at Estun Automation, a Nanjing-based supplier of industrial robots and robotic components listed on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange.

“Factories have found it tougher and tougher to hire manual labor workers. The situation has become progressively worse in recent years, especially since the onset of the pandemic last year. There are more and more companies that are urgently investing in automation and robots,” says Wang.

Song Xiaogang, secretary general of the China Robotics Industry Alliance (CRIA), an industry association, recalls visiting factories a decade ago in China’s manufacturing heartlands of the Yangtze River and Pearl River deltas that were already struggling to find enough workers to fill production lines. “They were under big pressure to get employees because the younger generation started to dislike heavy-duty work.”

The robotics industry in China enjoys strong government support and a myriad subsidies from both central and local authorities. Robots first entered national strategic planning in 2006 as part of the National Medium and Long-term Science and Technology Development Plan (2006-2020), and in 2015 were elevated to be a core component of the Made in China 2025 industrial policy, aimed at making China self-sufficient in key technologies.

A year later in 2016, Beijing published the Robotics Industry Development Plan which laid out how the industry should reach end-2020 goals of domestically producing 100,000 robots annually and achieving a robot density of 150 robots per 10,000 manufacturing employees—both of which have been accomplished.

“Before 2015, China was working with robots in much more limited ways than it is today. It was mostly in automotive and a little in electronics, but not much outside of those,” says Emil Hauch Jensen, China general manager at Gain & Co, an independent advisory on robotics and automation.

Government support has helped kickstart more than 1,000 robotic automation startups in China since the start of 2015—a record 367 were founded in 2016 alone, according to Gain & Co. There were close to 4,000 such companies in operation by the end of last year, quadruple that of 2009.

Do the robot

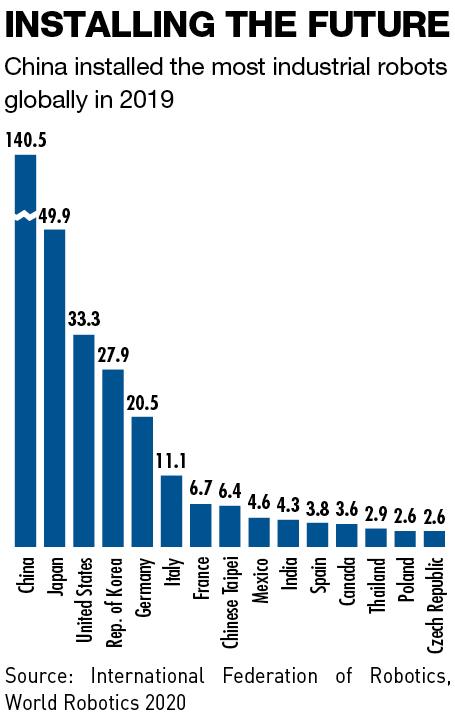

Even before the pandemic, China was well on its way to automation—particularly in the electronics, automotive and logistics sectors. China overtook Japan as the world’s largest market for industrial robots in 2013 and in 2019 accounted for 38% of new installations, according to the International Federation of Robotics (IFR).

But the COVID-19 outbreak supercharged China’s automation journey, says Chow. “As overseas demand boomed last year, China really needed to speed up efficiency and automation in order to not be heavily reliant on its locked-down human workforce.”

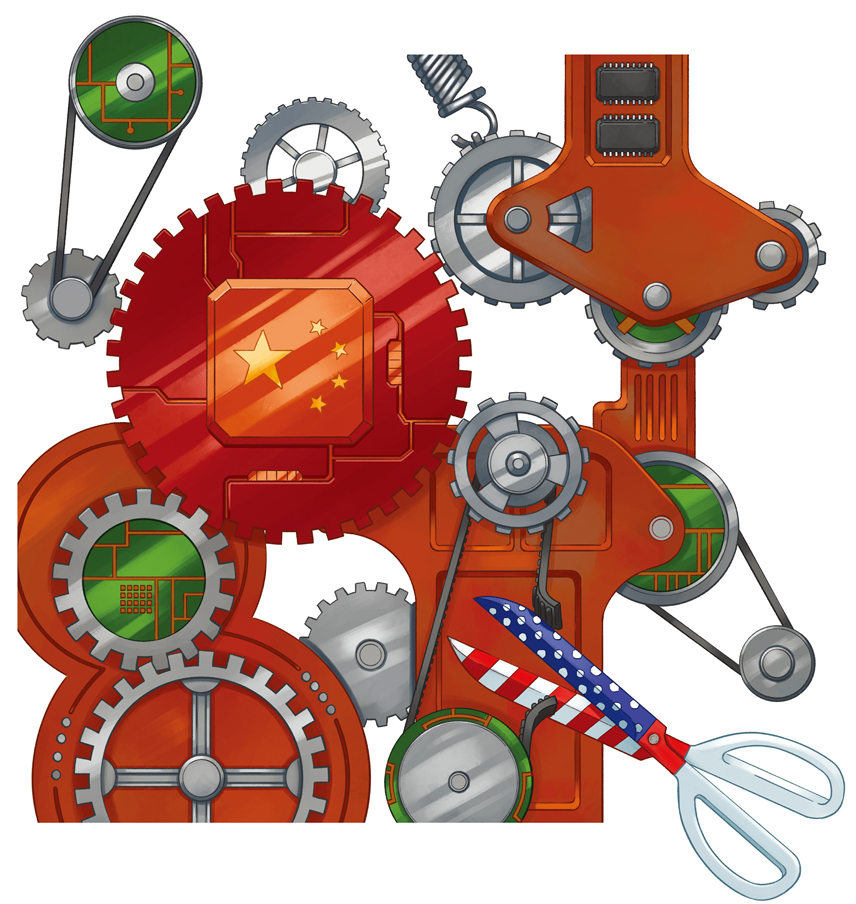

The enthusiasm for robots has led some Chinese manufacturers to venture overseas for foreign knowhow, the most prominent example of which is Midea’s €4.5 billion ($5.3 billion) acquisition in 2016 of Kuka—the Augsburg-based company once regarded as one of the pearls of Germany’s manufacturing industry. The Chinese company overcame considerable political friction in Berlin and opposition within Kuka itself to clinch the deal, a sign of how much it valued the German giant’s high-tech robotic and automation technology.

“It was a great win for Midea and for China,” says Jensen. “It was probably a combination of this deal and other factors that alerted Europe and the US to China’s intention to compete.”

Industrial robots continue to be installed in China at a staggering rate across industries, with 140,492 added in 2019, more than the next four-largest markets of Japan, the US, South Korea and Germany combined.

“China is a special market because it is so much bigger than all the others and has so much labor-intensive manufacturing,” says Wang from Estun, the industrial robot supplier. “The demand for automation to replace labor work provides a much bigger market.”

Automation has helped China maintain its status as the factory of the world even as its manufacturing workforce shrinks. China’s value-added industrial output reached RMB 31.3 trillion ($4.8 trillion) in 2020, equivalent to nearly 30% of global manufacturing output and up from RMB 23.5 trillion in 2016. High-tech manufacturing in particular clocked average annual growth of 10.4% in value-added output between 2016 and 2020, despite official statistics showing a contraction in China’s urban manufacturing workforce from a peak of 79.6 million workers in 2014 to 71.9 million in 2018.

Automation in Chinese factories is concentrated in the use of industrial robots—a category where China punches well above its weight, with more sold in the country than in Europe and the Americas combined.

Four suppliers, ABB, Kuka, Fanuc and Yaskawa Electric, dominate the market for industrial robots, but the fast pace of innovation has helped broaden the types of robots in play, from traditional welders and palletizers to more futuristic categories such as collaborative robots (‘cobots’) and autonomous mobile robots.

With Chinese factories continuing to rely heavily on foreign robot makers, domestic robotics companies still need to address their lack of competitiveness in the higher reaches of automation. “Even though China is a major producer of industrial robots, the types it is manufacturing are still more geared toward the lower end of the production process. Higher-precision types of robotic technology are still in the hands of the Europeans and Japanese,” says PwC’s Chow.

For decades, robots were heavy, bulky machines caged off for safety because they were hard-programmed to follow a preset path without regard for any humans in the way. But with better sensors and more powerful software, robots are becoming smarter and more flexible. For instance, advances in machine vision are helping Chinese firms develop cobots that can recognize what is in front of them and decide which parts to pick up and how. Increasingly, they are designed to work in close proximity with humans.

A smarter Factory of the World

Even with all of these new developments, however, a future fleet of hyper-advanced robotic factories that run themselves with inhuman efficiency and speed is some way off.

“We need quite a long time to reach that level,” says Song Xiaogang, secretary general of the China Robotics Industry Alliance (CRIA), an industry association. “China has so many different manufacturing sectors. Some of them can compare with the world’s most advanced digital manufacturers such as Siemens. Then there are some very traditional manufacturing sectors that are taking baby steps toward automating some processes. Overall, the level of digitalization in Chinese manufacturing has a long way to go.”

China’s robot density—measured as the number of robots per 10,000 manufacturing workers—is one of the lowest among major manufacturing nations. In 2019, China had 187 robots installed per 10,000 employees, ranking 15th and below Italy, Spain and Austria, according to the IFR. Singapore and South Korea top the charts with robot densities of 918 and 855 respectively. But factories in China are pushing for automation with an enthusiasm unmatched by peers in other manufacturing nations, says Jensen from Gain & Co.

“In China, we see a lot of smart manufacturing ambition, with customers wanting to go all the way with a fully digital factory that comes with analytics, Internet of Things (IoT) and robots. In the US and in Europe, customers are usually content with easy wins like automating small specific processes. For them, smart manufacturing is still five years or more down the road.”

But that won’t necessarily result in massive unemployment. Apart from high-tech precision jobs that even humans cannot do, many robots are being used to fill undesired ‘4D’ jobs—dull, dirty, dangerous and/or delicate—meaning that the impact of automation on employment in China could be perhaps less severe than has been feared. “I haven’t seen any signs that robotics adoption has influenced employment,” says Song. “Remember, for the traditional manufacturers, the main reason they want to use automation or robotics is because they struggle to find new workers.”

Song argues that automation has in many cases been a job creator as companies have sprung up to cater to the growing demand. He points to the swelling membership of the CRIA, which has grown from 70 members when it was founded in 2013 to nearly 500 today.

A large industrial base, the can-do spirit of Chinese businesspeople and an openness for new things will continue to catalyze automation in China, says Stieler. “Constant change is in the modern DNA of China’s people. Leapfrogging also happens in automation, as some companies are turning the lack of legacy infrastructure into an opportunity.”

But the general sense is that China’s manufacturers need to learn to walk before they run off to build fully-automated smart factories. “I don’t think we need to hurry. It’s a step-by-step process. This is the best way for the most of Chinese manufacturing,” says Song.

Manufacturers would also do well to bear in mind what one of Jensen’s colleagues told him: “Smart factories are rare as unicorns; we’ve never really seen one.”

But as Midea’s microwave factory in Foshan demonstrates, Chinese companies have the means and the motivation to achieve digital manufacturing excellence.

“The big dream is intelligent, unmanned factories that can make and deliver products with drones or self-driving cars and so on,” says Jensen. “I don’t know exactly when they will happen. But I know that they will be in China before anywhere else.”