Have Chinese consumers lost their appetite for Yum! Brands?

The KFC in the food court at Shanghai’s New World Department store has seen better days. The yellow stuffing of a dingy vinyl booth has broken free of its casing, and someone has patched it with tape. A stool is minus its seat, and faded promotional stickers peel from the backs of chairs.

Customers to this Shanghai shopping center have their pick of almost every major local and foreign food chain, all competing for the Chinese market with new products and trendy store designs. It’s hard to see what might lure them to this shabby outpost of KFC, aside from its reputation as China’s most successful restaurant chain—albeit one whose sales have faltered lately amid questions over the quality of its chicken supply.

Thanks to KFC’s breathtaking expansion in China, a Louisville, Kentucky-based corporation has improbably become China’s largest restaurant company, inspiring case studies in business schools and accolades in books on how to conquer the Chinese market. KFC parent Yum! Brands, a PepsiCo. spin-out that groups KFC with Pizza Hut and Chinese food outlet East Dawning, (which opened 889 new Chinese locations in 2012) and earned 51% of its profits in China, reaching $6.9 billion.

Now KFC is shifting its focus to lower-tier cities, where it says restaurant margins and investment returns are higher. That suggests a de-emphasis of more established cities like Shanghai and Beijing, which is one explanation for the worn appearance of some of its first-tier restaurants. Nonetheless, the sad display projects the image of a company whose best years are behind it—or possibly, of a chain so confident of its success that it is no longer trying so hard to please.

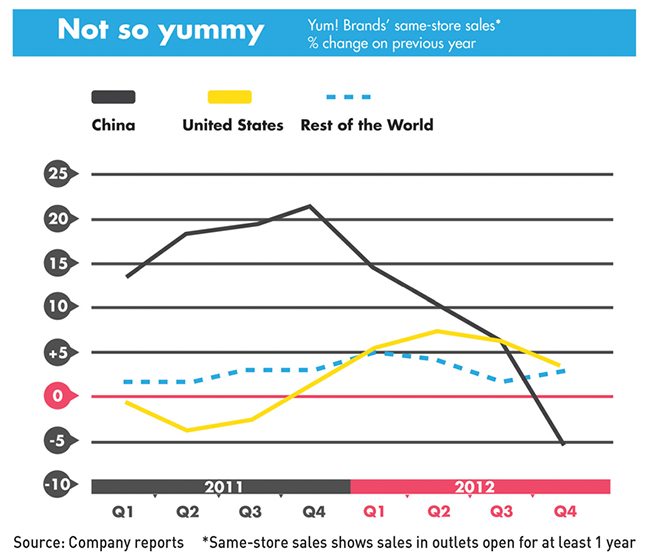

No successful Western company, even one as well-established as Yum!, can ever be too sure of its footing in such a fast-changing, complex market. That lesson became clear in February, when Yum! reported a 6% dip in fourth-quarter same-store sales in China and worse in the first quarter of 2013: a 20% drop.

What exactly went wrong? While a recent scandal over KFC’s chicken supply is the main culprit, new questions are being raised about Yum!, from its strategy to its growing competition in China. Is Yum!’s heady growth in China about to slow down?

Days of Glory

In 2004, 1,000 Yum! employees posed for a photo at the Great Wall to mark the opening of the 1,000th restaurant in China. Clad in puffy red jackets, they raised their arms, transforming their bodies into “Y’s” for Yum! Or possibly a “V” for victory.

The company had opened its first KFC just 17 years before, in 1987, near Tiananmen Square. Soon, grandfatherly brand mascot Colonel Sanders had one of the most recognizable faces in China, alongside that of Chairman Mao.

Warren K. Liu, former VP of Business Development for Yum! predecessor Tricon, and executive accredited with building KFC in China from 1997 to 2001, believes the chain was a natural fit for the Chinese market because people here prefer chicken to the standard US fast food fare of hamburgers.

Beyond that, Liu wrote in KFC in China: Secret Recipe for Success, the company recruited executives from Taiwan—dubbed the “Taiwan Gang”—who understood Chinese sensibilities, resulting in dishes tailored for local tastes, such as Chinese porridge and dough fritters. When KFC entered China it brought a “sweeping revolution,” Liu wrote, noting that both fast food and restaurant chains were new ideas in China.

Yum! now accounts for four out of 10 fast-food restaurants in China, according to a 2012 Euromonitor International report.

China is home to Yum!’s 4,260 KFCs (easily its main cash cow), 826 Pizza Huts (recast as an upscale casual dining spot in China) and more than 450 branches of Little Sheep, a Chinese hotpot restaurant Yum! Brands purchased in 2011. There are also several dozen outlets of East Dawning, a Chinese fast food chain. While small and facing heavy competition from local chains, it may be Yum!’s ultimate mark of self-confidence—a Kentucky-based company selling Chinese food to Chinese people, in China.

No Longer Upwardly Mobile

Back at the New World Department Store’s KFC, four sisters in their 50s and 60s whiled away an afternoon, getting their money’s worth in a promotional deal: Spend RMB 10 and get a free drink or ice cream.

But they didn’t actually eat at KFC. They ate noodles elsewhere, then came to KFC for coffee.

“Even if you don’t buy anything at all at KFC, they still let you sit here,” says Xiaomei Hu, a 65-year-old retired office worker wearing red sneakers and carrying a faux Louis Vuitton handbag.

People are at ease at KFC, to judge from the number of customers napping with their heads down after lunch. But it is no longer an aspirational brand for upwardly mobile Chinese in first-tier cities, says Yifeng Mao, founder of Goldpebble Research, an independent research firm with a focus on China.

“KFC is moving down, while Chinese consumers are moving up,” says Mao, referring to consumers’ increasing wealth and sophistication. Two chains that are aiming to target those increasingly savvy consumers with spending power are Starbucks and Yum!’s Pizza Hut.

Starbucks, which has more than 700 stores here and predicts that China will be its second-biggest market outside the US by 2014, serves espresso and green tea to urban professionals taking time for afternoon chats (takeaway business at Starbucks in China is smaller than in the US, and afternoons, not mornings, are the peak hours).

Yum!’s Pizza Hut, meanwhile, has marketed itself as a stylish place for families and groups to eat standard Western food—not only pizza, which is too cheesy to appeal to some Chinese who avoid dairy—but also easily shared dishes like chicken wings and fried squid. Yum! also has a second Pizza Hut concept in China, a delivery service.

The company is putting a new focus on Pizza Hut openings, since those outlets bring higher margins at a time of rising rents and labor costs. That’s part of the backdrop of Yum!’s recent difficulties, along with higher prices for ingredients, a general slowing of China’s economy, and intensified competition.

China’s Fast-Food Wars

At the McDonald’s next to the worn New World Department store KFC, cheery messages in English plaster freshly painted walls: “Enjoy!” Burger King, meanwhile, has flat-screen TVs and trendy graffiti art scrawled on black walls.

KFC is “stalling out in terms of growth in first-tier markets, so from their point of view it may be thinking, ‘it may not matter if we do as good a job as we did at maintaining the stores we already have,’” says Ben Cavender, Associate Principal of China Market Research Group. “It does send a bad message, because consumers notice.”

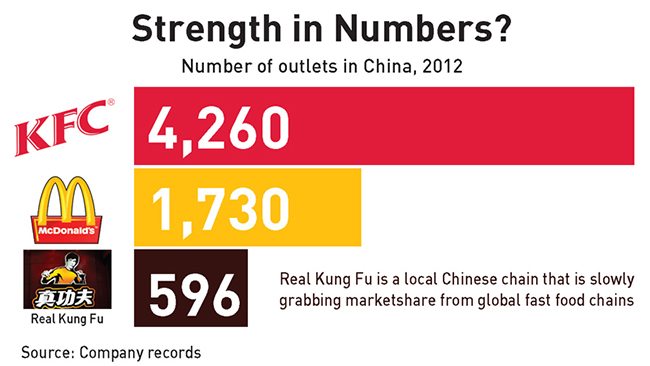

Fresh store design is one area where McDonald’s has been aggressive. It has also launched McCafes, stylish coffee stands, another tactic to keep the brand up-to-date. McDonald’s still has a long way to go to catch up with KFC: It’s the second-biggest fast food brand in China, with a 15.6% share of the market, compared to KFC’s 38.9%, according to Euromonitor. Burger King is still tiny, at 0.4%.

Appearances aren’t everything, of course. KFC “isn’t stylish, but at least it’s clean,” says Hu Ziyi, a 28-year-old Shanghai soda salesman who stopped there recently for a quick chicken burger. Yet the battle over store design is one area in which KFC seems to be resting on its laurels while other Western eateries raise their game to compete not only with each other, but also with growing Chinese brands.

Both KFC and Burger King have lost about 2 percentage points of market share since 2008, according to Euromonitor, while some Chinese brands have made small gains. Chinese fast food chains didn’t exist when KFC entered China, but local entrepreneurs have successfully emulated the Western model, offering fare specifically suited to the Chinese palate.

Real Kung Fu, recognizable for its spunky Bruce Lee logo, is an example. The set menus of its 400-plus stores (up from 300 in 2009) feature steamed meats and vegetables, a healthy alternative to KFC’s fried fare. Japan’s Ajisen noodle shop, Taiwanese fried chicken chain Dicos, which has 1,200 stores after 15 years of operation, and China’s Country Style Cooking Restaurant Chain, a KFC imitator, are also making gains.

Finally, competition for KFC outlets comes from KFC itself, as new stores poach business from existing ones, says Jing Bing, Associate Professor of Marketing at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. In the fourth quarter of 2012, same-store sales dropped, though new outlets opened.

“This is a sign that the increase in the outlets may cannibalize each other,” he says. “The total demand is there, but as you increase the number of stores in an area, the per-store sales decrease.”

That’s a big reason for KFC’s push into other Chinese cities where it still has room to grow.

Crisis Mis-management

China Economic Net reported in November 2012 that some chicken sent to KFC was laced with chemicals. The public was horrified by the science fiction-esque reports of chickens treated to grow to maturity in just 45 days—though KFC retorted that 45 days was an industry norm, and that only 1% of its chicken came from the supplier at the center of the issue.

Since November 2012, when Chinese media accused a KFC supplier of treating its chicken with antiviral drugs to make them grow faster, jokes targeting KFC have popped up on Weibo’s microblogging service. User Bingtuan Tianshan wrote: “Some people ask: Will eating a chicken burger cure the common cold?” After more reports and a probe by Shanghai’s food safety watchdog, Yum! China Chairman and Chief Executive, Sam Su, posted an apology on Weibo, saying the company failed to address the issues quickly enough. But his mea culpa came seven weeks after the first report—an agonizingly slow response in a country on edge about food safety after scandals ranging from deadly baby formula to cooking oil that was collected from gutters and recycled.

The official Chinese news agency, Xinhua, issued a scathing editorial, calling the apology “understated”, accusing the company of “arrogance” and pointing out that Chinese consumers believe foreign brands are “safer and of higher quality than domestic brands,” indicating an abuse of trust. The Shanghai food safety agency declined to bring a case against Yum! but suggested ways to improve its poultry supply chain, which Yum! said it would implement. The company also says it will no longer do business with suppliers that get their chicken from small farms that are hard to keep tabs on. Wu Heng, who runs Throw it out the Window, a widely viewed food safety blog, thinks KFC suffered more than its fair share of blame and still believes it offers the safest chicken option in its price range. But Chinese consumers felt they had been slighted, he says.

“They said that KFC in the US would never have allowed this accident,” says Wu. “They said that KFC has more respect for its American customers.”

KFC has had food safety issues in China before and overcame them. In 2005, it pulled some products amidst a scare over a banned dye. In 2004, it speedily battled fears over bird flu with a Q&A released to journalists and TV commercials emphasizing its high-temperature, germ-killing cooking style. This time, KFC decided to wait until after Chinese New Year to launch a marketing campaign. Yum! says it believes that waiting out a scandal is the best approach.

“We could be wasting a lot of money right now doing marketing,” CEO David Novak told analysts in early February. “We need to give it time.”

Can Yum! Get Its Groove Back?

As questions over KFC’s chicken brewed on social media, Yum!’s stock price dropped about 14% from November 29th 2012 profit warning to its February 4th 2013 quarterly earnings announcement.

While Goldman Sachs downgraded Yum! from “buy” to “neutral” in February, some say Yum!’s current problems and depressed share price provide an opportunity. Janney Capital Markets analyst Mark Kalinowski still has a “buy” rating on Yum!, for example, though he trimmed his fair value estimate by $7 to $68.

Yum! says it can’t predict when the fallout will subside, though it says it is staying the course in China. There is still room for growth: There are 3.5 Yum! restaurants in China for every one million people, compared to 58 in the US, as Goldpebble Research’s Mao points out. But can Yum! continue to grow as fast as in the past? Mao thinks not.

The company plans to open 700 restaurants in China in 2013, down from more than 800 in 2012, he notes. Mao believes future quality issues are inevitable in China. Online shopping is also reducing the foot traffic to malls where many restaurants are located, he says. And KFC, Yum!’s star brand, has simply lost some magic.

Mao recalls going to KFC at Shanghai’s People’s Square more than 20 years ago and waiting in line for an hour. Back then, KFC’s fried chicken was a delicacy to be savored, “not to consume like fast food.”

“As people get richer,” Mao says, “as they move up along the curve, they will notice—it’s just fried chicken.”