Does it make more sense to ‘beat’ or ‘meet’ your rival’s price?

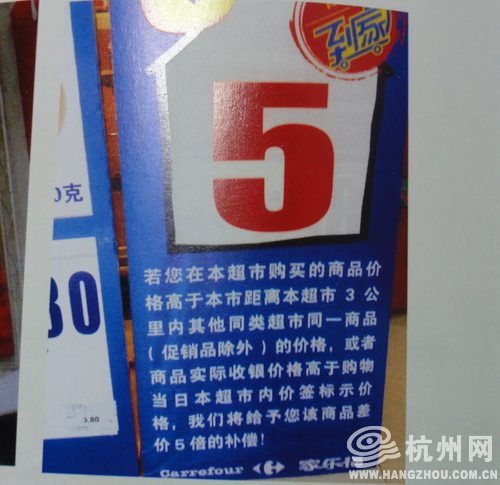

Last time I discussed a price war between China’s largest electronics retailers in which all three promised to price their home appliances below the other two. I explained how such a promise to “beat” any price offered by rivals resulted in a “death spiral” of prices. This time I want to compare this to a strategy that looks similar–one used in China by the retailers Wal-Mart and Carrefour–but has very different results. Wal-Mart is known to post a promise in their stores (see picture from Jinan, Shandong province) to pay customers any difference between their price and a lower price by competitors for the same item. Carrefour has similar postings–such as this one in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province–promising to pay five times the difference.

I am currently in the market for a humidifier so let’s see how these two retailers should set the price of a humidifier and how it will affect me. We can again use game theory and the idea of a “best response” (for a refresher on these concepts see my previous article) to see where Wal-Mart and Carrefour’s promises may lead. To keep things simple, suppose that both firms follow Wal-Mart’s promise to pay the difference between its price and any lower price and that all the potential customers for a humidifier are aware of the retailers’ promises (these simplify the analysis without changing the basic implications).

Begin by assuming you are Carrefour’s pricing manager. If Wal-Mart charges RMB 900 for the humidifier, what is your best response? Broadly you have three choices: you can charge less, the same, or more. Suppose you charge less–perhaps RMB 850. How will Wal-Mart respond? Since it has committed to pay any difference in prices, it will be forced to charge an effective price of RMB 850 as well (its price of RMB 900 minus the RMB 50 penalty). This is the same as Wal-Mart lowering its price to RMB 850.

Suppose instead that you match Wal-Mart’s price. How is it likely to respond? Wal-Mart doesn’t want to lower its price–to say RMB 875. Doing so would force you to lower your effective price to RMB 875 as well (your price of RMB 900 minus the RMB 25 penalty). If Wal-Mart instead maintains their RMB 900 price, then neither firm lowers its price nor pays a penalty.

Let’s compare the two options so far. Both lead to identical prices across the two stores. Either way customers will get divided naturally between the stores based on other aspects such as store proximity and product selection. However, undercutting results in a price of RMB 850 while matching results in a price of RMB 900. Clearly, matching is your better choice. Facing the same decision as you, Wal-Mart’s pricing manager should reach the same conclusion–it is better to match your price than to undercut it.

Unlike the electronics retailers who promised to “beat” any competitor’s price, Wal-Mart and Carrefour have promised to “meet or beat” any price. Adding the extra word “meet” makes all the difference in the world. Promising to beat the competition ties you to a self-destructive path in which you must always undercut your competitors. Allowing for the possibility of meeting your competitor’s price affords you just enough wiggle room to avoid this trap. In fact, it gives both firms an incentive to cooperate.

There is still one possibility I haven’t considered: would you ever want to price your humidifier above Wal-Mart? Possibly. Suppose you raise your price to RMB 925. If Wal-Mart doesn’t respond, then nothing has changed. Your effective price is still RMB 900 because you have to compensate customers the RMB 25 price difference. If, on the other hand, Wal-Mart agrees with you that prices are too low, then it can raise its price to RMB 925. You no longer need to pay the RMB 25 penalty and prices are identical at RMB 925. The result: both of you make more money and you still divide the market based on non-price factors. This is a win-win for you and Wal-Mart. Where does that leave me the customer? Paying a higher price for a humidifier.