The Pitcairn family offers several lessons on how you can sustain a family business across not one, not two, but several generations.

Some people are just born to be entrepreneurs—like John Pitcairn, a Scottish immigrant who landed on US shores in the 1840s at the age of five. Despite the fact that he came from a poor family, he was good at spotting business opportunities—and making the most of them. As a teenager working on the Pennsylvania Railroad, Pitcairn envisioned how land prices would rise due to the railroad. At 17, he took his life’s savings and bought a farm in the countryside—and ended up tripling his money in six months.

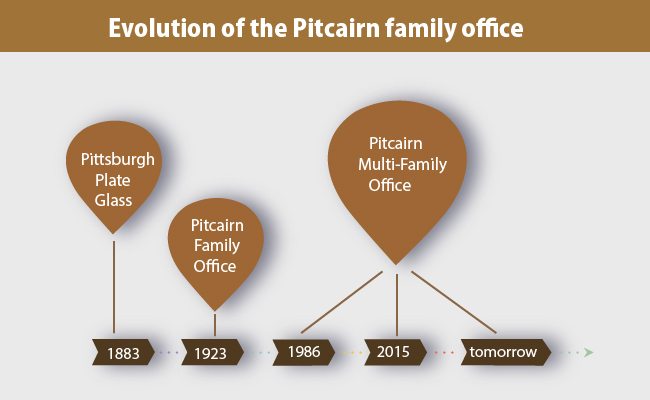

The rest, as they say, is history. He got into oil and gas, and eventually into glass. In 1883, he co-founded the Pittsburgh Plate Glass company (PPG Industries today). Within 10 years of its founding, Pittsburgh Plate Glass represented 65% of all the glass manufactured in the US. He diversified the business of PPG Industries and the family made substantial capital in generation one.

Today the family enterprise of PPG Industries is still going strong. It spans five generations and currently has around 650 family members. “A very important part of the phenomena of sustaining a family enterprise for a hundred years was generation two’s approach of dealing with the complexities of the wealth and their own interests and growing family,” says Dirk Junge, Chairman, Pitcairn Company, the family office.

The three sons of John Pitcairn each had nine children with careers that had nothing to do with PPG. “Their ownership was key, and they could make sure that their ownership interests were well-maintained by sitting on the board and being very influential,” he says.

To make sure that the company functioned smoothly and family interests did no clash with the business, in 1923 they formed one of the first ‘family offices’ in the US: the Pitcairns, the Rockefellers and the Phipps family are considered the three pioneers of this concept in the US.

The family office plays an important role in making sure that the company is well-run and the interests of the family are protected, without mixing business and ownership, which as history shows, is often the deal-breaker. The family office makes sure that the family has a voice in the business. In the Pitcairn case, even the tiniest details are accounted for, such as making sure that the “married-ins” or the spouses of the family members, are taken care of.

It’s a powerful idea, and the Pitcairn example shows how a family office can ensure business longevity.

Over time, the Pitcairn family office became so successful as an “asset manager” and a “tax specialist” that it was turned into a multi-family office, with its services available to other family enterprises as well.

In this interview Junge explains the role of the family office and secrets behind sustaining a business across generations.

Q. Most family businesses don’t last beyond two generations, but yours has flourished over five. How do you manage to keep things together?

A. It’s very typical for a business to be the focus for generation one, and probably generation two, but the family [has to make] a 100-year plan that talks about the changes that it will be encountering as it goes through the generations, the complexity of family and its business being intertwined. Family systems are the strongest when they are compassionate, sharing and caring, when they’re committed to developing the individuals of that family to reach their fullest potential. Family when it’s high-performing, is a loving system; whereas the business has to be financially focused.

The family needs high emotional intelligence to navigate the challenges that it faces, going through generational transitions, and the business needs to understand that it starts out always with an entrepreneur who is very single-minded and driven to take advantage of his insights for how to grow his business. It’s a very autocratic system. Families, when they’re high-performing don’t tend to be autocratic, they tend to be more inclusive, and they benefit from the diversity in the family. But if that sphere takes over the business, then businesses don’t continue to thrive over time. So if a family has a 100-year plan for its enterprises looking at its future, it will embrace the challenges that come up with generational transition.

Also, the family and the business need to be more professionalized to represent the distinction between management and ownership. So what are the systems that allow the boundaries to be clear between family and business, where the very best part about a family enterprise, is the family, and not the very worst part about a family struggling with trying to make sense out of this complex system?

[So] you have the loving-based family system [on one side], and then you have the financial and the logical system [on the other], that’s all about money. And right in the center you have the processes that lend the best practices and best opportunities to deal with this complexity, clarity around governance. Unwritten rules foster distrust. Family enterprises are a relationship business. How do you develop [future] leaders? Are there family leaders in the business? Are there professional leaders/non-family? How does that work? So you’re looking at professionalizing by the time you get to the second generation. And if the family stays stuck with what made it successful in generation one, it doesn’t provide for opportunities, for the voices, ambitions, and the creativity of the next generation, I don’t think it will persist.

Many family businesses or family enterprise don’t get to see the third generation or the fourth or the fifth. One of the only known antidotes to the phenomenon “of shirt sleeves to shirt sleeves in three generations” (a quote often attributed to Andrew Carnegie which means wealth gained in one generation will be lost by the third) is that the family enterprise with its 100-year plan embraces entrepreneurism, the best of what made generation one successful and invites entrepreneurism in all aspects of the succeeding generations.

[pullquote]Unless you have a 100-year plan and are thinking about the future, that will be a volatile cocktail that may blow up the family, and may blow up its enterprise.[/pullquote]It’s a family enterprise, you will have conflict. A lot of people jump to the solution which is conflict resolution, but I think successful families are committed to conflict management which means [conflict] will always be there, it’s who’s stepping up, who’s taking on that issue, and who is being part of the change for the collective whole. You see that 90% of the success of an organization is based on the way it communicates so communication is very important. Governance, leadership, conflict management and communication are some of those keys. Unless you have a 100-year plan and are thinking about the future, that will be a volatile cocktail that may blow up the family, and may blow up its enterprise.

Q. You keep referring to this 100-year plan. We live in a world where we are always talking about the next 2 or 3 years, and the next 100 years is something we can’t even imagine. So how do you work through it?

A. Part of a 100-year plan is being able to understand that there will be change, and the system has to incorporate the diversity that will come from the numbers expanding, but also the ideals and goals. It’s very important particularly for young people to be able to craft their own lives. They benefit from their parents but they have to have their own wings. Their values may be still connected to the legacy values, but it has to be their own values. I’ve seen the benefit when families are committed to this longer-term horizon for them to get very clear about their mission statements. If you don’t have a map of the future, you can end up anywhere. Not so good for achieving sustainability across a generation. So do families spend the time to clarify the individual values, but most importantly the shared values? Is the tent big enough to include different thinking? Are we purposeful about recognizing the difference between business and family? Do we allow for leaders to show up in the family that may never have the competencies or the training or the ability to flourish in the business?

So being purposeful about planning, developing a mission statement for what will be the core values, what will we fight for, what will give us that vision to have a map of the future is really important. So values lead to sustainability of families: what are your system for discovering the new, but holding fast to the old values? Families that are most successful embrace the opportunity to have multiple generations, working through strategic issues together. One of the things that I’ve seen as a real benefit is studying cultures of the past and maybe the future that will help families negotiate the future,…. It’s tribal. [Tribes] always honored the elders; they use storytelling to connect the generations, and that fills up the passion, [creates] the ability for people to manage change. It’s great we have a ceremony that gets repeated on a regular basis in the Pitcairn family system which is committed to honoring the elders, having them tell their stories and captured on video, so it can be preserved for future generations.

Q. How big is the family right now?

A. There are probably more than 650 living descendants from John Pitcairn. One of the other things that allows families to stay together over a long period of time is for them to freely associate. So today maybe about 50% of the families are still owners of the Pitcairn multi-family office where over time other family members have gone their own way. I call that free association. That’s very important for the family because as a collective family, many of us still share this phase, many of us share the same philanthropy interest, and it’s important that the business isn’t the only relationship with this broader family.

Q. Six hundred and fifty people is a lot of voices; a lot of different ways of thinking. How do you bring about consensus, especially when there are different generations involved?

A. I really think that family offices, which had been introduced into this family enterprise concept by the second or third generation, is one of those critical developmental issues that family should take on. But you see the complexities. By the second or third generation, [the business must] assuredly move to a board of directors structure to make the clear distinction between management and ownership. The board of directors are responsible for its strategy, for its negotiation between management and ownership, its ability to invest in the future capital… So if the business has a board of directors, what the family needs is its own version of a board, and that is called a family council.

So by the very nature, a family council can be the sounding board, a collective receptor for the diversification, but can understand its connection with the board of directors to try and deal with those issues that are specifically family and should not be in the boardroom. So I think to be able to have a process in place, it says this is specifically to keep the family communicating constructively doesn’t mean that everybody’s going to sing Kumbaya, but it does mean that the family and its system, the enterprise, is committed to best practices. Family councils allow that.

[pullquote]So I think to be able to have a process in place, it says this is specifically to keep the family communicating constructively doesn’t mean that everybody’s going to sing Kumbaya, but it does mean that the family and its system, the enterprise, is committed to best practices.[/pullquote]At Pitcairn, today we have had more than 70 family members serve on our family council. We have 13 members on our family council and a lot of people say, ‘How do you get on the family council?’ I say, ‘How do you make sure that you have a steady flow of new interested people?’ We have three-year terms, and they are staggered, so we might have four or five positions at any one point of time coming up, and we keep a list and we work it hard to make sure that the broader family understands that they are all invited and at some point they’ll have that opportunity to serve on the family council. The things that I think that are most important to the sustainability of the third, fourth and fifth generation families are that they’ve professionalized, become more democratic and found a way of taking the diversity and making it a strength rather than something that pulls people apart.

Q. How do you ensure enough diversity in the family council at any given point of time? How do people become part of it? Will everyone make it to the family council at some point of time?

A. Our family council has a charter to describe exactly what its purpose is: to improve family-wide communication, to improve the competencies and skills-sets for key leadership that the family enterprise going forward, to develop the capacity within the family system for qualified family directors of the future for the board, for family trustees, and just better inform client owners. Those may all be very important for this family system to negotiate, to navigate the changes that will certainly happen in the future. We had no females in management or on the board or really involved. One of the benefits of my leadership for Pitcairn—I’ve been with Pitcairn for more than 38 years now—is that I improved the role of women at all levels of our family system. So right from the beginning our family council was gender-neutral, and gender-balanced, so it’s an opportunity for me to benefit from the females in our family system, having respect, having a role and once they had been serving in the family council, it allowed the decision-makers, these trustees, to then start having females on our board and we not only have family members, but [female] independent directors as well.

We started with 13 [members in the family council]. It’s good to have an odd number, so that you can have tiebreaks on important decisions. But my view of consensus all starts with the leadership structure, and we practice consensus but we also, as a fallback position, will use democratic voting structures. So the rule of the super-majority will still be held as far as our corporate structure, but shame on me as a chairman of the board if I don’t get our decisions to be consensual.

Q. I would assume that the family council also has multiple generations.

A. Absolutely. First it was focused on the next generation, giving them a platform so that the senior generation could see them stepping up, stepping up their participation, stepping up their contributions. Because it was so successful, the spouses of the uncles came to me and said, ‘We never had this opportunity, we want to be involved.’ And one of the best dynamics we ever had was, we had grandparents, parents and child from the same branch on the family council together. It was spectacular.

Q. Is that fixed that every family council will have a certain number of members from different groups?

A. No, it’s not fixed. It is a very open system, and it evolves over time. Since 1980, we’ve had nine different family council chairs and one of the things that we did do, as part of our governance structure for the business, is we see that the role of family council chair is so critical that by them being elected by their family council, they will have a board seat at the varsity board-level.

Q. What happens if there’s conflict between family council and the board of directors?

A. Then the family enterprise or the family operating business chair, in this case, me, and the family council chair will go into a room and work it out. Now we work very closely together and I am committed because ultimately they do not have a voting power, but they have a tremendous amount of influence. So shame on me as the executive board chair here, if I don’t find a way of taking what I’m hearing and then negotiating: ‘So this is the business board, this is the family council, how can we work together?’ In a few cases where there has been some strategic questioning about our future and our direction coming from the family council, I take it as a direct reflection on me not being able to communicate better to them as shareholders, for them to understand. So we’ve had a few situations where if there is an issue like that, we’re committed to developing white papers for the positions: what was management’s recommendation, how did the board deal with it and what’s its implication for you as an owner. I take the processes that we’ve used at the board for its operating business and then turn around and say, ‘We have this issue, it’s an ownership issue and we probably didn’t do as good a job as we should have done for the operating business to articulate that to our owners.’ So I’d rather hear about it, do something about it, rather than having it fester.

(Watch the video below)

Q. As the family grows, how do the dynamics of the family council change?

A. We were having the complexity of this growing number of family members, and today I think we roughly have 150 adult family members. They’re not all going to be on the family council, they’re not all going to be on the board, and they’re all not going to be part of management of Pitcairn, but they are important. [pullquote]They’re not all going to be on the family council, they’re not all going to be on the board, and they’re all not going to be part of management of Pitcairn, but they are important. [/pullquote]One of the expectations if you are one of the 13 members of the family council is that you will have approximately 10 family members assigned to you, where you must take the deliberations of the board (the family council can come to board meetings, audit the board process), but whatever [pullquote]We were having the complexity of this growing number of family members.[/pullquote]the issue is, whatever we want to communicate, those members of the family council will be provided with outlines and talking points, but they must send an email on a quarterly basis and at least once a year, they must call those 10 and engage them in conversation, so we’re trying to make sure that no one feels left out.

Q. If as a family member, I am not interested in the family business anymore, am I free to walk away?

A. You are.

Q. Is there a process for that?

A. Yes. If you are an owner, and you no longer want to be part of the system, then over time we will find a way of having other family members buy your interest at a very fair price. Fair is very important to relationships, and so we have a very detailed process for determining the value, and we will work with family members so that they have free association. One of the things that makes me happy is, we’ve had some family members who have left, and some are now expressing an interest in coming back. So is your system open and transparent, are the elements of family and business conflicted or are they in fact supporting the family enterprise?