China’s population may be aging past the point of no return

China is the world’s youngest superpower with the world’s largest labor force of nearly 800 million people, but it seems like it has only suddenly realized it is getting old really fast.

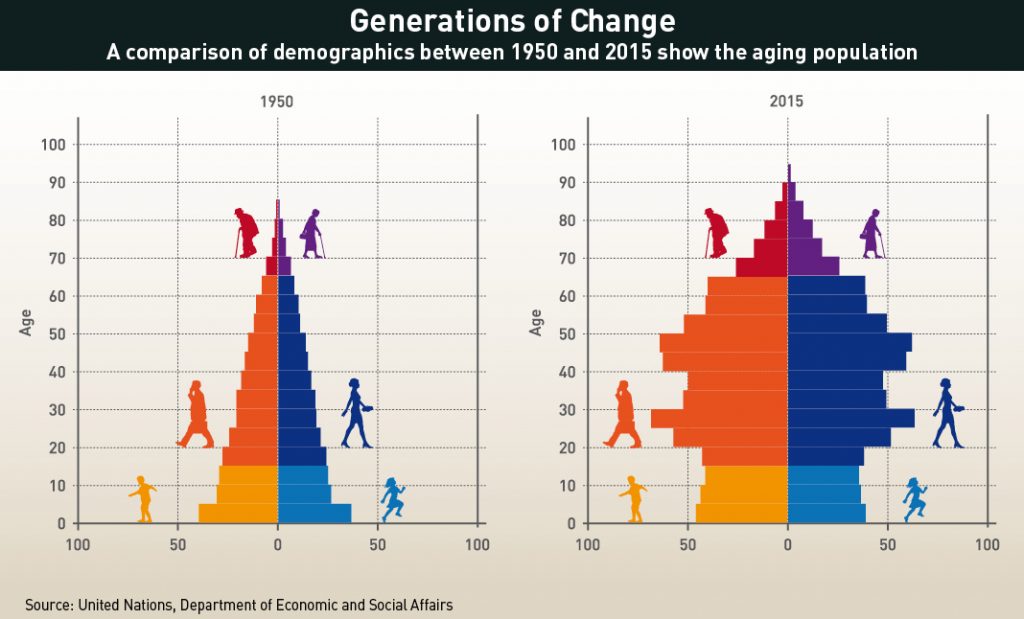

In China today, there are roughly 7.6 workers for every one retiree, but by 2050, according to the United Nation’s demographic forecast, each retiree will be supported by only 2.1 people in the workforce. Fears about how this future math plays out are creeping into society, particularly for younger people who are going to be on the wrong side of that equation.

Urban workers and their employers all contribute monthly sums into state-run pension funds, but many experts say the amounts will not cover payments for the huge extra numbers of people who will become eligible for them. In 2050, China’s over-65 population is predicted to be around 370 million, up from about 138 million in 2014, already the world’s largest pool of elderly at 10% of the population.

“I pay my pension money every month, but I don’t know how much I will get after I retire,” says Li Zijian, a middle-aged employee of an international company. “I hire nannies to take care of my children and do chores, but I don’t think I can enjoy that when I grow old and really need help.”

Li has legitimate reasons to worry. China’s government is already leading a fight against slower economic growth. The country’s official GDP rate fell to a reported 6.7% in the first quarter, from the double-digital rate maintained during recent decades. And in 2012, China’s working population dropped for the first time in decades, as young people aged 15-59 fell by 3.45 million according to official data.The trend is already showing signs of acceleration with a decline of 4.87 million in 2015, the largest decline in China’s modern history.

“China is far from being ready to serve such a big elderly population,” says Jiang Baoquan, a demographer with Xi’an Jiaotong University. “The country needs to do much more to be prepared for an aged society.”

China will be far from alone at the retirement home—Japan, Europe and the US are also grappling with this problem to one degree or another. But unlike its developed counterparts, China is aging while its level of prosperity is still relatively low. China’s population structure is like Japan’s of the 1980s, while its per-capita GDP level has only reached that of Japan in the early 1970s.

By far the biggest issue is China’s low birth rate, which declined sharply in the early 1980s with the introduction of the one-child policy. Given the massive disruption in population growth it caused, and changing social attitudes toward child-rearing, many experts believe it may be too late to climb out of the demographic trap.

The Birth of a Problem

China has been an overpopulated country for many centuries, and has long suffered problems because of it, but the current demographic crisis is a 20th-century creation. During the Mao era, families were encouraged to have many children, helping the population to roughly double to one billion from 1949 to 1979. Starting in the 1970s, the birth rate began to decline naturally, from above 6 in early 1960s to 4.85 in early 1970s. But fearing a Malthusian catastrophe—a crisis caused by overpopulation and insufficient food production—the government introduced the one-child policy starting in 1978.

“Chinese leaders used very simple math while rolling out the policy,” says Liang Zhongtang, a former expert member of the country’s Family Planning Commission. “[They thought] the economy will grow and the people’s conditions will improve if there are less people, but society has its own rules which aren’t that straightforward.”

Under the strictest birth control policy in world history, China’s population continued to expand in the following decades, thanks to its large demographic base and improving living conditions. China’s average life expectancy has also increased dramatically from 43.4-years of age in the early 1950s to 75.4 now, and medical advances are likely to push that number up further. In other words, people linger on today whereas before they would have passed on.

As a result, China today not only has the biggest population of any country in the world, but is also aging faster than any other country in history.

Globally, there is a pattern of acceleration in terms of how long it takes a society to become ‘aged’—that is, when old people aged 65 or above constitute more than 14% of the population. It took France 115 years, the US 60 years, Germany 40 years and Japan 24 years, with a world average of 40 years. For China, however, it may take only 23 years. Another 11 years beyond that and it will turn into an ‘ultra-aged’ society, when the over-65 crowd makes up 28% of the population.

Pension Tension

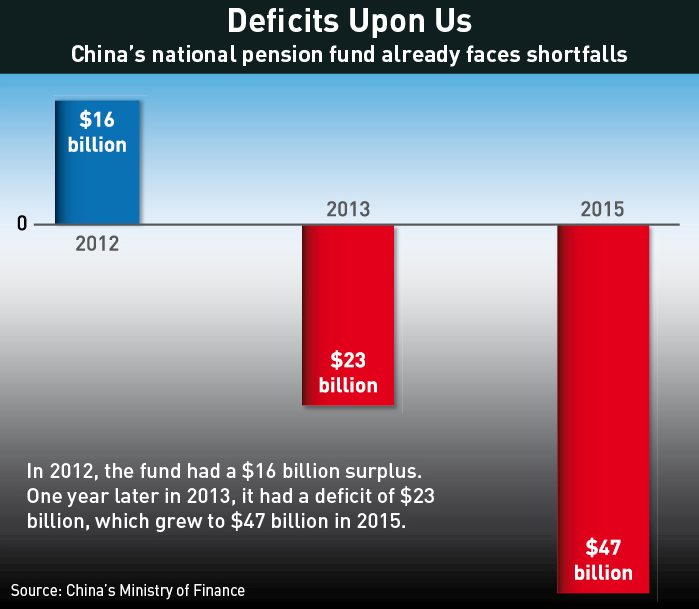

China’s pension system, meanwhile, barely offers a buffer. The system started too late, and it is already using the money contributed by younger people to pay current pensioners. When the baby boomers grow old, the pool will dry up, barring significant changes. Even before that, urban pensioners today receive less than half of what they used to get from the state social security system.

“According to actuarial forecasts, China’s current social security system will have a financial gap of RMB 86 trillion in the future,” says Hu Jiye, a professor with China University of Political Science and Law.

China’s urban employees have to contribute 8% of their wages to individual retirement accounts, with employers contributing another 20%, but most of the money is ‘borrowed’ to pay legacy pensions of pre-1977 state workers.

China set up a national social security fund in 2000, as a supplement to the current pension system and it is now an active investor in the stock market—a move some consider to be risky—while other pension money is generally limited to Chinese government bonds and bank deposits. The fund’s assets totaled $285 billion at the end of 2015, but there is still expected to be a significant shortfall. The country is also allocating more tax revenues to pay pensioners, but that is also becoming a burden on the country’s finances.

“I dare say the problem will be more serious than Japan’s,” says Yi Fuxian, a senior scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Japan’s developed nature put it in a much better position when demographic change hit. It has a social security system that covers everyone, and the universal pension and health care systems were established in 1961, well before the country started aging—from 1970 to 2015, Japan’s elderly population rose from 7.1% to 26.7%, the world’s highest.

But although Japan was able to maintain high pension and social-security benefits, its young people face high tax burdens, and government debt is more than double GDP. The fact that Japan can barely shoulder its burden is worrying.

Fertility Fix?

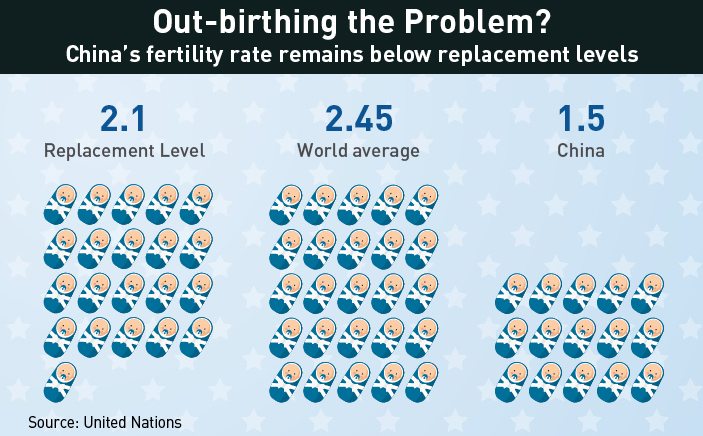

In reaction to the problem, China relaxed its family planning policy in late 2013, allowing a family to have two children if one of the parents is an only child, and the policy was further loosened in 2015, allowing every family to do so. So far the results have been lukewarm—preventing births seemed to be a whole lot easier than encouraging them.

“It was expected that the end of one-child policy may cause two million families to try for a second child,” says Jiang Baoquan. “But in 2014 only 65,000 second babies were actually born. The 2013 policy relaxation did little to boost the birth rate.”

The policy change may be too little too late. China’s fertility rate may have inched up a bit to around 1.5 after the 2015 policy change, but it’s not only well below the replacement level of 2.1, but also lower than the developed-world average of 1.7. Moreover, other low-birthrate countries have had little success in boosting fertility via policy fixes.

In Japan’s case, Junko Yasuda with Nomura Research said policies were launched to help women balance children and work. But Japanese people take having children as a private decision, and seem not much affected by the government.

“The second baby-boom generation that was born 1971-1975 [have] reached the age of 45, so they cannot have many more children,” Junko says. “It means the third baby rush never came.”

In China, the one-child policy fundamentally changed people’s idea of raising kids, making a multi-child family something that most Chinese families no longer aspire to. Raising kids is financially and psychologically burdensome on ordinary people. Simply scrapping the ban can’t offer them incentives to give birth to more kids.

“I can’t afford to have a second child. It will cost me my business,” says Maggie Zhao, who owns an export company in Shanghai. “I will lose my clients if I have to be away for another half year. We run a small business; you need to attend to every detail.”

Maggie’s mother is the one taking care of her daughter, but grandma’s health condition doesn’t allow her to raise another infant. Chinese public kindergartens only accept children after they turn three, and grandparents are usually the caregivers after the mothers return to workplaces. Many working mothers have to choose between babies and work as there is no daycare system in China to take in babies that are only a few months old. There are also no favorable policies for families that only have one adult at work.

Yi said Japan and Korea’s failed efforts to bring up fertility rates offered China more lessons instead of experiences. Encouraging more children would mean restructuring most of the country. China’s high property prices, traffic jams, and lack of childcare options are all standing in the way of increased births.

No One Way Out

With the only real fix of a higher birthrate seemingly moot, China will have to resort to a combination of adjustments to ameliorate the aches and pains of becoming an elderly society.

The shrinking working population can be partly addressed by higher work participation among old people, and this is already being pursued. China’s authorities wrote in the 13th Five-Year Plan that they want to gradually raise the retirement age between 2016 and 2020—in China, most retirees still have the potential to work longer since they leave their jobs before the age of 60. It may also be possible to accommodate more old people in the workplace by providing flexible arrangements.

“People will have to retire later as they are expected to live longer,” says Hu. “The basic rules to keep a pension system balanced is to get back what you paid.” By encouraging people to stay as contributors to the system, the pool will be more balanced with more money flowing in.

China’s traditional family values may also help the society to take care of both the elders and the children, since more Chinese people are inclined to live in big families than in Western countries. But the co-residence rate has dropped sharply as more people moved into cities and grew financially independent. Still, China’s 2010 census indicated that 50% of old people live with their adult children. The government could encourage this trend by relaxing the hukou registration system (which differentiates urban and rural people), or urging migrant workers to work in cities closer to their original homes.

“China is so big that migrant workers might be thousands [of] miles away from home,” says Yi. “It’s almost impossible for them to take care of their old parents.”

China could also encourage more people to participate into corporate annuity plans and commercial pension plans, so elders will rely less on the mandatory state pension system. The country enjoys the highest savings rate in the world as individuals don’t have many safe investment choices beyond banking deposits. By moving part of the savings into the pension plans, the country may restore their safety nets.

Habits of saving starting from a young age will help educated individuals to fare better than others. They could also do better if they were allowed to diversify their wealth from expensive property and bank savings.

But these measures are of little help to China’s poor rural people, who of constitute around half of China’s population. China’s rural areas have more old people than cities as they have channeled the young working populations into the cities as migrant workers. A Shanghai University of Finance and Economics 2015 study shows 15.4% of the rural population is already old versus 13.3% at the national level. The research also shows that more than 50% rural elders are still working, many doing hard manual labor in the fields.

All this means rural old people will likely be hardest hit by the demographic changes. China’s pension system has not yet covered everyone in the country, and rural people can hardly maintain their lives with the 70 yuan (about $10) offered every month by the state pension funds. Many of them have limited savings as they don’t own the land they plant and they suffer from lack of health care services.

“There isn’t much to do about the rural people,” says Hu. “China’s social security system can’t provide every retiree as good a life as the North European countries do. Our fiscal system just doesn’t have the ability.”

Immigration has been the choice of many countries to fill the numbers gap, but it is hardly China’s. China so far is still a net sender of migrants. Between 2005 and 2015, China saw an average of 400,000 people emigrate to other countries every year, mostly developed countries. China may also find it difficult to attract young workers from other countries simply because it isn’t the only country growing old—most of the world is. There is some chance of migration from relatively young countries in the Middle East and Africa if China is willing to open its door to them, but it seems doubtful at best.

“Who would want to migrate to China? [Especially] if its economy slows down while the aging problem worsens,” says Yi. “Africa’s economic growth will pick up thanks to its young population, so their young people won’t aspire to move to China.”

One Foot in the Grave

A greatly aged population now seems inevitable and China can only hope to mitigate the impact. Efforts will no doubt be made to maintain economic growth while the working population shrinks, though an aging-related accelerated slowdown is more than likely unavoidable.

On the other hand, it is still 15 to 20 years away before China’s population really starts to shrink, so the government and individuals still have the chance to move before it’s too late.

“The most important thing of all is… to encourage births,” says Yi. “The country will have hope only if our young people can bring more babies.”