As technology and consumers mature, firms in China are finding that a crisis management strategy is a must-have.

Chinaʼs notoriously tricky business environment is becoming ever tougher, with the past few years having seen companies become engulfed in all sorts of scandals and crises. From false alarms and set-ups to genuine health scares, global names such as McDonaldʼs, KFC, Fonterra, Heinz, Nikon, Apple, Starbucks and Volkswagen, as well as lesser-known local brands, have all found themselves in the crosshairs of Chinese public opinion.

The difficulty of handling a crisis in China is particularly acute for foreign businesses, putting them in a situation where their handling of a scandal at times struggles to replicate the efficient and proper response they could deliver on their home turf. Although certain crisis management ideas might cross borders, China demands its own set of tools and responses—in terms of dealing with its rambunctious social media, increasingly discerning consumers and a powerful government, there is plenty for businesses to get to grips with. Along with exercising due diligence at operational and strategic levels, it is essential that companies come to China with a proactive crisis management strategy in hand.

For those that donʼt, the costs can be severe: McDonaldʼs, rocked by a tainted food scandal in July 2014 after its Chinese supplier was recorded repackaging contaminated meat, saw sales in the Asia, Middle East and Africa region fall 7.3% that month. Meanwhile KFC is still struggling to rebound from a 2012 scandal that found the company peddling chicken with elevated levels of growth hormones, followed by charges that the brandʼs ice cubes were dirtier than toilet water. Clearly, with the rewards of the Chinese market so great and the reaction to any scandal strong and swift, much is at stake. Chinaʼs growing team of crisis specialists have become a vital source of guidance in this treacherous environment.

Damage Limitation

Even the most stellar operators in China arenʼt immune to outbreaks of bad publicity. “I think, number one, I want to say: every single company has the risk of crisis,” says Linda Du, Managing Director of APCO Worldwideʼs Shanghai office. To Du, a specialist in developing corporate communication programs in China for 17 years, crisis prevention is always preferable to managing a scandal thatʼs already broken. “If time and budget allows, Iʼd like to put 80% of the time in crisis prevention instead of crisis management,” she says. “If any issue or problem escalates to a crisis situation, your companyʼs interests and brand have already been damaged.”

To avoid such a scenario, Du suggests companies take an internal audit with management, legal, PR and department heads from across the company to identify different areas that could escalate into crisis. This includes studying the experience of similar companies. “Know your risk,” says Du, and then put your crisis management systems in place. This includes training executives, implementing a media and monitoring alert system and making sure that everyone, from the China teams to staff back at headquarters, knows how to respond.

“Global teams should adopt the crisis management role consistently across the company and know how to alert all of the regional players,” she says. Itʼs also important that the China team knows how to work with the other global players.

If a crisis arises, a quick response is of the essence, even if itʼs simply to acknowledge that an incident has occurred. A common blunder is to jump to conclusions or try to cover up the incident entirely. “Nobody expects you… to know what happened [within a few minutes or within an hour],” Du explains. “But acknowledge thereʼs a problem,” she says. A simple statement that recognizes the issue and promises to follow up with more information demonstrates transparency and control.

“Itʼs good to have a reaction plan in your top drawer,” says Torsten Stocker, a Partner at A.T. Kearney and based in Asia since 1996. This includes anticipating various crisis scenarios, many of which vary by industry. “For a food company, issues with suppliers are obvious,” he says, referring to Chinaʼs infamously fragmented supply chains. Meanwhile, clothing companies should consider what happens if chemicals seep into the product line. “Know who needs to do what, who you need to call,” he says.

“People want to see a company in control, and proactively manage a situation rather than see them avoid communication and try to hide,” says Du.

Consumer Rights Day

Just as some crises can be anticipated, one particular date—Consumer Rights Day, on March 15—carries a particularly high risk of scandal. Riding a rising tide of consumer sentiment, the event is celebrated in China with an annual expose broadcast by the state-owned channel CCTV devoted to publicly shaming companies allegedly short-changing Chinese consumers.

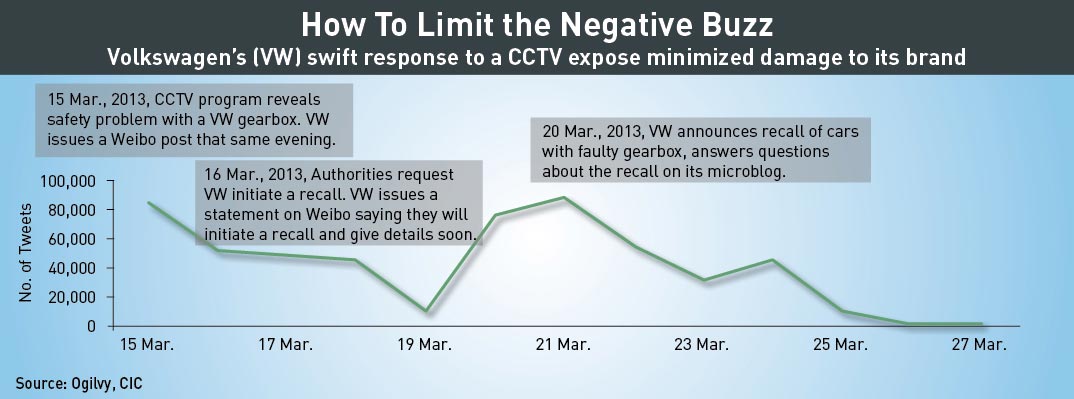

Recent programs have accused McDonaldʼs of repackaging expired meat (the company had faced the same accusation in 2012, along with Carrefour), Volkswagen of selling cars with faulty gearboxes and Nikon of selling cameras with defective lenses. Two years ago, Apple was accused of passing off sub-par warranties and recycled phone parts to Chinese customers.

“The CCTV World Consumer Rights Day broadcast has been around since the nineties but it has definitely become more prominent in the last 4-5 years,” says James Roy, Associate Principal at China Market Research Group in Shanghai.

Du, for one, puts in plenty of prep time on the eve of CCTVʼs annual report, also known as the 3.15 Gala. “We plan a number of scenarios for them,” she says of her clients, describing crisis simulation exercises that account for hypothetical issues with the storefront, the food, employee compliance and various supplier problems. A draft statement, pre-approved by Legal, is ready to be filled in with specifics and pushed out. “You canʼt just sit there and have the print-out guide[s],” says Du, noting that crisis simulation, once unique to high-risk industries like chemicals, has become a new trend among companies in China. “Through exercise, the management team learns a lot.”

Itʼs also important that brands identify a local decision-maker to make the tough calls—“the person who can say, letʼs recall this product, letʼs shut down this store,” says Du. “If you donʼt have a decision-maker in the region, all the good systems, all the good media relations wonʼt work.”

Complicating matters is the complexity of China, where language barriers, the political structure and cultural nuances only add to the time delay. The traditional command- and-control structure—where senior management issues directives from the corporate headquarters, which may be many times zones away—also wastes precious time, compounding the crisis unfolding in the online world and lending additional brand damage.

“You have to empower people on the ground,” says Brian West, Fleishman-Hillardʼs Managing Director of Reputation Management, Asia Pacific. Not only because they are working in real time, but because “local teams understand the social and political nuances of the market theyʼre working in.”

The New Order

Each year CCTVʼs consumer rights program elicits a heated discussion across Chinaʼs online platforms, where millions of increasingly vocal Chinese gather to voice their opinions and frustrations. For the unfortunate stars of the broadcast, this social media chatter sets them scrambling to mitigate brand damage and emerge with their reputations intact.

“Chinese consumers have always followed product safety scandals very closely but social media, especially Sina Weibo (Chinaʼs Twitter), since posts are public and searchable (unlike the more private WeChat), has really amplified a lot of the discussion around brand exposes and focused more attention on programs like the March 15 program,” says Roy.

Companies that find themselves enveloped in scandal as a result of the CCTV gala have found the timeliness of their response makes all the difference. Revelations from the program are quickly reposted, leading to a lively, heated debate over Weibo, in turn generating thousands of comments and re-posts.

When McDonaldʼs was targeted in 2012 over allegedly repackaging expired meat, within an hour the company had posted a sincere apology and promised an investigation and immediate closure of the offending outlet, all the while welcoming government and media supervision. Carrefour offered a similar response after facing the same accusation, but because their statement was posted 30 minutes later than McDonaldʼs, it was accused of being “a follower” and “less sincere”, according to joint research by Ogilvy and CIC.

In this digital landscape where scandals can quickly erupt and go viral, social media confronts brands with risks beyond an annual consumer rights program, but also opportunities.

“The threat of social media is clearly that itʼs a game-changer that one person can ignite the crisis and amplify it around the world,” says West, describing what he calls the “new order of crisis management”. In this new order, speed is of the essence.

“Before we used to talk in terms of the traditional news cycle,” he explains, drawing from three decades of experience in the field. But whereas companies once worked against print publishersʼ daily 3pm deadline, social media has transformed the business landscape so that modern companies donʼt even have that long to respond. “News no longer breaks, it tweets,” he says. “Crises move at the speed of a tweet, and that can mean a thousand of them a second.”

Pointing to 2013 research from the law firm Freshfields, West says that because 28% of crises go global within the first hour, thereʼs no longer such a thing as a local crisis. “But it still takes corporations on average 21 hours to issue a meaningful response,” West explains. And in todayʼs era of instant communications, thatʼs no longer fast enough.

Meanwhile, a misstep can prolong a crisis by days or weeks. In 2012, the 3.15 Gala accused both Volkswagen and Apple of selling defective products. After the report aired, the automaker instantly apologized and soon recalled over 380,000 vehicles with faulty gearboxes, nipping the crisis cycle in the bud after only 24 hours. But Apple, which had been accused of issuing sub-par warranty policies and phones made with recycled parts, initially ignored the report. It was 14 days before Apple finally gave a comprehensive apology and updated its iPhone warranty. By that time, Tim Cook, CEO of Apple, was running full page apologies in Chinese in a desperate effort to restore the brandʼs image.

“Safety issues aside, consumers are increasingly demanding higher levels of service,” says Roy of China Market Research Group. “They want to be respected. The perception that Apple offers different warranty policies in China than it does in the US hurt its image. While thereʼs no surefire way to avoid being at the center of a brand crisis, one thing brands can do is offer the same levels of service in China as in their home markets and around the world that shows respect and is always viewed as a positive by consumers.”

But the opportunities that come with social media include allowing companies to bypass traditional media channels and connect directly with customers. “They can use social media to respond quickly—but also directly—to key stakeholders,” West explains. “They no longer have to rely on traditional media filtering the news or running their side of the story.”

Now companies can post a video of the CEO to their website or channel on a video sharing website, then tweet or blog about it to drive traffic just as people are starting to form opinions about the brand. “You can intervene in that conversation and drive traffic to your website where the facts are,” says West. “Thatʼs really taking control of your destiny and using social media for that ability to communicate direct.” But these digital “newsrooms” are complements, not replacements, to the traditional crisis management structures.

Last fall, when Starbucks was accused by CCTV of charging higher retail prices in China, the company leveraged a variety of media channels to successfully steer the conversation. “They managed it really well through their social media,” says Du, recalling how the Seattle-based retailer took to social media shortly after the CCTV report. There the coffee giant casually pointed to Chinaʼs larger social issues—including pollution, and housing—and poked fun at the broadcaster for using a foreign brand to deflect attention from Chinaʼs more pressing concerns.

“It was kind of casual teasing,” Du says, intended both to shape popular opinion and enlist support. But the companyʼs official statement was very different as it adopted a more polite, courteous tone when addressing the government. In the end, popular opinion tipped in favor of Starbucks, and people chided CCTV for failing to grasp basic market principles.

“Itʼs very interesting to see this company, over the years, how theyʼve learned how to handle crisis in China,” says Du, referring to Starbuckʼs first China crisis back in 2007, when public outrage led the company to shutter a controversial outlet in the Forbidden City in Beijing.

That incident also demonstrates the variety of external risk, on top of the usual operational challenges, faced by companies in China. And if an industry suddenly pops up on the governmentʼs radar, as was the case in a recent string of anti-monopoly cases that targeted foreign auto-makers and IT providers this summer, thereʼs little companies can do. “If thereʼs a drive on the government agenda, then the whole industry will face challenges,” says Du.

West agrees: “Remember whoʼs the boss. Thatʼs the reality youʼve got to deal with. Youʼve got to understand the environment youʼre going into and be sure your business model and everything else stacks up.”

Due Diligence

Avoiding scandal requires regular reviews of policy on the part of companies, says Jeremy Gordon, Director of China Business Services and author of Risky Business in China. “They must also conduct due diligence and testing on the supply chain to ensure that faulty or dangerous materials do not slip in unnoticed.”

The reality that food suppliers are responsible for their supply chain due to being the interface to their customers has burned many multinationals working in China, including KFC and McDonaldʼs. McDonaldʼs latest food scandal, when a major supplier was charged with serious food safety violations, was compounded by that fact the company didnʼt initially realize it was expected to handle the supplierʼs PR crisis. That company, OSI, which is also based in the US, operated under the outdated command-and-control model, rendering them unable to deliver an adequate or timely response.

McDonaldʼs later stepped in try to salvage the damage, but valuable time had been lost and the crisis had already spiraled out of control online.

“China is a fast-moving market, and old assumptions can quickly become outdated,” Gordon says. “It is important to make sure that market research and risk analysis is up-to-date, and specific to the businessʼs needs.” Business intelligence and good relationships (better known in China as “guanxi”) can also help reduce the risk of a crisis occurring in the first place.

But when a crisis does hit, proper preparation can still save the day.

“In our industry, the success is not to lower or shorten the crisis period,” says Du. Rather, the successful cases are the ones nobody ever hears about. “We kill them in our war room.”