With companies like Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent branching out into new areas, China is witnessing the rise of a new breed of digital conglomerates.

Jack Ma’s mix of charm, drive and self-deprecation was on display as he addressed the Economic Club of New York in the Grand Ballroom of the Waldorf Astoria in early June. As club members tucked into a lunch of herb-stuffed chicken breast, mushroom risotto and baby zucchini, the Alibaba founder and Executive Chairman breezed through topics that ranged from his days as an English teacher back in 1988 in Hangzhou to the future of his e-commerce powerhouse.

One name stood out though when Ma listed a handful of American businesses he had learned from while nurturing Alibaba. Microsoft and IBM were unsurprising nominations, but it was the mention of General Electric that caught the eye.

With more than a century separating their respective foundings, the industrial conglomerate and China’s largest online retailer would seem to share little in common. One sells power plants and jet engines, while the other is a mix of businesses resembling Amazon, eBay and PayPal. But as Alibaba expands into new areas, it too is beginning to resemble a conglomerate, and it is not alone.

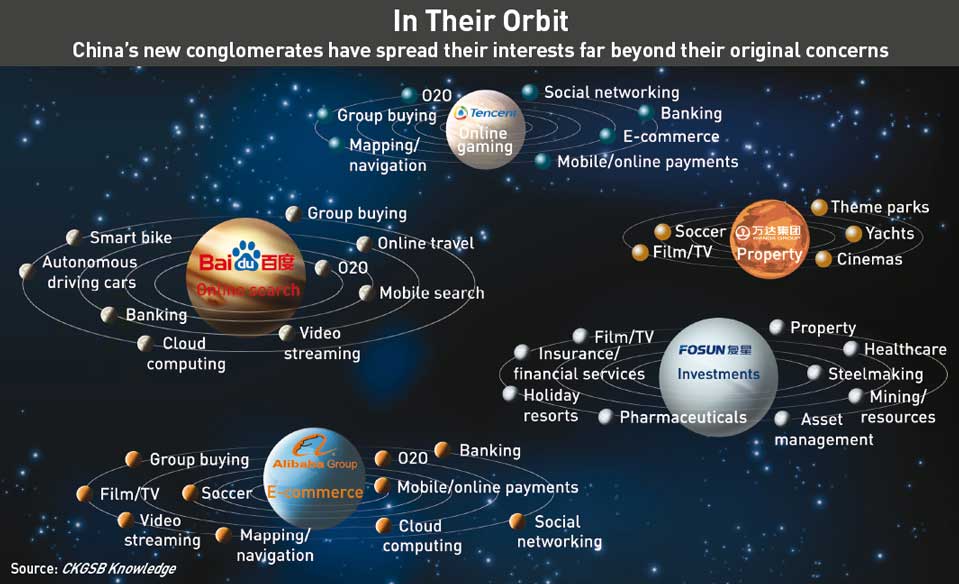

Gone are the days when China’s three biggest internet companies peacefully coexisted in separate domains: Baidu in online search, Alibaba in e-commerce, and Tencent Holdings in social networking services. Now, China’s troika of dotcom titans—BAT for short—are locking horns by using their financial power to muscle into each other’s territories, taking capital stakes and forging business partnerships in aggressive bids to expand beyond their own backyards. They have spread into an at times bewildering array of new sectors, ranging from finance and film production to soccer clubs and gaming.

The three companies’ investment frenzy—estimated by Credit Suisse at $15 billion in one year and 90% of the Chinese total—is aimed at making them an even more central part of Chinese consumers’ digital lives. “It’s all linking back to the fact these guys are platform companies. They move quickly. They’re certainly moving more quickly than their traditional counterparts,” says Michael Clendenin, Managing Director of Shanghai-based RedTech Advisors.

“There’s a lot of hype in China about building a platform, especially among the internet companies,” says Jonathan Zhou, a senior e-commerce and mobile internet analyst for Pacific Epoch, a tech research firm in Shanghai. “They all want to become a so-called platform business. It doesn’t mean all will succeed.”

The explosion of smartphone usage in China with the arrival of the mobile internet has also played a part, according to Duncan Clark, Chairman of consulting firm BDA China and the author of Alibaba: The House That Jack Ma Built, to be published next year.

“BAT are all focused on mobile,” says Clark. “It’s the future—approaching half of Alibaba’s business for example. So this brings them in competition with each other. The former silos in the PC world of e-commerce, search and games no longer apply.”

BAT are leading the charge for diversification but minnows are catching on too. Chinese online entertainment giant LeTV wants to expand into sports, smart cars and cloud computing (and has already launched smartphones and a smartbike), while Xiaomi has already moved beyond the inexpensive smartphones where it made its name to home appliances such as power strips, bedside lamps and air purifiers.

Out of Step?

China’s digital and internet companies are inching towards becoming conglomerates, when such giant sprawling companies went out of fashion in the West decades ago. “I think conglomerates are pretty much out of vogue in the United States and Western economies, but they seem to be the fashion in China,” says Michael Pettis, a professor of finance at Guanghua School of Management at Peking University in Beijing.

They have strong roots in Asia. Ancient family monopolies known as zaibatsu controlled swathes of Imperial Japan’s economy. Today, the likes of Mitsubishi, Mitsui and other post-World War II keiretsu—literally ‘headless combine’—hold similar sway over Japanese industry and represent the country’s traditional business model. South Korea’s economy is dominated by numerous so-called chaebols—family-owned business houses that include household names such as Samsung, LG and Hyundai.

In the decade up to 2010, non-state owned conglomerates in China made up about 40% of the largest 50 companies by revenue, according to McKinsey. In South Korea, where chaebols are deeply embedded in the national psyche, they accounted for 80%. Over the same 10 years, private and independent Chinese conglomerates expanded into 65 new businesses, while Korean companies entered 119 new sectors.

Conglomerates are an integral aspect of Asia’s emerging markets too. In Indonesia, the family-owned Lippo Group has invested in everything from department stores and groceries to internet services and hospitals, while Astra International is a leader in automotives and infrastructure. Thailand’s largest private company, CP Group, does business in agriculture and insurance.

Hulking state firms have long dominated China’s economy, with a tendency to monopolize a single sector, such as energy, banking or railways. But there are also diversified groups both state-owned and independent that are prominent across a range of sectors. State-run CITIC Group is China’s largest conglomerate with holdings in finance, resources and real estate. Then there is privately owned Wanda Group—operating in 10 areas including cinemas, commercial property and theme parks—and Fosun International, China’s largest private conglomerate, which is involved in pharmaceuticals, insurance, steel and real estate.

Both Wanda and Fosun have gone on aggressive spending sprees in recent years to build new, income-generating businesses. Wanda paid $2.6 billion for the AMC cinema chain in 2012 and $1.6 billion for British yacht maker Sunseeker a year later, while Fosun completed its long-running $1.1 billion buyout of France-based resort operator Club Med deal in February, and then in March brought a 5% stake in holiday provider Thomas Cook for $140 million. It has also spent heavily on insurance and banking assets in Germany, Belgium and Portugal—including last year’s $1.5 billion acquisition of Portugal’s largest insurer.

Spreading Their Wings

China’s dotcoms are now emerging as the next generation of conglomerates for the digital age. They have expanded into a broad set of businesses that sometimes have strong linkages to their roots—and are at other times totally unrelated—in an effort to diversify their user base and business model. “The lines between what their core business used to be and what it will be in the future are quickly blurring,” says Clendenin. “In many of these cases, the new areas that they’re pushing into are quite related to their core business.”

“There’s an element of ‘grab it while you can’ going on, both in terms of investing into or buying companies—as we saw with the taxi wars—or in grabbing spaces still left open as a legacy of past inefficiencies in the state sector, like finance, media and perhaps healthcare,” says Clark.

In Alibaba’s case, the e-commerce juggernaut has entered a number of different sectors to grow its operations beyond online shopping. It invested heavily in social media in 2013, by buying popular music-streaming service Xiami and taking an 18% stake in Sina Weibo for $586 million. Notable purchases tangential to e-commerce last year included $1.22 billion in video portal Youku Tudou and $192 million for half of domestic soccer champions Guangzhou Evergrande.

The buying spree has intensified this year. In August, Alibaba announced its biggest deal to date—pumping RMB 28.3 billion ($4.6 billion) into electronics retailer Suning for a 19.99% stake, while Suning will spend up to RMB 14 billion for around 1.1% of Alibaba. The acquisition dwarfs the $590 million Alibaba paid in February for a minority stake in Meizu Technology, a lesser known Chinese smartphone maker.

It has also aggressively offered new financial services around Ant Financial, formerly known as Alipay. The subsidiary clears 80 million online transactions per day, including 45 million transactions through its mobile wallet app—making it the ideal central platform for a plethora of new businesses, including an online bank and credit scoring system launched this summer.

“Getting into finance is a natural extension of what Alibaba already does,” argues Clendenin. He notes understanding a person’s purchasing behavior—what they buy, how much they spend, and how often they do it—can be of key help when deciding whether to offer that person credit or a loan. Alibaba has access to a rich trove of detailed purchase data and user behavior insights collected over years that can be mined for that purpose—which partly explain its investments in ‘big data’ analytics.

“This all goes into trying to model or predict what kind of credit risks they’re going to be,” says Clendenin. “This is the holy grail if you were a provider of loans. They have this sitting in their toolbox, they just haven’t used it properly before.”

Alibaba has taken some flack, however, for a seemingly scattergun approach to investments. Some deals, such as buying into a soccer club, do not make a lot of sense on paper either. That has raised concerns over whether Alibaba risks losing focus by investing in so many disparate sectors at the same time. “Sometimes it seems a little bit like a spaghetti strategy where they are throwing things at the wall and seeing what sticks,” says Clendenin.

Tencent has also stepped into sectors both adjacent and unrelated to its existing activities of social networking and online entertainment. China’s second-biggest internet company has particularly made a number of forays into Alibaba’s turf of e-commerce, with some high-profile investments last year that included $215 million for a 15% stake in e-commerce giant JD. It also took a 20% stake in Dianping, one of China’s most popular listing review and group-buying services site (often called China’s Yelp), for an estimated $1 billion, and injected $700 million in taxi-hailing app Didi Dache.

Dianping and JD were both integrated into WeChat soon after the investments, signaling Tencent’s determination to build an online services platform centered on the messaging service. And like Alibaba, Tencent also has detailed and exploitable data about consumer behavior gathered from its WeChat and QQ services. The information could prove useful for WeBank, the company’s online bank venture—and China’s first private bank—that launched in January.

Baidu has been relatively quieter on its ambitions than its peers. “Baidu’s been the slowest and most conservative out of the three,” says Clendenin. Analysts say the search engine’s aversion to risk and preference for control over invested companies can be detrimental for deal making, as it reduces the pool of potential investments.

Nonetheless, Baidu has stepped up investment to extend its dominance of the search engine market in China into other strategically important sectors such as online travel and video. Clendenin points to the company’s $306 million investment in travel search engine Qunar in 2011 as an example. Baidu’s acquisition of video streaming service PPStream for $370 million in 2013 and ownership of iQiyi, another video portal, are also ultimately about search and helping people find services on the web.

“If you look at iQiyi and PPStream, there’s a certain search element to it in that people go out and search blindly for video titles,” says Clendenin. More recently, it has ploughed money into start-ups operating in niche categories like online education and healthcare delivery.

But Baidu also has projects that are outliers for a search engine. The company’s Beijing Deep Learning Lab raised eyebrows toward the end of last year when it unveiled the DuBike, a so-called ‘smart’ e-bike project loaded with data-generating sensors and regenerative electric tech. Baidu has also worked on wearable tech similar to Google Glass named Baidu Eye and has plans to roll out self-driving cars with BMW later this year. Curious as they are, these research exploration efforts tie into deep learning—an artificial intelligence technique that could help systems such as search engines recognize and process natural or semantic language much better.

Baidu served notice of its ambitions in this promising field last May by hiring renowned deep learning researcher Andrew Ng—a professor of computer science at Stanford and founder of Google’s deep learning efforts—as Chief Scientist and Head of Baidu Research. Not everything has gone according to plan though; earlier this year, a Baidu team was caught cheating in an AI competition that tests how well supercomputers can recognize objects and locations in photos.

Clendenin, however, sees a silver lining to Baidu’s underhanded efforts. “Investing in artificial intelligence is important, and I’m just happy they’re concerned enough about that to try and game the system,” he says. “It shows me that they’re definitely investing in it, that they think it’s important, and that they want to rank internationally. That’s all important when you consider one of the things Chinese companies are often criticized for is not investing enough in their R&D.”

The troika is following in the footsteps of its global peers in diversifying beyond their core competency. Google has undertaken value-chain expansions in recent years—it has reached upstream by building a fiber internet business in the US, and ventured downstream into hardware by selling laptops and smartphones. Amazon’s hugely successful Kindle e-book reader line represents a similar foray into hardware, and away from its primary e-commerce business.

A second driver for China’s new wave of conglomerates is the looming consolidation of large state-owned enterprises (SOEs). China underwent a major round of SOE reform in the late 1990s, with almost 60,000 industrial SOEs closed and 30 million state workers laid off. Now a new round of restructurings is taking place, with the country’s two largest train manufacturers already in the process of merging into a $26 billion global giant. The government is reportedly mulling a raft of similar mergers for industries such as aerospace and defense, shipbuilding, oil and gas, and telecommunications.

Clunking Conglomerates

Conglomerates may be thriving in China and elsewhere in Asia, but they have a checkered past in Western economies. “Generally speaking the history of conglomerates has not been very convincingly in favor of creating value,” says Pettis.

In the case of the US, conglomerates developed on the basis that by expanding into a variety of businesses, a company lowered the risk of bankruptcy as well as the overall cost of capital and all the associated benefits. But Pettis says a major problem is that managers of the different businesses within a conglomerate can sometimes act against the interests of shareholders—the so-called agency problem.

“Managers in a company have a different incentive structure to the owners, so they behave in ways that benefit managers but that don’t necessarily benefit owners,” says Pettis. As managers grew their operation, the more important they would become to the company and the likelier they would receive higher compensation. “All of those things justified the process of becoming a conglomerate from a management point of view.”

From a value creation perspective, however, the managers were unable to efficiently administer very different types of businesses. “They were actually destroying value for their shareholders while increasing value for themselves,” says Pettis.

In terms of wider impact, the support for state firms and resurgence of conglomerates in China also arguably comes at the expense of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in China. Widely considered to be the most vibrant part of the Chinese economy, SMEs contribute around 60% of GDP and accounted for 8% of job creation in 2014. “We really want to be in the process of transferring resources from the large SOEs toward the SMEs,” says Pettis.

Consolidating business power in a handful of companies could potentially stymie competition and slow innovation by throwing up barriers to entry for newcomers. The dominance of a few players could mean an unlevel playing field and would only help those with the right connections, while making success more difficult for start-ups without such connections. Connections will become more critical as the giants solidify their hold on the market.

BAT have leveraged the network effect—when the value of a product to consumers increases as it gets more popular—to drive their main services to greater heights. WeChat and Taobao are prime examples, as their attractiveness increased as more users joined. But Clark warns there is a risk that the benefits of the network effect will ebb over time, either because the companies cannot innovate fast enough or from limits imposed by authorities that fear consumer rights are in danger.

The other managerial problem with conglomerates is that success in one area does not breed it in another. A company that excels at manufacturing cars and marketing them will not necessarily do as well in hotels, and that poses a problem for resource allocation. The sensible move to take would be for the conglomerate to focus on expanding the booming business, while restructuring or even closing down the faltering operation.

But what tends to happen is that resources are shifted from the successful segment to the struggling side. “You never have to make tough decisions because there’s always some part of your empire that is generating cash,” says Pettis.

Not everything BAT touches turns to gold. In some instances, the trio have been guilty of overreach in efforts to build their online empires. Tencent’s forays into e-commerce stand out. While the web giant has had huge success with social media and gaming, it has struggled with the capital-intensive, cutthroat competitive business of e-commerce. Its online retail offerings have struggled, most notably seen with online electronics retailer 51buy. Tencent invested in the start-up in 2011 and took a controlling stake a year later, but quickly discovered it did not have the expertise to be an e-commerce player.

“They tried to scale it over time by pumping a lot of cash into it but then it was bleeding losses,” says Zhou. “The Tencent margin was getting hurt and they realized they weren’t going to be extremely successful in the areas they weren’t proficient in.”

The struggles prompted Tencent to offload its underperforming e-commerce businesses QQ Wanggou and Paipai to JD, while also giving JD a 9.9% stake in 51buy. The move marked a change in strategy for Tencent, with the company shifting the operation and offline heavy lifting of the e-commerce business to a strategic partner with plentiful experience in the market.

“Very smartly, they backed away from it,” says Clendenin. “There was a little bit of overreach but they learned from it. Tencent is usually very good at understanding they might be better off just investing and learning from the particular investee.”

For China’s three internet giants, a fear of missing out on the next big thing is driving their evolution into rival conglomerates. Keeping Jack Ma and his peers up at night is the thought that they might miss a certain trend or hot start-up that enables them to stay relevant and essential to consumers’ lives. With a combined market cap exceeding $450 billion as of mid-July, their race to diversify shows no signs of stopping.

History has shown, however, that conglomerates are susceptible to failure—particularly those in consumer-facing industries. BAT emerged as winners in the highly dynamic and competitive business world of China’s internet, but their gradual conglomeration could see them overtaken by technological changes and upstart companies.