A year on from its debut, we examine the hits and the misses of the Shanghai Free Trade Zone.

The run-up to the launch of the China (Shanghai) Pilot Free Trade Zone (Shanghai Free Trade Zone) was a story of both supply and demand: lots of interest, little detail. By the new zoneʼs debut date of September 29, 2013, excitement had reached fever pitch. Investorsʼ anticipation could be felt, even quantified: the financial press reported that real estate prices near the zone had risen immensely, and that companies with Shanghai in their name had seen their stocks skyrocket by billions of dollars in the months between the zoneʼs July approval by Chinaʼs State Council and its debut.

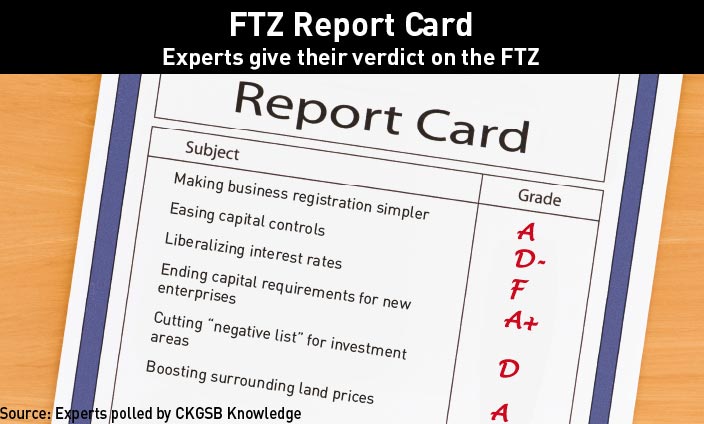

A year on, reception has been mixed. “I think there certainly are people within the government that are disappointed in terms of what has happened with the zone to date,” says Timothy Lamb, Managing Director of Sovereign China, a firm that aids international companies entering China. “I think Li Keqiang in particular expressed his disappointment at the lack of progress.” After six months without much progress from the zone, President Xi Jinping publicly urged Shanghai Free Trade Zone (FTZ) officials to make bold moves, according to a Xinhua report in March.

Despite those misgivings, since its launch the zone has actually been home to some legitimate success stories. Reforms there have removed the registered capital requirements for establishing a new company on the mainland, a move that proved so successful that it was expanded nationwide in March. The State Administration for Industry and Commerce credited that policy change for a boom in new company registration in the period from July to August, which saw 1.5 million new firms and branches open across the mainland.

But a long list of industries off-limits to foreign investors and slow going on promised relaxation of capital controls have dampened enthusiasm among both business interests and reform-minded officials. The recent dismissal of the FTZʼs leader Dai Haibo raised questions about the direction of the zone. However, a ray of hope for the FTZ did come from Chinaʼs President.

Addressing the partyʼs leading group on overall reform in October, Xi said he wanted the lessons learned in the zone—“seeds” of economic reform—to spread throughout the country. “We should plant these seeds in more land so that flowers will blossom and fruits will be harvested as quickly as possible,” Xi told the groupʼs members.

Whatever sprouts will likely hew closer to Chinese officialsʼ standards than those of offshore investors. Zhou Chunsheng, Professor of Finance at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, says that while the zone should be better utilized to facilitate more international trade, he believes that it shouldnʼt be held to the standards established during the pre-launch hype, including assumptions about the list of forbidden industries. That itself constituted a real step forward from a model where everything was assumedly forbidden. “Itʼs not surprising that the list is below the expectations of foreign companies,” Zhou says. “But from Chinaʼs perspective, itʼs good progress.”

Great Expectations

Still, foreign investors were viewed as one of the key stakeholders in the zone, and the initial negative list of 190 items struck many businesses as absurdly large given its stated purpose of minimizing the areas where foreign investment was forbidden. The list covered practically all the areas foreign investors had long been eager to enter. The government trimmed the list to 139 items in July, but it remains a daunting barrier to further foreign investment.

In September a State Council circular revealed that more than 20 extra sectors would be opened up to overseas investors in the FTZ, although logistics-related revisions would have limited impact due to the zoneʼs size. Still, foreign participation in the zone is still just a sliver of the total number of firms registered there: Reuters data shows that in June only 6% of firms were based outside of Greater China.

“People are placing their hopes on a new version of the negative list expected late this year or early next year,” says Howhow Zhang, Head of Research at Z-ben Advisors. He says he has seen great demand for more deregulation from the investment side of the financial industry. “It will be interesting to see whether regulators will respond to those hopes.”

At times, the zone did see greater openness than the rest of the mainland, only to see policy go national. A February notice told FTZ-based businesses they could create a two-way cash pool of RMB, and let individuals at these companies engage in cross-border trade settlement using the yuan. But those measures soon went nationwide after introduction to the zone. From one perspective these could be considered success stories, but they also raise questions about its necessity. A key promise to introduce a market-based interest rate mechanism in the FTZ also remains unfulfilled.

Zhang says that progress was made when Chinaʼs central bank expanded an FTZ policy removing the cap on foreign currency deposit interest rates to greater Shanghai in June. “Itʼs not impossible that banks registered in the FTZ will be given more authority when it comes to what kind of [RMB] deposit rate they can offer to their clients, using it as a trial platform” that can be later expanded, Zhang says. Based on the currency arbitrage that now occurs near the Hong Kong-mainland border, he adds, “Iʼm sure people will find a way to arbitrage from this discrepancy.”

Whatever progress the FTZ made early on was not enough to keep its erstwhile leader, Dai Haibo, above water. His dismissal came just before Li Keqiangʼs visit to mark the FTZʼs anniversary. Dai was supposed to bring to bear his technocratic expertise and the ability to attract foreign investment instead his tenure was dominated by slow progress and widespread investor ennui.

Zhang suggests that slow progress for investment-related business might be exactly what local government regulators wanted. This lack of ground-breaking reform in the zone may indeed be connected to its distance from pro-reform figures in the central government. Han Zheng, Shanghaiʼs party boss, told business magazine Caixin after the FTZʼs launch that the negative list at the time was “the 2013 version… Then we will have the 2014, 2015 and 2016 versions”. This sounded less like Li and Xiʼs pledges and more like the default attitude of Chinese officials: slow and steady.

Whatever caused Daiʼs ouster, it could eventually prove helpful in inculcating an environment more receptive to change—a rarity these days amid an anti-corruption campaign in which officials keep their heads down in all respects, and a macroeconomic environment that would challenge even the steeliest of wills bent on reform.

Measures of Success

The FTZʼs anniversary also marked another turning point. Li-Gang Liu and Hao Zhou, the Chief Economist for Greater China and China Economist at ANZ respectively, wrote that the last-minute launch of an international gold trading board by the Shanghai Gold Exchange, the biggest bullion bourse in the world, was “a milestone initiative of Chinaʼs ambition to push forward RMB internationalization”.

Zhou tells CKGSB Knowledge that while there hadnʼt been significant progress on liberalization beyond this yet, “I think going forward we can expect more from the FTZ for the RMBʼs internationalization.” That has been restricted between the FTZ and offshore market for early on, he and Liu wrote, reflecting Chinaʼs caution toward capital account openness. Officials also plan to open up eight international platforms to trade commodities—oil, gas, iron ore, cotton, liquid chemicals, silver, bulk commodities and non-ferrous metals—by 2015, Xinhua said in an August report.

Xinhua also claimed that the number of businesses operating in the zone over the past year has grown from 8,000 to 20,000. Hao Zhou suggested this likely had multiple causes: first, the initial rush to the zone helped create a cluster effect. Second, registration and administration systems there are much more relaxed than in the rest of the mainland, so the barriers to entry remain low even after other reforms went nationwide. Third, itʼs now easier to find professional talent in the zone.

Shanghaiʼs logistics sector has gotten a boost as well. An October 2013 report from real estate firm CBRE found nearly 90% of the enterprises in the FTZ were related to trade and logistics, with a total of 780,000 square meters of high-quality warehouse space in operation. While vacancy rates then stood at around 20%, CBRE expected the zone to add another 210,000 square meters of warehouse space by 2015. A key benefit of the zone cited by the company was the ability to ship goods there before going through customs, reducing processing time and lowering costs.

Lamb at Sovereign China says other industries that could benefit from the zone include hospitals, which the government has opened up to foreign ownership, and entertainment, another sector available within the zone. While Lamb says that the industries that opened up by cuts to the negative list might not be earth-shattering, he also questioned the emphasis many have placed on foreign investment as the yardstick of the FTZʼs success.

“This is not intended specifically to draw foreign investment. Itʼs essentially a laboratory for the government to try out different reforms,” Lamb says. “And so itʼs really a mistake of seeing this as something thatʼs focused on foreign investment.” A better view on the zone, he adds, was as a way for authorities to tinker with specific policies many view as central to reform— like floating interest rates.

Other Roads to Reform

Economic reform in China tends toward the gradual, making it too early to write off the FTZ just yet. Its national prominence shouldnʼt be overlooked either, with many provinces and cities exploring the idea of opening similar zones, and the examples of policies that have spread across the nation following a trial period in the zone show that the FTZ is playing a role in the thinking of officials across the country.

But that also raises the question of the zoneʼs actual purpose. The precedent of the Qianhai special economic zone remains instructive: officials positioned it as a potential global financial hub that would push forward the yuanʼs internationalization, but it ultimately became isolated thanks to tight regulation. Those measures were born from a fear of arbitrage destabilizing the financial system. Today, as in Qianhai, reforms that take place within Shanghaiʼs own zone canʼt spread to the rest of the country if they stay similarly confined—yet in the areas that are key to the next stage in Chinaʼs financial reforms, it seems some officials are wary of them doing just that.

Economic experiments do not fail or succeed based on immediate results, but they do require a clear purpose and strong leadership. Even Shenzhenʼs Special—and ostensibly export-oriented—Economic Zone, saw an alarming spike in imports following its launch, but ultimately succeeded because of continued support from Deng Xiaoping. Recent supportive remarks from Xi and Li bode well for the Shanghai FTZʼs future, but its biggest reform was a year in the making, and came only with a visit from Chinaʼs premier. If every such success requires a visit from the top leadership, they may look elsewhere for a champion, as they arguably have with Qianhai.