The Art of Culture

Scene after scene of multi-lingual family discourse forms the backbone of the hit film Everything Everywhere All at Once, the first movie on Western screens in several decades to offer a fresh look at Chinese culture, albeit an eccentric one. With seven Oscars in the bag, the film’s success demonstrates a clear Western appetite for China-related culture.

Even though the world has always been curious about China, the country’s cultural exports have seldom enjoyed the same degree of success as Everything Everywhere All at Once. The movie, an entirely private endeavor that was somewhat ironically developed in the West, had a certain populist appeal which helped it scorch movie charts wherever in the world it was screened. At some level, the movie was emblematic of the difference in effectiveness of the private industry’s approach to building soft power versus that of the Chinese government—a top-down approach to building soft power through committee-designed cultural exports that rarely finds takers. At odds with the more organic and independent cultural industries across the Western world from which the film emerged, the official China approach has yet to capture the hearts and minds of foreign audiences as well as perhaps it could.

Cultural exports are an integral part of a country’s “soft power,” a term coined by American political scientist Joseph Nye in the 1980s, referring to the ability to influence other countries and individuals through non-coercive means such as culture, values, ideology and diplomacy. China’s approach was most recently outlined in a 2022 document, jointly published by 27 government agencies, which seeks to develop “Foreign Cultural Trade” across radio, film and television programs as well as cultural creative and design services.

At a time of rising geopolitical tensions and decoupling from the West, China would stand to benefit greatly from increasing its soft power, but perceptions of China in much of the rest of the world are trending downwards, which could have a serious impact on the country’s future development.

“Increased soft power is obviously good for a number of things,” says Shuang Meng, Associate Professor at the School of International Trade and Economics at the Central University of Finance and Economics in Beijing. “It helps with international trade and attracting international investment, so it is good for economic and business goals on the one hand. On the other, it can also help the Chinese government to have more of a voice in international institutions and international cooperation.”

Soft or hard?

Soft power is a subtle phenomenon as it often operates on subconscious or emotional levels, influencing the beliefs and values that people hold—think Marvel or K-Pop. Building strong positive impressions, trust and credibility takes time, and the benefits of soft power are often not immediately visible or easy to quantify.

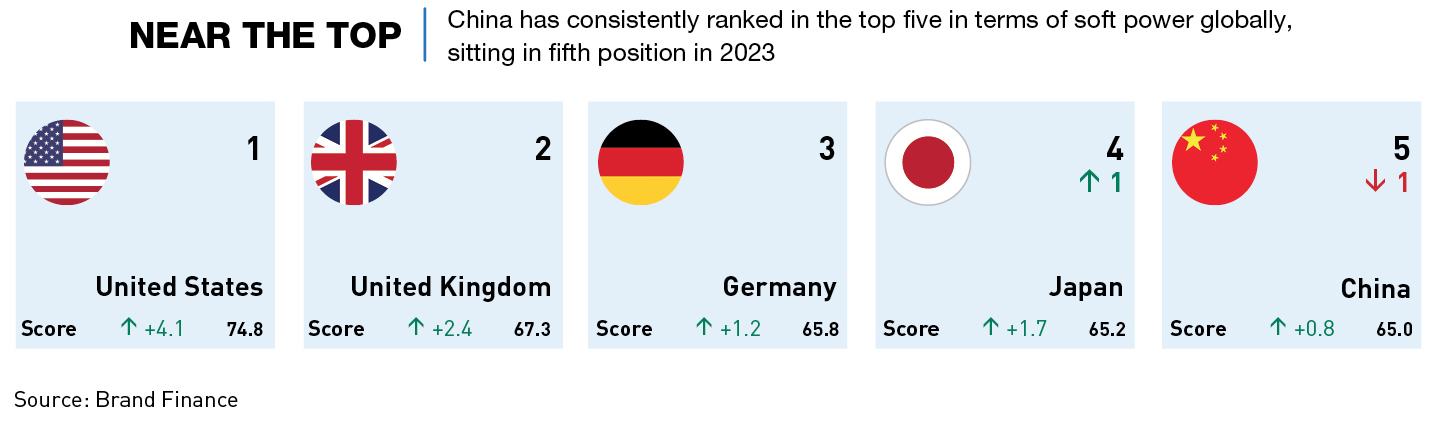

Most research on soft power to date has centered on developed nations and almost equates soft power with liberal values. The Brand Finance Global Soft Power Index, which aims to eschew this historic bias, ranks ‘nation brands’ based on the responses of 100,000 stakeholders across the world on a number of topics, including whether they have favorable views on a country’s People & Values, Culture & Heritage, Business & Trade as well as Governance.

The United States sat atop of the 2023 Index, and China ranked fifth, down one from the country’s highest ever position the previous year. This may surprise many in the Western world, particularly given the current geopolitical environment, but for developing countries, China has been a growing, and largely positive, presence in recent years.

“They have been very successful at generating soft power in Africa in particular,” says Stanley Rosen, Professor of Political Science and International Relations at the University of Southern California. “They have, by-and-large, been successful in areas where the West and in particular the United States is looked at with a sense of suspicion.”

“For example, they have gained a fair amount of control over African media by buying into it, as well as distributing Chinese programming free of charge,” adds Rosen. “CNN and other major networks will charge you, but China has the state-backed channels that can be given away for free, absorbing the costs thanks to the benefits that come with its ownership.”

China is ranked first globally in terms of favorable opinion on Business & Trade, having leapfrogged Germany, Japan and the US to reach the top. It also sits fourth for Familiarity and second for Influence, with these rankings being boosted by scores from the Global South. But the country’s rankings in the areas of Culture & Heritage and People & Values remain low.

Although the positive impression of China in the Global South is important, and perhaps a precursor of a shifting global system, China also needs to start making more positive inroads into the Western consciousness to further its global ambitions.

“Western liberalism and values, despite being opposed in various ways in various countries across the world, are still common in the social and intellectual elites in many developing countries, even some of the authoritarian ones,” says Li Mingjiang, Associate Professor in International Relations at Nanyang Technological University. “This can be a disadvantage for China as it may result in people being skeptical of close relations to China, even in countries where you wouldn’t expect that to be the case.”

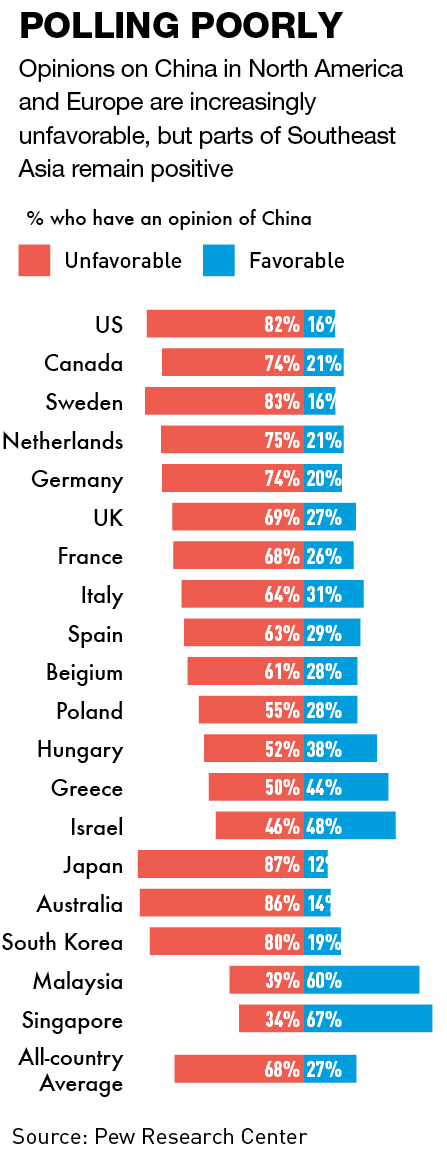

According to the Pew Research Center, the general public’s sentiment towards China in Europe and the US is overwhelmingly negative and has been trending downwards over the past decade—83% of Swedes now have a negative view of China, 82% in the US, 75% in the Netherlands, 74% in Germany and 69% in the UK.

In 2015, many of these numbers were much closer to 50/50, thanks to positivity resulting from China’s rapid economic expansion lowering the cost of living in the Global North. But a recent swathe of high-profile issues have created a perception problem for China, and to rectify that it can no longer simply rely on business and infrastructure diplomacy. Rather, it must advance a more subtle cultural agenda, and it is here that the country appears to be falling short.

“China’s soft power in the world has reached a bottleneck,” says Li. “It is very difficult to make any further breakthroughs or further progress. In fact, there are signs of a regression of China’s soft power.”

Strategic moves

So far, a key component of China’s soft power strategy has been its economic diplomacy. China has been investing heavily in infrastructure projects around the world through efforts such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In doing so, the country has been able to establish itself as a key player in economies around the world and has helped to spur economic growth in many developing countries, in turn building goodwill and by extension soft power.

“China seems more successful in attracting the hearts and minds of part of the developing world when it’s seen as a helpful and capable power and an alternative to the West,” says Daniele Carminati, a Senior Lecturer at Beijing Foreign Studies University. “This is especially true in those countries where the West is still seen as colonialist and patronizing.”

Cultural diplomacy has long been a component of China’s soft power strategy, particularly since former leader Hu Jintao made a speech underscoring the importance of soft power to the 17th Party Congress in 2007. Since then, the Chinese government has undertaken something of a three-part approach, the first of which is the most unique to China.

First, the government decides on the content and target audience of its soft power strategy, setting up committees that create a package that aim to appeal to both Chinese and international audiences.

“In terms of targets, the domestic market is actually the number one priority for Chinese soft power,” says Rosen. “This is followed by overseas Chinese around the world, then the Global South as it was easier to make greater headway there at first than in the more difficult Global North.”

But in most countries with high levels of soft power, decision-making in terms of cultural output is almost entirely decentralized and includes significant grassroots development.

“China is a country that runs top-down, so everything that it produces is assumed to have a stamp of approval from the government,” says Rosen. “This means that there is a perceived lack of independence in creative output, which can harm soft power generation.”

The second step is the promotion of Chinese cultural products and values, drawn from the country’s rich traditions, art and literature.

The final step is to create the channels and packaging through which this information can be successfully disseminated. For this last step, the government has invested heavily—around $10 billion every year—in promoting its culture and heritage. One of the main focuses of the money has been the development of state news outlets such as Xinhua and CGTN, as well as initiatives including the somewhat controversial Confucius Institutes, which are located on many university campuses around the world and largely aim to promote the study of the Chinese language and culture.

China-based companies have also been an important ancillary driver to this three-pronged approach, particularly in terms of cross-border e-commerce and digital platforms.

“There have been, and still are, a lot of people buying Chinese products, building the country’s influence, particularly in countries that are starting to develop an online shopping infrastructure,” says Meng. “Chinese e-commerce platforms are also facilitating this.”

Culture clash

China clearly has an enormous amount of culture and creativity to offer, drawing upon its vast history. And this is now apparent in some areas of its music, movies, gaming, books and across social media. China’s current external cultural impact may be limited compared to its size, but it would be incorrect to say that China has had no influence at all—the British people’s penchant for tea drinking, for example, is a result of imports of Chinese tea that began in the 1600s.

Today, too, there are numerous examples of Chinese culture being deeply ingrained in the lives of people thousands of miles away. One of the most obvious examples is the global ubiquity of Chinese restaurants. The food itself changes to suit different tastes—General Tso’s Chicken, anyone?—but the underlying ingredients and inspiration remain Chinese.

There has also been a solid Chinese presence in visual media. The world has long had a love for martial arts movies, spawned by Bruce Lee and kept alive today by Jackie Chan and animations like Kung Fu Panda, among others. In previous decades, TV shows like the historical drama The Romance of Three Kingdoms have swept through East and Southeast Asia with explosive popularity.

And the country has seen a few recent cultural export successes, such as the popularity of the online game Genshin Impact, published by Chinese firm miHoYo, and the explosion of Hong Kong-born pop superstar Jackson Wang onto the global stage.

“I would say that online gaming is one of the most successful areas for Chinese cultural exports at the moment,” says Anthony Fung, Professor at the School of Journalism and Communication, Chinese University of Hong Kong. “When we play games, we don’t need a strong association with certain countries and they are often somewhat transcultural. There are lots of games out there that you can’t feel a country’s influence on.”

But overall there is still something lacking from China’s soft power output, especially when compared to the successes of its Asian neighbors such as Japan, South Korea and even India. With different results often stemming from different incentives, money or enforcing national will, and approaches, bottom-up or top-down.

“China’s cultural industries may not have the same levels of intellectual property value when you compare them to Japan or South Korea,” says Meng.

Japan’s cultural exports are easily recognized and almost ubiquitous in the Western world today. As well as its food, Japan has also carved out a corner of the entertainment market through the use of anime, manga and video games that allows others to experience stories either based upon the country’s history or related to its popular culture.

One particularly pervasive example is the continued success of the Pokémon franchise. The first iterations of the game were released in the West in 1999, and, having sold over 31 million copies, they remain the best-selling games in the franchise’s history. But the second-highest sellers, with 25.5 million copies sold, are Pokémon Sword and Shield, which were released 20 years after the originals in 2019. The multi-generational nature of Pokémon’s success is a clear victory for Japanese soft power.

South Korea has built an entire industry around its ‘idols’—individual members of the vast number of K-pop groups that have grown in popularity over the last few decades. The most well-known groups, like BTS and BLACKPINK, have enormous almost cult-like followings around the world. And these fans take it upon themselves to learn everything about their ‘idols,’ with many going as far as starting to develop Korean language skills in order to gather more information.

“Although both the Japanese and Korean governments have had some involvement in the promotional process and have assisted private companies and the cultural industries, there was enough room for creativity to flourish and to detach from political and ideological matters,” says Carminati.

There is also India’s film industry, known as Bollywood, which has some cultural reach in the West. Releases such as RRR, an epic action drama which won an Oscar for Best Original Song, and action-thriller Pathaan have seen success worldwide—the latter broke Indian box-office records but made $59 million of its almost $70 million earnings in international markets. It was also the first ever movie to shut down the road outside the Burj Khalifa in Dubai to film there, a feat unmatched by Hollywood.

Fitting in

There appear to be several reasons why Chinese cultural exports, and therefore soft power, have somewhat missed the mark, at least in the West, in recent years. The first, and arguably largest is that the committee-curated nature of the cultural products is at odds with the Western decentralized approach, and discerning Western consumers can easily spot the difference—creativity in the West is often a personal and emotional endeavor.

“In a nutshell, it’s centralized in China and the influence of civil society is limited,” says Carminati. “This means it often feels like a considerable part of the cultural output originating from China disguises some form of ulterior message, while there is more variety and innovation in cultural output from other countries which results in genuine appeal.”

Another barrier China has to cross is that the rest of the world has relatively varied, but largely shared philosophical underpinnings. But China’s history and culture, rooted from the other end of the Euro-Asian landmass, developed in a largely independent way from the outside world. This is not necessarily a bad thing, as it means there are so many new stories to tell, but it does mean a certain level of packaging is required to provide enough context for outside audiences to truly resonate with content.

“Shared history is important but it’s also about shared culture and to a certain extent shared language,” says Rosen. “In countries like France and Italy, the dubbing artists are often more famous than the actors in the films, and dubbing is often preferred to subtitles. But dubbing, say, a Tang Dynasty historical drama in Italian would not work, it would just become a comedy at that point.”

Thirdly, foreign cultures are best absorbed by people if they are tailored to them in some way, but many of China’s cultural exports are, by order of the committees that create them, kept very traditional to maintain a cultural purity. This, along with a lack of appropriate packaging can lead to a lack of interest from foreign audiences.

One example is the 2012 film Lost in Thailand, which was a huge success both domestically and internationally, and was developed with a business model unusual for China of funding by those collaborating on the film, rather than being recruited for an externally funded project which is the norm in China. The motivation and creative control provided by this approach resulted in a perceived level of authenticity, leading to the film breaking box-office records and pulling in over four times the revenue of its prequel.

Culture accumulation

China has a lot more soft power than many people in the West give it credit for, thanks to its business and trade successes and its infrastructure project support for many non-Western countries. But given today’s geopolitical tensions and the reality that much of the world’s decision-making currently takes place in the Global North, more positive Chinese cultural influence may be beneficial for the country and its development.

“There is a great opportunity for China to come up with ideas that can help solve some of the major global challenges,” says Li. “And if China does a good job in this respect, it will gain a lot of positive views and feedback from other parts of the world.”

Culture is a fluid thing, and in order to successfully export it, a level of creative license is required, something that is difficult to achieve through committees. But there is an enormous amount of culture in China waiting to be shared, and the country’s people have proven themselves hugely creative time and time again. “China’s culture has immense potential to attract,” says Carminati. “And I hope it will be unleashed sooner rather than later.”