China is suddenly worried that it doesn’t have enough people. In a meeting of the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission in May 2023, Chinese leader Xi Jinping stated that “population development is a key issue for the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” The statement comes as the country faces an unprecedented combination of demographic issues that could potentially have serious economic ramifications.

Chinese authorities have since announced they will take measures to stabilize employment levels, improve the quality of the labor force and ensure a solid supply of jobs. China was just overtaken by India as the world’s most populous country, and the population graph will only go down from here if current trends continue. The demographics trap is easily China’s biggest long-term issue, and while there might not be much of a noticeable effect in the short term, any solutions will need a long lead-in time to take effect.

The country needs to actively address the problem to shore up its economy and avoid getting stuck in the middle-income trap, and changes need to happen soon. While attempting a return to population growth would be the traditional approach, the impact of technology, and in particular AI, might provide another way for the country to keep its economy on track.

“China has quite a problematic mix of demographic issues facing them,” says Michael O’Hanlon, Director of Research, Foreign Policy at The Brookings Institution. “There are other countries around the world that are facing similar problems, but China still has huge ambitions and wants to do big new things, and that’s going to be hard if [current] trends continue.”

People power

A growing population has throughout history been seen as a key factor to the development of an economy. Other countries around the world, such as Japan and Hungary, are also facing shrinking populations, but many of them have avoided the middle-income trap and reached an average level of prosperity well above China’s today. Populations tend to shrink once a certain level of financial success has been reached, but for China the decline has started early and the middle-income trap yawns.

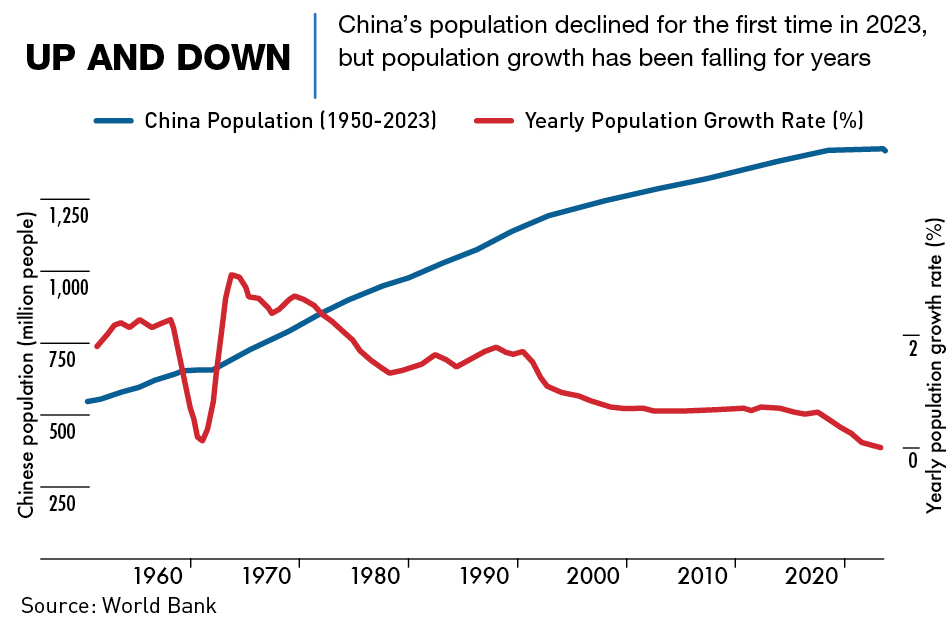

China’s population declined by 850,000 people in 2022, the first fall since the early 1960s. And while it is now the second-largest economy in the world, China only has a GDP per capita of around $12,500, well below the level of Japan or South Korea when their population growth went negative—each had per capita GDPs of $35,991 and $34,997 respectively at that time.

The decrease is expected to continue in 2023, but it is unclear by exactly how much as 2022 may have been something of a statistical outlier. “The COVID-19 lockdowns and subsequent deaths from infections at the end of the year made both having new children harder and the death rate higher,” says Xiaolin Shi, Assistant Professor of Economics at Northeastern University. “Additionally, cultural issues might have had an effect on birthrates due to parents waiting for 2024, which is the year of the Dragon, with babies being born in such a year being deemed stronger, braver and luckier than others.”

While there may be some merit to this explanation—birth rates across Asia have historically dropped in the year of the Tiger and risen in the year of the Dragon—the country’s population growth had been trending downwards in previous years and a declining population is not the country’s only demographic issue. Marriage rates are also declining. The number of couples married in 2022 was down 10.5% on the previous year and marks a record low since 1986 when China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs began releasing statistics. Fertility rates have also dropped.

“The infertility rate is increasing as the age of marriage and childbearing is delayed,” says Fuxian Yi, author of Big Country with an Empty Nest. “The age of first marriage for Chinese women was 23 in 2000, but increased to 28 in 2020. That has in turn led to the infertility rate increasing from 2% in the early 1980s to 18% in 2020.”

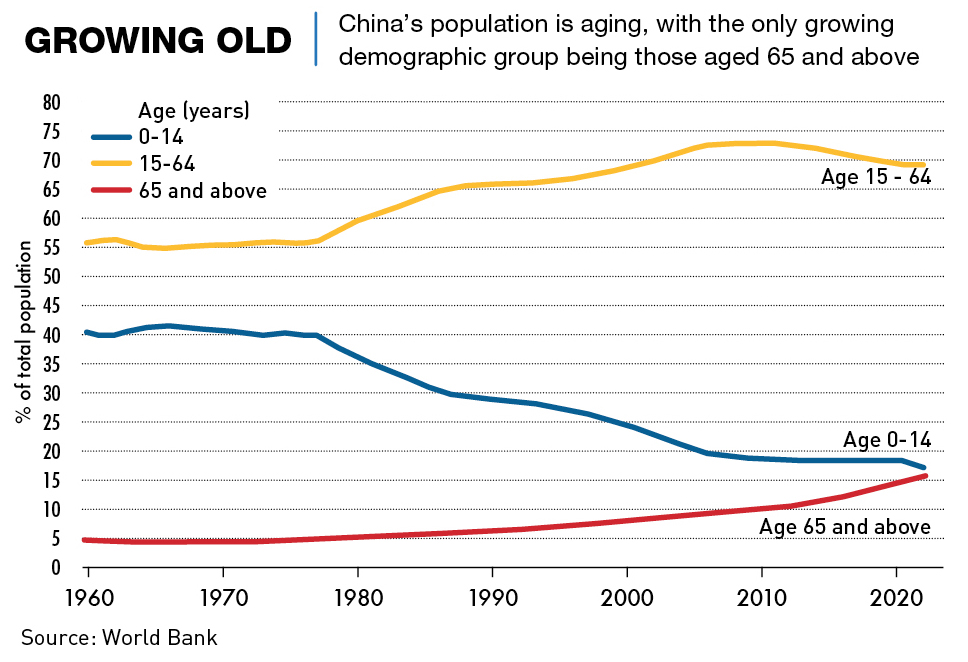

The result is that China’s population is ageing quickly, with the country’s working age population expected to fall by 9% over the next 10 years. “This is obviously not a very good place to be economically,” says O’Hanlon. “Having to spend a lot of money on simply keeping older people alive through medical bills and pensions is going to hamper the production of output for the purposes of raising your standard of living as a country, building up your science and technology base or your infrastructure.”

Unemployment is also high, particularly in the country’s urban youth with record-setting numbers occurring month on month: in May 2023, just over 20% of urban-dwelling 18-24 year-olds were out of work. But at the same, the country is facing a labor shortage in some, particularly blue-collar, industries thanks in general to perceptions that this work is below many who are now qualified with degrees.

“China’s gross enrollment rate in higher education is rising rapidly,” says Fuxian Yi. “But college graduates are reluctant to take up manufacturing [jobs].”

Cause and effect

There are multiple reasons as to why China finds itself in the situation that it’s in. The most obvious are the lasting effects of the country’s erstwhile one-child policy, which for many years kept birthrates well below the 2.1 required to meet the replacement threshold as well as causing the discrepancy between the number of men and women in the country, thanks to the societal preference for male children.

“Decades of China’s intrusive and overbearing family planning policy coupled with anti-religious education have undermined family values associated with traditional beliefs,” says Fuxian Yi. “This has made it socially acceptable, and even desirable, for couples to have one child—or none.” The lack of an uptick of births after the one-child policy’s relaxation and subsequent cancellation in 2016 illustrates this point, with birth rate declines ranging from 3.81% to 17.95% per year from 2017 to 2022.

The rising costs of having children have also been an issue. The competitive nature of the education system in China, for example, means that there is a huge amount of money required for extra-curricular tutoring and classes that parents deem necessary to get their children the right opportunities in life. The recent crackdowns on the after-school tutoring industry was a measure taken to deal with this, but there has been a resurgence of off-the-books tutoring in recent months, indicating that things have not really changed.

“The competitive nature of education in China means that Chinese parents are particularly afraid of their kids falling behind their peers,” says Shi. “So there is something of a rat race in terms of education and a lot of prospective parents now don’t want to get themselves involved in this race unless they are prepared. This means they will avoid having children until they are psychologically, physically and financially prepared.”

Family pressures and filial responsibility are further reasons for a shifting attitude towards marriage and having children. There are minimal social safety nets for Chinese citizens and the absence of a real pension or old-age care requires children to look after their ageing parents. For some, this can be a reason to have a child, to secure their own care, but for many it is a stress that reduces their freedom of choice in life. High-pressure work environments also add to these already out-sized stresses.

While all of these factors are usually more important in Asian cultures, other more global concerns are also helping lower birthrates in China. For example, the idea of bringing a child into a world that is progressively heading towards environmental disaster and geopolitical turmoil is not a choice that some would like to make.

“There are many problems that we’re starting to see now in the world that are only going to get worse unless changes are made,” says Minmin Zhang, a 28-year-old office worker in Shanghai. “I don’t really want to bring a child into a world if it means that they’re going to have to deal with a worse situation.”

Pending problems

Added together, these issues have not only resulted in the first population decline in recent Chinese history, but they also have myriad economic consequences. China is still very much at risk of falling victim to the middle-income trap—a middle-income country failing to transition to a high-income economy due to rising costs and declining competitiveness—because of the economic slowdown and for systemic reasons. And longer-term, the prospects for China’s economy will depend on whether the country can spur population growth, or at least productivity growth.

“China has not fully made the transition to middle- or upper-class living for all of the population,” says O’Hanlon. “And now they have this new set of problems, a lot of people who are still relatively poor, in a country with fewer children to take care of those aging parents and grandparents, and the country hasn’t quite generated the productive output to make it easy to build and fund a social security system.”

Consumer spending-driven economic growth is a major part of the country’s future development plans and with less consumers being born, this becomes less feasible over time. In China, household consumption accounts for only 38% of GDP, compared with 50-60% in the West, and disposable income is 44% of GDP, compared to 60-70%.

“China needs to raise disposable income as a share of GDP to increase domestic demand,” says Fuxian Yi. “But doing so could undermine governmental power, and while it would likely be a benign reform for China’s economy, society and politics, it would probably encounter quite a lot of resistance.”

A lack of demand inevitably has a knock-on effect on business across almost all sectors of the country’s economy. “China needs to make sure that the manufacturing sector does not decline,” says Yi. “Germany, Japan, Greece and Spain are all facing similar ageing, but Germany and Japan have higher economic growth rates than Greece and Spain due to their relatively strong manufacturing sectors. To strengthen manufacturing, China needs to reform education by reducing emphasis on four years of college education and increasing vocational education.”

The education industry will also take a hit that will gradually get worse as the years go by, as fewer children will mean fewer schools, universities and educational institutions. Property developers, which have already been struggling with massive debt issues over the last few years, will also struggle from a lack of demand for housing.

Further, there are other countries that are still growing at a rapid rate which will challenge China’s current supply-chain dominance, potentially taking away more business from the country. India, for example, has already overtaken China’s population in mid-2023 according to UN estimates, and offers a number of advantages over China for foreign businesses looking to expand. China’s competitors all benefit from having lower labor costs, more open foreign policy and a more accessible financial industry.

Growing necessities

Faster economic growth is a necessity for China to maintain its development trajectory and this means the country is really only facing two options. Either it needs to restart population growth or it needs to find a way to increase economic growth without restoring population growth. And the experts are divided as to which of the options is more viable.

The first option, encouraging more marriages and by extension more childbirth, requires greater widespread confidence in the future. This could be achieved with a more predictable and transparent regulatory environment, giving Chinese citizens a clearer path to being able to plan their futures.

“In order to get statistics moving in the right direction, significantly improving a country’s economic prospects appears to be one of two main approaches,” says Ouyang Hui, Distinguished Dean’s Chair of Finance at CKGSB. “The other is the creation of strong government policy support, such as that found in Nordic countries.”

Policy measures aimed at increasing birth rates work best with multiple approaches and the more generous the better. “Sweden’s perennially high fertility rate is, in part, related to its impressive per capita GDP of over $50,000, but even accounting for this, the country’s fertility rate can be considered high,” says Hui. “There are also incentives in place for shortening the time between births, a robust system of childcare services and there is a strong support system that allows parents to raise kids without interrupting their work.” Total family welfare spending in Sweden is over 3% of GDP, much higher than in countries like Japan, South Korea and Singapore.

But restoring population growth in a society which has fallen into negative growth is extremely difficult. Countries like Japan and South Korea have undertaken long-term approaches to restore population levels with little to no positive outcomes. Japan, a country whose policies the Chinese government has already emulated, managed to temporarily boost fertility between 2005 and 2015, from 1.26 to 1.45, but by 2022 it had returned to the 2005 level.

“Belatedly, Chinese authorities have rushed to launch a series of policies, largely paralleling Japan’s demographic policy response to boost fertility, such as reducing school fees and providing convenient childcare, childbirth subsidies and housing benefits to young couples,” says Fuxian Yi. “But Japan’s approach has proved expensive and inefficient and China, which is “getting old before it gets rich,” does not even have the financial resources to fully follow Japan’s path.”

Some businesses are also trying to play a role in encouraging childbirth. Trip.com Group whose CEO James Liang is noted as a demographics expert has announced a scheme worth around ¥1 billion that would pay an employee ¥50,000 over five years for each new child they have. But such a payment is unlikely to make a real dent in the cost of raising a child.

A new way

It is highly likely, given the long lead time for any solutions to restore population growth, that China will have to choose the option of trying to innovate its way back to economic expansion through the increase of average worker productivity. The country has a history, particularly over the past two decades, of spending big on R&D and becoming highly innovative once it has acquired basic levels of knowledge from elsewhere.

There are now high levels of digitalization across all aspects of the country, including business and industry, and this appears to be one viable option for increasing productivity without increasing population. Another option would be a quicker shift towards a service-based economy, which could also be facilitated by the digitalization of manufacturing and the adoption of AI, but would face the same difficulties of human replacement rather than job creation.

“If you are able to educate people and equip them with the ability to utilize high-end technologies, then the number of people shouldn’t matter so much when it comes to the economy,” says Dr. Xiaobing Wang, Associate Professor in the Economics of China at Manchester Universtiy. “So if China can successfully upgrade its economy through animating the upper end of manufacturing and provide a more passive income, population shouldn’t be as much of an issue in relation to productivity.”

There are many benefits from the new wave of AI tools available both in the B2C and B2B spaces. These include lowering costs, lowering labor requirements, increasing efficiency and reducing errors, all of which in effect raise productivity. But there is one major barrier that seems to trump any of the benefits.

“Simply put, artificial intelligence and robots do not consume, and consumption is the major driver of any economy,” says Fuxian Yi.

One solution often proposed is the introduction of a scheme along the lines of universal basic income, to act as a catalyst for consumption as well as a boost to fertility rates, but the cost, especially for a country with a slowing economy and such a large population may well be prohibitive.

Growing up

China’s demographic issues are wide-ranging, complex and unique given the size of the country’s economy, its level of growth and population size. Most efforts to reverse population decline around the world have centered on a combination of financial benefits to families and lower parenting costs. China has already started doing both.

“Many people are worrying about the demographic shifts but in the short- to medium-term I’m not that worried because it’s a long-term issue,” says Wang, “The worry is that in the future, there will be too few young people and the labor supply will be low. But China is moving towards a high-tech economy and if successful, labor should not be a problem.”

But the current issue for China seems to be stimulating consumer demand. Without this, alternative solutions to population growth, such as AI adoption will be unlikely to stimulate productivity enough to offset the issues currently caused by shrinking demand.

“The problem will be if China fails to upgrade its economy from a high labor-intensive growth model, to a high-tech and consumer-driven model,” says Wang. “If that happens, the demographic issues the country currently faces will surely have a negative impact on the Chinese economy.”