Can Chinese sportswear brand Li-Ning overcome its past mistakes?

In the 2008 Beijing Olympics, legendary Chinese gymnast Li Ning epitomized the image of a powerful, rising China when he soared across the Bird’s Nest in one of the Olympics’ arguably most unforgettable moments. The image of a rising China did not just end there, for here was the leader and namesake of the leading Chinese sportswear brand, capturing global imagination in a moment which vastly outweighed the millions that global competitor Adidas had spent on the event. Ultimately a much smaller Chinese company with a fraction of Adidas’ resources showed just how powerful a Chinese brand could be, a fact not lost on discerning sportswear observers.

Furthermore, Li-Ning the company had managed to consecutively steal top NBA stars like Shaquille O’Neal and Baron Davis from under Nike’s nose, while commandeering a logo that was almost uncomfortably similar to Nike’s famous swoosh. On opening a design center in Nike’s native Portland, Oregon, Li-Ning’s message was heard loud and clear: ‘watch out US brands, we’re here to stay’. The company seemed unstoppable, registering more than 30% growth every year. But its fortunes were to change dramatically. By March 25th of this year, the Chinese sportswear giant was in hot soup, posting losses of nearly RMB 2 billion, its first annual loss since it listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 2004.

News from the ground also paints a picture of a company trying to navigate its way through turbulent waters. State-run China Daily reported in July this year that during the off-season sales in April, stores were selling Li-Ning apparel from two to three years ago at 80% off. The analyst quoted in the article noted that the larger-than-usual size of the discount and the production date of the apparel reflected the seriousness of the company’s inventory problems.

A sportswear analyst, who asked not to be named, also added that most of the franchise owners whom he interviewed this year lamented that they were unable to sell even half of the Li-Ning apparel in their stores last year.

Consider that in 2010, the company’s Chief Marketing Officer Abel Wu said of Nike, “We think we have a respectable competitor from the United States.” In comparison, new Chief Executive Kim Jin-goon told The Wall Street Journal: “I don’t think we’re trying to compete with Nike.” Clearly, the company’s former sky high ambitions have taken a hit.

Days of Glory

Founded in 1990 by Chinese sporting legend and gymnast Li Ning, who won six medals at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, the company benefited from the national adulation of its founder. It also rode the start of the golden decade for the domestic sportswear industry in China. Until 2010, the company enjoyed annual growth of between 30% and 40%.

“It was the first Chinese company making inroads internationally and it was the first Chinese sportswear brand to launch on Hong Kong Stock Exchange,” says Martin Roll, well known brand strategist and author of 2005 book Asian Brand Strategy: How Asia Builds Strong Brands. “It was bold, very hungry, and it wanted to showcase to the world what a Chinese company could become,” he adds.

In 2005, Li-Ning gained ground in international credibility through a strategic joint venture with AIGLE, a French company specializing in handcrafted outdoor sportswear, known for its chic designs and durability. In the same year, Li-Ning signed a strategic alliance with the NBA and became the first Chinese sportswear brand to appear in an NBA basketball court the year after. Upon winning over former Nike collaborators Baron Davis and Shaquille O’Neal, both players pronounced Li-Ning’s designs as the ‘coolest on the court’.

In 2008, Li-Ning signaled its ambitions by quietly planting its flag in Nike headquarters’ backyard, opening its design office in Portland, Oregon where the US headquarters of other major brands Adidas and Columbia Sportswear are located.

That same year Li-Ning stole the show from Adidas with founder Li Ning’s Bird’s Nest stunt at the Olympic Games. The Olympic effect caused the company’s stock to jump by more than 3%, registering an increase of about 54% in profits.

By the time Li-Ning opened its first retail store in the US in February 2010, there was a palpable buzz about the Chinese ‘Nike’. Sneaker fanatics waited in line for five hours to be among the first to own a pair of BD Dooms, basketball shoes named after NBA star Baron Davis.

Making the Change

In July 2010, optimism was in the air when Li-Ning announced its transformation with a new logo and a more upscale product line-up. It also changed its marketing slogan from the tagline ‘anything is possible’ to ‘make the change’, indicating the company’s desire to move away from being seen as piggybacking on Nike’s fame. Its old logo, which bore an uncanny resemblance to Nike’s famous swoosh, was stylized to look more like the Chinese character ‘ren’ (human) as well. Leo Wang, an analyst at China Market Research Group adds that while a logo similar to Nike in the first stage of its development offered the impression that it was of Nike’s standard, being put under the global spotlight at the Olympics probably made Li-Ning more aware of the need for brand positioning.

The company also hiked prices by nearly 10% for shoes and about 20% for clothes to reflect the higher quality of their products, a move that would soon thereafter plague sales figures.

Wang says that the aggressive expansion of distribution channels and sales in 2011 is the main factor in the company’s persistent inventory woes. Li-Ning’s company spokesperson confirmed that in December 2011, the number of stores was at its peak of more than 8,255. In comparison, Nike had about 7,500 shops in China in 2011, while Adidas is estimated to have about 7,800 shops in 2012.

“In 2011, there were a lot of franchises and new distributors because Li-Ning was very optimistic about future sales, which didn’t turn out as expected. Although they had inventory overhang from the Olympics, the main problem comes from 2011,” says Wang.

Within six months, orders for 2011 were rumored to have fallen by 6%. JP Morgan and the like had dumped the company’s shares and Li-Ning had allegedly closed between 500 and 600 stores.

When its revenue fell for the first time in 2011 in comparison to the year before from RMB 1.1 billion to RMB 385 million, the effects of the brand repositioning were evident. Between 2011 and 2012, the company also shuttered 1,821 stores, slightly more than a fifth of its then-network of 8,255 stores.

Course Correction

In January 2012, Li-Ning received a much-needed injection of capital of about $115 million from US private equity firm TPG and Singapore sovereign fund GIC. Following the news, Li-Ning’s shares climbed by more than 10%.

Li-Ning spokesperson Siobhan Zheng highlights several strategies the company is implementing to fix its issues.

Firstly, in July 2012, the company unveiled a transformation plan, with man management changes as the first step. Former Chief Executive Zhang Zhiyong was replaced by TPG executive Kim Jin-goon, who was instrumental in turning around Daphne Holdings, a Chinese women’s shoes retailer. By this year, the company had replaced the five top senior management roles with new hires from companies like Levi Strauss a US-based denim and casual-wear company, and General Mills Taiwan, whose parent company General Mills is a US-based food processing company with a stamp on many of the nation’s most popular snacks.

The TPG arrangement seemed to have boosted Li Ning’s shares by 4%, even after news that Chief Financial Officer Nicholas Chong had resigned in October 2012.

Six months after the plan was unveiled, the company launched a channel revival plan that would focus on buying back inventory to improve the mix of products displayed in stores, weeding out less profitable distributors and working more closely with distributors in general.

Zheng says the core aim of the plan is to transform Li-Ning from a wholesale to a retail business model. She clarifies that “much of the plan involves handholding with distributors and sub-distributors (i.e. distributors who also stock other brands), for instance, helping them do better promotions, store displays and achieving more efficient supply chains to achieve the effect of the retail business model.” For example, the new retail model will include faster product replenishment so that distributors aren’t saddled with unsold products for long periods of time.

Zheng adds that the stores under the pilot project of this retail business model performed significantly better. The only challenge, is the increase in the amount of work since Li-Ning has never implemented such a scheme, she says.

Woes or no, Li-Ning still managed to sign a multi-million dollar contract with NBA star Dwayne Wade, which many analysts highlighted as a bright spot in the company’s current state.

“We chose Wade because he’s not the tallest, and strongest, but he’s gotten to where he is today through sheer hard work. That is a story which resonates with Chinese consumers appreciate a strong work ethic,” Zheng says.

Mixed Responses

While presenting the interim results, Li- Ning told investors that effects of the plans implemented last year had already taken effect, such as better inventory turnover and increased sell-out rates.

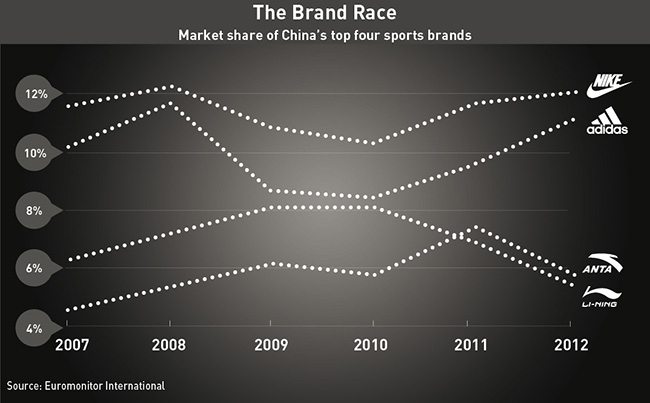

In the meantime, even the world’s largest sporting-goods maker is struggling in China. Eighteen months ago, Nike said in July this year that China sales will fall for the next two quarters, making it five in a row. Li-Ning’s domestic competitors, including ANTA and Peak, reported similar activity.

“The market has been oversupplied for too long. We believe the inventory issues of the industry may not be solved until next year,” says Wei Xiaopo, Head of Consumer Research at CLSA. “When you have a lot of inventory, when everyone is heavily discounting, and when you discount for too much for too long, it damages the brand and that’s hard to restore, especially when Li-Ning’s pricing is a bit higher than its domestic competitors,” he adds.

Other experts like Boston Consulting Group Partner Vincent Lui are more optimistic about Li-Ning’s capacity to turn things around.

Lui suggests that local sports brands are better off zeroing in on their ties to the market in the face of stiff competition from foreign brands. “I think it will be important for local sports brands to be able to connect with the sports heritage in the country, for instance, connecting to sports leagues and college students.”

Lui hit the nail on the head, as Li-Ning’s Zheng emphasizes that “Li-Ning’s major focus is to return to sports, and to focus on China”. Without going into specifics, she revealed that Li-Ning would concentrate more fully on developing a focus on sportswear as opposed to casual wear. Store displays, which use a roughly 70:30 ratio for displaying apparel and sports shoes respectively, will now bring the ratio to 50:50 to reflect the brand’s sharpened focus on sportswear.

But Wang of China Market Research Group notes that casual wear is ‘a market still growing at good speed,’ citing Adidas’ increased sales in China due to their marketing of NEO, a youth-oriented brand in the middle ground between sports and fashion.

Roll also pointed out that Li-Ning’s expansion has only been for less than a decade, while Samsung, another emerging market brand, took almost two decades to become the global brand it is today.

“I think Li-Ning still has the opportunity to create magnitude of unheard proportion, they have the NBA affiliation and that is a fine class of sportswear brands to be in… But they need to get their story right quickly—inventory overhang and consumer perception can kill a company.”