Priority Targets

China has made great strides in some areas of the SDGs, but others, particularly the protection of natural habitats, still require a large amount of work

In 2015, China’s leader Xi Jinping stood on stage at the UN Sustainable Development Conference in New York and pledged to help end poverty, fight inequality and tackle climate change by 2030. It was China’s first step along the road to meeting the newly announced Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

“The UN conference on sustainable development has adopted the Post-2015 Development Agenda [including the SDGs], which is the hard won result of the joint efforts of all developing countries,” he said. “We need to build on this momentum to implement the Agenda and make even greater progress.”

As part of the pledge, Xi promised the creation of 100 programs in six areas of international development. Summarized as the “Six 100s,” they covered trade facilitation, ecological protection and combating climate change. Since then, China has made several further high-level statements aimed at guiding the country towards meeting the 17 SDGs, but they are not simple goals, and for a country the size of China, they are proving immensely complex to reach.

“China is enormous, and the level of diversity across the country makes SDG governance very difficult,” says Linda Chelan Li, professor and director of the Research Centre for Sustainable Hong Kong at the City University of Hong Kong. “The implementation and monitoring of policies has always been difficult and a major challenge in such a complex system, and the SDGs are no different.”

Good progress has been made in some areas, but significant issues remain for most targets, and the 2030 Agenda may well prove to be a challenge too hard for China to crack.

Locking on target

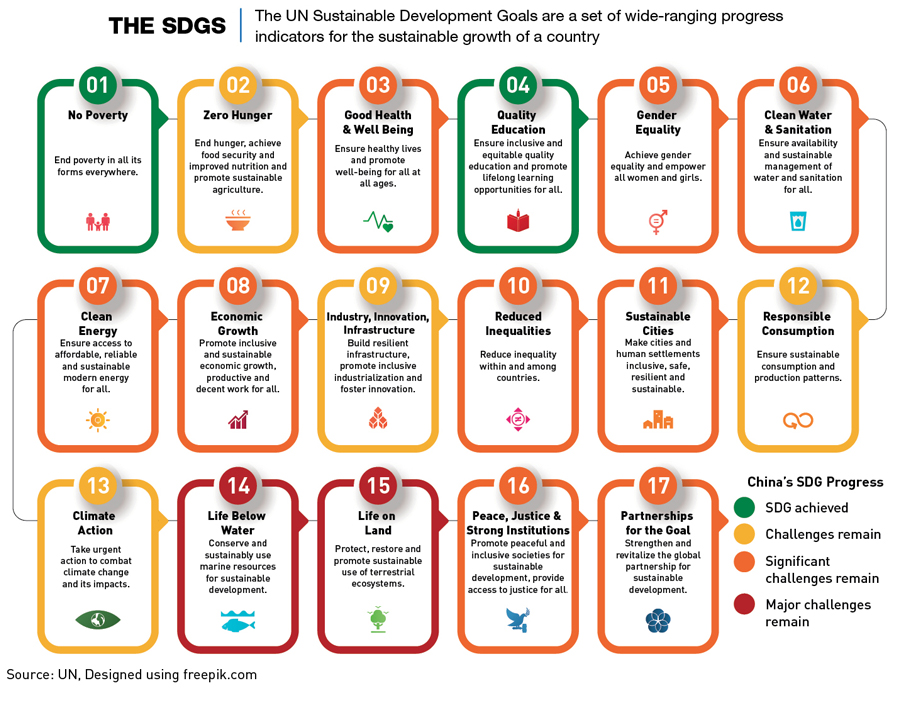

The 17 SDGs, which came into effect on January 1st, 2016, set out the global agenda for achieving a prosperous, inclusive and sustainable society for all by 2030. Covering a wide range of issues, including decent work and healthy economic growth, gender equality and responsible consumption, the goals, divided into 169 specific targets, cover all three dimensions of sustainable development: economic growth, social inclusion and environmental protection.

China’s basic commitment to achieving the SDGs was made public at the time of their introduction, then re-confirmed in 2020, with the release of the UN Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework for China 2021-2025. The document set out a plan for post-2020 development, taking into account the difficulties created by the COVID-19 pandemic, and centered China’s ambitions under three key labels—People and Prosperity, Planet and Partnerships.

“I think it’s natural that China has approached some issues rather than others,” says Tony Wong, founder of Alaya Consulting, which focuses on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues. “If the government already has infrastructure or priorities in some areas, then it makes sense to pursue them over other issues requiring much more money, time and effort. The same argument can be made for businesses approaching the SDGs.”

People and Prosperity relates to achieving innovation-driven, coordinated development, resulting in fairer high-quality economic, social and human growth—goals that are shared with China’s existing common prosperity and business innovation policies. The Planet goal, which targets green development, aligns with the country’s dual carbon goals—peaking emissions by 2030, and becoming carbon neutral by 2060—and an expanding green business sector—solar energy and new energy vehicles, for example. Partnerships refers to greater South-South and humanitarian cooperation to facilitate increased contributions to meet the SDGs. Originally, many of China’s South-South partnerships were driven by the Belt & Road Initiative (BRI), which predates the SDGs but shares a number of commonalities. “It’s not necessarily explicit or in an organized way, but we can easily observe some absorption of the SDGs into the BRI through official rhetoric,” says Li. “In fact, the government has literally described the BRI as the ‘Green Belt and Road Initiative.’”

Approaching the SDGs from an angle that aligns partially or fully with existing national policy targets is not unique to China and other countries are doing much the same. India, for example, has committed to improving health care services by 2027, especially for the most disadvantaged, while South Africa’s SDG-related aims are underpinned by the need to improve inclusivity in economic growth, social transformation and governance.

Scored any goals?

China ranked only 56th out of the 163 countries included in the 2022 Sustainable Development Report, an assessment of countries’ progress towards reaching the SDGs produced by a number of prominent academics including Columbia University’s Jeffrey D. Sachs. The country’s Index Score was 72.4, which reflects the percentage of SDG targets achieved. Finland topped the rankings with a score of 86.51, while South Sudan came in last with a score of just 39.05.

The good news is that China has already met the requirements for two of the 17 SDG goals—Poverty Eradication and Provision of Quality Education. But beyond these, there are only three other areas in which the country’s scores are improving fast enough to reach the targets by the 2030 end date—Clean Water and Sanitation, Responsible Consumption and Production and Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure.

The country is also facing difficulties in utilizing partnerships to reach the goals. Despite being one of China’s three main target areas, rising geopolitical tensions have seen a growing number of problems with effective cross-border partnerships. “Currently partnerships are actually something of a weak point for China, which is unfortunate,” says Li.

Another major challenge is the Life Below Water goal, which is unlikely to be met as a result of massive overfishing, dredging, and lack of protection for underwater biodiversity. A similar lack of protection means that this is also the case for the Life on Land goal. Improvements in these areas have faltered and without a serious shift in policy or business-led countermeasures, China will fail to reach the ascribed targets.

Government involvement

The SDGs have been mentioned in several high-level government statments but the goals were not explicitly included in the country’s two most recent Five-Year Plans, covering 2016-2025. However, there are content overlaps, with both featuring strong emphasis on green development and innovation, but diverging in others, such as gender equality.

“Based on government priorities over the last few years the two goals that stand out are poverty alleviation and climate action,” says Tony Wong. “Beyond these two I think the main thing businesses are responding to from the government is innovation, it permeates everything they do.”

In order to tell how much progress is being made, there is a need for more comprehensive and transparent data on which policy decisions can be based. China is the only one of the 163 in the Sustainable Development Report that doesn’t have a national SDG monitoring system or some level of online report in place.

In 2021, the country made its first concrete steps in the collection and analysis of SDG-related data with the creation of CBAS, a research center hosted by the Chinese Academy of Sciences. CBAS uses high-performance computing, Big Data analysis and AI services to process and distribute data and is intended to be a one-stop-shop for SDG indicator-related monitoring and evaluation. In November 2021, the organization also launched the first-ever satellite developed specifically to help with the implementation of the UN 2030 Agenda.

Despite the clear ambition of the CBAS project, the platform is currently limited to producing data on just six of the 17 SDGs, but usefully, two of the six are targets where the country needs to show the most improvement—Life on Land and Life Below Water.

“Reports from CBAS cite quite a bit of data, and in the areas that they are focusing on there appears to be progress,” says Li. “But the fact that it doesn’t touch on the other SDGs at all is still a major issue.”

Another major issue is data reliability. There is a lack of any independent means to validate the data or conclusions in CBAS reports, a common issue with Chinese data. Another problem arises from the sheer size of the country, with priorities in Shanghai being dramatically different to those in the rural areas of western Yunnan province, for example.

“Even within 30 minutes travel from Beijing or Shanghai, you will have businesses with a whole different set of objectives and desired outcomes,” says Raphael Chan, managing director of NAREE, a consultancy that provides project management services for sustainable development projects. “It’s so hard to standardize anything in China.”

“The country’s diversity makes governance much more difficult,” says Li. “Implementation and monitoring of policies have always been a major challenge in such a complex system. Historically, some level of decentralization has been used in order to stop the center becoming overloaded and help design better national policy and service delivery, but for the SDGs that has yet to be fully evolved.”

Business and the SDGs

One option is for the government to delegate more responsibility for the solutions to SDG-related issues to the vast number of companies, both private and state-owned, that form a crucial part of the country’s economy.

Government statements on SDG attainment contain a large number of references to the importance of public-private partnerships, as well as private enterprise involvement and investment in stimulating progress towards the goals. But turning statements into tangible outcomes is still proving tough. According to a report produced by the UN Development Program (UNDP) in China focusing on private sector awareness of the SDGs, 89% of Chinese enterprises know about the SDGs, but just 10.1% have taken any specific measures to address them.

“For many businesses, especially small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) the barriers are twofold,” says Chan. “The first is that survival is the main priority for many, and the second is that while many business leaders are aware of the SDGs, they lack the expertise to actually implement anything. Some of the bigger companies do have capacity, though.”

Given that SDG-generated economic growth is expected to reach $12 trillion, or 10% of the current global GDP by 2030, with China alone being responsible for around $2.3 trillion of that, it is clear that there are a great number of opportunities for businesses. And many are starting to take advantage of them.

One such organization is the Yibao Program, China’s first financial institution aimed at providing targeted medical protection for low and middle-income people, directly contributing to progress towards the Health and Well-being goal. It provides specifically-tailored products that offer protection against the most common medical issues faced by those in these socio-economic groups, as well as helping prevent a slide back into poverty due to disease.

Companies are also working to encourage growth in areas where the government is currently falling behind, such as international partnerships. Master Kong, China’s largest producer of instant noodles, has embarked on multiple partnerships in Malaysia, Brazil and Indonesia, sharing agricultural management expertise and food safety control technologies.

And these partnerships are clearly SDG-motivated. Master Kong’s 2021 Sustainability Report details six clear actions taken, and four major achievements, including the “assessment of the environmental and social risks of 876 suppliers, the provision of 125.14 customized training hours per employee, and the implementation of the Supplier Relationship Management system which helped train upstream suppliers.”

“Multi-party partnerships are definitely necessary to achieve the goals,” says Chan. “But one problem they often face is a lack of alignment from the individual players in terms of outcome priorities.”

The UNDP is also working with Baidu and Tsinghua University to utilize Baidu’s Big Data capabilities for tracking the progress of SDGs, mapping rural poverty, identifying gaps in electrification, water and sanitation, as well as access to services. The project also looks at mapping similar service trends in urban civilization across the country, aiming to provide policymakers with a clear idea of where improvements are necessary.

And while the Baidu project is an example of improved reporting, the lack of reliable information collection and disclosure remains a major problem for businesses, as with the government. According to the UNDP report, 42% of the businesses who had heard of the SDGs had no clear idea how to evaluate their relationship to the goals, and 38% had never released any SDG-related information. Only 27% of Chinese businesses have produced sustainability reports, while globally that figure is 72%.

“While they do communicate companies’ impacts, the majority of businesses that produce sustainability-related disclosure do so primarily to fulfill regulatory requirements, which depend on the stock exchange they are listed on or the country they operate in,” says Verna Lin, head of the Global Reporting Initiative’s Greater China Region.

Up until recently, many bourses have only required financial statements, but that is no longer enough in many places, and sustainability reporting is becoming a must. “There are business benefits to reporting,” says Lin. “Industry leadership can develop into future value by providing transparency to their global stakeholders, investors and customers, which in turn translate into business opportunities. But developing this understanding in Chinese businesses is a long process. Once they understand, though, they are usually very positive about it.”

The Chinese government could therefore dramatically increase the proactivity of Chinese companies with regard to SDG goals by mandating the tracking and reporting of data.

Educating the masses

As stressed by a recent UNESCO conference on the subject, providing education for sustainable development (ESD) as early as possible in life supports efforts to equip learners with the knowledge, skills and attitudes needed to contribute to a more sustainable world.

Unfortunately, in this regard, a 2019 academic survey indicated that across residents in five cities in China, knowledge of the SDGs was scarce. But a generational difference was clear, and young people showed a much higher knowledge than the public average, particularly on the social and environmental dimensions of sustainability.

One organization that is trying to take on the task of ESD in China is Education in Motion (EiM), which offers school education for a sustainable future and runs a group of 10 educational institutions across China, and a few others in Southeast Asia.

“Our strategic aim is to equip our students with knowledge of ESD concepts and vocabulary, and the ability for them to promote the concepts in the next stages of their life,” says d’Arcy Lunn, Group Head of Sustainability and Global Citizenship at EiM. “It’s important because I think that most Chinese students have come across the ideas before, but there sometimes isn’t really a lot of deeper understanding. And this sort of ESD education and context can provide solutions both for China today, and for the country’s future.”

But EiM, along with some other educational institutes, are moving ESD forward and are eager to see active government involvement in the sector so that further progress can be made. “The Chinese government has set targets of peak emissions, carbon neutrality and other progressive policies and we hope to see even more encouragement to enhance ESD education so these targets and policies can become reality sooner than later,” says Lunn.

Adoption or alignment?

China is definitely making progress in meeting the SDGs, but mostly where that progress aligns with the government’s own pre-determined targets.

“There are many areas in which China is moving towards SDG attainment, but that is not necessarily because they are targeting the SDGs,” says Wong. “Every government in the world has their own agenda, their own targets and their own issues.”

While a fundamental shift in China’s approach to the SDGs is unlikely to be forthcoming, a clearer mandate for data tracking and reporting would allow businesses to increasingly take up the SDG mantle.

“The importance of sustainability reporting is growing and ESG issues are having an increasing financial impact on companies,” says Lin. “It’s a global trend, but especially given the top-down governance approach in China, reporting really needs to be an explicit policy goal.”

Despite the challenges, it is not all doom and gloom. “Globally people have highlighted dealing with climate change as the most urgent of the SDGs that need to be met,” says Li. “Action needs to happen now and the Chinese government is rightly focusing a very large amount of attention in that area.”