China is now in its fifth straight decade of fast growth. Where is it likely to be at the end of this decade?

There are few stories as dramatic as the rise of China. Ever since the market reform policies kicked in 40-plus years ago, the economy has followed a growth trajectory that other countries can only envy. Over the course of four decades, China has miraculously transformed from an impoverished nation to the world’s second-largest economy.

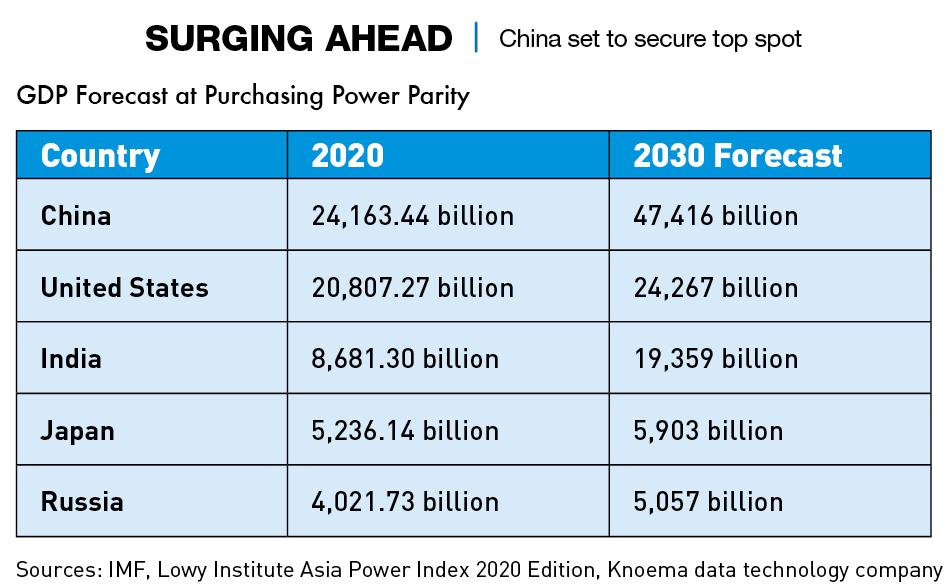

Increasingly, experts project that China will become the world’s biggest economy by as early as 2028—the pandemic has accelerated the progress by at least half a decade compared to most previous estimates. While it makes perfect sense for China’s economy to be the largest given that it has a population of 1.4 billion—more than four times the size of the US—the speed with which the country has caught up is unprecedented.

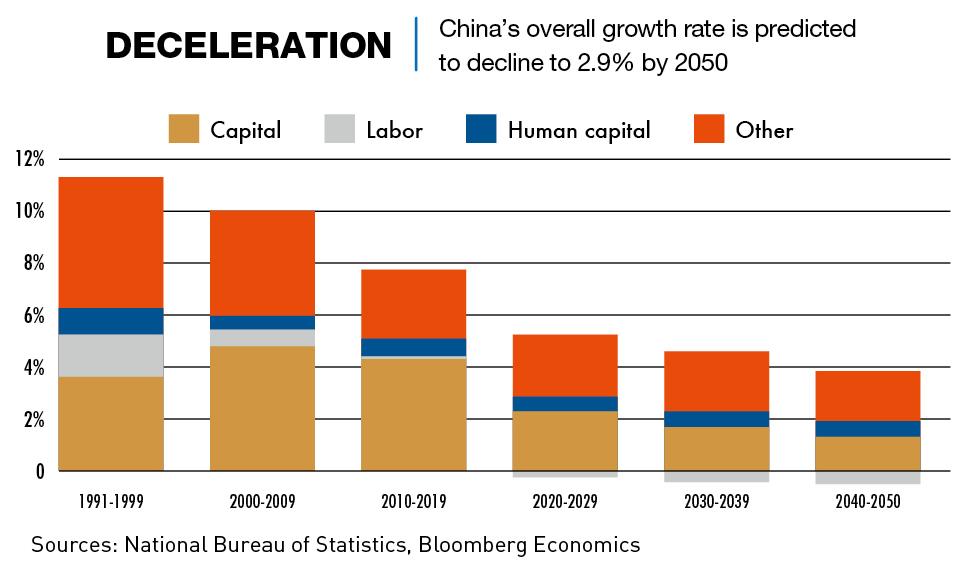

Now the “factory of the world,” the world’s biggest exporter and also the biggest importer of a wide range of commodities, China is looking to the future. Over the next decade, its economy is expected to continue to grow 5.7% per year until 2025, followed by 4.5% annually until 2030, estimates economic consultancy CEBR. Last year, Beijing officially declared that it had beaten poverty, and the urban middle classes now enjoy a prosperity never known before in Chinese history. But the country also faces an array of problems that have the potential to slow its rise.

It is the end of an era in many ways, and the future trajectory is uncharted. “China’s industrialization era is coming to an end,” says CKGSB Finance Professor Zhou Chunsheng. “It’s already an industrialized country, but the economy will keep developing over the next decade. I expect the annual growth rate will be around 5-6% per year. At that pace, China is set to become the largest economy in the world by 2030, surpassing the United States.”

The economic growth rate has been slowing in the past decade, but the country has weathered the COVID-19 crisis far better than any other major economy. It is expected to continue to grow at a fast pace relative to the rest of the world in the decade ahead. Tim Klatte, partner in the forensic advisory services practice of Grant Thornton China, sees strong central control as a factor in that.

“The government has continued to demonstrate that the economy can rebound and provide a sustainable growth trajectory for its people in the face of challenges,” he says. “This speaks to the continued maturity of the decision-makers to manage a crisis well and rebound stronger.”

China’s total gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020 was $15.76 trillion, about 75% of US GDP, but the relative growth rates are dramatically different. Even in virus-hit 2020, the nation achieved a reported GDP rate of 2.3%, while the US economy shrank by 3.5%. “I am confident that China will maintain a stable political and economic environment to reach this goal [of becoming the world’s biggest economy],” Zhou says.

China became the top manufacturer after it acceded to the World Trade Organization in 2001, opening the world to its exports. But at the beginning of the virus crisis, there was much agonizing by foreign companies and countries about the extent to which global supply chains are now dependent upon China. The conclusion since then is largely that there is no easy replacement for the Chinese manufacturing ecosystem.

“China will remain the unchallenged factory of the world over the next decade,” says Ken Jarrett, Senior Advisor at business strategy firm Albright Stonebridge Group. “Even if the US or other countries want to build up their manufacturing capacity, they will likely look at industries of critical national security, such as PPE (personal protective equipment), pharmaceuticals and semiconductors.”

Andrew Polk, Co-founder and Head of Economic Research at Trivium China, a Beijing-based strategic advisory company, agrees that China will remain the world’s factory well beyond this decade. “The conversations around shifting supply chains haven’t been matched with action,” he says. “The disconnect between wanting production to move back home and actually making it happen is huge.”

But China’s dominance in manufacturing is being diluted. Labor costs have escalated, and technical advances are making on-shoring of manufacturing more feasible even as the government itself pushes for production of cheap products to move to other countries.

“There will be some changes to supply chains over the next decade,” says Zhou. “China itself is focusing on transformation and progress. China is known for manufacturing cheap labor-intensive products, but this is no longer the path that the government wants to take. We want to make high-quality, high-tech products, we want to manufacture more value-added products.” The obvious consequence of this is that low-tech manufacturing will to some extent shift to other countries with cheaper labor. “In China, factories and the government will favor intelligent manufacturing,” adds Zhou.

“The pandemic has shown an unhealthy reliance on China,” says Fraser Howie, co-author of Red Capitalism: The Fragile Financial Foundation of China’s Extraordinary Rise. “It’s not that we should stop investing in and working with China, but I don’t want to find myself in a medical emergency and be reliant on China for medical supplies. So, there’s definitely going to be some rebalancing of supply flows, but how significant that’s going to be is still an open question.”

The great decoupling

China’s highly centralized and state-dominated political and economic system is very different from that of other developed economies. These systemic differences and related problems have, in the past few years, raised the specter of a “decoupling” between China and the West, particularly with the US. And while China will remain globally dominant in manufacturing, the prospect of decoupling in terms of other economic ties, such as technology and finance, is very real.

“Decoupling will move forward on both sides, and the Chinese feel that they have to do so for their own protection,” says Jarrett. “But it’s not going to be so extreme that you have a separation of the two economies. We’ll have selective decoupling in fields such as tech and pharmaceuticals.”

The government has been preparing for such a decoupling for a long time and is pushing hard for self-sufficiency. But just how self-sufficient China will be in technology by 2030 is hotly debated. “It’s very possible that China will achieve self-sufficiency in certain technologies by 2030,” says Zhou. “Because the country is spending a great deal on education and R&D. In 2019, China spent more than RMB 2.2 trillion ($340 billion) on R&D, which is the highest in its history. It accounts for more than 2.2% of the GDP and is comparable to what some European countries are spending.”

On the other hand, Howie takes the view that it will be difficult for China to reduce its dependence on foreign sources of materials as much as it would like. “China needs to import oil, food and semiconductors and that is unavoidable,” he says. “The country has been trying to push in these areas for a long time, especially tech, with little success. Pouring a lot of money into tech, as China has been doing, doesn’t automatically make you the world’s leading chip manufacturer because that experience has been built up by engineers over 50 years. Just because I have a cookbook doesn’t make me a Michelin chef.”

“The tech decoupling will continue over the next decade,” adds Polk. “But China will find a way, by hook or by crook, to achieve the self-sustainability that it’s after. They will figure it out enough to muddle through.”

The flows of global trade are also likely to change over the next decade, says Zhang Gang, Assistant Professor of Economics at CKGSB, with an overall reduction in the amount of goods moving from Asia to the West—the dominant trade route of the past two decades. “We can see the growth of trade within East Asia, Europe and North America is faster than the growth of the international trade with other regions, and the pandemic has only accelerated this trend. So, in the future, intra-regional trade is going to be more important that inter-regional trade,” he says.

But Zhang also sees areas where there will be more cooperation during all the changes, including more open markets in China for foreign companies and investment. “We are not only going to share markets with each other, but we are also going to share talent with each other,” he says. “In the past we have exported very smart people to the advanced countries who have studied there and lived there, contributing a lot in terms of technology development. We can do the same within China by welcoming more talent to work for Chinese firms. That is another dimension we can consider in terms of integrating with the global economy.”

The connectors

Decoupling is seen most obviously in the tech world, but China is fast-tracking all aspects of science and technology, including artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things (IoT). The biggest problem it faces in this area is that it lags in production of the most important hardware element of all technical devices—semiconductors, which is dominated by Japan, Taiwan and the US.

The financial connections between China and the rest of the world have also been in the spotlight, and the US has made moves to limit the access of Chinese entities to their financial arena. But China’s own financial markets are growing, and Shanghai and Hong Kong together have become, to some extent, an acceptable alternative to the capital markets of New York and London.

Of particular concern to the government is the fact that the heart of the international financial system is the US dollar while the Chinese currency, the renminbi, remains highly constrained in terms of convertibility. This is unlikely to change by 2030, say most experts.

“The importance of the renminbi will increase only marginally,” says Trivium’s Polk. “And it will take decades before it has the possibility of ever challenging the dollar as a global reserve currency.”

“The global role of the renminbi will only change at the margins over the next 10 years,” adds Howie. “The renminbi is not going to dethrone the dollar or even become a significant player, as long as strict capital controls remain in place. One of the reasons why the US dollar is so widely used is because the US doesn’t care who uses it.”

An uphill climb

In terms of the domestic economy, the new decade is starting with “Dual Circulation.” This policy is based on reducing reliance on exports and increasing the importance of domestic economic activity generally—of China making use of its strengths and moving toward fundamental self-sufficiency.

The fast GDP growth rate of 4.5-5.7%, as projected by CEBR, will include more infrastructure spending, more high-speed rail, faster 5G telecommunications, more cities, roads and and faster 5G telecommunications. More cities, roads and buildings will be part of this economic burst as urbanization rates proceed from 60% last year to a projected 75% in 2030.

“Economic progress and investments in infrastructure are very closely positively correlated,” says Zhou. “For the past decades, China has spent much in building highways, railways and airports, the country’s transportation system is now very advanced. These two mutually support each other. In the future, China will invest in new infrastructure such as 5G, Big Data and IoT. This signals that China has shifted its emphasis of economic development to the digital area.”

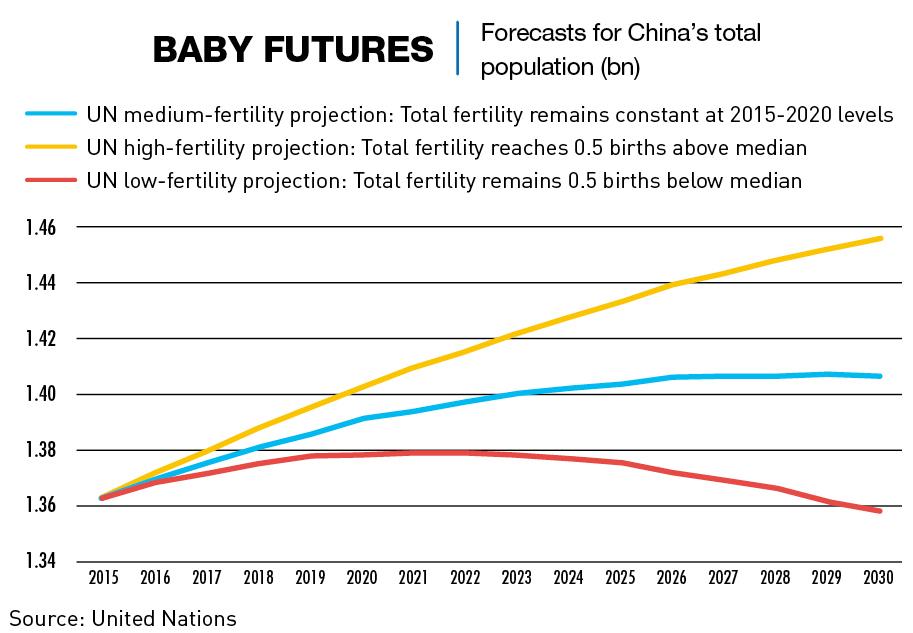

But China is facing a host of problems, some of them inherent to the system, including a rapidly aging population caused by decades of limiting family size to one child (see article pp. 31-35). It has an economic structure that in many ways favors state-owned enterprises over the private economy, and a currency limited in its acceptance globally due to the controls on convertibility.

“There are a lot of economic pressures that China will be facing over the next decade, such as the cost of housing and the ‘996’ (burnout due to working from nine to nine, six days a week) work culture,” says Howie. “This is a stressed populace. The easy years of growth are over and it’s going to be a lot harder on about every level. There are a lot of moving parts to balance, and it doesn’t leave much room for error, especially if you have a world that’s far more cautious and unforgiving of your past misdemeanors.”

Polk agrees that maintaining growth may become difficult as the decade progresses. “China will face challenges regarding rates of productivity,” he says. “It’s become harder for the economy to eke out efficiencies because the gains of the past 20 years were from ‘catch-up growth.’ China had to modernize its economy, but now they’re largely at the technological frontier, making efficiency gains harder.”

Chinese investment around the world, a huge trend in the past 20 years, is also likely to remain subdued as the country focuses more on domestic issues. Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) infrastructure projects in the developing world will continue to be funded by Beijing, but there will probably be fewer than before. “China, as a player on the world stage in terms of investment, is down. Will it stay down? It’s hard to say, it depends on the extent to which China decouples and decides to stick with its current policy which is to keep all of its money at home, except for BRI,” Jarrett says.

The property market is the most important market in China because it impacts the wealth and prosperity of every family. Property values are still rising, especially in the major cities where prices are already high even compared to global cities such as New York and London.

That is not a necessarily a problem because of the impact of financial decoupling, which means that it is hard for Chinese money to leave and buy property elsewhere in the world. Also, there are a huge number of people in China’s rural areas and small towns who would love to buy an apartment in Beijing or Shanghai.

“Appreciation has slowed down a lot,” says Jarrett. “The government will try to control the growth of prices in the coastal megacities, and so you’ll see better growth in the third or fourth-tier cities, but they’ll be quite careful to not allow property prices to slide in any dramatic way because there is too much at stake. We’ll continue to see construction as it’s such a huge component of GDP activity.”

Systemic differences

China is now at the end of what Zhang calls “the golden age of development,” and maintaining growth is both essential for the system, but increasingly difficult to achieve. Trade friction, a demographics challenge, dangerous debt accumulation, strategic challenges, the rich-poor gap, systemic rigidity, lack of transparency—the problems are many.

“China’s economy is facing a more complex world, and the risks confronting it in the external environment are increasing,” says Grant Thornton’s Klatte.

But it is very much in the interests of all players to find a way for China to integrate into the world more fully.

“We hope that China, the European Union and the United States can cooperate in a way that is mutually beneficial for all players,” says Zhou. “The US knows that it’s very difficult for them to stop the development of China’s economy, but they will take some measures to contain the development of China, especially in technology and on the military front. Politics can be hard to predict, and frictions can get in the way, but I believe that cooperation will persist in many different areas.”