A large portion of rural Chinese incomes come from remittances sent home by migrant workers

As China’s rural-urban migration has increased over the past decades, so has its rural-urban divide. Remittances sent back to those remaining at home have grown into a large portion of rural incomes, with almost $51 billion sent home in 2022 alone, but recent research by Wuhan University suggests that more needs to be done.

“China is currently undergoing an unprecedented urban-rural integration,” said the report. “However, due to a mismatch between household income and expenditures, an urbanized lifestyle in rural areas is facing a dilemmatic trap, a pseudo-middle-class life.”

As the country’s rural-urban divide grows, so does the risk of China getting stuck in the middle-income trap. Effectively closing the gap is key to the country’s development, especially given that China is also facing multiple economic headwinds. But while increased urbanization offers solutions, it is not the only option, and sustainable development of rural areas must be sped up.

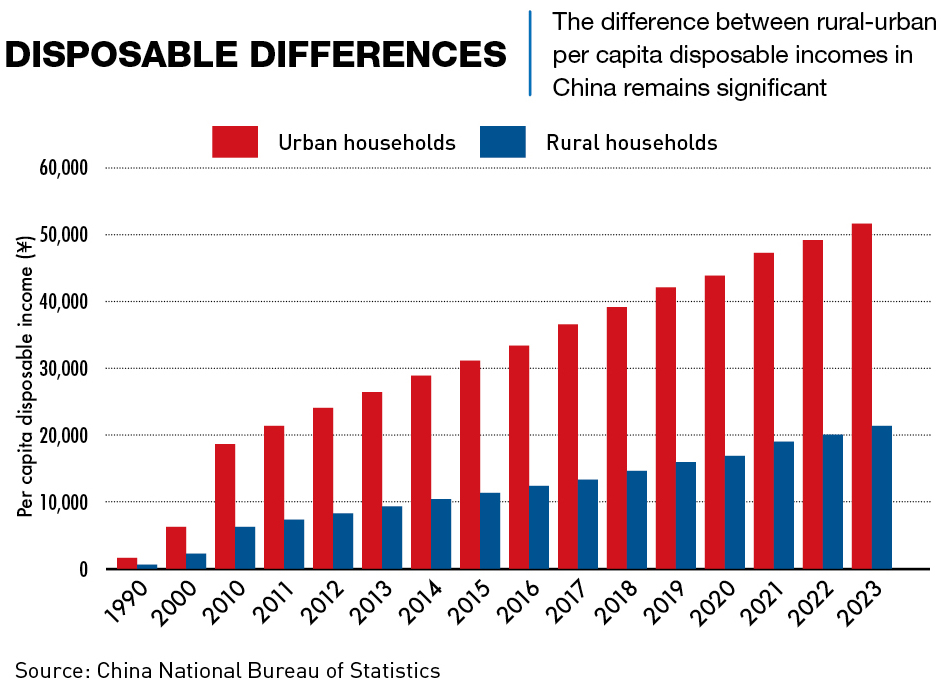

“Despite, or perhaps because of, the country’s increase in overall wealth in recent years, China now has one of the largest rural-urban income gaps in the world,” says Martin K. Whyte, John Zwaanstra Professor of International Studies and Sociology, Emeritus at Harvard University. “And it isn’t just income, there are large gaps in other areas which can have a compounding effect on how the country develops.”

Aiming for urban

The Chinese government has been pushing to increase urbanization levels since the 1980s, and by 2023 the country had reached 66%, compared to 83% in the US. Still, there has also been an uneven level of economic development between China’s rural and urban populations.

The late Premier Li Keqiang described China’s approach in 2012, saying “Urbanization is not about simply increasing the number of urban residents or expanding the area of cities. More importantly, it’s about a complete change from rural to urban style in terms of industry structure, employment, living environment, and social security.”

While China’s urbanization rate has jumped significantly over the years, there is a long way to go before Li’s goal of a complete change in style is achieved in rural areas. Also, the Chinese definition of urbanization is exceptionally broad, and includes swathes of rural areas around major cities, as well as rural residents who work in non-agricultural roles.

“You really have to split the 66% urbanization rate into higher and lower quality urbanization,” says David Fishman, Senior Manager at professional services firm The Lantau Group. “The country still has quite a way to go before it reaches an urbanization level commensurate with developed nations, and China is well aware of this. China is very clear that it classifies itself as a developing nation, and while cities like Shenzhen and Shanghai don’t fit that bill, if you really get out into rural areas, it is clear to see that the country is still developing.”

Around 900 million people in China are classed as urbanized, a little more than 110 million of those are in first- and second-tier cities. That leaves around 800 million in various states of urbanization, from huge megacities all the way down to tiny villages. Add to that the 500 million classed as rural and it is clear that much development is yet to be done.

Mind the gap

The disparities between rural and urban areas of China can be quite pronounced, with a general economic focus on the Eastern regions leaving many other provinces less well-off. This has become more pronounced with recent economic headwinds, especially the dismal performance of the property market and land sales, which have historically made up the majority of local government finance generation.

Zhejiang province, on China’s east coast, is home to many large cities and businesses, and has a GDP per capita of around ¥125,000 ($17,275). In the northwestern province of Gansu, one of the country’s poorest, that number is just ¥45,000 ($6,185). This results in gaps in services such as healthcare and education, and low levels of potential for new business ventures.

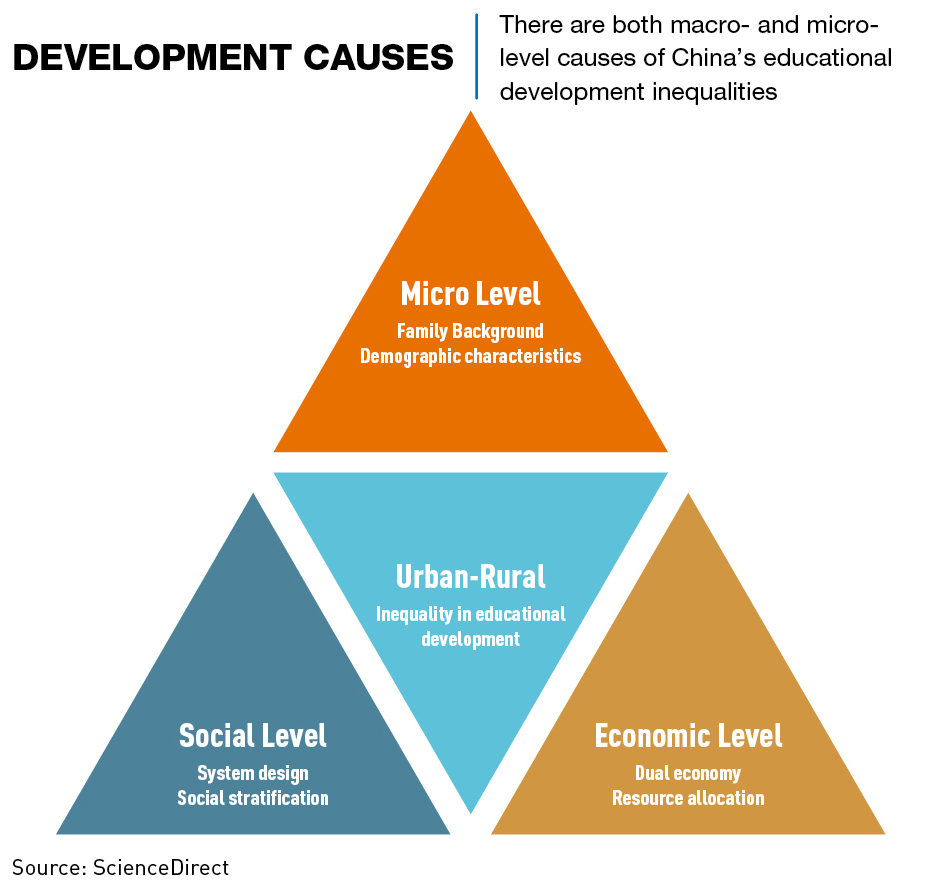

Lack of access to quality education can have a lifelong impact on a person’s job prospects. “One of the reasons that China has been so successful in areas like solar panels has been because of those going through the urban education system,” says Whyte. “Many have experienced a quality of education that has allowed them to work and innovate in companies that are competing at a world-class level. But this is less the case for the majority of young people who have a rural hukou, and that might dampen overall innovation in the long run”

The gap in access to healthcare and other services across the country can also have an impact on quality of life or ability to work. While the poorer rural areas and smaller cities have a theoretically high growth potential, the working-age population must be healthy and well-educated.

In 2021, the Chinese government announced that it had eradicated extreme poverty in the country, which was followed by a Common Prosperity goal aimed at raising the prosperity level of the masses, largely in rural areas. But as Li Keqiang had noted a year earlier, there were still 600 million in the country with monthly incomes of less than $140. This shows that although many people have been lifted out of poverty, rural living conditions haven’t reached what many would consider as ‘common prosperity,’ especially when compared with their urban counterparts.

Private companies in rural areas still face financing difficulties and banks and financial institutions are more cautious about lending to rural enterprises, citing higher risks and lower returns compared to urban ventures. In addition, there have been issues with over-investment in short-term trends that leave those in rural areas worse off.

“There is a real need for outside capital to come in because it is often the case that the locals in an area don’t have the capital required to start a business and also lack anything to use as collateral,” says Fishman. “Tourism is one of the major opportunities in some rural areas and there are several examples of investments made that have left people vulnerable, whether that be because of COVID, a shift in demand trends, or even just a too-optimistic operation projection before putting money in.”

There are many reasons for the lack of parity between rural and urban areas in China. The government’s development policy has over the decades focused on the coastal areas with local government spending driven by centrally set priorities. This is why there have been successes in areas such as the Yangtze and Pearl River Deltas, with innovation zones driving economic development.

But for some provinces, there is a disparity between capabilities and government-set targets. In rural areas, there is lower consumer demand and a lower level of innovation and entrepreneurship, which in turn leads to lower commercial investment. Thus, rural areas rely heavily on government subsidies, and this dependency can create vulnerabilities, particularly if policy or funding priorities change.

“It ultimately relies on local economic development levels and how well the economy is determining how much money can be spent on certain priorities,” says Justin Wang, head of LEK Consulting’s China practice. “Taking healthcare as an example, for the eastern parts of China where the money is flowing, they have reached the point in the priority list where rural benefits are being considered more. But if you look at places that are struggling with their industrial output, how much money can they actually spare for these things?”

Bridging the gap

There is no one-size-fits-all solution to closing the rural-urban divide in China, and a variety of different approaches must be used simultaneously.

“The simplest solution is to aim for 100% urbanization, moving everybody from rural areas to cities, but that is obviously not sustainable,” says Fishman. “So, what to do instead? China has to be able to either make the urban lifestyle accessible to rural populations, or make the rural lifestyle attractive, and actually worth sticking around for. Because unless you figure out complete automation of food production, you need people there.”

Migrant workers from rural areas are the backbone of China’s economy. This acts as a dual-positive, both labor for the urban markets, and also increased income for citizens in rural areas by virtue of migrants sending money back home to their families. Given its benefits, facilitating rural-to-urban migration makes sense for the government, but a major barrier is the household registration system.

All Chinese residents hold a hukou—an official document certifying residency of a particular place—which determines access to social services, including healthcare and education. If you hold a rural hukou, you can live in a major city for decades but never obtain a local city registration.

“The hukou system is behind so many of the difficulties migrants face,” says Scott Rozelle, the Helen F. Farnsworth Senior Fellow and the co-director of Stanford Center on China’s Economy and Institutions at Stanford University. “It limits access to healthcare and education opportunities and means that parents often have to leave children behind when they migrate, which also has effects on their development.”

“For my children and many others, the difference between a rural and urban hukou on their education was huge,” says Lily Wang, a migrant worker from Anhui who now lives and works in Shanghai. “Cities have a large number of good schools in each district, while the choice in rural areas is very limited. Getting an urban hukou meant they could get a huge increase in educational opportunities.”

Steps have been taken to relax the hukou system in some areas of the country and equalizing urban benefits could transform the lives of up to 180 million migrants. It would enable them to access basic services and social welfare tied to their hukou.

“There has been an increasing tendency in the last decade or so for the percentage of people in formal sector jobs to shrink and the number of people that are in informal jobs to rise,” says Whyte. “Those in the informal sector are mostly migrant laborers, working in the gig economy, and are mainly not urban hukou people. And when things like COVID come along, it’s disproportionately migrant laborers who are laid off.”

In July 2023, Zhejiang province removed household registration requirements everywhere but in the provincial capital of Hangzhou. A month later, China’s Ministry of Public Security announced the scrapping of registration requirements for all cities with a population of 3 million or less and a ‘significant relaxation’ of requirements in cities with populations between 3 and 5 million.

The idea has considerable backing in Beijing. Former People’s Bank of China (PBOC) governor Yi Gang said in September 2023 that hukou reform should be advanced as research has shown it could boost consumption among migrant workers and new arrivals by 23%.

Lily Wang is one of those who have benefited from a change in hukou, having converted her rural hukou to an urban one. “Relatively speaking, it is a bit easier to get the hukou now and that gives people access to more job opportunities and more money,” she says. “To me, it feels like smaller cities can’t offer these benefits at the moment.”

Outside of migration to top-tier cities, the other solution to bridging the rural-urban gap is developing smaller cities and rural areas. The ideal outcome is not to require people to stay in rural areas because it is their only choice, but to actually make them attractive places to live and work.

“You can allow more people to access urban infrastructure and you can improve the rural infrastructure at the same time, it’s not a dichotomy between urban and rural all of the time,” says Fishman.

In recent years, the Chinese government has promoted rural revitalization as a key part of the country’s development strategy. Agriculture, rural areas and farmers have become a top priority for the Chinese government. This includes pushing the adoption of modern farming practices by small-scale farmers, increasing the quality of rural incomes and purchasing power, and boosting the creation of agricultural brands.

Down to business

Aside from increased service access, there is also the need to increase incomes through the creation of quality jobs, and this is where China’s businesses have an opportunity to play a role. Much of the work done on improving China’s rural areas has so far been done by local governments, and there is still a lack of private enterprise involvement in these areas.

As far back as 2015, Jack Ma’s fintech firm Ant Financial began to facilitate small-scale investments by rural citizens through its Yu’E Bao accounts, and more recently Ant-backed online bank MYBank, which offers an online payment system, announced plans to serve 2,000 rural Chinese counties by 2025.

For businesses, urban areas offer excellent market access and infrastructure, high-quality talent pools, and a much larger potential for greater return on investments. Addressing the skills gap requires long-term investment in education and training, and by upskilling rural populations, businesses can create a more capable workforce while stimulating local economies.

“You can build a whole lot of infrastructure, but you can’t necessarily create the jobs until actual consumption is headed that way and this is where the concurrent development of small cities and rural areas can be difficult,” says Fishman. “The smaller cities are still going to draw people away from rural areas because there is consumption there, and in turn, jobs.”

Tailoring products and services to meet the specific needs of rural consumers, as well as leveraging technology, has proven successful for some companies. E-commerce platform Pinduoduo, for example, connects farmers and manufacturers directly to customers through the use of group buying, in which consumers team up to buy products in bulk. This increases both the buying power of rural consumers, as well as boosting direct income for those making the product.

Local healthcare outposts are also increasingly able to offer video consultations with doctors at top-tier hospitals in major cities.

“The private healthcare industry has an opportunity to assist with general health issues in areas across China,” says Wang. “If you have something severe, most people may consider going to a public hospital, but in terms of less severe diseases and check-ups, private businesses are already quite active in providing these services.”

But who pays for these services remains an issue. Centralized help is still required and engaging with local governments and taking advantage of rural development initiatives can provide businesses with valuable support. These partnerships can lead to subsidies, tax incentives, and necessary infrastructure improvements.

Searching for style

Solving the problem of China’s rural poor, as highlighted by the late Premier Li, is key to the country’s economic future and making sure it escapes the middle-income trap. There are enormous gaps in the market in China’s rural areas that could serve as fertile ground for private enterprise investment, but the fundamental issue remains that it simply is not yet profitable for businesses to operate in these areas, meaning that basic development must come first.

“Given the fairly ruthless requirements of private capital, there is still a need for government intervention in these areas first,” says Fishman. “There are certainly opportunities, but the risks of lending to what is still quite a vulnerable population might be too much right now.”

As China continues its journey toward modernization, the convergence of rural and urban economies will be a defining narrative, shaping the future of many businesses, as well as society as a whole.

“The real crux is the ability to pursue gainful employment for working-age people that can support your family,” says Fishman. “Without increasing the ability to do so in rural areas or smaller cities, it will be difficult to close the gap.”