Since 1979, the market economy and global free competition has created unprecedented economic development and wealth creation. However, this has also led to massively uneven distribution of income and wealth, a decline in social mobility, and other issues.

Regarding the uneven distribution of income, the United Nations Development Programme’s 2020 report, Human Development Report 2019, revealed that in 1980 the average pre-tax income of the top 10% of US citizens was 11 times greater than that of the bottom 40%. By 2017, this gap had become 27 times bigger. In Europe by 2017, the wealth gap has risen from 10 times greater to 12 times.

According to the World Inequality Database, wealth concentration has become even more pronounced. Between 1980 and 2019, the wealth of the top 1% of the US population rose from 23% to 35%, while the proportion of this group’s income versus the country’s total income increased from 10.5% to 18.8%. During the same period in India, the wealth of the top 1% rose from 7.5% to 21.7%. Between 1980 and 2012, the proportion of the income of this group rose from 12% to 31%.

UN Secretary António Guterres noted in a speech in July 2020 that the 26 richest people in the world own as much wealth as half the global population. Between 1980 and 2016, the world’s richest 1% acquired 27% of the total cumulative growth in income.

Throughout the world, developed countries such as France have experienced relatively large social disruption in recent years and this has also occurred in countries like Chile, which is a member of the OECD. One of the reasons for this is the ever-widening wealth gap and the attendant decline of social mobility.

The amount of disruption brought about by technology, together with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, has exacerbated the already serious income and wealth gaps, highlighting the urgent need to promote inclusiveness and common prosperity within the global sphere.

In the post-COVID-19 era, some technology giants have led and shaped the transformation from an offline economy to online, making them primary beneficiaries of the epidemic. COVID-19 has accelerated this concentration of wealth. According to statistics released by Forbes, the total amount of wealth held by over 2,200 billionaires all over the world rose by USD $1.9 trillion in 2020, an average increase of 20% compared with the end of 2019.

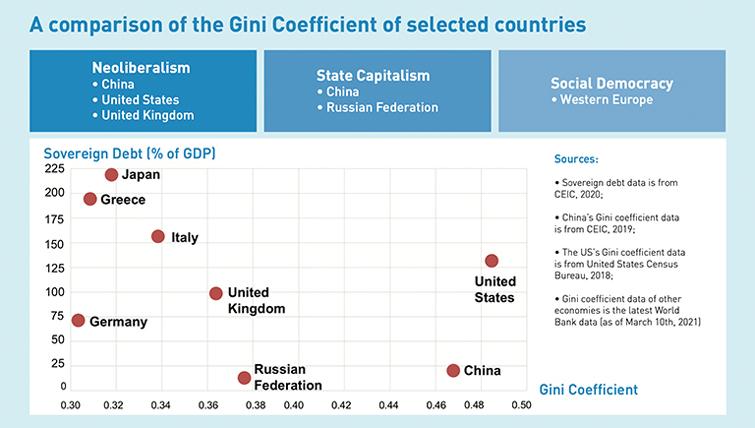

In China, data released by the National Bureau of Statistics shows that the domestic Gini coefficient has been on a downward trend since 2008, although the overall range is still within 0.46–0.47. Globally, 0.4 is considered a warning line for the gap between the rich and the poor. When the Gini coefficient exceeds this figure, economies face the risk that it might trigger serious social instability.

Wealth inequality in China is also among most serious in the world. According to the China Development Report issued by Peking University in 2015, the top 1% of households in China own about one-third of the country’s property.

In response to the unequal distribution of income and wealth, the Fifth Plenary Session of the 19th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China listed “promoting common prosperity” across the country as a very important task of its 14th Five-Year Plan.

President Xi Jinping has emphasized in many speeches that the promotion of common prosperity for the whole nation must be given more importance: “Promoting common prosperity for all people is an arduous, long-term task. It is necessary to select some regions where we can trial this initially [to] demonstrate the results.” The Chinese government recently decided to support the high-quality development in the province of Zhejiang as a model of common prosperity.

China’s promotion of common prosperity is of strategic significance to the stability and long-term development of its economy and social harmony. Its experience in this regard could also demonstrate workable policies for solving the issue of unequal distribution of wealth and income.

Faced with future global changes and the impact of disruptive technology, this article focuses on the issue of how to achieve common prosperity, based on the “Three Distribution” theoretical framework. I will examine and reflect on the experience and lessons learned by different countries and regions from a more global perspective. Further, top-down thinking, the so-called “View the Earth from the Moon”, will, I hope, help to explore possible paths for common prosperity and for building more equitable and inclusive societies.

The First distribution by the invisible hand of the market: economic growth and wealth creation need to become more inclusive and balanced

The first distribution, led by the market mechanism, has a decisive impact on the distribution of income and wealth.

There are many factors that affect income and wealth distribution. These include the political system, the relationship between state and business, whether resource allocation is market-led, industrial policy, the level of education among the population, population demographics, stage of economic development, level of infrastructure development, technological disruption, economic financialization and globalization, anti-monopoly regulations, mechanisms to promote fair competition, and so on.

Chinese and other scholars have done extensive research on the relationship between distribution and inequality of income and wealth, so I will not repeat it here. Instead, I will focus on two changes that may help reduce the income gap caused by the first distribution: enterprise system and corporate value orientation.

In 1997 I proposed the concept of the enterprise system. Based on the degree of separation of ownership and management, companies can be divided into three categories: family type (Type A), modern enterprise system type (Type B), and state-owned type (Type C). Among them, Type B enterprises display the characteristics of the enterprises that have achieved the separation of management and ownership, dispersed equity, and established a modern corporate governance system.

Globally, major developed economies such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Germany, have the enterprise system, which is basically a combination of Type A and Type B companies. A common feature in these developed countries is the important role and presence of a batch of those Type B enterprises that transcend family ownership and control, that separate management and ownership.

In Germany, B-type companies include Siemens, BASF, and Bayer, while in Japan there are Toyota, Honda, Sony, and Panasonic. In East Asia, Japan is the only economy to date that has a significant presence of Type B enterprises.

The United States not only has traditional Type B companies such as IBM, General Electric, General Motors, Citi, Coca-Cola, and Procter & Gamble, but also a new generation of Type B enterprises that has sprung from ground-breaking innovations and has leading and important influence in global development, such as Google, Amazon, and Facebook.

Since its reforms and opening up in 1978, China’s social and economic development has been spectacular. From the perspective of the enterprise system, the current Chinese system represents a combination of Type A and Type C companies.

In China, Type C state-owned enterprises play a dominant role, even a monopolistic role in many industries. At the same time, Type A enterprises have become the backbone of China’s gross domestic product (GDP), employment opportunities, and the creation of new jobs.

In the long term, China may need to spur and cultivate the development of Type B enterprises so as to build an enterprise system that combines Type A, Type B, and Type C companies. This could be a necessary condition for deepening its economic transformation and promoting common prosperity. For a detailed discussion of this issue you can refer to my article, “Enterprise System and its Optimization” published in 2019.

In some countries and regions where Type B companies dominate, the income gap between corporate senior management team, and ordinary employees remains significant after the first distribution. For example, in 2019 the salary of Google CEO Sundar Pichai was about USD $280 million, or 1,085 times the average annual salary of a Google employee of USD $258,000.

According to statistics from Bloomberg in 2018, among listed companies the ratio between the salary of a CEO and the average salary of their employees in the United States was 265:1. The ratio in the United Kingdom was 201:1, in Germany 136:1, and in Japan 58:1. In view of this, narrowing the income gap effectively may require companies to make fundamental shifts in their corporate value orientation.

Globally, there are different orientations in corporate value. The corporate value of “Shareholders First” has been very popular all over the world. Here, the goal of the company is to maximize the interests of shareholders.

Take the United States as an example, where around 6,600 companies had implemented employee stock ownership plans, covering 14 million employees, by 2021. At the same time, corporate high-level management team incentive plans have become the standard. One of the goals is to align the interests of employees, the high-level management team and shareholders, so that employees and high-level management can manage and operate the company more from the interests of shareholders.

In recent years, people from all walks of life in the United States, including business and academia, have reflected on then potential limitations of the value orientation what emphasizes shareholder value maximization.

For example, in 2019 CEOs from 181 US top companies, including Apple and Amazon, jointly signed the “Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation” at Business Roundtable, declaring that creating value for customers, investing in employees, supporting communities, and protecting the environment, plus continuing to protect the interests of shareholders should be a company’s five main value targets. This shows how American business leaders have begun to put more emphasis on their social responsibilities and have more diverse and inclusive value orientations.

The corporate value orientation of Japan differs markedly from that of the US. The two countries have very different cultural traditions. Japanese companies generally prioritize the interests of employees, suppliers, and customers, and only then the interests of shareholders. Further, in Germany, the “Rhine Capitalism” model also pays much attention to the interests of employees, instead of the interests of shareholders only.

The above two corporate value orientations from Japan and Germany contrast with the US type of “Anglo-Saxon capitalism”, being relatively more inclusive and more balanced. The salary ratios of their CEOs and employees also illustrate this point, as noted above, being much smaller.

In the future, the corporate value orientation will still be diverse globally. However, there is no doubt that it will be more balanced, more holistic, more long-term, and more inclusive everywhere, while having more emphasis on social purpose and functions.

In this new era of tectonic global transformations, social conflict is apparent and the expectations of society and government for enterprises’ social functions have reached a new height. This further requires companies to redefine corporate social value propositions from a strategic perspective.

Second distribution (visible hand of government): Social security programs need to become more proactive, more comprehensive, more fair and transparent, and more effective

According to the principle of balancing efficiency and equity, the second distribution led by government is through taxation, social security expenditure, and more, this visible hand attempts to promote equity in societies.

Through the second distribution, the government intends to mitigate the income gap arising from the first distribution, which constitutes an important solution to reducing uneven incomes and wealth.

Countries in the European Union, and especially Nordic countries, are well known for their high-welfare state models. This security system has effectively improved uneven income distribution and maintained good social mobility, helping to achieve more equitable and inclusive economies.

First, I will use the Gini coefficient to compare the impact of the first and second distributions on income inequality in EU and Nordic countries.

Comparing the Gini coefficient after both the first allocation and the second, we can see that the distribution policies in the Nordic countries and some other European countries have significantly reduced uneven income caused by the first distribution.

According to the latest statistics from the OECD, in 2018 the income difference after the first distribution among major Nordic countries was very significant with the Gini coefficient generally above 0.4. Finland even exceeded 0.5. However, after the second distribution, the Gini coefficient of these countries dropped significantly, to within the range 0.26–0.27, which made them the countries with the smallest income gap in the world.

Meanwhile, according to data from the World Bank, the per capita GDP of these Nordic countries maintains a relatively high level. In 2019, Norwegian per capita GDP was around USD $70,000. The per capita GDP of Denmark, Sweden and Finland were all above USD $40,000. These countries are all among the world’s high income countries and have achieved common prosperity. They are the successful examples of European social democracy, which differs from American neoliberalism.

Second, during the five years from 2014 to 2018, the EU’s total social security expenditure and social security expenditure per capita increased steadily. In 2018, the total amount of social security reached EURO €376.6 billion, and the average maximum amount of social security one person could use per year was EURO €8,435. Social security accounted for 28% of GDP. Although there are differences in economic and social development within the EU, overall it has maintained a relatively high level of social security.

Third, fair income distribution can also promote social mobility. According to the World Economic Forum’s 2020 Global Social Mobility Report, the major Nordic countries, including Denmark(1), Norway(2), Finland(3), and Sweden(4), have the highest social mobility ranking in the world. The United States ranks 27th. Among Asian countries, Japan has the best social mobility, ranking 15th. China ranks 45th.

Criticisms of the welfare model have not stopped since its emergence. Critics believe that high welfare encourages people’s laziness and weakens the sense of competition, while increasing the financial burden for society and hindering economic growth.

From the analysis of indicators such as the Gini coefficient, which indicates the gap between the rich and the poor, social security and public finance expenditure, and income per person, European countries, including the Nordic countries plus Germany, and Switzerland, have indeed solved the problem of a high Gini coefficient after the first distribution and effectively promoted social equity and social mobility through a strong, active and comprehensive second distribution system. European countries have accumulated some successful practical experience in promoting social harmony and achieving inclusive growth.

The economic and social development of these European countries is advanced and mature, while China is still a developing country. From this perspective, the situation of other such developing countries as Russia and Brazil is more worthy of reference and benchmarking for China.

Combined social security, education, medical care, and pension expenditure account for a relatively large share of social security in various countries and regions.

China’s public education expenditure accounted for only 3.5% of GDP in 2017, which is lower than the world average of 4.5%. It not only has a large gap of more than 6% compared with the Nordic countries, but also is lower than Brazil (6.3%), Russia (4.7%), and India (3.8%).

In health care, China’s expenditure accounted for 5.2% of GDP in 2017, which was lower than Brazil (9.5%) and Russia (5.3%), and higher than India (3.5 %). By the end of 2019, more than 1.35 billion Chinese people had basic medical insurance, with a participation rate of over 95%. However, medical expenditure per person was relatively low. According to data from the World Health Organization, in 2017, China’s expenditure (USD $841 per capita, per annum) was not only much lower than that of the United States (USD $10,246 dollars), but also lower than Brazil (USD $1,424) and Russia (USD $1,404).

Regarding old age security, according to the OECD statistics, between 2015 and 2016, Brazil and Russia’s pension expenditure accounted for around 9.1% of GDP, which was even higher than some developed countries such as the US (4.9%). China’s pension expenditure accounted for 4.1% of its GDP.

These statistics show that, at this stage, there is still much room for China to increase its investment in social security programs. Especially when compared with developing countries with a similar GDP per capita, such as Brazil or Russia, China lags behind in education, medical care, pensions, unemployment benefits and spending.

In recent years, the Chinese government has attached great importance to common prosperity. In the 14th Five-Year Plan, it was proposed to improve the redistribution mechanism and increase the accuracy of adjustments on taxation, social security, and transfer payment.

In the future, we need to have a stronger and more proactive second distribution, build a more comprehensive and equitable social security system that enables the results of reform and developments to benefit all people and achieve common prosperity.

Some of the successful experiences and failures of some European high-welfare countries and some of the practices in BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India and China) are worthy of reference.

Third distribution: Cultivate the culture of donation and charity, and promote social innovation

The third distribution is to use some of the personal and institutional wealth for public welfare, and for social purpose on the basis of individual volition.

The US is remarkable for the spirit of fraternity and generosity embodied in its donations and charity culture, and the influence of various charitable organizations on its society. Charitable donations and non-governmental charitable organizations have made an important contribution to the relief of the wealth gap after the first and second distribution in the US.

According to the 2020 US Charitable Donations Report, released by Giving USA Foundation in June 2020, the total amount of charitable donations in the US in 2019 was around USD $449.64 billion, accounting for 2.1% of GDP. After allowing for inflation, this ranked second highest in its domestic history.

Personal donations are the largest source of charitable donations in the US. In 2019 these accounted for about 68.87 % of donations, totaling USD $309.7 billion, followed by donations from foundations totaling approximately USD $75.7 billion. Legacy donations totaled approximately USD $43.2 billion and corporate donations amounted to approximately USD $ 21.1 billion.

In the US, charitable donations have become a general consensus across strata with 70–90% of American families donating every year. Each family donates an average USD $2,500 per year, which is two to 20 times that of European families.

In 2019, China received a total of RMB 170.144 billion (USD $26.45 billion) in domestic and foreign donations, of which the mainland received a total of RMB 150.944 billion, accounting for 0.15% of its GDP. The largest source of donations was enterprises (61.71%), followed by individuals (26.40%), social organizations (5.75%), public institutions and religious sites (2.49%), government ministries (1.67%), groups and organizations (0.21%), and others (1.77%).

The gap between China and the US is obvious. US GDP is about 1.45 times that of China, while the total amount of US charitable donations is about 20 times greater.

According to The Philanthropy 50 list in Chronicle of Philanthropy in the US, in 2020 the top 50 philanthropists donated a total of USD $24.7 billion, compared with USD $15.8 billion in 2019, an increase of 56%. Such donations were mainly for various projects for climate change, epidemic prevention and control, poverty relief and education.

Andrew Carnegie brought to the American entrepreneur and businessman the concept that it is shameful to die with wealth. Bill Gates and Warren Buffett initiated the Donation Commitment in 2010, advocating that billionaires and billionaires across the US donate half of their wealth to charities. According to statistics from Forbes, to the end of January 2021, the top 25 richest Americans have donated a total amount of USD $149 billion in their lifetimes.

In the future, the solution to the problems of income and wealth inequality and diminishing social mobility will not be achieved by individual action from governments, enterprises, non-governmental organizations, or international organizations. The goal of common prosperity requires the cooperation, coordinated and joint undertaking of governments, enterprises, non-governmental organizations, civil society, and international organizations, through the social innovation of consolidating all these resources and players.

The road to common prosperity

Looking at the development of major economies in the world over the past 40 years, China and the US have led the world in economic development and wealth growth. These two countries, despite their outstanding economic performances, have also experienced very serious problems of uneven income and uneven distribution of wealth. In 2019, the Gini coefficient was 0.48 in the US and 0.46 in China ranked 3rd and 4th among world’s major economies only after Brazil (0.53) and India (0.50).

How can the aforementioned observations and reflections bring lights to China’s future path to common prosperity?

First, China needs to maintain and strengthen its sustained and strong economic growth in the first distribution, in particular relying on innovation and value competition rather than price competition, to create more high-value-added employment opportunities, and to continue to sustain a new generation of economic disruptions. The reasoning behind this is that growth and continuous wealth creation are prerequisites for common prosperity.

Future economic development and growth must also be more inclusive and balanced, another necessary condition for common prosperity. China must optimize its enterprise system and focus more on building more Type B enterprises.

In terms of corporate value orientation, Chinese companies need to be more holistic, more inclusive, more balanced, and go beyond the concept of maximizing shareholders’ interests. Chinese companies should also pay more attention to corporate social values and purpose, actively participate in promoting social innovation, and become a backbone for solving social problems.

Social values and purposes in the new era have become an indispensable part of strategy for many large-scale corporates. The superimposed influence of technological disruption, the COVID-19 pandemic and other factors have intensified the issue of income and wealth inequality.

Second, in the future, more active, transparent, and equitable redistribution of wealth thorough the visible hand of government are needed around the world. From this point of view, the rise of “socialism” globally may be one of the big megatrends of the new era.

Building a more complete, comprehensive, equitable social security system is a necessary condition for achieving common prosperity. At the moment, China and the EU countries are not at the same stage of development, and thus a high-welfare society is not entirely suitable for China’s current situation. However, the EU’s successful experiences with the second distribution, including its failures and lessons, are still worthy of reference. Developing countries such as Russia and Brazil have similar per capita GDP to China, which compared with them also has room for improving education, medical care, and pensions. In the future, China needs to increase investment to construct a more active, stronger, and fairer second distribution system.

Third, regarding the third distribution, the US example offers some lessons. The US may have the most advanced market economy, unsurpassed innovation capabilities and unmatched generosity in giving, charity and philanthropy, but the US is not viewed as a good example of common prosperity. The US case illustrates the critical role of the visible hand by government for common prosperity and highlights potential limitations of combining the invisible hand the third redistribution for common prosperity. For the future, the third hand, social innovation which goes beyond charity and philanthropy, will become complementary to the invisible hand of market and the visible hand of government, and may play a more important role for reaching common prosperity.

For common prosperity, China needs to learn from many economies around the globe and to be innovative in explore new paths to building a more equitable, sustainable and inclusive society. Exploration and innovation in common prosperity by China is not only of great significance to the country’s economic development and prosperity, social harmony and advancement. It could also help contribute Chinese wisdom and solutions to the important challenges of human development worldwide.

Xiang Bing is Professor of China Business and Globalization and the founding Dean of the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (CKGSB).