Smear campaigns are hurting businesses in China. Here’s how some smart reputation management can help.

In China, the benevolent cartoon of Master Kong—pudgy, cheerful, topped with a white chefʼs toque—is the face of instant noodles, the ubiquitous logo that grins out from supermarket shelves. The brand has the largest market share in Chinaʼs instant noodle business, with flavors to tempt taste buds from Shanghai to Kashgar, as well as assorted other beverages and snacks. Tubs of dry, uncooked Master Kong noodles, sold for roughly 4 yuan, are a staple in Chinese dormitories and train stations. Thereʼs even a Master Kong noodle-making museum in Tianjin, where the company was founded by brothers from Taiwan in 1992.

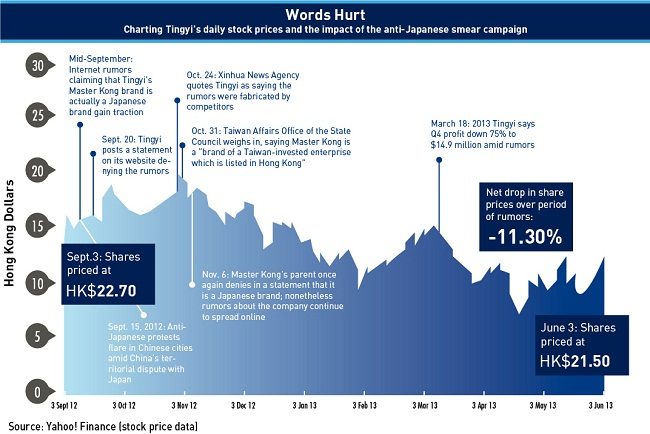

Understandably Chinese consumers were taken aback when accusations appeared on microblogs late last year claiming that the Hong Kong-listed maker of Master Kong, Tingyi (Cayman Islands) Holding Corp., was actually a Japanese company in disguise. The rumor broke out during Chinaʼs territorial dispute with Japan over the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands in the East China Sea, when mainland rioters were smashing Japanese cars and demolishing sushi shops. Some microbloggers claimed that Master Kong, Chinaʼs noodle king, had donated JPY 300 million (RMB 19.2 million) to Japan to purchase the disputed islands. They incited followers to “spread the message, and let all our countrymen know!”

University students organized boycotts. Photos of Master Kong products appeared on banners at anti-Japanese demonstrations. An unnamed Tingyi executive quoted in the China Times blamed rival company Uni-President for the rumors, a charge the competitor denied. Throughout the crisis, Tingyi released statements refuting the allegations.

And yet the ridiculous-sounding rumor proved disastrous: Tingyiʼs share price slid from about HK$24 (RMB 19) to about HK$20 (RMB 16) from mid- September to early January, as documented by Chinese media blog Danwei. The companyʼs net profi t plummeted 75% in the last quarter of the year, dropping to $14.9 million (RMB 91.4 million). What happened?

Gossip, Rumors and Lies

Rumors, always potent in an age of social networking, are especially dangerous for companies operating in China, public relations specialists say. In one case, the share price of leading search engine Baidu dropped late last year amid rumors that cofounder Robin Li was divorcing his wife. Li was forced to broach the subject—awkwardly—while accepting a business award in December, denying the rumor and blaming unnamed competitors. In January, rumors spread on the internet in China that Coca-Cola Co.ʼs Minute Maid orange juice contained a harmful pesticide. The company swiftly issued a denial, said it had filed a police report about the rumors and reassured consumers that Chinese health officials had tested the juice and pronounced it clean. In such cases, itʼs often difficult to pinpoint where the gossip originated, though thereʼs a tendency to blame competitors.

There are a host of reasons why rumors proliferate in China: in a country where information is tightly controlled, many here are skeptical of offi cial news outlets and sources of authority. “[The government argues that] the web must be actively policed to prevent the spread of harmful rumors… The reality, of course, is that China prevents free flow of information, creating an environment where rumor and gossip fl ourish,” says Steven M. Dickinson, a lawyer with Harris & Moure and co-author of the China Law Blog. While the State Internet Information Office cracks down on some rumors—as seen in a recent wave of arrests of users spreading panic online about the H7N9 bird flu virus—it focuses only on those deemed especially sensitive. Most business-oriented rumors go unchecked.

Companies themselves often arenʼt transparent with investors and media. Though Tingyi issued public denials throughout the Master Kong crisis, it hasnʼt always been forthcoming. In 2011, a blog for The Wall Street Journal recounted how Master Kong annoyed shareholders and reporters by barring them from an analystsʼ briefing on a strategic alliance with PepsiCo Inc.

In China, “many companies are extraordinarily non-transparent, even to the point that basic information you would expect as an investor is not disclosed,” says David Wolf, Managing Director of the Global China practice of Allison+Partners, a San Francisco based PR firm. “Itʼs a perfect breeding ground for mistrust. Itʼs a petri dish for rumors.”

In the case of Master Kong, hidden amid the rumors was a grain of truth. Though Taiwanʼs Ting Hsin International Group owns the largest stake in Master Kong, 33.27%, Japanʼs Sanyo Foods Co. Ltd. has the second-largest stake, with 33.18%. Some consumers might not have been aware of that, and the over-the-top rumors drew their attention to it.

The World of “Dark PR”

In a cutthroat business environment, thereʼs an entire industry devoted to business misinformation. So-called “black PR” fi rms sometimes recruit people toTaiwanese subsidiary of Samsung recently faced allegations that it hired people to write fake reviews bashing a competing cell phone, the HTC One. Sometimes, all it takes is a well-placed comment from an opinion leader with a few thousand followers on Weibo, and a rumor might go viral. Sam Flemming, Founder and CEO of Chinaʼs CIC, a social business intelligence provider, pores over online chatter for his clients, mostly multinationals operating in China.

“We have worked on cases with clients where there is no absolute proof, but itʼs pretty convincing that something is being manufactured [online to purposely harm a company],” says Flemming. A slew of negative comments from newly registered accounts is one suspicious sign, he says. In Master Kongʼs case, media reports suggested at the time that Tingyi, who controls more than half of Chinaʼs competitive instant noodle market, had gathered material for a complaint against a competitor, but the company didnʼt respond to follow-up questions on the case.

“If it was a competitor, and if itʼs true that Japanese investors control a signifi cant portion of the company, thatʼs a pretty clever way to make a point,” Flemming says. “Iʼm not saying itʼs right, but touching on nationalism is always good for the retweet.”

Pride, Pocketbooks and Poison

Tapping into patriotism is one way to make rumors go viral. Consumers tend to get upset if they believe they receive lower-quality products or services than customers elsewhere. Case in point, when CCTV reported in March that iPhone warranty policies were unfair to Chinaʼs consumers, Apple Inc.ʼs Chief Executive Tim Cook was forced to apologize and pledge improved customer service. Pocketbook issues also come up—amid recent reports that Tencentʼs We-Chat would start charging customers, users voiced anger at potentially paying for something they had been getting for free.

Consumer safety is likely the biggest concern. Thatʼs where most rumors tend to swirl, especially after the 2008 milk powder crisis when at least six children died and thousands fell ill after drinking tainted formula. With customers in a panic, rumors about milk products are constantly popping up, some of them outrageous. In 2010, rumors alleged that Chinaʼs Synutra baby formula had caused three infant girls to develop breasts prematurely. After testing, the government determined the milk was safe, as the company had insisted. Where did the rumors start? With a competitor, some media reported.

Whatever the cause, the damage was vast: in the year ending March 2011, Synutra Internationalʼs sales dropped 15% from the previous year, and it logged a $40.1 million loss. Thatʼs how even a preposterous tale of babies growing breasts can cost a company tens of millions of dollars.

For more on managing reputation attacks see Smeared! How to survive a Smear Campaign