Long kept at arm’s length, will foreign bank card companies finally get a fair crack at the China market which is dominated by UnionPay?

For over two decades foreign payment card companies such as Visa and MasterCard have been vying for a piece of an ever-growing debit and credit card market in China, which is expanding rapidly off the back of a move away from a cash-based economy. Standing in their way has been the state-backed bank card giant UnionPay and regulations that in 2012 were judged by the World Trade Organization (WTO) to be discriminatory against foreign businesses, with many accusing the company of acting as a monopoly. That same 2012 decision rejected that assertion, but its ruling against certain regulations raised hopes that finally the likes of Visa and MasterCard would have the access they crave.

Since then, the companies have largely been frustrated in their attempts to fully enter the country, with UnionPay continuing to dominate the scene—according to Datamonitor, in 2013 78.2% of debit cards issued were UnionPay cards. However, a ruling by the State Council, the country’s chief administrative body, in October stated that China’s payment clearing market was to be opened up to foreign competition, one of the key points of the 2012 WTO decision, again raising expectations about the prospects of foreign card companies in China.

But just as quickly as those hopes were raised, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the country’s central bank, introduced a compulsory new technological standard for certain bank cards, effectively blocking UnionPay’s foreign competitors from China. In doing so, China risks running afoul of its WTO obligations, and as such a further WTO dispute possibly looms on the horizon. But even if the likes of Visa were to gain full access to the Chinese market, it is not clear whether they would stand a chance in the country anyway.

Golden Card

Established in March 2002 under the auspices of the State Council and PBOC, and owned by an array of Chinese state banks and entities, UnionPay was a means of modernizing the country’s financial system while also establishing a ‘national champion’, with its roots stemming back to the Golden Card project in the 1990s. To this day, UnionPay maintains close links with PBOC, with many former central bankers going on to senior positions at the card company, not least Su Ning, UnionPay’s former chairman.

“By creating UnionPay, Chinese authorities would have a powerful tool in which they could influence the market significantly,” says Tristan Hugo-Webb, Associate Director of Mercator Advisory Group’s Global Payments Advisory Service. “Other reasons for creating UnionPay are decreased reliance on the international card networks and greater control over future initiatives like financial inclusion.”

With the newly established organization in place, all RMB-denominated transactions were to be cleared using UnionPay’s network, sowing the seeds for the disputes that were to later follow. Although MasterCard and Visa have had some presence in the Chinese market for a long time now—as early as 1987 the Bank of China had issued Visa and MasterCard-branded cards—they were required to partner with UnionPay as they were unable to process domestic transactions themselves, build their own networks or issue their own cards.

As a result, when Visa or MasterCard bank cards were issued, they were co-branded with UnionPay.

Meanwhile, UnionPay was expanding internationally off its domestic strength and the increasing number of Chinese tourists going abroad, particularly those on luxury shopping trips. All of which was very much in line with the government’s expectations—in January 2010, the-then President Hu Jintao visited the company and encouraged its international expansion (a plaque in the headquarters commemorates the visit).

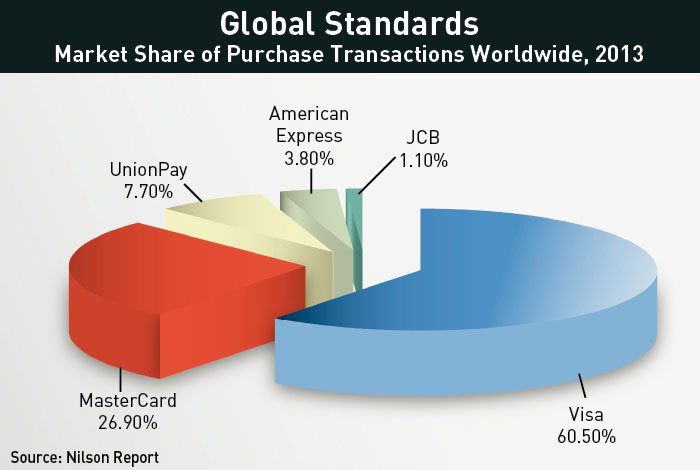

Today, the company claims its cards are accepted by over 13 million merchants and 1.12 million ATMs outside of mainland China. UnionPay’s global circulation of payment cards is expected to grow 51% between 2012 and 2017, according to the Nilson Report. By contrast, Visa and MasterCard are expected to grow 28% and 36%, respectively, during the same period.

Pushback

In the year before Hu’s visit, UnionPay had begun to process international payments from Visa co-branded cards through its own network, rather than Visa’s, thus reneging on the terms of its partnership with the American card company. This precipitated a deterioration in the two companies’ relationship, and the following year Visa was blocked from doing business in China for a year, an event that led to a case being brought against China at the WTO.

Instigated by the US, and joined by Australia, Ecuador, the European Union, Guatemala, Japan, Korea and India, the complaint stated that China discriminated against foreign providers of electronic payment services, which, as per its WTO agreement, it was supposed to have opened to international competition by 2006.

In response to the 2012 WTO ruling, China scrapped five PBOC regulations in 2013, claiming that this was sufficient. But according to Bryan Mercurio, Professor of Law at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, a subsequent agreement between the US and China that extended the time to respond to the decision by 2015, indicates that China knew it was not compliant with the WTO ruling (although the document for this agreement has not been made public).

The October State Council ruling, without mentioning the WTO ruling, finally seemed to be a step towards opening the way for full foreign participation in the electronic payment clearing market, and thus compliance with the ruling, but it did not go into specifics nor give a timeframe. However, the South China Morning Post quoted an anonymous department head of Goldpac Group, China’s largest credit card supplier, as saying this would be done by August 2015, and PBOC has reportedly submitted a draft regulation to the State Council following its decision.

Susquehanna Financial Group, an equity research firm, estimates that if these measures were implemented in time for Visa and MasterCard’s entry into the market in 2016, that year they could see their revenues increase $260 million and $180 million, respectively. But just days after the ruling, in early November PBOC announced that all smart cards—payment cards equipped with chips—must conform to PBOC 3.0 standards. These standards govern the way account data is transmitted at an ATM or checkout, and PBOC 3.0 is only used by UnionPay. The global industry standard, EMV, is incompatible with it due to different encryption methods, and as such PBOC’s decision would require Visa, MasterCard and other foreign payment companies to overhaul their businesses in order to participate in the China market, raising the question of whether China is in violation of its WTO obligations.

Mercurio calls this a “violation”—with caveats—of its WTO agreement, but with regard to the Technical Barriers to Trade agreement, as opposed to its Services agreement, where the case would be less clear. “In picking the home standard that’s not the standard anyone else uses, it appears to me they’re creating an unnecessary obstacle to trade,” he says. There are some opt-outs to this, such as national security, but China has unsuccessfully pursued this approach before with its WAPI wireless standard.

To be successful in that strategy, China would have to demonstrate that the PBOC 3.0 standard was an improvement on EMV. “If the Chinese can demonstrate that the Chinese national standard supports a higher level of security than is possible with international standards, then there is no WTO violation even if that decision fragments the architecture of the international market for payment services,” explains Jane Winn, Professor of Law at the University of Washington.

Mercurio points out that this then becomes a highly technical question, and so he is not in a position to answer whether it is or not, but says, “I think there are some serious doubts as to [whether it’s an improvement].”

Given the US government’s previous willingness to take the dispute to the WTO, Mercurio thinks it is “fairly likely” that will happen again, but this will in part be a political calculation by the government and Visa and MasterCard, who might be concerned about how it will affect their market access.

Winn is less convinced, noting that companies in many industries will be vying for the US government to take a case to the WTO, and Visa and MasterCard will be but two of them, if indeed they are keen for a case to be made. “Every major WTO member state has a long queue of private companies that want the WTO invoked to protect them, and they cannot file complaints on behalf of all of them. Governments have to balance the interests of competing domestic industries against each other and against larger national strategic concerns in deciding whether to file a complaint,” she says.

“As a competitor coming in, you would call it a way of blocking [access],” says Arnie Cho, a consumer payments analyst at Datamonitor Financial. “I think it is a way of blocking it.” But he argues that it is also a way of avoiding a reliance on foreign companies, a policy the Chinese government have pursued in other sectors. “They don’t want it to be dominated by one single foreign company.”

Eyes on the Prize

By the end of 2013, 4.2 billion bank cards had been issued in China, an increase of 19% on the previous year, according to PBOC. That same year, bank card transactions valued RMB 423 trillion ($68 trillion), a 22% year-on-year increase. The average consumption amount per transaction was RMB 2,454 ($395), an increase of 6%.

Research by Nielsen published in 2014, and based on a survey conducted in August and September 2013, indicated that 71% of consumers in top-tier Chinese cities prefer to use cards. Moreover, 44% use two or more payment cards on a regular basis—the highest percentage out of any of the countries surveyed by Nielsen.

But the presence of foreign card companies in the market is minor. According to data from the Nilson Report, of all the cards issued by China’s big four banks in 2013 in the Asia-Pacific region, only 3% were Visa or MasterCard (the banks only operate a handful of branches outside of mainland China). However the vast majority of money is still spent on debit cards, giving an indication of the potential for growth in credit cards, and this could be an area where foreign companies might still be able to make an impact, if they can get the access.

The growing e-commerce market also adds impetus. “There is no doubt that the Chinese e-commerce market is going to be the largest market in the world for the foreseeable future, making entrance into the market that much more crucial for the card networks,” says Hugo-Webb.

But even if foreign companies might feel they have to be in the country, Chinese consumers and business owners might not mind if they’re not. Julie Zhu, a restaurant owner in Shanghai, accepts MasterCard and Visa as well as UnionPay, but her preference for one of the three is clear. “I think UnionPay is more convenient… our biggest concern is it charges us less,” she says.

UnionPay’s relatively lengthy history in China and consumer recognition help give the company its dominance, and “because they have the market at scale in China, they are able to charge a much lower fee, and that’s very crucial to the acceptance,” says Cho.

While foreign card companies might struggle to compete when it comes to fees, that hasn’t stopped them trying to appeal to consumers with deals and gifts that come with their cards. In January, Visa unveiled an array of product offers for their most affluent users in the areas such as hotels, travel, dining, health and education.

But complicating matters is the fact that both UnionPay and the foreign companies now face a threat from third-party payment services, which can cut the card companies out of the process by connecting directly to the banks. Alibaba has made moves in this area with Alipay, and last year Tencent received a private bank license for its WeBank.

UnionPay has already requested that banks move this activity back on to its network, yet at the same time it is reportedly looking to get a slice of the action by working with Apple Pay. Meanwhile, perhaps wary of the threat to UnionPay, in March 2014 PBOC ordered the suspension of online payments using QR codes and virtual credit cards in smartphone payment systems, citing security concerns.

“Many in the industry believe this was a move to protect UnionPay revenue,” says Hugo-Webb. “With Chinese authorities still very influential in the marketplace, there is always the potential for authorities to attempt to intervene if they see UnionPay under threat.”

But Winn points out that PBOC aren’t the only ones to express skepticism about the safety of some of these systems. “The US Federal Reserve has also highlighted the security risks associated with using QR codes to process payments. It is not unreasonable for a national regulator to require payment industry players to prove that the risks of a new technology can be managed before allowing it to be deployed on a large scale,” she says.

Either way, Cho describes the emergence of these technologies as “bad timing” for Visa and MasterCard. If they were to try to run such services themselves, they would be up against issues of localization and their rivals’ better understanding of the market.

“UnionPay and major third-party payment service providers are definitely entrenched in the market and it will be extremely difficult to encourage consumers to switch without major incentives, and that is not sustainable over the long run,” says Hugo-Webb.

Given that, PBOC 3.0 will have achieved one of its probable aims. “It could just be a measure of buying a bit of time,” says Mercurio. “There’s too many technical and economic hurdles for Visa, MasterCard and others to capitulate and adopt the Chinese standard—I don’t see it happening.” In the meantime, the companies will have to attempt to find workarounds. In 2013, PBOC blocked MasterCard from processing RMB transactions through a partnership with the company EPayLinks that made use of “virtual” cards.

But given the prospects, Visa, MasterCard and the rest can’t ignore the Chinese bank card market. Prolonged government protection of UnionPay will have put them at a huge disadvantage, but the foreign card companies will still want to fully participate in the market once they can. “China dares to do this is because of its market size,” says Cho.