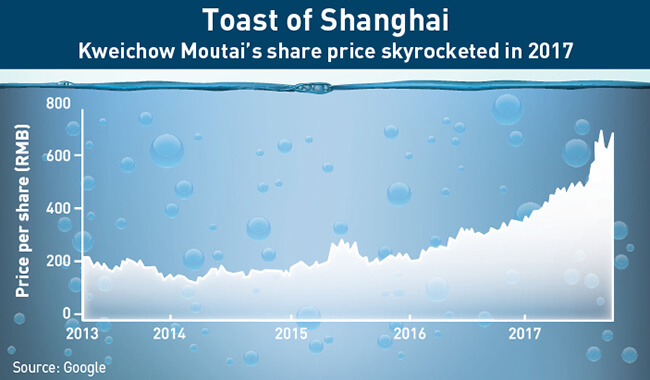

The Chinese government’s 2013 anti-corruption campaign was a sucker punch for liquor maker Kweichow Moutai, which saw its share price halve over the next 12 months. But in 2017, the company pulled off an amazing fightback

It’s a comeback story worthy of a Hollywood blockbuster. Three years ago, China’s once all-powerful liquor maker Kweichow Moutai looked to be on the ropes. President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign had dealt a vicious blow to the country’s most famous spirit brand—for years a staple on every government banquet table—and the company’s profits and share price had taken a hammering. By January 2014, Moutai’s shares were worth just over RMB 119 ($18.31) per share—a fall of 50% in 14 months. With no end to the crackdown in sight, some questioned whether the legendary distiller would ever recover.

Yet last April, Moutai completed an extraordinary rally by knocking Diageo—owner of many famous brands, including Johnnie Walker—off its perch as the world’s most valuable liquor company. By mid-December, the Chinese brand’s share price had surpassed RMB 650 ($100), making it the most expensive stock on the Shanghai board.

The company’s renaissance has not been without controversy. For some, Moutai’s recovery was a sign that Wang Qishan, the Chinese Communist Party’s anti-corruption czar, was taking his foot off the gas. Others painted the company’s success as a triumph of smart rebranding born of necessity with Moutai tapping China’s rising middle class. In November, the country’s state newswire, Xinhua News Agency, even took the unusual step of warning investors that the spirit brand’s skyrocketing shares were “liquid gold,” suggesting that the rise was being fuelled at least in part by speculation.

How did Moutai pull off its amazing fight-back? As with so much in China, there is more to this story than meets the eye.

National Spirit

Moutai’s fall from grace was even more dramatic given its unique status as the country’s number one brand of baijiu, the strong spirit made from sorghum. Famous US reporter Dan Rather once described baijiu as tasting like “liquid razor blades.”

“Moutai’s brand is very strong,” says Derek Sandhaus, author of the book Baijiu: The Essential Guide to Chinese Spirits. “There’s not a good comparison in the US, because we don’t have state-owned enterprises or a spirits market that is so dominated by one category of spirits as China is by baijiu.”

Chinese drinkers’ love for baijiu almost cannot be overstated. In 2016, the Chinese drank an incredible 1.21 billion cases of “national spirits,” according to beverage market analysts IWSR. This gave all national spirit brands, including Moutai, a 99.6% market share in the country’s liquor market.

The term “national spirits” encompasses many traditional Chinese alcoholic beverages including huangjiu, which is the main drink in many parts of southern China. But baijiu is the most popular nationally. The reason for this lies in China’s modern history, Sandhaus explains.

“[Baijiu] was much more potent than what preceded it, huangjiu, and it was… much cheaper. Both factors endeared it to the Chinese peasantry, while the aristocracy continued to prefer huangjiu,” says Sandhaus. “After the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949, the proletariat’s elevated status lifted the fortunes of their favorite drink.”

No baijiu brew was elevated quite as high as Moutai. The Communist leader Zhou Enlai is said to have acquired a taste for the drink in the 1930s during the Long March, as the Red Army was traipsing across Guizhou province in China’s southwest to escape Chiang Kai-shek’s forces. After the Communists won the Civil War and Zhou became China’s premier, he insisted that Moutai be served at every state dinner.

Later, when China entered its era of rapid economic growth, demand for Moutai began to soar among ordinary consumers, who wanted a taste of their leaders’ preferred drink. “As a college student I used the money from my first internship to buy a bottle of Moutai for my father as a [Chinese] New Year’s gift,” says Wang Wenjian, a Shanghai-based media worker. “My father took a long time to finish the bottle, as if he wanted to enjoy every drop of the national spirit.”

By 2012, Moutai was unable to keep up with the rising demand. The price of one bottle of the spirit rose to above RMB 2,000 ($300), and the company posted year-on-year net profit growth above 50%.

Though an expanding middle class contributed to this trend, a large number of the famous white-and-red bottles were still ending up on government banquet tables. Some analysts estimate that Chinese government entities were responsible for 50% of all Moutai sales at this point.

As a result, when Xi Jinping came to power in late 2012 and launched his famous anti-corruption campaign, demand for Moutai plummeted. One distributor who acts as a middleman between Moutai and retailers in Guizhou province, who wished only to give his surname, Huang, says that he was under tremendous pressure from 2013 to 2015.

“The wholesale price at one point dropped to RMB 830, while the price we get from Moutai is RMB 819,” says Huang, adding that the wholesale price has since recovered to RMB 1,530.

Moutai felt the pinch too. Its net profit growth rate languished at around just 1% throughout 2014 and 2015.

Reinvention or Relapse?

But what looked to be a lasting blow turned out to be only a glancing one. In October, the company announced that its net profits for the first nine months of 2017 were up over 60% year-on-year, sending investors into frenzy. The company has been quick to paint its recovery as the

result of a deliberate reinvention.

“Over the past few years, we have taken measures to shift Moutai from government consumption to business occasions, family, casual and personal uses,” said Yuan Renguo, Chairman of Kweichow Moutai Co Ltd in a recent statement on the company’s website.

Moutai has invested heavily to make its brand more visible. The national spirit has become the national timekeeper, shelling out a huge amount for a premium ad slot just before the start of Chinese state broadcaster CCTV’s flagship news program. As the clock ticks down to 7 p.m. each evening, a booming voice announces, “National baijiu Moutai broadcasts the time for you.”

This autumn, the distiller even opened its own college and airport in its home province of Guizhou. The group also plans to build a luxury hotel in Sanya, the popular tourist resort in sub-tropical Hainan province, as well as launch baijiu tasting and “story telling” events to spread baijiu culture.

How effective these ventures have been in branding terms is open to question, but there is no doubt that there has been a change in Moutai’s customer base since 2012. “Corporate demand now accounts for more than 50% of Moutai’s consumption, according to our interviews with distributors,” comments a Shanghai-based fund manager, who declined to be named in this article due to the sensitivity of the topic, adding that demand from the government has fallen to around 20%.

According to one distributor quoted by a China Merchants Securities report, this shift toward private consumption may simply be a natural result of the increased spending power of Chinese consumers. “The middle class is expanding faster and faster with the addition of 10 million people ever year, and they are demanding more Moutai,” the distributor says.

But others doubt whether this is the whole story. “Moutai is still playing a major role in government banquets,” says Tony Zhu, a well-known Chinese food and beverage industry analyst. “Demand from private banquets is rising but it’s not enough to support the recovery of Moutai.”

The Shanghai-based fund manager also expressed skepticism that middle-class consumers were solely responsible for Moutai’s return to bumper profits, speculating that government officials may simply have started drinking baijiu on their own time. “According to what we have learned from distributors, government officials can’t pay the bills [directly any more],” he says. “Before, they could purchase it and claim it as expenses. Now, they seldom do that. But drinkers, they don’t just disappear, so they get to the spirit in another way.”

The fund manager added that he believed Moutai’s recent investments in Guizhou were more about currying favor with the government than about rebranding. “Moutai doesn’t need to promote itself at all. I look at all these things it has done as its way to support the local economy and contribute to CCTV,” he says.

On the other hand, Moutai’s sales and profits have continued to grow strongly since late-2015 even as local governments have introduced even tighter restrictions on officials’ behavior.

Boom and Bust

Another factor that made the boom, crash and subsequent recovery in demand for Moutai look even more extreme was that in the run-up to 2013, the premium liquor essentially became an investment, a true “liquid gold.”

“There was clearly a bubble in 2012, as many people were just buying [Moutai] to hoard and speculate,” notes distributor Huang. As a result, when the price of Moutai crashed in 2013, there was a huge glut of baijiu sloshing around the market, which applied further downward pressure on prices and demand.

Moutai’s price has always been unusually volatile because of its long, complex production process. Unlike other brands of baijiu, Moutai takes at least five years to make, needing to be distilled nine times and aged three years. This means that it is difficult for Moutai to react to market changes as it takes years for any drop in production to filter through to the market.

Now that inventory levels have declined and demand has increased, the company’s lack of flexibility is likely to keep prices high. “Moutai will at least stay robust for another three years, as Moutai’s production can hardly meet market demand and it’s unable to expand production quickly,” says Huang.

The liquor’s price is expected to rise to around RMB 1,800 as Chinese New Year approaches, when Moutai will be served at family reunions and banquets across the country. But Huang does not expect another bubble to form, at this point at least. “I don’t see many people hoarding Moutai as there isn’t a big profit you can expect,” he says. “You buy it from a supermarket at around RMB 1,700 and I don’t expect it to rise back to the 2012 peak of RMB 2,000.”

Keeping China’s Glasses Filled

With demand at a healthy level, Moutai looks set to continue growing its revenues and sales for some time. In November, the company announced that it planned to sell 28,000 tons of Moutai in 2018, up from 26,000 tons for 2017. But China Merchants Securities has estimated that Moutai is on track to sell more than 30,000 tons in 2017.

Whether the company can continue that kind of growth long-term is another question. Sales are still overwhelmingly going to Moutai’s core market of mainly men over 40, according to Ben Cavender, Principal at China Market Research Group. “Younger consumers do not place the same cachet in the Moutai brand that previous generations have,” he believes. “There is a lot of competition now from a wider range of imported wines and spirits.”

China imported 254 million liters of wine during the first half of 2017, a 13.9% year-on-year increase, according to The Drinks Business. Though this number is still small compared to the consumption figures for baijiu, there are signs that the drinking culture is changing in China. Where once most banquets involved downing shot after shot of hangover-inducing liquor, many Chinese drinkers now prefer a more relaxed approach.

“We don’t drink too much baijiu during business banquets anymore,” says Alex Li, a Shanghai-based entrepreneur. “It is too expensive and unhealthy. We prefer wine now—you can buy quality wine at just a few hundred yuan.”

On the other hand, there are also signs that Moutai is benefiting from this move away from banquet binge drinking as consumers consider the premium brand to be a healthier, more refined option. “I won’t mind enjoying a bottle [of Moutai] with my friends,” says Li Rui, a businesswoman from Shanghai. “Unlike poor-quality baijiu, the good baijiu won’t give you a headache.”

Tony Zhu has noticed a similar trend. “Chinese consumers are redefining their understanding of baijiu,” he says. “Drink less and drink better is their new motto.”

What’s more, Moutai’s core demographic—Chinese over-40s—are becoming wealthier and more numerous every year. “Younger generations drink less baijiu, but it’s unclear how great the long-term impact of this will be,” observes Sandhaus. “Drinking consumption has always been tied to professional success in China, thus those at the beginning of their professional careers now may drink more baijiu as their careers advance.”

All this suggests that Moutai’s sky-high share price is largely justified, although its high price-to-earnings ratio, 34.1 as of December 12, 2017, is making some analysts jittery. “I don’t think it’s smart to buy into Moutai stock at this level,” warns another fund manager in Shanghai, who also wished to remain anonymous. “There might be space for gains in the stock, but I see more risks in buying such an expensive stock.”

Cavender has a similar view. “I think we may see share prices continue to go up over the course of the next 12 months,” he comments. “But gains will probably be because of overall retail investor confidence in the market and because more foreign investors are likely to invest in a broad range of stocks as they become included in the MSCI index.”

If this view proves correct, Moutai could continue its reign as undisputed champion of the global liquor market for some time to come.