Tencent is creating a whole universe in its WeChat app, and could become Asia’s preeminent internet company in doing so.

Alex Zou can’t imagine life without WeChat. The Hong Kong-based private banker and Beijing native uses Tencent’s ubiquitous mobile app to pay his bills, hail a taxi, order food and shop. “I spend about 40% of the time I use my smartphone on WeChat,” he says. “It’s useful to chat with my friends, but it’s the convenience of the other functions that makes it so important to me.”

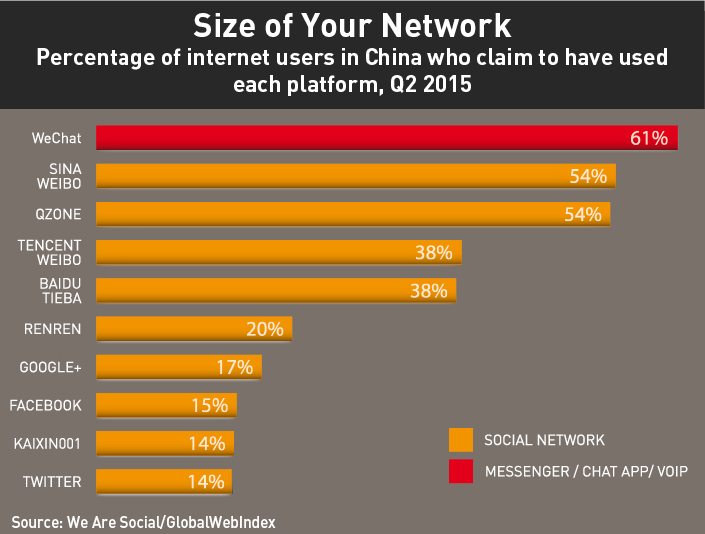

In just over four years, WeChat has evolved from a simple free messaging app into China’s paramount mobile portal. With 650 million monthly active users, it has a commanding position in the world’s biggest smartphone market.

Tencent has used WeChat to create a mobile ecosystem for China, which has more smartphone than PC users. By steadily integrating value-added services into the app, Tencent has made it increasingly useful to both consumers and businesses.

That innovative strategy means WeChat has more opportunities than other messaging apps to make money. In contrast to Facebook, which earns most of its revenue from advertising, WeChat monetizes by integrating online payment functions that encourage shopping through the app and selling games. In the second quarter, Tencent recorded RMB 4.5 billion ($701.4 million) in revenue from games purchased through WeChat and its older instant messaging app QQ, up 11% year-on-year.

Analysts are sanguine about WeChat’s potential. Nomura Securities estimates WeChat’s average revenue per user (ARPU) is at least $7—seven times the ARPU of WhatsApp, the top messaging platform globally.

At the same time, WeChat’s disruptive capacity is formidable. It has hobbled text messaging in China—once a big revenue source for China’s telecom carriers—and curbed the clout of Sina’s Web-based micro-blogging service Weibo.

With a dominant position in China and Tencent’s vast resources at its disposal, WeChat could become one of the most powerful apps in the world.

Made for Mobile

WeChat grew out of Tencent’s efforts five years ago to take the lead in China’s then ascendant mobile internet market. “Executives realized they could no longer rely on PC games and the QQ messenger service to drive growth,” says Jenny Chen, Marketing Manager of WalktheChat, a Beijing-based consultancy that advises companies on how to use WeChat. “They needed a mobile platform.”

In late 2010, Tencent assembled a team of 10 developers in its Guangzhou research and development center to begin work on a smartphone messaging app. “It was an entirely different team than the one responsible for QQ—a team with expertise in mobile,” Chen says. Kik Messenger provided inspiration for the team, whose leader Allen Zhang was concerned the Canadian messaging app could one day threaten Tencent’s QQ.

In early 2011, Tencent launched WeChat. Within a year, the app had attracted 50 million users, and by the first quarter of 2014 it boasted 396 million users globally, according to data compiled by Tencent.

How did WeChat grow so fast from the onset? For one thing, it had an early mover’s advantage as the first mobile instant messaging service launched in China, notes Helen Liu, an analyst at the Taipei-based Market Intelligence & Consulting Institute (MIC). Secondly, its easy-to-use and flexible interface design allowed it to integrate smoothly with smartphone contact lists and the email addresses of QQ’s 800 million users, she says.

Some observers have suggested China blocking access to Facebook from mid-2009 helped facilitate WeChat’s rise. “We think the absence of services like Facebook may have contributed in a small way to WeChat’s success, but was not a decisive factor,” says Liu. As a PC-based social-networking platform, Facebook would vie for users with Chinese counterparts like QQ, RenRen and Kaixin, she adds.

Rather, “WeChat arrived in the right place at the time—just as affordable smartphones became widely available in China,” says Jamie Lin, co-founder of the Taipei-based AppWorks accelerator—Asia’s largest by start-up alumni—and an expert on the mobile internet.

Critically, Tencent made voice input a prominent feature of WeChat, betting Chinese consumers—many who had never learned to type on a PC—would prefer speaking to cumbersome Chinese character input, Lin observes.

“‘Push to talk’ let migrant workers in China’s biggest cities instantly speak to their parents living in the remote countryside,” Lin says. “All that was required was a smartphone and internet connection.”

That was an early example of the innovative thinking behind the WeChat app, “the first time voice input was integrated into a social media platform on the mobile internet,” he says.

To be sure, monetization has been important to WeChat’s meteoric ascent. However, “WeChat was not thinking about monetization until 2013,” when it began selling games and launched its payment and official account platforms, Liu says.

Indeed, when WeChat launched, China’s other internet giants downplayed its earning potential, Lin notes. “Alibaba and Baidu didn’t take it seriously,” he says. “They said, ‘you will never make money on it; it’s just for text messaging.’”

There’s An App For That

How wrong they were! WeChat hasn’t just made money; it’s become the go-to mobile platform for China’s 667 million internet users.

Official, or public, accounts are integral to the success of the WeChat ecosystem. There are more than 10 million of these accounts, which WeChat approves after a brief application process. Since the cost of opening an official account is low, they are a valuable platform for small businesses. And since WeChat users can typically complete payment without opening their mobile browser, it is easy to make purchases within the app.

The WeChat public account Kidsbookmama reached monthly revenue of RMB 500,000 ($78,800) by May 2015, just a year after launching, according to WalktheChat. Managed by a publisher and writer of children’s books, the WeChat-only shop is usually open for business just one week a month. That creates an impression of scarcity and incentives quick purchases, while customer service is prompt, says Chen.

WeChat can also be a powerful tool for existing celebrities to boost their star power. Logical Thinking, run by talk show host Luo Zhenyu, is one of the most popular WeChat accounts in China with 3,500,000 followers and 30,000 paid members, according to WalktheChat.

Luo is able to reach a huge number of followers instantly with a daily voice message sent at 6:30 am. His followers are then given the opportunity to buy the exclusive items he sells in his WeChat store. Those include books, seats at private-dining events, artwork and designer furniture, says Chen. For instance, “before selling a book, he lets his followers know the book can only be purchased through his account,” she says.

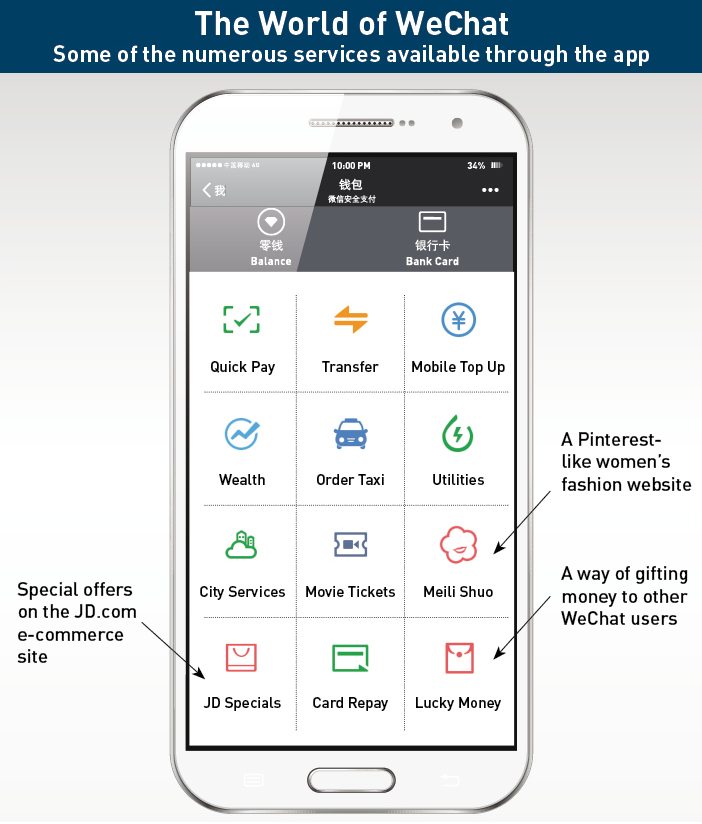

Another pillar of the WeChat ecosystem is payments, used by about 20% of the app’s users. The setup process is quick, requiring users to simply link an ATM or credit card to their accounts. Once that is done, the user can instantly make a purchase on WeChat Wallet services, all official accounts and via any associated promotions.

“It’s incredibly convenient, especially for paying a credit card bill,” says Derek Wang, a sales manager for an advertising agency in Shanghai. “It’s faster than paying via a mobile browser.”

Taxi hailing has become one of the most popular aspects of the WeChat Wallet, buoyed by its integration with China’s popular ride-hailing app Didi Dache—in which Tencent has a large stake. Once Didi Dache—which later merged with Alibaba-backed Kuaidi Dache to create the current company, Didi Kuaidi (the apps remain separate)—integrated with WeChat in January 2014, Didi Dache doubled its registered users from 20 million to 40 million.

Tencent is further developing the financial-services arm of WeChat with the Weilidai loan service, which allows customers to borrow up to RMB 200,000 without guarantee or collateral. The service is operated by WeBank, an internet bank launched in January 2015 by Tencent and Chinese financial firms. With it, Tencent intends to provide micro-loans to consumers and small businesses, to whom Chinese banks typically are hesitant to lend, using data gathered from hundreds of millions of handset users, analysts say.

WeLeaks

With access to all that user data comes the responsibility for Tencent to safeguard it. Yet it is questionable how well the company is prepared to combat cybercrime. In May 2014, cybercriminals used a banking Trojan malware masquerading as the WeChat app to pilfer the financial data of Chinese Android users. When the malicious app was launched, a page appeared requesting users to provide their contact and banking information. That data was then sent back to an email account controlled by the cybercriminals.

More recently, WeChat was infected in the September hacking attack on Apple’s Xcode software used to create iOS apps. The hackers embedded malicious code in those apps by duping developers into using a “tainted, counterfeit version” of Apple’s software for creating iOS and Mac apps, Apple said. After the incident, WeChat said that no user information had been stolen or leaked, and emphasized its preparedness to deal with such attacks.

Meanwhile, following former US National Security Agency (NSA) contractor Edward Snowden’s revelations of Washington’s spying, people are warier than before about protecting their privacy. Some WeChat users outside of China worry their personal information is subject to government surveillance. “I do worry saying something offensive to the government on WeChat could affect my ability to travel to China in the future,” says a Japanese researcher formerly based in Beijing who declined to be named.

According to WeChat’s Terms of Service, “We and our affiliate companies may share your Personal Information within our group of companies and with joint venture partners and third-party service providers, contractors and agents…” including for “security” purposes.

Lin of AppWorks does not think that policy will deter use of the app outside of China. “Besides, the NSA is watching users of WhatsApp,” he says. “You have to be careful about anything you say on any social media platform.”

New Territories

A tougher challenge for WeChat will be recalibrating its China-centric platform for a global audience, analysts say. After all, competition is nil at home, where China’s Great Firewall makes it difficult to consistently access top global messaging apps from Line to Kakao Talk to WhatsApp.

Not having to face foreign messaging apps at home means WeChat is less prepared to deal with them on their home turf. “In the short term, WeChat will have a hard time competing with local champions such as Japan’s Line, South Korea’s Kakao Talk, India’s Hike and the US’s WhatsApp,” Liu says.

Indeed, outside of China, WeChat seems best known among international users with a connection to the Middle Kingdom. Those users find the app handy mostly for its social-networking functions.

Philip Tomlin, a British market research analyst based in London, says he uses WeChat to keep in touch with friends he met while living in China. “A lot of them are not on Facebook and WeChat has the ‘timeline’ function so it’s easy to see what they’ve been up to,” says Tomlin, who worked in Shanghai from 2011 to 2014. “In the UK though, it’s not a mainstream app yet.”

Even in Chinese-speaking Taiwan, WeChat trails market leader Line by a considerable margin. Jay Lin, a Taipei-based software engineer, attributes that to the Taiwanese dislike of voice input and affinity for Japanese brands. “Most Taiwanese are reserved and prefer to type on messaging apps, using stickers [of which Line has many more than WeChat] to express their emotions,” he says. “As a Japanese brand, Line is more trusted here than WeChat.”

Still, WeChat remains determined to expand internationally. In Hong Kong, it has fared better, buoyed by the close links between the former British colony and the Chinese mainland. WeChat is the No. 4 social media platform in Hong Kong with a 23% market share, behind Facebook Messenger, Facebook and WhatsApp, according to a May 2015 report compiled by the Hong Kong-based web design firm Go-Globe.

“I use WhatsApp for my daily communication all over the world, while WeChat is important when we need to communicate with friends and business partners in China,” says Patrick Chan, Director of the Hong Kong-based media services company Kenet Media. “WeChat is a good channel for marketing on the mainland,” he adds.

WeChat has done even better in Malaysia, where it has a 95% smartphone penetration rate, according to Marketing Magazine. Local initiatives are a key part of WeChat’s success in the Southeast Asian country. Those include working with Malaysian designers on localized stickers and using the app as the official platform for voting and interaction with fans on entertainment sites.

In Singapore, WeChat is working with the ride-hailing service Easy Taxi. The launch in the summer of 2014 was a “tremendous success, fueled by the same kind of promotional discounts that helped WeChat become a preferred service for booking taxis in China,” WalktheChat’s Chen says. That strategy helps WeChat to both boost the usage rate of the app and its payment system—which is crucial to making it profitable in the long term, she adds.

The Golden Goose

WeChat’s global ventures remain at a nascent stage, but it looks unstoppable at home. The app’s omnipresence can be explained in part by to the “network effect”, according to Michael Wu, an equity analyst at Morningstar Research. “Combining massive scale, strategic vision, and top-notch execution,” WeChat has been able to “monetize its popularity into a lucrative business,” Wu wrote in an October research note.

With that in mind, consider Tencent’s bid to displace archrival Alibaba’s Alipay as China’s top mobile payments provider. At first glance, that looks unlikely to happen—in the fourth quarter of 2014, Tencent’s share of China’s mobile payment market was just 8%, compared with Alibaba’s 79%, according to research firm Analysys, and Alipay had over 500 million users at the end of last year. But in its third quarter 2015 financial statement, Tencent revealed 200 million users had connected bank cards to QQ Wallet and WeChat Pay.

For now, “Alibaba dominates e-commerce in China,” acknowledges Chen of WalktheChat. “Tencent’s historically been stronger in social media.”

Still, that could change. For one thing, Alibaba has stumbled in mobile before. Its first mobile messaging app Laiwang was a failure, arriving in the fall of 2013 when WeChat had already become dominant. Laiwang failed to accumulate a large user base, while WeChat has only continued to grow.

Chen believes the vibrant ecosystem built around WeChat has been critical to its success. That ecosystem allows Tencent to leverage the resources of all the companies providing “off-the-shelf services” for its platform, enhancing the user experience, she says, adding: “This ecosystem is much more limited for Alibaba and Alipay, and growing at a much slower rate.”

In early 2014, US-based LinkedIn, the world’s largest professional social-networking platform, became WeChat’s first major global partner in China. The partnership made it possible to access LinkedIn’s job hunting and recruitment functions through the WeChat app, while LinkedIn gained direct access to China’s preeminent social network.

The WeChat ecosystem is further expanding as the app moves to tap the emerging Internet of Things (IoT) through its open hardware platform. As of August, WeChat had granted free use of its public platform to over 2,400 manufacturers of intelligent hardware and many millions of individuals who use the app for social networking.

Given WeChat’s ubiquity, exclusion from the platform could crimp the prospects of businesses in China—particularly those that rely on smartphones, analysts say. The US ride-hailing app Uber faces that predicament, after being banned from WeChat earlier this year following the merger of rival apps Didi Dache and Kuaidi Dache.

“WeChat’s ban on Uber is likely to have a profound impact on Uber’s growth in China, especially in the lower-end sector of the ride-hailing market,” says Liu of MIC, adding that Didi Kuaidi already dominates that market with a combined share of more than a 90%. Uber’s best bet, she reckons, is to target the high end of the market—especially foreign business people—where Didi Kuaidi is not as strong.

And despite its travails expanding internationally, WeChat’s global profile is rising: Western messaging apps are now ironically borrowing some of its most innovative functions. “WeChat is influencing Western messaging apps, pushing them toward social commerce and platform integration,” says WalktheChat’s Chen. For instance, Facebook announced in August that it will implement some of the features WeChat pioneered in messaging apps in its own Facebook Messenger, including games, payment and permitting businesses to privately communicate with customers.

Those changes are overdue, Lin of AppWorks says, noting WeChat remains well ahead of its Western counterparts. Facebook’s first stab at e-commerce, the ill-fated Gifts platform, failed to generate substantial revenue for the company and was shut down in July 2014 after less than two years of operation.

“Eventually, it’s going to be possible to leave your wallet at home in China and pay for just about anything with WeChat on your smartphone,” Lin says. “It’s going to happen in China before it happens in the US.”

Tencent, meanwhile, is set to become Asia’s most powerful internet company on the back of rising adoption of the WeChat platform. HSBC reckons WeChat is worth approximately $83.6 billion, or half of Tencent’s market capitalization.

To put it candidly, “without WeChat, Tencent would have become irrelevant by now,” Lin says.