The government is preparing to throw billions into urbanization in China, but has it thought through the hardware challenges?

Perhaps the most striking way to take in China’s startling urbanization is to sit in front of a computer and click through to Google’s Earth Engine. A search for Shanghai on the website brings up time-lapsed images of the city from orbit. In 1984, when the series began, Shanghai was a grey smudge in the middle of verdant countryside alongside a brown streak—the Yangtze River.

Press play and that smudge spreads like an ink stain, with downtown Shanghai becoming darker and the etched lines of Pudong International Airport easily visible. By 2012, the grey patchwork has sprawled out in every direction to leave just fragments of greenery. By 2015, Shanghai will reportedly host the second-tallest building in the world, with construction of the steel titan continuing at a feverish pace in the city’s financial district.

Shanghai’s mushrooming growth is part of the largest urbanization story in human history. The process is transforming China, and in some ways, has only just begun. By 2030, China’s cities will be home to roughly one billion people—three times the current population of the US.

When China began its reform and opening processes in the late 1970s, the country was an overwhelmingly rural one. Back then, with more than 80% living in the countryside, it was the backwaters that supplied most of China’s leaders, who sprung from peasant backgrounds.

Since then China has been transformed. From the 1970s up until the end of 2011, when half of China’s population lived in cities, around 500 million people have added to China’s urban population in the last three years—and the process continues to happen at a terrific rate.

Beijing regards urbanization as the next step in sustaining China’s economic miracle. The push from farm to city will serve as the biggest lever for the country’s economic growth, helping to modernize and transform the country from an investment-driven economy to one that is consumer-driven, according to top government leaders and independent economists.

China’s urbanization drive to date has wrought severe social and environmental problems though, and a new approach is needed. Industries that are key to the process, such as construction, have thus far tooled themselves to deliver quantity over quality, raising the question: Can China actually build the ‘new China’?

The Master Plan

Answering this fundamental question in the affirmative, Beijing mapped out the next phase of that shift from countryside to city in March of this year. China’s long-awaited urbanization plan running from this year through to 2020 is not lacking in ambition or superlatives. The eye-catching headline is that the government aims to raise the rate of urbanization in the world’s most populated country by roughly a percentage point every year, from 52.5% at present to approximately 60% inside seven years.

The bolder portion of the plan will confer former rural residents who are currently living in cities the same benefits and rights that urban dwellers enjoy. By granting urban residency permits, which are China’s internal passports and better known as hukou. This move could transform the lives of up to 160 million migrants, as it will enable them to access basic services and social welfare. In doing so, authorities anticipate the hukou urbanization rate will surge from just over 35% in 2012 to 45% in 2020—a faster increase than the previous decade. To cater to this huge influx of up to 260 million people, planning officials have envisaged 21 mega regions nationwide to harbor the urban population.

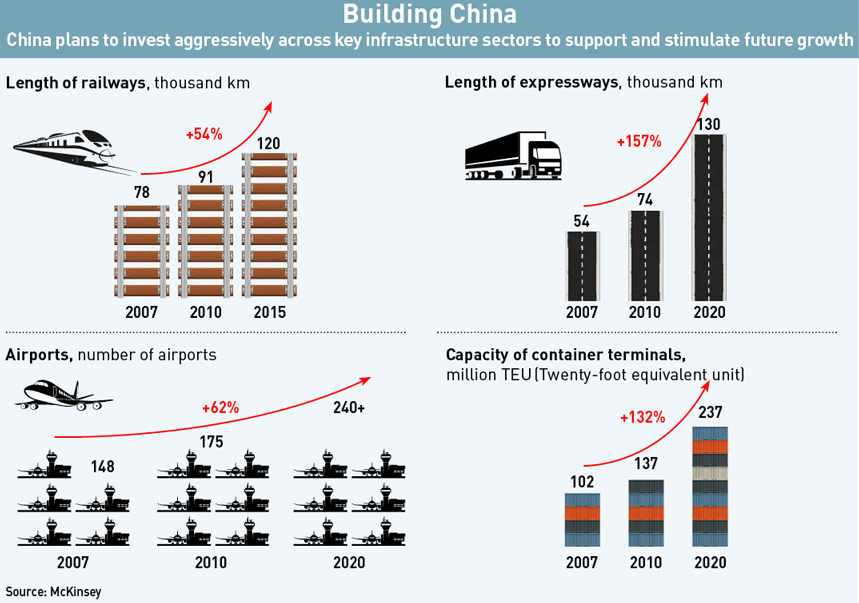

The previous phases of the urban operating model had emphasized the ‘hardware’ of city building—roads, railways, airports, and so on. This approach led local officials to fixate on the size of the city—as this sets the boundaries on urban versus rural population— without thoughtful consideration and planning to ensure effective land usage. Senior officials discussing urbanization in the past typically took it as carte blanche for “another round of infrastructure spending, more steel, more cement, more building, more money, and more investment”, says Qinwei Wang, Chief China Economist for Capital Economics in London.

That fixation came at the expense of ‘soft’ infrastructure—services to assist the urbanizing population, such as schools and hospitals. That is set to change under the plan. Planning authorities this time have vowed to focus on the people populating those urban areas for the next phase, otherwise known as ‘a new type of urbanization’.

“What is new urbanization? How does it differ to China’s last periods of urbanization where they brought 500 million citizens from countryside to cities? I think that had been an era of focus on hardware— transport infrastructure, getting roads, buildings, bridges, and so on—correctly invested into, and now it shifts toward… how to put more livability around China’s urbanization,” says David Frey, Partner at KPMG’s Global China Practice and country head of the consultancy’s Cities Global Center of Excellence.

“China would fail in its urbanization if it simply displaced people from rural to urban,” says Frey. Recognizing such, Beijing intends to build more extensive urban public transport systems—especially in large cities—and a national rail and road network to connect smaller cities and townships. It also aims to increase water and waste treatment ratios—particularly outside of large cities—while expanding broadband internet coverage, increasing the use of cleaner-burning natural gas in place of dirty coal in cities, and more district heating in the north to replace household coal-fired boilers.

A ‘people-centric’ urbanization in China also means theoretically greater spending on social welfare, hopefully to boost consumption of services.

Bottom-up+Top-down

The plan sticks with China’s model of top-down oversight that encouraged bottom-up migration. Migrants moved of their own accord, seeking a better life in cities that were in desperate need of workers as they modernized, similar to how urbanization proceeded elsewhere. There had been a huge impediment to the flow of people from the countryside into cities due to the restrictive hukou system, and until Deng Xiaoping came onto the scene, there were tight restrictions on labor mobility.

At the same time, the role of the state runs deep in urbanization, in contrast with how the process has been largely organic elsewhere. The country’s rapid phase of urbanization, especially in the last 20 years, has been driven by strong government initiative at the central and local levels. “In other places, urbanization just happens,” says Frey. “It’s an economic phenomenon that is a result, not a plan.” City governments welcomed the influx of workers, as they had decided the maintenance of economic growth in their administrations hinged on rapid urbanization—in other words, a building binge on infrastructure.

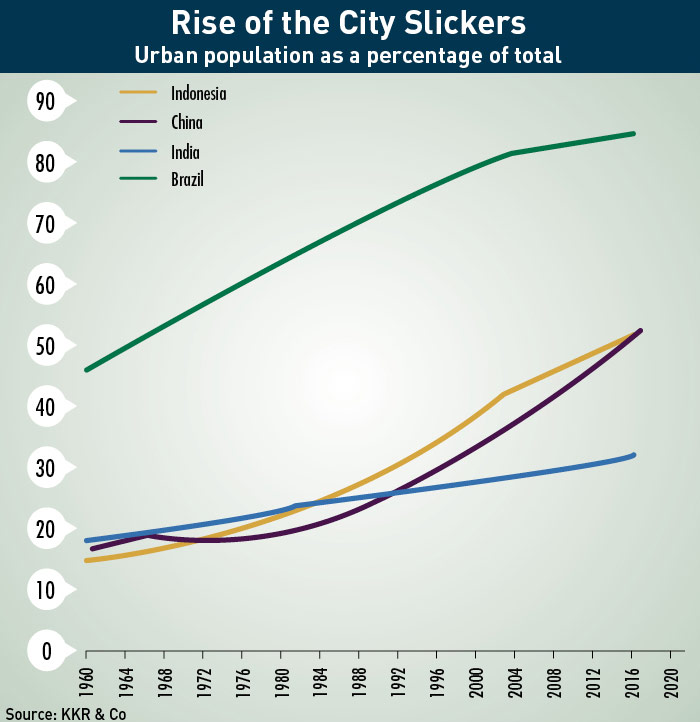

China’s command over the urbanization process stands in stark comparison with the efforts of the world’s second-largest emerging economy. As recently as 1987, India was more urban than China—as a quarter of the population lived in cities, compared with China’s 24% according to data from the World Bank. But China’s pace of urbanization overtook India’s toward the end of the 1990s and raced ahead. More than half of Chinese citizens were urbanized in

2012, compared with less than a third in India. Experts with McKinsey have attributed the overtaking to Beijing’s carefully shaped approach to urban transformation, while New Delhi has been less hands-on.

“If you were to check with urban planners in any economy today, they would tell you that, in fact, the best urbanization—the most optimized urbanization—actually does occur with more planning,” says Frey. Planning that involves much weighing of what to mimic and what not to mimic in other nations’ urbanization models. “In China, when it’s foreign expertise they need the most, they’re not afraid to rush up and get in,” says Kent Zaitlik, Business Development Director of sustainable sourcing and solutions company BEE in Shanghai. “That’s at the helm of what makes China so great, that they’re able to incorporate various learnings from around the world, and then incorporate those insights and techniques into whatever strategy they want to achieve.”

The top-down approach has arguably been vindicated in the relative absence of illegal slums and informal settlements in urban China, unlike other countries that have recently undergone some form of urbanization, such as India, Brazil and Mexico.

“China does not want the type of urbanization like in Latin America, where people moved to urban areas with no jobs and became unemployed and a burden to society,” says Wang from Capital Economics.

Although China’s urbanization has been impressive, it has impressed because of the unprecedented geographical scale on which it is occurring. Not everything has gone according to plan and evidence of China’s unbalanced urbanization has manifested in other ways. “The flaws in the previous model, in which urban construction mostly relied on land sales and fiscal revenue, have emerged in recent years, and the model is unsustainable,” warned Finance Vice Minister Wang Bao’an on the unveiling of the new plan in mid-March.

Spatial urbanization has happened at a much faster pace than the rate of urban population growth—which since the late 1970s has been slower than other countries—encouraged by local governments that seized rural land and sold it to developers to build residential properties, office buildings and industrial parks. Consequently increase in urban land under construction expanded quicker than urban growth, at around 90% versus 52% from 1990-2000, and 83% over 45% in the next decade, according to data from the Ministry of Housing and Rural Development (MOHURD). Between 2000 and 2010, the ratio of urbanization of land to urbanization of population was 1.85, far above the international standard of 1.12 and leading to urban sprawl and the phenomenon of ghost towns.

Building a New China

China’s new style of urbanization envisages half of the new buildings put up by the year 2020 to be ‘green’, compared with just 2% in 2012. It also takes aim at the hot-button issue of chronic smog hanging over Chinese cities, calling for more than 60% of cities to have air quality that meets national standards (particulate matter 2.5 rating between 35 and 75 depending on the location) by 2020, whereas environmental official announced in March that only three of 74 surveyed cities that met with national standards.

The sweeping scale of that mandate evokes skepticism regarding China’s technical capacity to actually carry it out.

“My main concern is with their engineering capacity, with being able to implement some of the things they want to implement,” says Zaitlik from BEE. “I don’t think they really have a firm grasp of some of the engineering feats that need to be taken into account to incorporate some of the green technologies they want to use.”

For instance, Zaitlik pointed to heating, ventilation and air-conditioning (HVAC) design as a particular challenge. “Design of a HVAC system is what’s most important” to green building development, says Zaitlik, as it determines energy efficiency, indoor air quality and comfort. The multinational firms that BEE works with typically have the skill set to design sophisticated HVAC systems, but for Chinese firms, “it’s a different story because their engineering team probably does not have the capability to incorporate some of those technologies fromabroad,” he says. “That is a different kind of thinking that China will almost need a crash course in. That’s what’s difficult.”

Frey from KPMG concurs. “That’s not something you just flip a switch on,” he says. What Frey expects to happen is progressive and talented individuals seizing the initiative in certain cities, with their efforts eventually gaining traction and then replicated across the country over time.

He also points out that developed economies, in their own transformational programs, have also struggled with fostering green development. “No country, no area, no region really has a lock on what that path is, [but] what China has shown is that when it sets its mind to something, it’s pretty good at figuring out how to execute.”

But the industry is plagued with short-termism and is beholden to maximizing profits and lowering building costs—with little consideration for the building’s lifecycle, the environment or the health of the occupants. “They’ve been building like this for years and it’s all about having results, about who brings up the building [the quickest] wins,” says Zaitlik.

He adds that one of the key reasons why the entire lifecycle of a building is not given proper attention in China is because developers run the show.

“Developers don’t really care about the whole life of the building. They just want to get in and get out, as soon as possible. There’re no rules or regulations, or incentives for them really to actually try to go forth and make sure that this building is energy efficient.”

Part of the solution may lie in China’s green building certification, the Green Building Design Label, also known as Three Star. Pushed out by the Ministry of Construction in 2006, it is similar but newer than its Western counterpart Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) and consists of a set of evaluation standards for rating green building sustainability. MOHURD doles out financial subsidies under the scheme on a-per square meter basis, with up to RMB 250 available. Zaitlik says that if adhered to it could grow green constructions quickly, but clearly defining green is crucial.

“If they don’t really… solidify what the meaning of green is, and also have a rigorous process in place to actually show the efficacy of what they’re developing, then it will be a lot of lost money and not much to gain further down the road.” Frey argues that developers will ultimately have to act out of sheer necessity, noting some developers are already awarded projects based on their ability to differentiate with a set of eco-standards.

Some of China’s largest developers are already well down this path, snapping up eco-conscious expertise and knowhow as they look toward the future, according to Frey. Smaller developers are also getting involved by tapping consultancies and institutions like the China Greentech Initiative—a collaboration of greentech firms, government agencies and non-profit organizations that promote greentech solutions.

The Environmental Brinks

In addition to the negative environmental impact of urbanization, social problems in addition are nothing to sneer at. The majority of urban population additions have contributed little to increased spending and consumption growth. Migrants will typically save their money to compensate for the lack of access to social benefits, rendering them not much better off than when living in the countryside in some cases.

From these complications arise vexing questions: is urbanization really the answer or are there alternative options for elevating the quality of life for rural populations? Views are split.

“Most certainly,” says Rena Singer from the Seattle-based Landesa Rural Development Institute, when asked if an economy can be considered ‘developed’and ‘rural’. “Developed refers to standard of living, not place of living,” she says.

Conversely, Frey says a high rural population would indicate underlying problems with agricultural development. Wang concurs, surmising that if the countryside is working as it should, that will simply free people up to move to cities. “[China’s] productivity is relatively low when you consider many people are still in rural areas,” says Wang from Capital Economics. “There’s still a lot of room for China to improve in the agriculture sector, which means China does not need so many people to stay in rural zones to work in the agriculture industry.”

The new plan looks to address agricultural productivity through a number of measures, such as mechanization and the transfer of land user rights from small farmers to specialized farms, rural cooperatives, and agricultural firms—leading to larger farm plots that are more efficient. Wang says a common scenario in the future might be one farmer on a combined larger plot of farmland making a better living and employing workers—versus 10 farmers each farming less than half an acre of land and living in poverty—with the other nine farmers ‘sufficiently’ compensated.

Intensive farming has already taken shape in pig farming. The Jiahua Pig Breeding Farm in Zhejiang province can produce 100,000 animals every year. “In the future, there will be more of these kinds of big farms. It will be more modern and better managed,” says Wang.

Whether ‘rural’ can be equated with developed or not, China’s government is decidedly uninterested in the question. For China, it’s cities all that way, but as Frey notes: “that can only happen if agriculture productivity is rising.”

Not one drop…

China is already a water-stressed nation, a problem that expanding urbanization will presumably exacerbate.

A study by China’s Ministry of Water Resources found that approximately 55% of China’s 50,000 rivers that existed in the 1990s have disappeared. Furthermore, the State Forestry Administration released figures this year indicating that China had lost 340,000 square kilometers of wetlands, that’s roughly the size of the Netherlands.

Unfortunately China has only just started to address its water problems, implementing progressive pricing on water in larger cities, which won’t derail massive water shortages by a long shot.

The key to avoiding that, Wang says, will be smoothing out the migratory patterns. Urbanization has typically favored the wealthier provinces on the eastern seaboard and southern coast, which has in turn increased resource pressures in those parts.

“In the plan, it looks like the government has realized this problem and they want to develop the smaller second- or third-tier cities in broader areas, not only in the coastal areas but in central or west of China, so that will ease tension a little bit.”

In a break with the past, the future pattern of urbanization will likely be slow and measured. “I think China will make a lot of mistakes [but] I also think it will also get a lot of things right,” says Frey.

From a more grassroots perspective, there is a raft of exciting new ‘smart city’ technologies—the Internet of Things, smart grids and meters, and even driverless cars—that are coming to bear, lending a technological element that has largely been absent from China’s urbanization story. Shanghai’s iconic Bund skyline was deemed a space-age pipe dream when it was first conceived, and is now arguably the symbol of New China. So while many aspects of the new urbanization plan seem overly lofty, China may prove again that it does what it sets out to do, by any means necessary.