On July 10, 2025, the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM) released the latest data on the country’s automobile production, sales and exports:

In the first half of 2025, China produced 15.62 million vehicles and sold 15.65 million—up 12.5% and 11.4% year-on-year, respectively. Among them, new energy vehicle (NEV) production and sales totaled nearly 7 million units, rising over 40% year-on-year and accounting for 44.3% of all new car sales. Exports of all vehicles reached 3.08 million units—NEVs made up over one-third of that figure, with a 75.2% surge compared to the same period last year.

Despite economic headwinds, China’s automotive industry—particularly its electric vehicle segment—is proving remarkably resilient.

Since the beginning of this year, debates over fierce internal competition among Chinese NEV companies have intensified. While continuing to compete domestically, these automakers are also increasingly venturing abroad—into Europe, the Asia-Pacific, South America, and beyond. Thanks to strong performance, innovative features, and competitive pricing, Chinese NEVs are earning recognition in these international markets.

However, the U.S. continues to impose high tariffs and market restrictions on Chinese NEVs, attributing their rise largely to government subsidies.

But is the Chinese EV boom really just about subsidies?

A Look at the Numbers

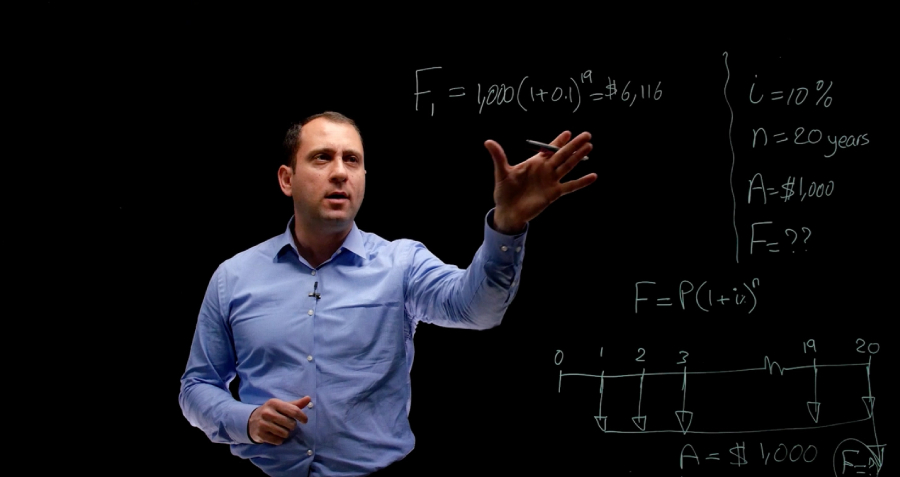

According to figures released by China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, between 2010—when China’s NEV policy framework began—and the end of 2022, the central government spent over 152.1 billion yuan (about $21 billion) in NEV subsidies, supporting around 3.17 million vehicles. In comparison, in 2024 alone, Chinese EV giant BYD invested 54.2 billion yuan (about $7.5 billion) in R&D. Over the past 14 years, BYD’s total R&D spending has exceeded 180 billion yuan.

That’s just one company. The cumulative R&D investments by all Chinese EV makers likely dwarf government contributions many times over.

Therefore, attributing the rise of China’s new energy vehicles primarily to government subsidies does not hold up.

Some may still argue that local governments in China have provided substantial subsidies to NEV companies. While it’s true that local governments have offered incentives to local automakers, the overall amounts were relatively limited, often paid in instalments over several years. In some cases, fiscally strained local governments have even failed to fulfill promised subsidies for years—a fact that can be verified through the financial reports of listed automakers.

Overall, given the significant debt pressure facing many local governments, large-scale, sustained subsidies are not a viable long-term strategy.

The timeline of China’s NEV rise also supports this point. As the industry matured, subsidies were progressively reduced in phases. The most substantial reduction occurred in 2019, when most local subsidies were eliminated, and national-level subsidies were cut by more than 50% compared to 2018. Yet, it was precisely in 2019 that China’s NEV industry reached a turning point. Following a “knockout round” of market consolidation, the industry has experienced rapid growth since 2020.

In 2019, China’s NEV production and sales stood at just 1.242 million and 1.206 million units, respectively. By 2024, those figures had surged to 12.888 million and 12.866 million units. Based on data from the first half of 2025, it’s likely that this year will break the previous record.

So, what is the real driving force behind this rapid rise?

It boils down to two key factors:

- The introduction of a competitive ecosystem for companies; and

- Intergovernmental competition paired with tax incentives for businesses.

Let’s examine each in turn.

1. A Competitive Ecosystem of Private Innovators

For decades, China’s auto industry was tightly regulated, primarily controlled through the approval of production licenses, especially passenger cars. It wasn’t until 2001 that Geely became the first private firm allowed to produce passenger cars, breaking the monopoly of state-owned and joint-venture manufacturers.

In 2003, BYD—then primarily a battery manufacturer—entered the automotive industry by acquiring Qinchuan Auto, a defunct military vehicle firm with a passenger car production license. Through its commitment to R&D and its battery expertise, BYD became a pioneer in self-developed NEV technology, laying the foundation for China’s broader EV push.

In 2007, NEVs were officially listed as a “priority industry” by China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), unlocking a wave of private investment. Then in 2014, a flood of new players emerged—many from the tech world—benefiting from Tesla’s patent sharing, technological breakthroughs by Chinese companies like CATL and BYD in battery, electric motor and electronic control, and a wave of supportive policies. These included NIO, XPeng, Li Auto, WM Motor, Leapmotor, Neta, Qiantu, Byton, and others.

This surge in entrepreneurial activity prompted fierce market competition and innovation—often described in China as the “catfish effect,” wherein disruptive players force the incumbents to adapt or fail.

Meanwhile, Tesla’s Shanghai Gigafactory, enabled by the 2018 removal of foreign ownership limits in the NEV space, added even more dynamism to the market.

2. Intergovernmental Competition and Strategic Tax Relief

Local governments, long eager to attract investment and boost GDP, view the EV sector as a prized opportunity. NEVs bring not just jobs and tax revenue, but also a robust industrial chain with downstream economic benefits. In fact, local governments have historically shown enthusiasm for car manufacturing, competing to earn the title of “China’s top automotive city.”

After China elevated the NEV industry to one of national priority in 2012, local governments became increasingly eager to cultivate and attract NEV companies. Cities like Shenzhen—with little legacy in the auto industry—have leapfrogged to leadership positions. In 2023 and 2024, Shenzhen produced 1.73 million and 2.93 million NEVs respectively, becoming the country’s top NEV manufacturing hub—and for the first time in 2024, earning the title of China’s top auto-producing city overall.

Other municipalities—Shanghai, Xi’an, Hefei, Chongqing, Guangzhou, and Beijing—have engaged in fierce competition to attract and scale EV firms.

Many local governments now employ performance-linked agreements with automakers. Unlike previous preferential policies, today’s local governments are partnering with high-performing firms (‘champions of the game’) on such incentive-based deals to increase chances of success. The most well-known example: Shanghai’s deal with Tesla.

In exchange for discounted land, low-interest loans, and temporary tax exemptions, Tesla committed to localizing production, investing heavily, and meeting future tax and employment benchmarks. In economic terms, this was a bet: short-term tax relief in exchange for long-term fiscal return. And Tesla delivered.

Often these arrangements aren’t formalized but rather implied: governments support firms today in exchange for future tax revenue and industrial growth. The “champion firms” in this game—BYD, NIO, Li Auto, XPeng—have mostly kept their promises.

These policies—particularly tax relief and performance-linked agreements—have undeniably fueled production. But they’ve also led to surging capacity across the sector.

The Next Challenge: Boosting Consumer Demand

With factories humming, China must now turn its attention to stimulating consumption. That means shifting tax benefits from corporations to consumers.

The goal: increase household income as a share of GDP and ensure that ordinary citizens have the disposable income needed to drive demand.

Where will the money come from? One answer: rebalance land pricing. In China, residential land is priced far higher than industrial land—an implicit tax on citizens to subsidize firms. Equalizing land values would both reduce distortion and increase consumer spending power.

Tax reform has historically played a pivotal role in China’s growth. Economists know that lower taxes reduce economic friction and encourage expansion. The explosive rise of NEVs is one such example.

The Takeaway

In Latin, quid pro quo means “something for something”—an exchange of mutual value. This captures the essence of China’s EV strategy: local governments and private firms working together in a high-stakes, high-reward partnership.

Yes, subsidies played a role. But it is the tax incentives, market competition, and relentless innovation from private firms that have powered China’s EV dominance.

Meanwhile, the collaboration between local governments and private enterprises has fueled the industry’s rapid ascent—but this path is no longer sustainable, with excessive internal competition being its most obvious drawback.

This overall model, while successful, now faces growing strain: overcapacity, intense competition, and weak household consumption signal that a new phase is needed.

Western observers often misread China’s industrial playbook. But understanding this internal logic is essential—not only to interpret China’s past success but also to anticipate where its economy is heading. Only then can the right ‘remedy’ respond to the true nature of China’s transformation and boost its further growth.

*Originally published in Chinese language on Jiemian.com here

By Li Wei, Professor of Economics, Associate Dean for Asia and Oceania, Director of Case Center and Director of Big Data Economic Research Center at CKGSB