How will vendors adapt as China’s massive smartphone market cools?

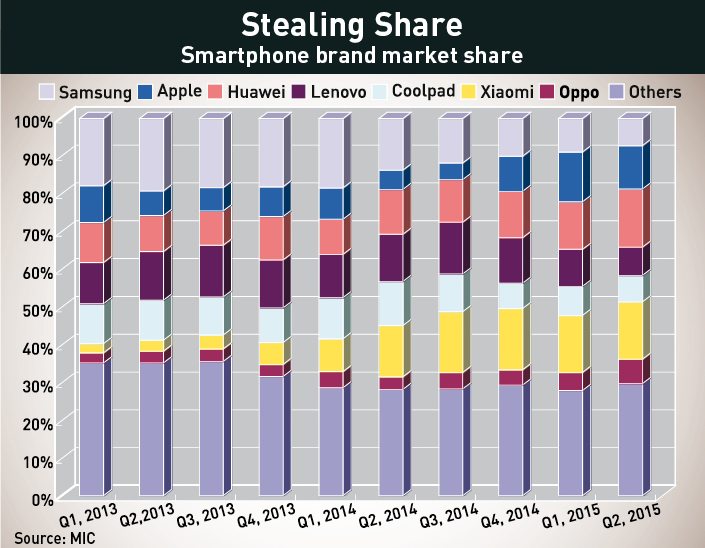

Companies that have spent months being feted by the media don’t tend to revise down their sales target, but in March Chinese smartphone maker Xiaomi did just that—from 100 million units set in December 2014 to 80-100 million. And even that doesn’t truly reflect the company’s ailing growth: rival Chinese brand Huawei overtook Xiaomi in the third quarter as China’s top smartphone vendor.

Analysts are bearish. The Taiwanese research firm TrendForce forecasts Xiaomi will ship 70 million handsets this year. Singapore-based Canalys reckons Xiaomi’s sales fell year-on-year from July to September—the first time the company has experienced such a contraction.

It’s a reality check for the upstart vendor, which soared to fame and a $45 billion valuation in less than five years as China’s first-time smartphone buyers snapped up handsets at a furious rate. From 2012 to 2014, smartphone sales in China doubled, comprising nearly one-third of the global total of 1.27 billion, according to Bernstein Research. By early 2013, mainland China had surpassed the United States to become the world’s largest handset market.

But smartphone sales in China are now flagging. Shipments are forecast to increase just 1.2% on an annual basis this year, down from 19.7% in 2014, according to the research firm IDC.

“The market has reached saturation,” says Nicole Peng, APAC Research Director at Canalys in Shanghai. Cheap Android devices will no longer drive growth as Chinese consumers upgrade to mid-range and high-end handsets, she says.

That augurs ill for companies like Beijing-based Xiaomi and Lenovo, the fifth-largest smartphone brand globally, both of whose growth has been fueled by sales of low-end devices in China. With their home market slowing, they and other Chinese vendors are ramping up overseas expansion from Latin America and Africa to India and Southeast Asia. But in those hotly contested emerging markets Chinese vendors face entrenched local competitors.

At the same time, more Chinese companies are trying their hand at low-end smartphones, buoyed by the Android segment’s low barrier to entry. Alibaba-backed Meizu is one of the top performers among the new wave of Chinese handset vendors. Others, like the video-streaming service LeTV, are using smartphones to promote their other business lines.

One thing is for certain: the world’s largest smartphone market has never been more competitive.

Commoditization Struggles

When smartphone penetration was low in China, it was possible for both upstarts and more established vendors to grow rapidly. But now that the market is flooded with lookalike Android phones, some of the most successful Chinese brands face an unprecedented challenge.

In the case of Xiaomi, the problem is not evident at first glance. After all, the company shipped 17.9 million handsets in the second quarter, up 29.4% year-on-year, according to IDC. Over that same period, Xiaomi’s share of the global smartphone market increased from 4.6% to 5.3%.

The trouble for Xiaomi is that the company is accustomed to growing much faster. “There’s no doubt sales will surpass RMB 100 billion this year, and growth will be more than 50%,” founder and CEO Lei Jun told reporters at China’s National People’s Congress in March.

That’s looking unlikely now. In the first half of the year, Xiaomi sold 34.7 million units, less than half its full-year target.

“Xiaomi’s growth as a smartphone vendor has peaked,” says James Yan, an analyst at IDC in Beijing.

That means the company will need to rethink its strategy of selling cheap handsets in huge volume, says Jade Chang, a smartphone analyst at the Taipei-based Market Intelligence & Consulting Institute (MIC). That business model, with its wafer-thin margins, only works when the market is growing at breakneck speed, she says.

For its part, Lenovo is struggling to manage the acquisition of Motorola. Those travails are hurting Lenovo’s growth, which has already taken a hit from the slowing smartphone market. In the second quarter, the company’s net profit declined 51% from a year earlier to reach $105 million.

In a bid to reduce costs, Lenovo announced in August it would slash its employee headcount of 60,000 by 5%. The company is also restructuring its mobile business group as it aims to streamline its portfolio of smartphone models.

Meanwhile, Samsung is faring even worse. IDC says the South Korean electronics giant remained the top smartphone producer globally in the second quarter. But in China, Samsung tied for fifth place with local brand Oppo. That’s a big drop from two years ago, when Samsung was the top handset maker in China.

“Samsung is still seen as a high-end brand in China, but it doesn’t have a lot of time to reverse its decline,” says Peng of Canalys. “It needs to create a unique experience for users in the growing premium segment.”

It Pays to Go Upmarket

As Chinese consumers discard their Samsung handsets, they are flocking to Apple. The US tech giant has surged in popularity in China since December 2013, when it signed an agreement to sell iPhones through China Mobile, the largest wireless network in the world with over 800 million subscribers. Within a year of the China Mobile deal, Apple rose from China’s No. 6 smartphone vendor to No. 1, surpassing Samsung, Huawei, Lenovo and Xiaomi.

Apple has continued to enjoy brisk China sales this year. In the first quarter, shipments rose 72% from a year earlier, beating iPhone sales in Apple’s home market of the US for the first time, the company said. In the quarter ending June, iPhone sales in China grew 68% year-on-year to 11.9 million units, according to Gartner.

Fu Cong, a Shanghai-based communications consultant, says his wife—a senior manager in a retail bank—loves her iPhone 6 Plus for its functionality and brand cache. “It’s easy to use and everyone knows it’s expensive,” he says. “It’s a status symbol.”

“The segment that Apple targets [in China] is the most lucrative one,” says Teng Bingsheng, Associate Professor of Strategic Management at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business in Beijing. “These people are less sensitive in general to price. As long as Apple continues to introduce good products, I think these people will be rather loyal to Apple.”

Among Android vendors, only Huawei is performing as well as Apple. In fact, in the second quarter, the Shenzhen-based telecom giant did even better, posting 48.1% annual growth—compared with Apple’s 34.9%—as it shipped 29.9 million handsets, IDC says. Those stellar numbers have helped Huawei become the world’s third-largest smartphone maker behind Samsung and Apple.

Huawei’s success derives from its technological advances over the past decade, which have made it capable of producing high-quality mid-range handsets. The company has drawn upon its resources as a telecom giant and invested heavily in research and development (R&D) for smartphone chipsets, says Yan of IDC.

Huawei formerly served as an original equipment manufacturer (OEM), producing handsets for other brands, observes CKGSB’s Teng. “But Huawei realized the value of its own brand would be its most important asset, so it invested a lot more into its own brand name. It is no surprise that is rapidly gaining market share.”

As a result, Huawei now has legions of dedicated fans of its mid-range Honor sub-brand, Yan notes.

Long-Distance Growth

With its massive global network, Huawei is the top-selling Chinese vendor overseas and well positioned to compete in emerging markets, an area other Chinese handset vendors are now tapping in a bid to offset slowing growth at home.

In the developing world, Huawei has a head start on many of its competitors. It entered India in 1999 as a telecom equipment provider and began selling mobile phones to Indian consumers in 2010. In 2013, the telecom giant became the first Chinese brand to produce smartphones in Brazil. By 2014, Huawei was the No. 2 handset vendor behind Samsung in Africa’s market of 1 billion consumers.

Southeast Asian consumers are snapping up Huawei handsets too. The telecom giant forecasts shipment growth there to rise 160% to 8 million units this year on the back of robust demand in Myanmar.

In Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest smartphone market, Oppo is the market leader. For the last four quarters, its handset sales have been the best among the 12 major Chinese smartphone vendors in the country, according to Counterpoint Research. Mid-range smartphones like the R5, which retails for about $450, are Oppo’s best-selling products, the company says.

“Oppo’s smartphones are excellent quality and the company is effective in using localized marketing campaigns to drive sales,” says Yan of IDC.

Southeast Asia, with its geographic proximity to China and cultural similarities, may offer the best opportunities for Chinese smartphone makers, says Chang of MIC. Conversely, the Brazilian market is far away, and the country’s high import duties on smartphones necessitate huge capital investment in production facilities in the country, she says.

In July, Xiaomi made its first foray outside Asia with the Brazil launch of its Redmi 2 handset. Xiaomi will assemble the phones in Brazil, while importing some parts and manufacturing others locally. Yet it is likely that Xiaomi will struggle to keep prices low given the high costs of energy, labor and logistics in Brazil.

Meanwhile, it is in India—the world’s No. 3 smartphone market and its fastest growing—where Chinese vendors are vying most fiercely for market share. India’s fragmented telecom industry, prevalence of retail-driven sales and consumer preference for pre-paid plans make the barrier to entry low in the smartphone market, experts say.

While Huawei enjoys an early mover’s advantage, competition is intensifying fast as vendors move production to the subcontinent to avoid paying higher import taxes: the Indian government recently hiked duties on imported smartphones to attract more local manufacturing.

The number of Chinese smartphone brands sold in India has risen from 12 to 57 since 2013, according to Counterpoint Research. In August, Lenovo announced it would use contract manufacturer Flex’s factory outside of Chennai to produce its Lenovo and Motorola brands. Both Oppo and Vivo have pledged to begin production in India by the end of the year.

Taiwan’s Foxconn Technology Group, the world’s largest contract electronics manufacturer, began producing smartphones in India for Xiaomi and OnePlus this year. Guangdong-based Meizu, which is backed by Alibaba, also plans to cooperate with the Taiwanese original design manufacturer (ODM) to make handsets in India.

A former Foxconn executive, who spoke on condition of anonymity, urges Chinese vendors to proceed cautiously. “We can’t take Foxconn at its word,” the person says. The Taiwanese ODM’s record outside of China is spotty, the person observes, pointing out its Brazil plant plagued by logistics and labor problems, and the massive production facility promised in Indonesia last year that failed to materialize.

The person adds: “India has serious infrastructure and supply chain deficiencies. I’m not sure Foxconn will be able to build a manufacturing facility there that meets its standards.”

Competition in India is also ferocious. The subcontinent has a number of established domestic mobile phone brands like Micromax, Lava, Intex and Karbonn. These brands are well known among Indian consumers and have strong relationships with retail outlets, which could give them an advantage over foreign vendors new to the market, says Ganesh Ramamoorthy, Vice President of Research at Gartner in India.

No Place Like Home

Back in China, the sheer size of the smartphone market means that opportunity remains, but vendors will need to do more to attract the attention of consumers.

Xiaomi is doing that by broadening its product portfolio, observes Helen Chiang, an associate director at IDC in Taipei. The Xiaomi ecosystem is the envy of China’s other Android vendors, she says, noting the company’s foray into television with the Mi TV and Mi set-top box, as well as connected devices beyond smartphones—the Mi Band fitness tracker, a Wi-Fi router-range and an air purifier. The company is even expanding into notebook computers and mobile-operator services.

But Chang is less sanguine about Xiaomi: “Attempts to diversify products and services may dilute what they focused on in the first place and strain resources.”

She continues: “Most importantly, Xiaomi is likely to fall into a fierce patent war,” which could constrain its expansion efforts. Xiaomi’s patent deployment is relatively weak compared to other Chinese brands such as Huawei, she says.

The key for Lenovo regaining its footing in China will be resolving its cultural differences with Motorola, says Peng. “Motorola is focused on product, while Lenovo is successful on supply chain and costs and is not so good on profitability.”

In the short term, “the Motorola brand, which has a good reputation, can be a way for Lenovo to quickly move into the mid and high-range segments in China,” she says. “The Lenovo brand will be used in the lower end.” In the long run, however, Lenovo needs to figure out how to bring its own brand upmarket to ensure sustainable growth, she adds.

Among newer entrants to China’s smartphone market, Meizu is a stand-out, says Yan of IDC. “Their R&D is superb, and now thanks to the big investment from Alibaba [$590 million] they have plenty of cash to use for expansion,” he says.

Some companies in other sectors are adding smartphone business lines, such as paid TV provider LeTV and internet security company Qihoo 360. In the case of LeTV, the company is not aiming to sell handsets in high volume, but to use them to push its core paid TV business, says Peng of Canalys. By contrast, Qihoo is simply aiming to tap the low-cost smartphone market, which remains considerable as millions of Chinese consumers upgrade from older feature phones, market insiders say.

As more brands flood the market with cheap devices, the level of fragmentation will peak in the next year or two, Chang reckons. Companies with small economies of scale who are unable to expand internationally or focus on niche markets [such as tier 5 or tier 6 cities where a large distribution network and marketing budget are not required] will be forced out of the Chinese market during that period, she predicts.

Still, opportunity remains for some aspiring entrants to the low-end market to succeed. Since Xiaomi established the business model of selling cheap handsets largely online, “there is room for a couple of copycats using the same strategy,” says Teng of CKGSB.

“There are a lot of people in China who still have limited income, such as students and retirees,” says Peng. While the low-end market segment will be hyper-competitive, “it will not go away,” she says.