After years of reliance on search ad revenue, it’s time for Baidu to reconsider its business model and diversify

Qian Zhu, a Chinese professional who returned from New York in 2016, was surprised by how China’s largest internet search company Baidu answered one of her queries.

“When I searched ‘Rome, Italy’ on Baidu Map to plan for my trip to Italy, what I got were locations of Chinese wallpaper manufacturers that named themselves ‘Rome’,” Zhu said. Having lived in New York for 16 years, Zhu found one of the challenges readapting to life in China was dealing with the logic of a Chinese search engine.

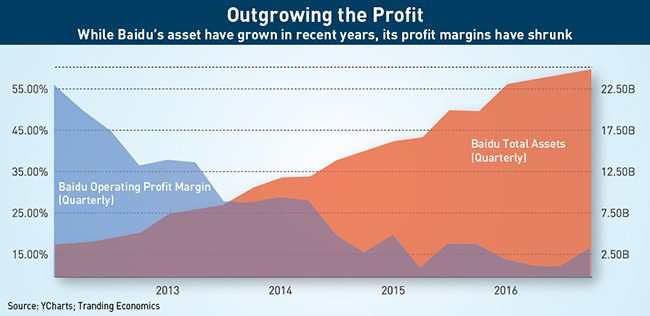

It is one of the milder criticisms Baidu has faced over the past year. In April, the death of a college student named Wei Zexi, who died after mistaking an advertisement on Baidu for an experimental cancer treatment for medically reliable information, generated a nationwide outcry. Both the government and Chinese users accused Baidu of failing to clearly delineate paid advertisements from search results. In July, after an official investigation over the scandal and the release of tightened regulations on search advertisements, Baidu reported its worst quarterly earnings decline since it listed on Nasdaq in 2005.

“The Zexi scandal caused Baidu to cut its revenue expectation by RMB 2 billion per quarter since the second quarter (of 2016), and the impact is expected to last for a year,” says Connie Gu, an analyst with BOCOM International.

The incident has put more pressure on Baidu at a time when web search ad revenues have already been shrinking, raising serious questions about the future of the company, given its reliance on Internet search for its existence.

“Baidu has been overly reliant on search ads to generate revenues, which was a realistic choice during its early development,” says Wei Wuhui, a scholar of media development at Shanghai Jiao Tong University. “But now, such a sales model appears to be insufficient.”

Baidu also faces fierce competition from its two main domestic rivals in the Internet space, Alibaba and Tencent, which together with the search giant make up the so-called “BAT” companies. Baidu is also more constrained than the other two companies that make up the acronym in terms of expanding abroad, due to the omnipresence elsewhere of Google.

Early Success

In fact, Baidu, established in 2000 in Beijing’s Zhongguancun, China’s equivalent of Silicon Valley, is often described as China’s Google, which is true in terms of web search. Robin Li, Baidu’s CEO and co-founder, grew up in a family of factory workers in a town southwest of Beijing. He is now China’s seventh-richest man with a $12.6 billion fortune. In 2015, Baidu had more than 46,000 employees, and reported a profit of $1.8 billion on $10.2 billion revenue.

Baidu operates a broad range of products and services both via computer browsers and mobile, including search, advertising services, statistical tools, maps and knowledge products, a package similar to Google’s core offerings.

Early on, Baidu adopted a strategy to aggressively penetrate the Chinese market, which was greatly different from the US market at the time in terms of maturity and average age of users.

To expand the user base, Baidu initially took a surprisingly non-digital approach by putting large numbers of sales people on the ground. It actively partnered with Internet cafés, popular among young people, and set Baidu as their default search engine. The company also launched products specifically aimed at young users. In 2002 and 2003, Baidu launched MP3 downloading and Tieba, an online message board community, both of which rapidly became popular. By the time of its 2005 IPO, about a quarter of Baidu’s traffic came from its MP3 search.

Although internet users were already using the American company’s services, Google officially opened in China also in 2005, but targeted educated users in big cities who appreciated its professional email services as opposed to Baidu’s fun-based chat rooms.

According to iResearch, Baidu passed Google in number of visitors in 2004 and has been in the lead domestically ever since. Baidu in 2004 acquired hao123.com, a directory for first-time internet users, which was followed by Google’s similar acquisition in 2008 of 265.com. It was not until 2009 that Google launched a music streaming service in China, which proved far too late to be effective.

But Baidu’s victory over Google was also built on its smart interaction with the Chinese government, particularly in the realm of censorship, by deleting certain sensitive search results. Google was effectively blocked from the China market in January 2010 when it declined to continue filtering search results in accordance with official requirements.

Given the realities of China’s regulatory environment, Google has yet to stage a comeback. In 2009, Baidu had 63% of China’s search revenue versus 33% for Google, according to iResearch. Last year, its share of the market by revenue was 80%, with Google still holding 9.2%.

“Baidu’s early success was no surprise, as China’s regulatory environment offered the company an advantageous position over its global counterpart,” says Wei. “In the meantime, Baidu demonstrated a quicker reaction and better understanding of Chinese people’s tastes than Google.”

But Baidu’s triumph has been coupled with criticism. The MP3 service, for instance, has been widely accused of relying upon pirated music, although such problems have by no means been limited to China. There have also been several scandals surrounding search results. In 2008, news reports claimed that Baidu took payments in return for deleting negative news on Sanlu Group, a diary product company that sold milk powder containing melamine, a plastic ingredient, which led the deaths of six children. Baidu denied the reports. And this November, Baidu’s youngest and most promising VP, Li Mingyuan, agreed to quit from Baidu after being accused of engaging in “huge economic dealings” involving acquisitions.

Publicly, much criticism has continued to focus on Baidu’s business ethics, especially in contrast to Google’s, whose corporate motto is famously “Don’t be evil.” After the Wei Zexi scandal, easily Baidu’s most damaging, Robin Li himself openly commented on the difference, contrasting Google’s idealism with Baidu’s pragmatism. He said Baidu perhaps needs to be a bit more idealistic in the future to win people’s hearts.

On the other hand, some Chinese analysts believe Baidu’s pragmatic philosophy is a norm among Chinese privately owned companies, a product of dealing with China’s unpredictable regulatory environment.

“As many other Chinese private-owned enterprises, Baidu understands it has to make quick money and grow bigger in the short term in order to play a power game with the authorities,” says Wei. “The operational risks for small companies can be more unpredictable, but bigger Chinese companies have the power of access to cleverly navigate the regulatory uncertainties.”

However, with changing user habits and the growth of other domestic Internet companies such as Tencent and Alibaba, which were mentioned by Baidu in its 2015 financial report as key competitors, the company is now facing new challenges beyond the search industry.

Baidu’s profit in the second quarter of 2016 was RMB 2.87 billion ($431 million), one fifth of that of Tencent’s profit and one third of Alibaba’s. The gap indicated that Baidu’s membership in the country’s powerful BAT group looks increasingly in jeopardy. And this struggle, too, may be wrapped up with the government and regulations.

“The harsh reaction from Chinese government after the Wei Zexi scandal can be another sign indicating Baidu is losing its position as a powerful Internet company,” says Wei.“With the increasing popularity of Tencent and Alibaba, authorities do not need Baidu as much as it used to.”

Time is running short for Baidu to find a new strategy and new revenue sources, he adds.

Baidu’s Diversification

Despite massive changes in the hi-tech and media space, online ads remain Baidu’s main revenue source, accounting for 97% of the total in 2015. With the increased competition and the downward pressure on online advertising rates, it is crucial for Baidu to diversify its business.

In 2015, Baidu made 23 investments totaling US $1.1 billion in value, with the largest category by number being outside of its core business in Online to Offline (O2O) services (52%), followed by e-commerce (13%), according to research by BNP Paribas.

But Baidu is conservative in terms of investments and partnerships in comparison with Alibaba and Tencent, whose investments last year totaled US $11 billion and US $3.8 billion respectively.

In the Online to Offline (O2O) sector, Tencent-backed Dianping and Alibaba-backed Meituan, both group buying platforms, merged in 2015, giving the newly-formed platform almost 80% market share, and putting great pressure on the Baidu-backed Nuomi. Meituan-Dianping raised $3.3 billion in early 2016, compared to Nuomi’s $169 million ($25.3 million) investment from Baidu. Last year, Tencent-backed Didi Dache and Alibaba-backed Kuaidi Dache also merged to form China’s largest taxi hailing app, adding competition to the Baidu-backed Uber China in the cut-throat online car hailing segment. Uber China finally threw in the towel in August and sold out to Didi.

Generally speaking, analysts believe Baidu’s strategic moves in developing new services has been weaker than its competitors.

“Baidu has lagged its large-cap Chinese internet peers in delivering new commercial innovations,” says Vey-Sern Ling, analyst at BNP Paribas.

According to him, a number of strategic innovations and acquisitions in the past few years have given Tencent a strong position in entertainment, O2O and finance, while Alibaba has also created a value far beyond e-commerce.

“The latter has demonstrated successful organic innovation, such as AliCloud and Ant Financial, and made a large number of strategic investments in logistics, digital entertainment and healthcare,” says Ling. “In comparison, Alibaba has the strongest capacity for further investments and acquisitions among the three. Baidu is the weakest.”

iResearch suggests Baidu is particularly weak in the online finance sector. Baidu Wallet, its online payment tool accounted for only 0.5% market share in China’s online transaction market in 2015. Alibaba’s Alipay dominated with 68.4% of market, followed by Tencent’s Tenpay with 20.6%. In the mobile payment sector, Tencent is rapidly developing a user base for its payment system through the social-networking tool Wechat, which has 700 million active users each month. Ironically, Baidu’s O2O platforms, such as its eye-catching food delivery service Baidu Waimai, link with Tencent’s WeChat platform for transactions, although using Baidu Wallet nets a small discount.

But Robin Li expects Baidu’s O2O services to have revenues far exceeding those of search in the future, given the huge market potential in the sector. But not all third-party observers are so bullish. Vey-Sern pointed out that with high competitions in the sector, higher expenses and uncertain returns are expected.

Similarly, Zhou Xiaoqian, an analyst with iResearch said the increasing cost of logistics and human resources might narrow down the profit of O2O operators in the coming years. The similarity of services by different operators is another problem.

“We see in the past [few] years that the tremendous growth of O2O users is largely built on operators offering subsidies to motivate users rather than innovation,” Zhou says. “In the future, improvement of technology must be the key for success.”

But in fact, that is likely the company’s strongest card. Baidu’s investment in developing artificial intelligence (AI) services is believed to be a strategic move aiming for the future rather than quick returns. All the analysts interviewed took a positive view on Baidu’s AI technology, which is expected to be integrated with services including search, O2O and automated vehicles.

“With the slowdown in the growth of the number of Internet users and the increase in labour costs, AI can help to cut down human resources spending to improve efficiency,” says Connie Gu of BOCOM. “In the AI sector, Baidu is a frontrunner and it has advantages in data gathering.”

Baidu’s AI lab was established in 2013, making it the first-mover in developing AI in China, and it is a cutting-edge developer in the world market. In 2014, Baidu hired Andrew Ng, formerly the head of Google Brain and leading AI expert, to lead its AI team. By 2015, Baidu built Baidu Brain, which is one of the largest computing neural networks in the world. Leveraging this resource, Baidu in September announced the establishment of a $200 million venture-capital unit that will focus on early-stage AI and virtual reality (VR) projects.

BNP Paribas indicated that Baidu’s current innovation is expected to support a strong capacity in deep learning, high performance computing, voice and image recognition, natural language processing, big data, and human-computer interaction in the future. “The early investment together with Baidu’s access to Chinese language search data provides it with a strong head start in the commercialization of AI,” BNP Paribas wrote in a report.

Attempts towards that commercialization of AI have already started. In 2015, Baidu launched a Siri-like AI service named Duer, which has been integrated with Baidu’s O2O platforms including Nuomi, allowing users to get AI assistance in everything from healthcare to travel planning. It has also announced intended public use of autonomous vehicles on fixed routes in select cities in China by 2018, and mass production of driverless cars by 2021. Despite some uncertainty in the business model for autonomous vehicles, Vey-Sern Ling believes the market potential is huge.

“Our conservative projection suggests that the successful commercialization of autonomous driving alone could increase Baidu’s revenues by over 30%,” Ling says. However, Baidu’s plans hit a snag in November, when BMW ended its self-driving cars partnership with the company. Baidu is searching for a replacement.

Globally, China and the US are the two leaders on AI, and both countries have spent tremendous amounts on AI development. The US government in 2015 announced a $1.1 billion investment in AI-related research for both innovation and security reason. That same year, Robin Li proposed the development of a national-level artificial intelligence program in which he said private companies would partner with science research institutes and China’s national defense and military organs on AI development. According to Wei Wuhui, Baidu’s strategically development of AI might enhance its position in China to continue bargaining for a favorable regulatory environment.

Going International

But Baidu still has ambitions outside China. In 2015, 94.6% of visits to Baidu’s search engine originated from China. The US, its second-largest market, accounted for a mere 1.6%, according to Statista, a statistics website. But Robin Li has said he expects Baidu to become a household name in 50% of world’s markets by 2020.

Achieving this will not be easy. Globally, Google is overwhelmingly dominant and highly effective. With only 25% more employees than Baidu, Google generated seven times more revenues than the Chinese company in 2015. In the mobile sector in particular, Google’s Android operating system is the predominant OS globally. With an absence of a competitive mobile system, Baidu’s O2O apps are based on Google’s Android platform.

Baidu’s attempts at internationalization have not gone well. Its earliest expansion was in Japan, where it launched its search service in 2007. Japan was chosen because of cultural similarities to China, particular the use of Chinese characters. But Baidu did not prosper in Japan as it had expected. Eight years later, the company announced the closure of its search engine in Japan due to declining user numbers.

To avoid similar failures, Baidu has adopted a different strategy for its latest round of international expansion. According to Baidu’s president Zhang Yaqin, the company will target Southeast Asia, South America and the Arabic-speaking world as preferred regions, which have large populations and are seen as ripe for mobile Internet development.

Baidu’s expansion rate is now faster than its earlier days, which highlights its growing ambitions. In Indonesia, Baidu branded itself as a ‘mobile first’ company and is aggressively promoting MoboMarket, its app-based O2O service. MoboMarket’s monthly active users increased from 2.9 million in 2014 to 4 million in 2015. Baidu Map, similar to Google Maps and Apple Maps, is set to enter into more than 150 countries and regions all over the world by the end of 2016, and aims to have 50% of users from overseas by 2020.

In Brazil, Baidu’s launch ceremony for its Portuguese search engine was attended by China’s president Xi Jinping, a strong sign of government support. But such support, while offering Baidu an advantage domestically, could in some cases be detrimental elsewhere. Baidu is expected to be preparing for political challenges in international markets, especially in countries with geopolitical differences with China. In 2013, Tencent’s WeChat was targeted for a boycott in Vietnam due to a political dispute with China.

But the ultimate challenge may come from Baidu’s innovation capacity and credibility, which had affected its performance in China.

When asked to comment on Baidu’s international services, returnee Qian Zhu, said, “I’m forced to use Baidu in China because Google is blocked. But outside China, I vote for Google for professional search and mapping services.”

Chinese analysts also highlighted that there are lots of areas Baidu needs to improve to compete on a global basis. The future of Baidu will increasingly depend on whether Chinese and overseas consumers accept the innovations it offers. Meanwhile, there are still improvements to be made to the core services.

“Taking map as an example, the accuracy of the service should be enhanced,” Zhang Xu said.

Needless to say, the future of Baidu will be increasingly based on whether Chinese and overseas consumers would be impressed by its new innovations and enhanced credibility.