The upcoming Alibaba IPO has brought to the fore the contentious issue of how Chinese companies bypass foreign investment restrictions using a legal structure called the Variable Interest Entity (VIEs).

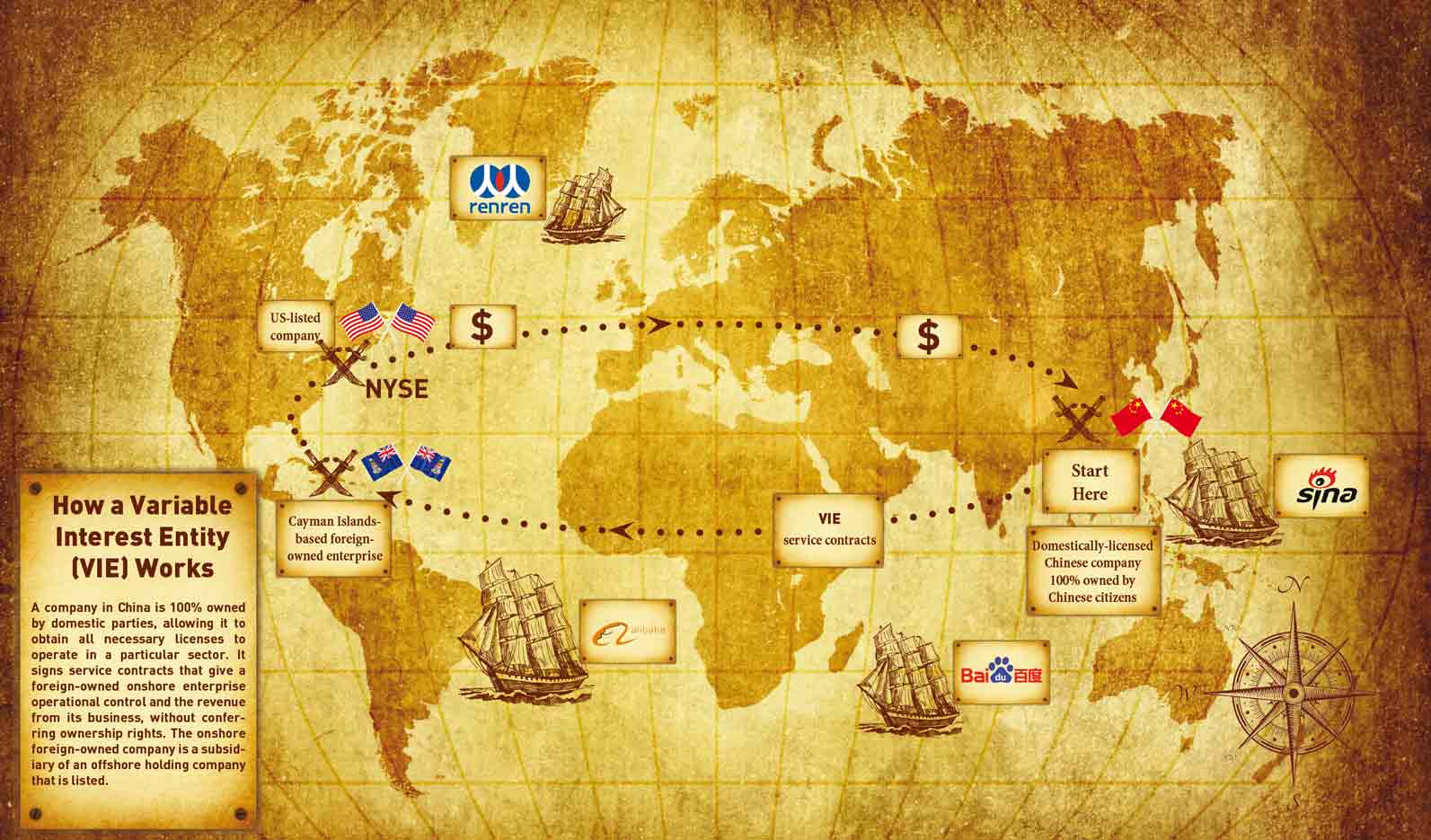

A company in China is 100% owned by domestic parties, allowing it to obtain all necessary licenses to operate in a particular sector. It signs service contracts that give a foreign-owned onshore enterprise operational control and the revenue from its business, without conferring ownership rights. The onshore foreign-owned company is a subsidiary of an offshore holding company that is listed.

When the Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba lists on the New York Stock Exchange in September, it could easily prove to be the biggest initial public offering (IPO) in US history. The floatation is expected to raise anywhere from $15 to $25 billion—potentially surpassing the previous record-holder, Visaʼs $17.9 billion launch in 2007.

The sheer size of Alibabaʼs IPO has drawn attention not only to the company, but also to its underpinning legal structure: a variable interest entity, or VIE. The function of a VIE is to allow Chinese companies to bypass restrictions on foreign investment. This investment structure has been in use for nearly two decades and yet remains obscure to investors who are out of the loop.

“I normally have to ask [investors]: ʻYou know this company is a VIE?ʼ” says Fredrik Öqvist, Beijing-based Founder and CEO of ChinaRAI, a consulting firm that advises mostly European investment funds. “They say, ʻWhat is that, and should I care?ʼ”

While several large companies already listed in the US use VIEs, including Baidu, Sina and Renren, the VIE remains in a legal grey area, still unproven in Chinese courts. Its continued legal haziness may be in part because the Chinese government is reluctant to tamper with one of the few channels that allow Chinese companies to tap foreign capital. Thus in an extreme scenario, Chinese companies could simply walk away with foreign investorsʼ money.

Investors and regulators are watching to see how big Chinese companies like Alibaba play ball with VIEs, keenly aware that their actions could have huge ramifications on both sides of the Pacific.

“These mega-deals may dictate the future of the VIE,” says Drew Bernstein, Co-Managing Partner at the accounting firm Marcum Bernstein & Pinchuk. “If you have one of these mega-deals blow up and the VIE gets put to the test—and it doesnʼt get favorable results—given the amount of money at stake, weʼre talking about deals that would be sizable enough to move governments.” Hence, the Chinese government isnʼt about to mess with a lifeline to foreign capital, even if legal ambiguity is what keeps it flowing.

Like the Real Thing

VIEs were created to circumvent Chinaʼs heavy restrictions on foreign ownership of companies in “sensitive” Chinese industries, among them technology, finance, education and the media. During the late 1990s, the restrictions prevented fast-growing Chinese tech companies from accessing foreign capital, either through public stock markets or private investors such as hedge funds.

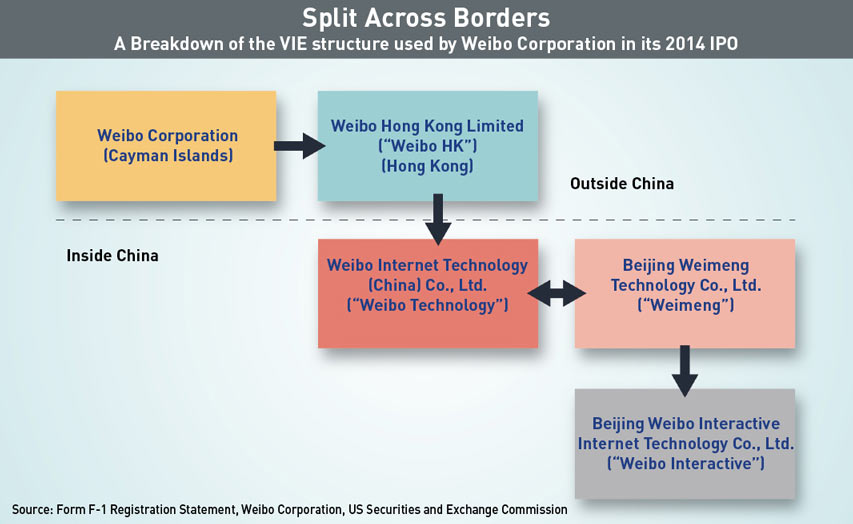

The most basic VIE structure gets around those restrictions by first establishing an offshore holding company—usually based in the Cayman Islands—which will either list on foreign stock markets or be controlled by a private investor. This holding company then establishes a wholly foreign-owned enterprise (WFOE) in China.

While WFOEs can do a lot of business in China, they are foreign-owned and therefore cannot obtain the licenses and permits necessary to operate in sensitive industries. To do that, a mainland Chinese company (or series of companies) is set up, usually owned by local Chinese managers, to hold the licenses, along with enough revenue and assets to pass muster with regulators.

Finally, the WFOE gains de facto control of the mainland company through a slew of legal contracts. These agreements are engineered to mimic actual ownership: the mainland company promises to send part of its revenues and assets to the WFOE, and by extension, the foreign investors.

“Itʼs ownership—not ownership through assets, but ownership through management contracts,” explains Bernstein. “Essentially you donʼt own the company, but you own the equivalent of the economics of the company.”

The first major company to list on American stock markets using the VIE was Chinese internet firm Sina in 2000. The structure has since taken off, and today around half of all Chinese companies listed in the US use VIEs—including every firm that listed in 2014, notes Öqvist. This is impressive growth, especially for a structure that poses so many risks to investors.

Illegal Intentions

The first companies to use VIEs were mostly “asset-light” tech start-ups; as they matured these companies began accumulating valuable land, buildings, brands and intellectual property. In theory, foreign investors own part of these assets.

However, the Chinese government has never explicitly said VIE structures—and specifically the contracts that bind the mainland company to the WFOE—are legitimate. In fact, it may technically be illegal.

Steve Dickinson, a China-based attorney at the law firm Harris Moure, notes that Chinese law contains a clause that deems all contracts “concealing illegal intentions in a lawful form” to be invalid. Because VIEs are designed to bypass laws on foreign ownership, that could void every structure.

With such a weak link underpinning investorsʼ claim on assets, it was perhaps inevitable that the structure would be tested. By coincidence, the first large company to do so was Alibaba.

Over two periods in 2009 and 2010, the companyʼs co-founders, Jack Ma and Simon Xie, quietly transferred Alipay, an online payment system, out of Alibabaʼs WFOE and into a mainland company that they privately controlled. The two argued that Chinese regulators were clamping down on internet finance; only by moving Alipay to a wholly Chinese-owned company could its future be secured.

However, they declined to inform Alibaba ʼs foreign shareholders of the move until 2011. The biggest of these, Yahoo, was livid and publicly lashed out against Ma. At the time, Alipay was thought to be worth around $1.7 billion of Yahooʼs 39% investment in Alibaba.

Ma and Xie quickly settled with Yahoo and another major investor, Softbank of Japan. Among other things, Yahoo would receive 37.5% of Alipayʼs equity if it ever floated on the stock market. Still, the dispute left an enduring mark on Alibabaʼs reputation.

“It will be a question for Alibaba [during its IPO]: how much do people really trust Jack Ma?” says one legal expert who works with investors and Chinese firms. “Heʼs done this before, and with some big shareholders that had big stakes in the company. Whatʼs going to stop him from doing it again?”

The answer is “nothing” in legal terms. But the company has made recent adjustments to its investment structure to build more investor confidence by enlarging the pool of assets from which they could draw returns. In August, Alibaba and Alipayʼs parent company, Small and Micro Financial Services, agreed to lift a $6 billion cap on Alibabaʼs share of the proceeds if Small and Micro goes public or is sold, according to a regulatory filing.

Under the revised agreement, Alibaba will receive 37.5% of the pretax income value of Small and Micro. The Chinese company previously received 49.9% of Alipayʼs pretax income.

But confidence-boosting aside, the fact remains that legally, VIEs are not problem- free solutions to foreign ownership restrictions in China.

Courting Trouble

The original Alipay dispute was never tested in Chinese courts, but other VIE cases have played out to reveal a theme of disapproval checked by a lack of far-reaching implications.

The most significant involved a Hong Kong company called Chinachem. It was one of the first to use a Chinese VIE structure in 1995 when it established a mainland company to acquire a stake in China Minsheng Bank. Two years later, managers at the mainland firm broke contract with Chinachem and asserted that they were the sole legal owners of the Minsheng shares.

After more than a decade of courtroom battles, in 2013 the Supreme Peopleʼs Court ruled that the mainland company, not Chinachem, was the legitimate owner of Minsheng shares. The VIE contracts were designed to illegally circumvent Chinese law and therefore invalid, the court said.

Yet crucially, the court also seemed to recognize the slipperiness of the issue. It demanded the mainland company repay Chinachem its initial investment plus 40% of the value of Minshengʼs current shares and dividends. For a stake worth around $1.26 billion, that was no small sop to investors.

Chinaʼs civil law system is structured in a way that court decisions have no binding legal precedent, giving the Chinachem ruling little other than symbolic significance. Other VIE cases have resulted in similar rulings.

“[The VIE] simply doesnʼt work—I canʼt be more straightforward than that,” says Bernstein. He adds that in all his consulting trips to China over the past 13 years, he “canʼt recall a single incident where foreign shareholders were able to get control of Chinese assets in an adversarial proceeding in which there was a VIE involved.”

Waiting to Pounce

The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the agency charged with protecting American investors, has seemingly joined Chinese courts in frowning upon, but not full-on assaulting, the VIE issue.

“These middle and micro-cap companies that tested the VIE [in Chinese courts], theyʼve never really been important enough to rise to government levels,” says Bernstein. “But if you have a company like Alibaba that decided to essentially void the management contracts, that probably would.”

Around the time of the Alipay dispute the SEC began scrutinizing VIEs.

It has since delivered comment letters to almost all Chinese companies listed in the US, often drilling into their VIE structures. Yet every company has eventually received a sign-off on their operations, suggesting the SEC is looking more to highlight the risks to investors than ban the structure outright.

“The SEC clearly understands the VIE structure: theyʼve asked many, many pointed questions about it, and you can see the [list of] risk factors [in investor documentation] get longer and longer,” says Alan Seem, a Shanghai-based partner at the law firm Shearman & Sterling who has worked on several Chinese IPOs in the US. “But as long as Chinese law firms are willing to opine that the use of VIEs as listing vehicles does not violate Chinese law, and the SEC doesnʼt get a different message from the Chinese government, then I believe theyʼll continue to allow VIE companies to list.”

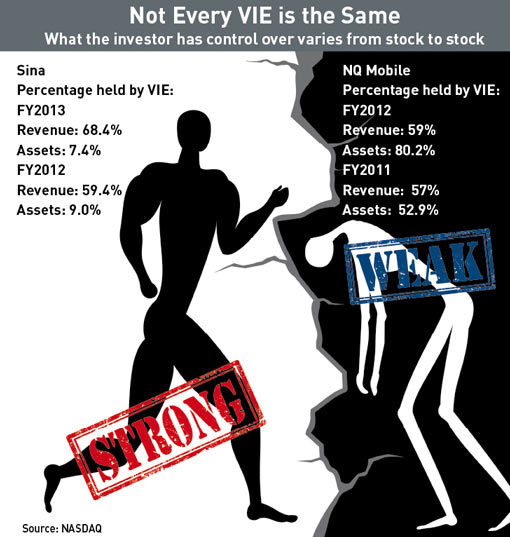

As for investors, they need to understand that not all VIEs carry equal risk, says Öqvist of ChinaRAI. Among other things, his firm researches how much of a companyʼs assets and revenues are held in WFOEs (safer for investors), and how much in mainland companies (less so).

“As long as you have a VIE in which assets in the [mainland company] are below 10%, and all the key intellectual property is in the WFOE, the risk goes down quite significantly,” he says. “Once you start getting up to 20% or 30% of assets, and all the revenue is running through the [mainland company], then you get more worried.” Some say that there is a trend towards “better” VIE structures. Alibaba and JD.com, a Chinese e-commerce company that listed on the NASDAQ in May, are “certainly two of the best VIEs weʼve seen so far,” says Öqvist.

After the Alipay dispute, Alibaba may have come under pressure to restructure its VIE. According to public filings, its current structure places just 7.5% of its assets in mainland companies, compared with 65.5% for New Oriental Education, considered one of the worst VIEs. Öqvist adds that according to its most recent filings, Alibaba has actually run regulatory risks by placing so much of its business in the hands of the WFOE.

Ultimately, many investors view VIEs as simply one risk of many that comes with the territory of investing in Chinese fi rms, says Seem. Much of the decision to invest inevitably comes down to a question of trust.

“Frankly, thatʼs a lot of the reason [investors] go to the [pre-IPO] roadshow, to get a sense of how well they can trust the management team and founders,” says Seem. “Because ultimately if the [Chinese] management decides to go rogue— regardless of whether you have the ability to enforce a legal judgment against them, at that point youʼve already lost.”

A Hot ‘Potato’

For all investorsʼ precautions, the future of the VIE will largely depend on the actions of the Chinese government. Despite the occasional rumor, no government agency has explicitly stated VIEs to be either legal or illegal—a remarkable fact, given its huge scale.

With so much capital riding on the VIE structure, legal experts say regulators are unlikely to suddenly ban VIEs, not least because many Chinese officials have stakes in the listed companies. So why doesnʼt the government simply make VIEs legal? In part, says one analyst, because conservatives in the government are nervous about opening the floodgates to foreign investors in ostensibly protected industries. Another reason is that officials can use the murky status of VIEs to their advantage.

“The fact that [Chinese search engine] Baidu is completely illegal and could be shut down tomorrow means that Baidu is very easy to control by the Chinese government,” says Dickinson. “So the government actually prefers that Baidu is illegal, because they can use the threat to control Baidu.”

Whatʼs striking is how many analysts and legal experts think that until the precise legality of the structure is made clear, some sort of major VIE dispute is bound to erupt—potentially burning investors and sucking in American and Chinese officials.

“In some senses itʼs a hot potato,” says one legal analyst who preferred not to be named. “As long as this all holds together and nobody goes rogue and tries to violate the VIE contracts, then it all works. But if it doesnʼt, then thereʼs a loss of trust and the whole thing falls apart.”