When 2022 began, the government set a target of 5.5% GDP, a goal the market agreed was feasible. In fact, it wasn’t hard to find people who found this a conservative number. However, as Covid-19 continued, cities successively locked down to deal with rising cases, sometimes for months on end. Although this staved off the disease to some extent, it seriously affected economic growth, especially among small and medium-sized enterprises. Another factor in the slump is real estate. If estimates from the World Bank are to be believed, real estate, including up-and-downstream industries, accounts for as much as 30% of China’s GDP. With an industry this large and important to China, 2022’s property market turmoil has had a calamitous impact.

Under the influence of such major unfavorable factors, China’s GDP growth rate for the first three quarters of 2022 reached just 3%. Despite the relaxation of the zero Covid policy, business in most of the fourth quarter was conducted through restrictive epidemic prevention policies; the economy is therefore unlikely to perform well. It is estimated that the GDP growth rate in 2022 may still be around 3%.

At the tail end of 2022, everyone began guessing next year’s economic growth rate. A few representative ones include:

Wei Jianguo, Vice Chairman of the China International Economic Exchange Center and a former Vice Minister of Commerce: 8%.

Yao Yang, Dean of the China Center for Economic Research Peking University: China’s economy will grow by at least 6% next year. 8% would not be unreasonable.

Zhu Guangyao, former Vice Minister of Finance: 5 to 6%.

Liu Shijin, Deputy Director of the Economic Committee of the CPPCC National Committee: No less than 5%.

Overall, everyone is very optimistic about the Chinese economy in 2023. And they’ve got a point. First, the government has relaxed its strict Covid-19 prevention measures, giving the economy a chance to breathe. Second, the government has issued a series of measures to support industries that faced strict regulations in recent times: real estate, education and online platforms.

However, unfavorable factors remain. As for Covid-19, we used to think epidemic prevention hindered consumption, and that relaxing the tight measures would set of a wave of consumption and growth. We forgot that, at least in the short term, swathes of people would be off work sick, or self-CKGSB Case Center and Center for Economic Research 2 isolating in a more conscientious manner, shopping little, going out rarely. So, for now, Covid-19 is indeed still having a big economic impact.

At present, the most important planning event for next year’s development goals is the Central Economic Work Conference. According to Xinhua News Agency, the Central Economic Work Conference was held in Beijing on December 15-16. Xi Jinping attended and delivered an important speech. Li Keqiang, Li Qiang, Zhao Leji, Wang Huning, Han Zheng, Cai Qi, Ding Xuexiang and Li Xi all joined. This conference serves as a weathervane for the economic work of the coming year. From Xinhua’s report on this year’s conference, there are two points worth highlighting.

First, the steadfast commitment to the “two unwaverings.” This refers to the unswerving consolidation and development of the public sector, while encouraging, supporting, and guiding the development of the non-public sector, and ensuring that parties of all forms of ownership may equally use factors of production in accordance with the law, fairly participate in market competition, and equally receive legal protection. This correct and significant passage has been of great encouragement to the private economy.

In the 1950s, China implemented a “public-private partnership,” which eliminated private enterprises, and enabled its state-owned enterprises to dominate. Inbuilt problems in these stateowned enterprises meant that efficiency was low, and the economy hovered at a low level. In 1978, China took the major decision to reform and open up, allowing private enterprises to regain their space in the economy and develop step by step. It is worth noting that in history, the Soviet Union and Eastern European countries all carried out economic reforms, but each one failed. They all implement a planned economy. China’s reforms succeeded mainly due to the growth of China’s private economy. The reforms in the Soviet Union and Eastern countries were all limited to how to change specific operational methods in state companies, and the research was on how to improve operational efficiency in state-owned businesses. History has shown that this road is impassable, a dead end.

Regardless of why China decided to reform and face the world anew, the private economy was factored in from the start. Nian Guangjiu in Wuhu, Anhui is the typical example. He was a selfemployed seller of stir-fried melon seeds whose produce became popular. More and more people bought his melon seeds and Nian had to hire workers to help out, turning his enterprise into a veritable SME. The government’s attitude towards Nian was mixed. Some believed Nian Guangjiu was engaging in capitalism and advocated dismantling his endeavor. But in the end Nian Guangjiu was allowed to continue developing his small business.

It was around this time that China introduced foreign capital, in the form of foreign private enterprises. These companies not only brought in new capital, new technology and new management methods, but also new ideas, filling the gaps in Chinese people’s understanding of the private sector.

In the history of reform and opening up, the development space gained by private enterprises has changed constantly, but under the combined effect of a series of factors, they have turned into an important part of China’s economy. Now everyone knows that China’s reform and opening up has achieved great success. China’s economic aggregate has become the second largest in the world after the US, and hundreds of millions of people no longer live in abject poverty. For this to have happened, we give a nod to the development of the private sector.

Why does the central government repeatedly emphasize the “two unwaverings”? Because in reality there is no small difference in treatment between state-owned and private enterprises. To put it bluntly, discrimination abounds against private enterprises. One example is interest rates on loans. State-owned enterprises can get loans at a lower benchmark interest rate, while private enterprises tend to be offered rates that are a few percentage points higher.

The interest rate on loans to state-owned enterprises is significantly lower. This is not only a kind of discrimination of ownership form, but also a key determinant of soft budget constraints. These refer to when an actor makes a mistake and causes a loss, the ability to get help from other actors so that the full responsibility for its actions do not fall on its shoulders. For example, a state-owned enterprise may incur huge losses due to inefficiency. In general, market economy countries allow such a company to go bankrupt and become liquidated. In other words, this pays for the business’s operating mistakes. But in the case of state-owned companies, banks are willing to lend because the government backs the business, and the interest rate will be set in reference to government bonds.

For private enterprises, soft budget constraints are largely absent. When a company makes mistakes in its operations, bankruptcy and liquidation may be the only way. No one will pay for its mistakes. It faces hard budget constraints. Because of this, private enterprises must work harder and be more careful than state-owned enterprises. The impact on quality means private enterprises are leaner and more efficient than state-owned enterprises, as reflected in our corporate competitiveness index. However, funds flow from private to state-owned enterprises. This is obviously a mismatch of resources, which reduces efficiency and affects economic growth.

Second, many industries still have explicit or implicit restrictions on private enterprises. In 2006, Li Rongrong, then director of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, stated to the outside world that “the state-owned economy should maintain absolute control over important industries and key areas that are related to national security and the lifeline of the national economy, including military industry, power grid power, petroleum and petrochemicals, telecommunications, coal, civil aviation, Shipping and other seven major industries”. Although this statement does not completely exclude private enterprises from the seven major industries, it clearly expresses a kind of political discrimination.

In fact, what private companies need is not encouragement, but genuinely equal treatment. The reason is very simple. After 44 years of reform and opening up, private enterprises have proven essential to China’s economy. Having solved most of China’s employment issues, private companies are still not receiving the same kind of government support as the state sector. Private enterprises are more efficient while state-owned enterprises are less efficient, but the former get significantly fewer resources than the latter. This is not conducive to improving economic efficiency, nor is it conducive to achieving high-quality growth.

Second, more effort has to be made to attract and use foreign capital. The introduction of foreign capital has always been one of the basic tent pegs of the reform period, but now, the policy means different things. The Cold War lasted for decades, and the capitalist bloc led by the United States established the Bretton Woods system and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, in which trade and capital flows continued to grow. The Soviet bloc established another economic system. After decades of competition following little economic interaction, the capitalist bloc headed by the United States won out economically.

During this period, industries shifted from more developed economies with higher costs to countries with less developed economies and lower costs — first Japan and later the East Asian Tigers — in a process known as globalization. This has allowed poorer countries to integrate into the world economy, and most seized the opportunity have achieved sustained and rapid development. After China’s reform period began in 1978, it globalized fast and took over many industries transferred from developed economies. China’s import and export business began in earnest, and growth skyrocketed the country to economic-giant status.

As a winner in the process China should absolutely continue on the path to globalization. However, the world — particularly beyond China’s borders — has changed significantly in recent years. Let’s take the US and the chip industry. The United States imposes sanctions on China in light of its advantages in the chip industry. If the United States uses finance as a weapon to sanction Russia, it is now using high technology as a weapon to sanction China. There are more and more examples like this, and people are asking: will globalization continue? Zhang Zhongmou, the founder of TSMC, recently said that globalization is close to death, a view shared by many.

When things deteriorate internationally, China needs to maintain strategic focus and pick its battles. The most important thing has to be maintaining the overall development of globalization, because this is where China’s fundamental economic interests lie. Under such circumstances, the Central Economic Work Conference proposed attracting and using foreign capital more rigorously, a position we should encourage. When the US economy closes in, China is right to keep its economy as open as possible.

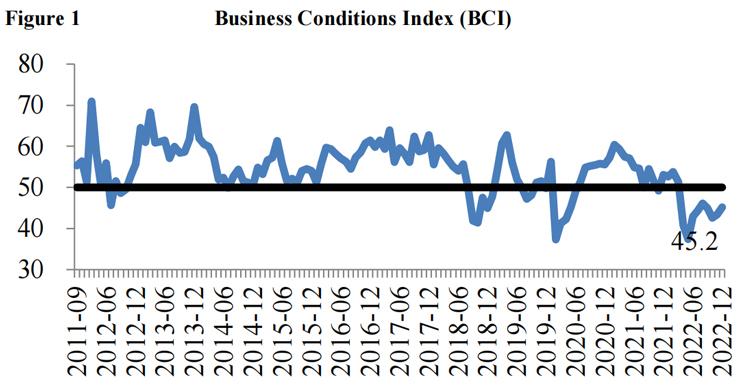

It has been 44 years since the reform period began. China has experienced countless setbacks and bright moments, but has recently fallen into a quagmire, as evidenced by our index. The CKGSB Business Conditions Index (BCI) for December 2022 is 45.2, compared to 43.4 last month (Figure 1). Albeit slightly up on last month, this is very weak. In recent months, the Chinese economy has been noticeably depressed.

What’s more, the BCI has hovered below the confidence threshold of 50.0 for months.

Source: CKGSB Case Center and Center for Economic Research

No matter what the growth target is for next year, the only way to get out of t6he current predicament is to deepen the reform and opening up process. Innovating through the current quagmire is key to shifting the economy in a positive direction, and also the only way to make a success of the current situation.

This is a commentary on the CKGSB BCI report for December 2022 to which you are welcome to refer for detailed statistics. Do not hesitate to contact the BCI team by email for the accompanying BCI data report.

CKGSB Professor Li Wei

26 December 2022