Peking Emissions

On a cold winter’s day in late 2021, operators at the Shanghaimiao coal-fired power station in Inner Mongolia marked a milestone with steamed dumplings, fresh fruit and cake. The power plant—currently the biggest in China—had just completed its seven-day-long commissioning, generating enough energy to power one million homes, but it was not necessarily something to celebrate.

Shanghaimiao is a symbol of the collision between China’s longstanding coal addiction and its lofty climate ambitions. In 2021, China reaffirmed its goal of peaking carbon dioxide emissions by the end of this decade and pledged to zero them out by 2060. But since then, China has continued to fire up even more coal power capacity, raising concerns that China is using these last few years to create a high base level for the peak of carbon emissions.

Two years ago, a low-carbon pathway for China’s development seemed to be within grasp. But hopes have since receded, as disruptions ranging from a domestic energy crisis last winter to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, have buffeted the world’s second-largest economy.

“Climate is still very much a priority for policymakers, for enterprises and for provincial officials,” says Alvin Lin, China climate and energy policy director at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “But we are facing a very different environment than envisioned two years ago when those targets were made, and so that is complicating things.”

Hot under the collar

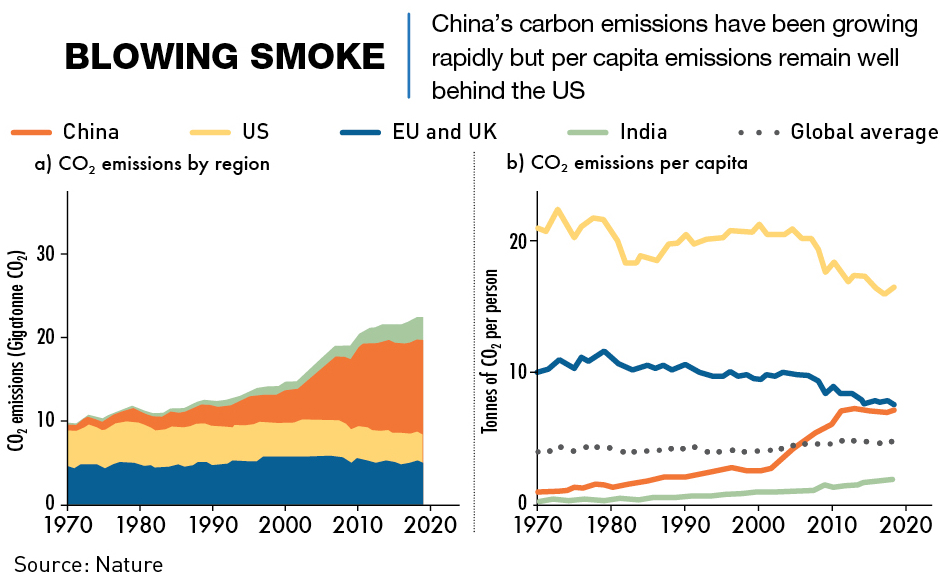

China overtook the US as the world’s largest polluter in 2007, and started to take steps to address its outsized role in global warming soon after China’s current leader Xi Jinping came to power in 2012. The 2030 deadline to peak carbon emissions dates back to 2014 when Xi and US president Barack Obama signed a historic climate accord.

Under international pressure to do more, Beijing tightened up the wording of its commitment in 2021, to say that emissions would peak “before” 2030 or “as soon as possible,” rather than “around” that year. But the wording of the pledge effectively gives China free rein to pump out increasing volumes of planet-heating carbon up to that date.

In 2019, China’s Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions exceeded those of all developed economies combined, and even the global pandemic failed to dent China’s emissions growth. The economic recovery that followed pushed emissions in 2021 up by another 5% to a record 14.1 billion tons of CO2 equivalent.

But Dimitri de Boer, head of China for environmental law charity ClientEarth, says the timing of the commitment doesn’t mean that China is just polluting with abandon until the deadline. The 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP) which covers 2021-2025 sets targets for emissions and energy intensity that should lead to a plateau in the years between now and 2025.

“Much of the permissible emissions growth during the 14th FYP period was taken up when emissions rose steeply from 2020 to 2021,” he says. “The curve must flatten as otherwise the intensity targets for 2025 will be missed.”

King coal

In April, Xi pledged at an international climate summit convened by US President Joe Biden that China would “strictly control coal-fired power generation projects, strictly limit the increase in coal consumption over the 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP) period and phase it down in the 15th FYP period.”

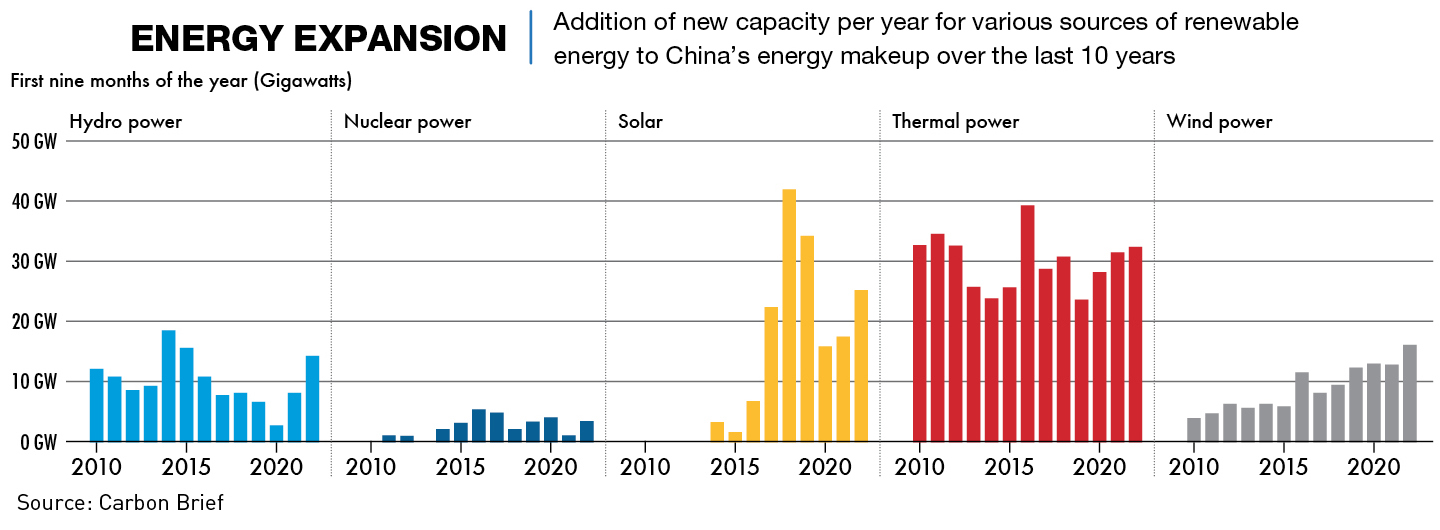

The promise speaks to the titanic role of coal, the worst energy source for GHG emissions, in China’s emissions. The fuel was responsible for generating 56% of China’s primary energy consumption in 2021—twice the global average of 27%. But this is actually an improvement on previous years, its proportion of China’s energy footprint fell by 5.1% between 2007 and 2013, and then dropped by 9.8% in 2014-2021. It is forecast to further decline to 51% by 2025.

The proportion of oil in the primary energy mix has declined more slowly, from a peak of 22% in 2000 to 18.5% last year, while natural gas grew its share from 2.2% to 8.9%. Over this period, renewables have surged, rising from 1% in 2012 to about 7.2% last year, and the share of non-fossil fuels—including hydropower and nuclear—in the energy mix reached 17.3% in 2022 and is expected to grow to 25% by 2030.

While the share of coal has declined over the years, absolute consumption has grown, from 3.91 billion tons in 2017 to 4.02 billion tons in 2019, due to the growth in overall energy usage. China experienced widespread power shortages in 2021, which required more coal to shore up energy security—provincial economies approved the construction of 8.63 GW of coal power in the first quarter of 2022 alone, nearly half the 18.55 GW endorsed for the previous year.

“Coal power plants have not been profitable for a long time now,” says Hu Min, principal and co-founder of Beijing-based public policy consultancy IGDP. “They’re getting the green light from a political and energy security perspective, rather than from a climate or economic standpoint.”

Coal is also integral to several provincial economies. Two-thirds of China’s approved coal power capacity from the start of 2021 to the end of Q1 2022 was concentrated in the six provinces of Hunan, Shaanxi, Gansu, Anhui, Zhejiang and Fujian. Coal production meanwhile, mostly takes place in the three northern provinces of Shanxi, Shaanxi and Inner Mongolia, which mined 72.5% of the 2.19 billion tons extracted nationally in the first half of 2022.

Such coal dependence highlights the contradiction between climate and decarbonization goals on one hand, and economic stability and energy security on the other. “These provinces still really struggle to walk the fine line between decarbonizing and supporting economic growth,” says Lin. The national government has not set out specific provincial goals so provincial governments are left to decide how to approach emissions reduction.

For Hu, the issue is more about adaptability. “Every healthy economic structure needs to be diverse. With or without the dual carbon goals, these provinces need to worry about their economic structure.”

But the heyday of coal as China’s cheapest energy source ended some years ago. Independent research has determined that renewable power is already cheaper than coal in China—an onshore wind farm built today would undercut a new coal power plant on price. Average power generation costs for renewables have been falling steadily for years, with solar dropping from an average of $91.50 per megawatt-hour (MWh) to around $52, with similar cuts for wind power generation. In contrast, coal-fired power cost around $73 per MWh in 2022.

At this point nuclear power is the cheapest energy source at $33.50 per MWh, and it is a key pillar of China’s fossil fuel-free strategy. In April 2022, the national government announced the construction of six new reactors.

The 14th FYP calls for an extra 70 GW of nuclear power capacity to be installed by 2025, and half of the reactors under construction in China have been approved in the past three years. China currently has 55.78 GW of nuclear capacity and the China Nuclear Energy Association has forecast this to more than double by 2030.

Clean colossus

In the midst of all of this, China has become the renewable energy superpower, the biggest solar and wind energy producer by far. By the end of June 2022, China boasted one-third of global solar capacity, and also 342 GW of wind capacity, together accounting for 27.8% of China’s total installed power generation. Forecasts indicate renewable capacity will scale up massively again in 2022—modest predictions see 144 GW added this year.

“Going green is definitely the policy direction and goal,” says Yan Qin, lead carbon analyst at financial software and analytics company Refinitiv. “But energy security issues are emphasizing more than ever that coal will remain the mainstay for a while.”

Other than shifting the balance of energy production, China has embraced new energy vehicles (NEVs)—hybrid and battery electric vehicles—to lower emissions. Chinese cities were early NEV adopters as they sought to clean up emissions from public transport to improve air quality. China’s operational fleet of NEV buses surged to two-thirds of the total bus fleet by 2020. The 14th FYP for green transport in January 2022 called for the share to hit 72% by the end of 2025.

Ongoing urbanization—targeted to reach 65% of the population by 2025 compared with 60% in 2020—means buildings and the built environment are a focus of decarbonization too. By one estimate the construction and demolition of buildings in China was responsible for nearly a fifth of the country’s carbon emissions in 2015.

The Beijing Winter Olympics in early 2022 provided a platform for China to underline its low-carbon commitments. The government invested heavily to ensure a climate-friendly sporting spectacle—all new venues were built to the highest national sustainability standards, and all venues were powered by renewable electricity for the first time in Olympic history. “The Winter Olympics was a showcase for what China’s future zero-carbon energy system could look like,” says Lin.

Green financing

China is counting on the firepower of its immense financial system to fund the decades-long transition to a net-zero carbon economy. The country has embraced green finance, but while green bond issuance more than doubled last year, the amount of capital is still only a fraction of what is needed to meet the multi-trillion-dollar cost of the transformation.

According to China’s central bank governor Yi Gang, China needs to invest RMB 2.2 trillion per year this decade to cap carbon emissions and then RMB 3.9 trillion per year between 2030-2060 to fully achieve carbon neutrality. The RMB 809 billion of green bonds issued by industry and local governments last year amounted to slightly more than one-third of what is currently needed.

China’s green finance market also suffers from a lack of transparent data and poor information quality, which has complicated efforts by domestic banks and other institutional lenders to assess projects seeking green funding. Four companies were criticized by environmental officials in March 2022 for falsifying carbon data.

For these reasons, de Boer says the reliability of the Chinese green finance market is hard to gauge. “I am a bit worried that there could be quite some greenwashing going on,” he says. “There needs to be more disclosure around this, to get a sense of how effectively this money is really being deployed.”

Official support

Xi’s announcement on the dual carbon goals two years ago was the strongest political signal yet that China would accelerate its climate efforts, and it has since been confirmed as a top policy priority.

“China’s climate pledges are serious and that has triggered a top-down all-of-government response: targets, planning, projects, funding… it all adds up,” says Hu.

These political incentives have driven decarbonization of highly-carbon-dependent sectors into a new era, spurring related government agencies such as the powerful National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and Ministry of Industry and Information Technology to push forward the agenda.

In a sign that China’s clean energy economy is maturing, Beijing has been gradually removing fiscal subsidies on renewable energy sources, NEVs and other green industry areas. In August 2021, China ended central government subsidies for new solar power plants, commercial rooftop solar projects and onshore wind farms.

This does not mean fiscal policy support has slackened. In May 2022, the Finance Ministry and State Tax Administration released guidelines for supporting key climate targets and green development, which include measures such as fiscal funds, tax incentives and preferential tax policies.

Backsliding

The question is whether all these measures will be enough given the significant headwinds. According to official data, the economy barely avoided a contraction in Q2 as GDP growth slipped to 0.4% year-on-year, a massive step down from 4.8% in the previous quarter.

More recently, China’s zero-tolerance policy toward COVID-19 has severely disrupted supply chains, including those in the energy industry. The strategy has seen multiple provincial and municipal lockdowns over the past two years, hitting some energy industries such as NEV production and coal mining.

There has been a degree of policy backsliding, too, most visibly in the 14th FYP for renewable energy released in June. The plan set a target for renewables to make up more than 50% of new power demand during 2021-2025, but this was down from a previous expectation of two-thirds given by an National Energy Administration official in March 2021.

Lin is sanguine though, arguing that the downgrade reflects short-term concerns about hedging energy security, and leaving space for more coal power if needed. “It depends on how quickly power demand grows,” he says. “But I think it’s quite likely if we see somewhat lower electricity demand growth, that renewables can surpass that 50% share of additional electricity.”

Climate champions

For all of Beijing’s policymaking, the job of actually curbing China’s emissions lies mostly with businesses given that 98% of China’s emissions come from industry, power generation and transport. Qin says the most important corporate stakeholders are China’s centrally-administered state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which include its big five power utilities, three national oil companies, two nuclear power developers, two grid operators and the world’s biggest coal mine operator.

“There’s no doubt the central SOEs will be the most important in helping fulfil the carbon pledges,” says Qin. “No one else can carry out such a vast scale of renewable investment.”

But private players will also have a key role in certain niches. Fujian-based Contemporary Amperex Technology (CATL) is already the global leader in manufacturing EV batteries, supplying the critical component to almost all of the world’s automakers including Tesla and Volkswagen.

China’s ranks of domestic EV carmakers such as Nio and BYD will also be important as the road fleet becomes increasingly electrified. They stand to expand globally too, as consumer demand for EVs overseas catches up with China—Nio opened its first overseas plant in Hungary in September 2022.

China’s clean energy industries are also having a global impact in other ways. Leadership in renewable energy generation means homegrown solar companies are supporting buildout in the rest of the world. Chinese solar equipment exports more than doubled year-on-year to $25.9 billion in H1 2022, not far off the $28.4 billion exported for all of 2021. A tightening ban in the US on certain solar equipment shipments from China has prompted some Chinese manufacturers to set up factories in Vietnam to evade the crackdown, according to Shan Guo, co-founder and partner at consultancy Plenum.

“Renewable energy is the product that every country wants to have more of, including the US, so Chinese solar companies are building capacity in Asian countries to be able to export there,” says Guo.

China is also leveraging its multi-trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), whose 143 members made up 29% of global emissions in 2019. Green energy has become the new focus of the BRI—solar, wind and hydro comprised one-quarter of China’s energy investment in BRI members in H1 2022, while cleaner-burning natural gas made up 56%. Recent research also suggests Chinese direct investment has helped BRI countries clean up, with every 1% increase in investment shaving 0.02-0.04% off emissions.

In September 2021, under international pressure before a major UN climate change conference in Glasgow, Xi committed China to no longer fund construction of new coal-fired power projects overseas. The move was a step in the right direction but “does little to change the domestic picture”, says Qin. “A lot of the affected projects had actually already been stopped because the host countries are becoming more conscious of net zero as well.”

Getting back on track

It is not an exaggeration to say that successfully dealing with climate change globally depends upon China, and while efforts to reign in emissions continue, its near- and long-term climate targets appear to have been overtaken for now by more immediate worries. There is little prospect of meaningfully slowing global warming and preserving a livable world unless Beijing goes green far more aggressively than it currently plans.

“China must get it right or else we can’t achieve this goal,” says de Boer. “There’s simply no way to solve climate change without China’s leadership.”

“Climate has never been the sole top priority for China even though it has been working to decarbonize the economy for a long time now,” says Hu. In recent years, climate change has acquired a political dimension because it is often linked with geopolitics—an example being Beijing’s suspension of US-China climate diplomacy in response to US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August 2022.

An unwillingness to separate climate issues from geopolitics points to conflicting priorities. “China’s climate ambition still needs to be translated into a solid long-term action plans towards 2050,” says Hu. “If that happens, it may be the peak moment for showcasing political support for climate goals.”