Can foreign car makers in China continue to dominate the market while appeasing Chinese car companies?

CCTV, Chinaʼs powerful state-run television broadcaster, unleashed a torrent of faulty vehicle claims against foreign automakers in March. First, the network targeted Volkswagen, alleging transmission issues with some of its cars, which led to the recall of more than 380,000 vehicles at an estimated cost of $618 million. The broadcaster then attacked BMW and Daimler, who were accused of selling cars that produced harmful fumes.

The media’s indictment of foreign car makers dovetails with China’s policy to nurture indigenous players. From removing financial incentives for foreign car makers to requiring they launch Chinese car brands, Beijing has tried to curtail the seemingly endless popularity of non-local autos as domestic brands continue to cede ground to their foreign counterparts. Foreign auto manufacturers first set foot in the Chinese car market 30 years ago, fully aware that the state allowed their entry into the market on the condition that they enter into joint ventures (JVs) with domestic firms, who were expected to benefit from their technical expertise. Despite a lack of complete freedom, they’ve flourished ever since, but the latest round of government-sanctioned media criticisms may force foreign companies to change tack.

Slow Start for Chinese Cars

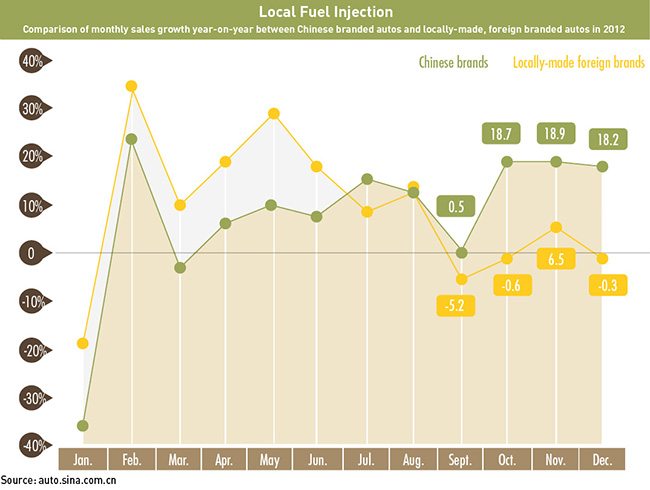

The Chinese car industry has grown rapidly since the nation opened its doors in 1972, shouldering past the US in 2009 to become the word’s largest. Domestic players have profited from this expansion, but their market share is receding compared to foreign car makers: the 30% portion held by Chinese car brands at the end of 2009 fell to 26% in 2012 according to financial research firm Sanford C. Bernstein.

This is not the turn of events China hoped for when it granted foreign auto manufacturers market access in 1984. Beijing knew its car makers were behind the curve on precision manufacturing, so it encouraged JVs with foreign firms to bolster domestic tech-expertise, hopefully leading to a globally recognized national champion.

“The joint venture policy towards the auto businesses in China has always been one of ‘youʼre a guest, youʼre invited and we will tell you the rules by which you must play,ʼ” says William Russo, Senior Advisor at consulting company Booz & Co.

In 1984, Zhao Ziyang, Chinaʼs then premier, said JVs would facilitate the consolidation of the auto market into three large and three small producers, with high levels of local content. Zhaoʼs vision has not come to pass. Different outlets give different estimates—The Wall Street Journal said there were 170 Chinese car makers as of April this year, while the International Business Times cited only 115 companies as of 2012, neither news outlet divulging the source of their information—the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers declined to confirm any specific figure. Either way, even the ballpark is well off from Zhaoʼs prescription.

Not only has consolidation not occurred, but local car makers also remain umbilically dependent on their foreign JVs for profits. Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation (SAIC), Chinaʼs largest car manufacturer, owes 90% of its sales to its foreign JVs, according to a research paper from January this year called “Case Study: SAIC Motor Corporation” published by the US think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). And no Chinese car maker has managed to design and produce a single car that has won global acclaim.

In stark contrast, foreign car makers have thrived. “The Chinese car market is very orientated towards foreign brands. Three out of every four cars sold in China carry a foreign brand,” says Russo.

The China car market, now General Motorʼs (GM) largest, was the US companyʼs savior during the financial crisis, as sales in the nation helped it heave itself out of bankruptcy proceedings in 2009. Since the firm tied itself to SAIC nine years ago, it has amassed 14.7% of Chinaʼs market share, earning a profit of $1.5 billion in 2011 from its joint venture, according to GM China reports. Still confident of its position in China, GM aims to increase sales by 75% in two years to 5 million cars.

China is also Audiʼs most lucrative market. The German manufacturerʼs sales increased by 14.2% in the first quarter of 2013, to almost 103,000 vehicles and it is planning to open a new plant in Foshan, Guangdong province, which will have a manufacturing capacity of 150,000 cars annually when it opens for production at the end of this year according to state-run China Daily.

Still Second Choice

Chinese consumers are buying foreign brands over local ones, because domestic makers are finding it hard to shake off poor repute. “The challenge that Chinese car companies have is convincing their own consumers that Chinese companies in fact can make good cars,” says Russo.

A number of Chinese car brands have failed foreign safety standards, sullying the reputation of Chinese car manufacturers and making it difficult for indigenous brands to market themselves at home and abroad. Brilliance China Automotive, a firm tied to both Bayerische and Toyota, tried to sell its BS6 sedan in Europe in 2007, but earned only one out of five stars for safety from a German car association, which said the driver would have little chance of surviving a side collision.

(Source: Youtube, Youku video here.)

Chinese car companies find it tough to ratchet up the quality, in part because they lag on research and development spending. “Most Chinese companies are thinking five to six years out with their R&D spending and trying to compete with international companies that are already thinking 20 to 25 years out,” says Nat Ahrens, Deputy Director and Fellow of the Hills Program on Governance at CSIS.

This thrifty approach means Chinese car manufacturers have less to spend on nurturing innovative engineering and design. Instead of creating a car from scratch, which would allow them to claim half the patent rights, Chinese JV partners take existing foreign vehicle blueprints, make a few changes and call it a new JV auto: GM and SAICʼs first JV car, Baojun 630, is built on the old Buick Excelle, while Dongfeng and Nissanʼs fi rst Venucia vehicle is fashioned after Tiida. By taking the path of least resistance, Chinese JV companies demonstrate to the consumer their reliance on foreign tech for quality, which does little to raise confidence in their own brands.

Driven to Distraction

The relative success of Western brands against languid domestic ones has sparked indignation and embarrassment among Chinese commentators. In January, Communist Party mouthpiece The Peopleʼs Daily blamed foreign companies for the sluggish performance of domestic players, writing, “Most Chinese car companies involved with JVs have not received the technology they were promised.” In September last year, former machinery and industry minister He Guangyuan said JVs are “like opium” and likened Chinaʼs JV policy to a negative addiction. “So many years have passed and we donʼt even have one brand that can be competitive in the auto word,” He said.

But some feel that Chinaʼs expectations of tech transfer were too high. “I donʼt think any promises were broken, these contracts are laid out very clearly on what was going to be transferred and what wasnʼt… I donʼt think that there was any deception on the part of the foreign partners,” says Ahrens. “You canʼt force technology transfer.”

Market Remodel

As the strength of Western brands has grown, China has pushed back by trimming the incentives and freedoms of foreign automakers. In January last year, China said it would no longer promote investments from foreign car makers through preferential tax treatment and streamlined approval processes, increasing costs for foreign manufacturers.

The month after, Beijing excluded foreign car makers from a newly released list of approved vehicles for government use. While this measure will have little impact on the profits of foreign car makers such as Audi and Mercedes (brands that were included on previous lists), it signaled Beijingʼs determination to freeze out nonlocal competition. In April of the same year, Maxime Picat, the Director General of Peugeot-Citroenʼs Chinese joint venture, said Beijing was threatening to restrict the firmʼs manufacturing expansion plans unless it launched local brands.

The squeeze on foreign auto manufacturers is likely to put a strain on existing JV relationships, making the negotiation process for new deals increasingly delicate. The conflict inherent in a joint venture between two would-be competitors is clear. “A foreign companyʼs interest is not to nurture a local company so that it is as successful or more successful than itself. It will undoubtedly withhold some of its crucial technology,” says Teng Bingsheng, Associate Professor of Strategic Management at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. At the same time, domestic firms are bartering with access to the largest auto market in the world at a time when foreign firms, whose own markets are drying up, can ill afford to be choosy. Under government pressure, the biggest challenge for an existing foreign JV partner will be how to relinquish enough intellectual property to placate Beijing, while at the same time, invest sufficient amounts in R&D to maintain its lead over local and other international players.

But Chinaʼs actions are not likely to wean consumers off foreign brands as the central issue is one of demand not supply. “Government policy cannot change the nature of demand. Chinese consumers will spend their money on the brands they prefer and there is very little that can be done to force Chinese consumers to buy Chinese brands,” says Russo.

This Chinese consumer preference is likely why state media reports went after foreign car makers to begin with, to damage their brand equity in hopes of restoring balance between foreign and domestic brand preference. But it will take more than a few quality-control reports to undo the brand resonance of foreign cars. Chinese brands will have to spend a significant amount of time garnering consumer confidence before they become as popular as well known international car makers.

The Chinese government’s distortion of the market may also have unintended consequences. The launch of new domestic brands by forcing JVs will add another level of competition to an already fragmented market and take business away from Chinese companies who are already struggling to build their market share. By ramping up competition, China in fact weakens the position of wholly domestic brands like Chery and BYD, thus stifling their own plans for a national champion.

“For example, if GM launches a domestic brand, customers that would otherwise be buying a Chery or BYD car will see a car coming from Shanghai General Motors [the GM joint venture with SAIC] and will buy that instead,” says Russo. “So they [the State] are going to eat their own young.”

Just a Fender Bender

Despite Beijingʼs cooling approach to foreign car makers, the countryʼs leaders are unlikely to stifle them completely. “At the end of the day, the government wants to see the domestic car industry succeed, but many of the Chinese companies depend on successful foreign joint ventures to contribute to their profitability and they wonʼt do anything to harm those companies, because that would ultimately harm the whole industry,” says Russo.

In spite of the complications, foreign car makers are finding their tie-ups beneficial in some ways. GM is using SAICʼs low-cost vehicle technology to vault into emerging Asian markets. SAICʼs technology for producing cars priced as low as $4,800 is central to GMʼs plans to plugmiddle-class needs in India and Indonesia. Also it has been reported that BMW and Chinese Brilliance brand Zhi Nuo—which roughly translates as “The Promise”—may start exporting their vehicles to Europe.

The governmentʼs latest measures to suckle a national auto champion are unlikely to seriously dent foreign makersʼ prospects in the short-term. Ultimately, consumer choice determines the winners and losers and the Chinese are increasingly buying foreign brand vehicles. Also, the structure of the market is so dependent on symbiotic JVs that separation in the near term would damage both parties.

The biggest long-term threat to foreign car makers in China is competition from increasingly sophisticated Chinese brands, whose manufacturing skills are developing steadily. Nissan and Honda, two Japanese brands known for their attention to detail, stated publicly that they now outsource heavily to local Chinese suppliers. Quintessentially precise Mercedes-Benz-manufacturer Daimler opened a trial engine production plant in China in May. A decade ago, this would have been unthinkable given the quality of production in China.

Experts draw comparisons between the fledgling Chinese car market and the early Japanese one. In the 1970s, consumers largely thought of Japanese cars as cheap machines. Now, Japanese manufacturers produce premium lines. Hyundai was originally well known for its affordably priced cars, and now makes very innovative, high-quality products. “Great Wall, Geely and Shanghai Auto are capable of making good, quality cars and give an indication that the Chinese car industry will be able to produce a globally competitive car company,” says Russo. “Itʼs a question of time.”