What does the future of Chinese state-owned aircraft manufacturer Comac and its top products look like?

Building a jet to rival those made by Boeing and Airbus will be a challenge for state-owned aircraft maker Comac

The recent fatal crashes of two Boeing 737 Max 8 jets have placed the commercial aviation sector under intense scrutiny. It was unusual for the same type of jet flown by different airlines—Lion Air in October 2018 and Ethiopian Air in March 2019—to experience a catastrophic failure within such a short time period.

The crashes, that together claimed 346 lives, harmed Boeing’s reputation and raised questions about its viability and possibly more importantly that of the commercial aviation duopoly it shares with the Franco-German joint venture Airbus. Currently, Boeing and Airbus account for 99% of global large plane orders and 90% of the overall commercial aviation market, according to aviation analytics firm, the Teal Group.

One alternative manufacturer for passenger jets is China’s state-owned aircraft manufacturer, Comac. Timothy Kuder, an aerospace analyst at consultancy Frost & Sullivan, believes that Comac will add needed extra supply to the burgeoning commercial aviation market. “The Boeing-Airbus duopoly is causing a backlog,” he says. “Airlines are waiting for six years to get a new airplane.”

For China, therein lies an opening. “The Chinese would be fools not to exploit the situation,” says Shukor Yusof, founder of Malaysia-based aviation consultancy Endau Analytics, speaking of the perfect storm created by the lack of capacity as well as the crashes. “They are trying to take advantage of it in any way they can, twisting the arms of their domestic airlines.”

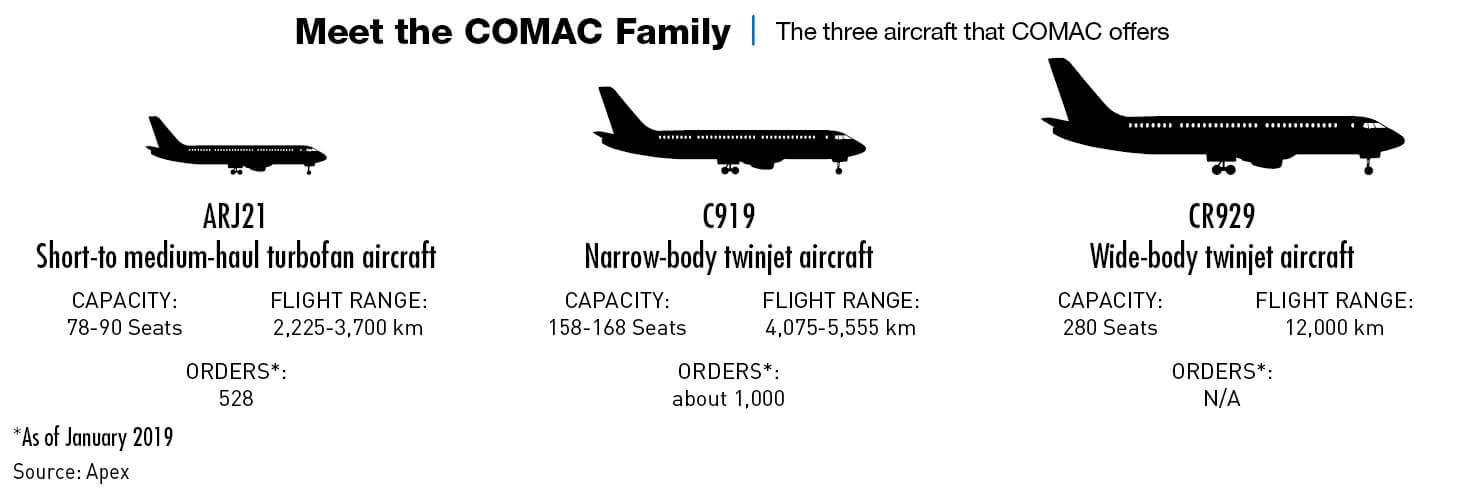

Comac, which was established in May 2008, is China’s bid to build a commercial aircraft base from the ground up. The state-owned company has three airplanes in its product range. The first is the regional jet ARJ21 (which entered service in 2016), and is the only one so far that has been flown by a commercial airline. Ten ARJ21s have been built and sold to state-owned Chengdu Airlines.

The second plane is still on the drawing board—the CRAIC CR929, a joint venture between Comac and the Russian United Aircraft Corporation expected to go into service in 2027.

The third plane, the narrow-body C919, is the one which has captured the attention of global aviation industry watchers. Carrying up to 168 passengers and with a flight range of 5,555km, it is targeting the same market as Boeing’s 737 Max and the Airbus A320. It is the first Chinese aircraft that would be able to compete with the Boeing-Airbus “large plane” duopoly.

The state-owned China Daily reported that as of February, Comac has received 815 orders for the C919, almost all from state-owned Chinese domestic airlines and aircraft leasing companies.

In terms of total sales, China is set to overtake the United States to become the world’s largest commercial aviation market by 2022. Comac itself reckons that 9,000 passenger aircraft with a total value of $1.3 trillion will be delivered to the Chinese aviation market over the next 20 years, and Beijing is intent on building a commercial aviation industry which can capture a substantial slice of that business, as well as challenge Boeing and Airbus in other markets.

At the same time, aviation is integral to China’s industrial transformation blueprint. To join the ranks of the rich countries, Beijing must become a world-class manufacturing power on par with that of the Europe, Japan and the US. Being able to deliver a viable commercial airliner would help buoy Beijing’s advanced manufacturing dream.

Learning to fly

The Chinese government founded Comac in the era when, in the words of the late leader Deng Xiaoping, China was still “hiding its capacities and biding its time.” The world’s eyes were set on China primarily because of its widely hailed “reform and opening up,” culminating in the 2008 Beijing Olympics. China’s state-dominated industrial policy had yet to capture much attention beyond a small circle of analysts and China watchers.

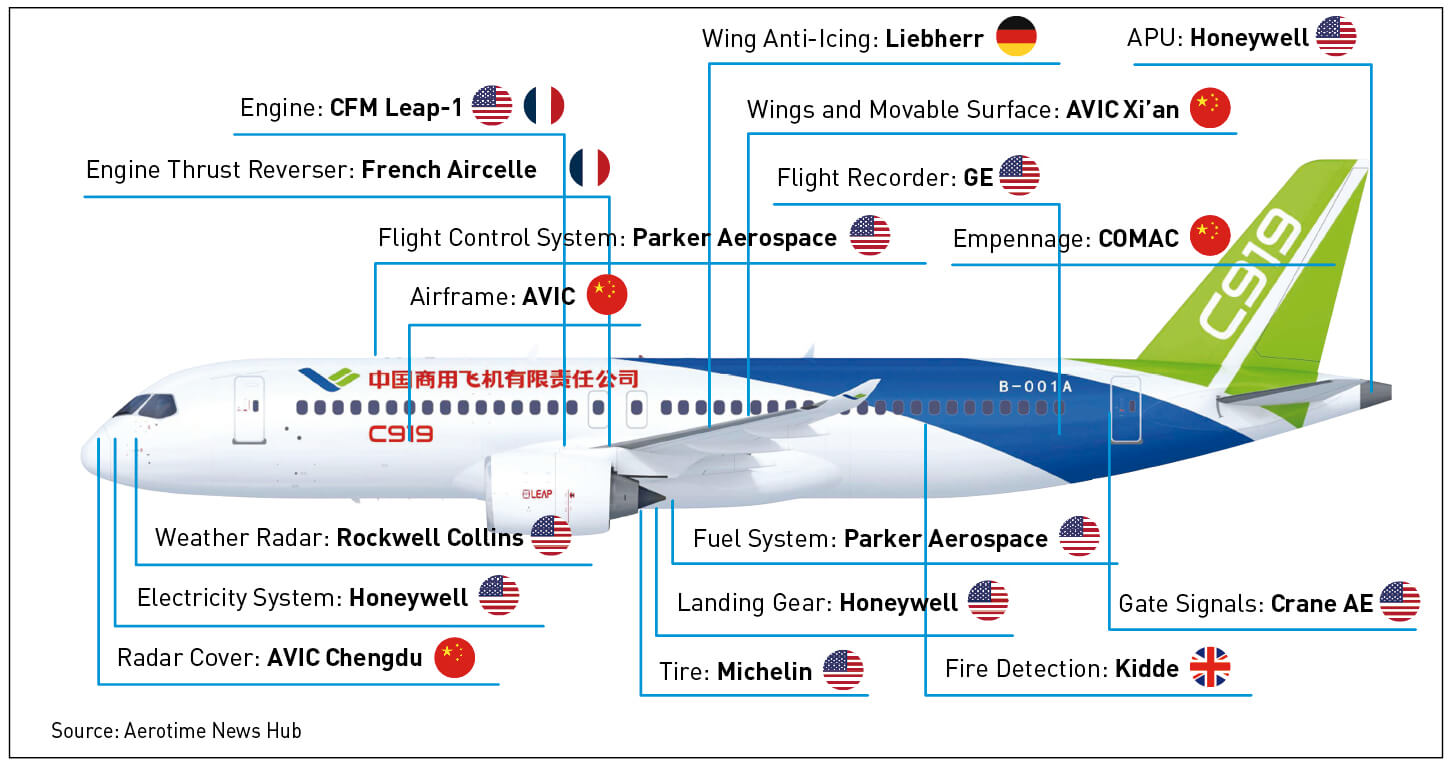

From the outset, Beijing has been working to create an aircraft industry independent of foreign technology. But for now, foreign firms still play a crucial role. GE Aviation and its partner AVIC Systems provide IT systems, cockpit displays and black boxes for the C919. Hamilton Sundstrand makes the power supply system for the aircraft, Rockwell Collins supplies navigation and control systems and Honeywell produces the brake control system and tires.

Boeing’s travails with the 737 Max offer an opening for the C919, and for other aircraft configurations in the future. The C919 “is a perfect example of Chinese intentions [to challenge Boeing] and should send fear into the hearts of Americans,” said financial analyst Bruce Wilds in a Seeking Alpha commentary published after Boeing grounded the 737 Max in March. “It would be incredibly naive to underestimate China’s resolve in rapidly becoming a player in a field that will move it up the manufacturing food chain.”

To be sure, the C919 is a more economical alternative to the Boeing or Airbus equivalents. China National Radio has forecast that a C919 will sell for $50 million, compared to $100 million or more for the Boeing 737 Max, depending upon configurations. For developing countries in which Beijing is already building airports as part of its Belt and Road infrastructure plans, buying Comac jets “is very tempting,” says Yusof. Backed by state cash, Comac could offer the jets to these countries for a low price.

Top state-owned carriers such as Air China, China Eastern Airlines and China Southern Airlines will certainly be the biggest buyers of the C919, and it is unlikely they will have much choice in the matter: The Chinese government expects them, as state airlines, to support the national commercial aviation initiative.

With that in mind, Liu Shaoyong, chairman of China Eastern Airlines, formally submitted a proposal in March to encourage Chinese airlines to procure domestically-made jets.

Encountering turbulence

Other analysts are less sanguine about Comac’s prospects. They point to commercial aviation’s high barrier to entry, the brittleness of the company’s state-led business model and its mixed track record to date.

“Programs mandated by a government five-year plan seldom produce competitive jets,” says Richard Aboulafia, vice president of analysis at the Teal Group.

Delays are also common, with the Comac ARJ21 being a prime example. The plane first flew in 2008 but was then subjected to numerous setbacks and was not certified even for flights in China until 2014. It was another two years before it was introduced into service, over a decade behind its original schedule.

Delays have plagued the C919 as well, which is now set to enter operation in 2021, six years behind schedule. It has been 13 years since the C919 project began.

The delays aren’t surprising, given the challenges of aircraft production. “Building a jet is a complex job—it takes time,” says Frost & Sullivan’s Kuder. “Many different suppliers have to coordinate with each other.”

Beijing’s unattractive conditions for suppliers—mandatory vertical integration and China local production requirements—could end up costing Comac dearly, Aboulafia says, because Comac’s suppliers are not naive.

“Suppliers are going to show up with stuff from decades ago and say it’s the latest technology,” he says. “Even if just 20% of them hold back [on cutting-edge technology], there’s an inferior jet.”

That was arguably the case with the ARJ21, which Aboulafia describes in unflattering terms. The design resembles McDonnell Douglas’s DC-9 produced between 1965 and 1982, and “is a classic example of re-inventing the wheel. The engines and avionics are pretty much identical to any other regional jet designed 20 years ago,” he says. He adds that the dominant alternative regional jet maker, Brazil’s Embraer, is now phasing out the same General Electric CF34 engine that Comac is just introducing.

While Beijing can ensure state-owned carriers place orders for Comac jets, non-Chinese airlines are all heavily invested in Boeing or Airbus infrastructure. “No airline is going to take a few Comac aircraft with all the resultant training and introduction costs just to bridge a gap in Boeing capacity,” says John Grant, director of UK-based JG Aviation Consultants.

Aboulafia also has doubts about the C919’s viability. He says that there is a serious risk that by the time the C919 enters service, “Airbus and Boeing will be offering products that make this jet look obsolete. The [current] A320Neo and 737 Max look pretty good against it, even without any kind of product improvement packages.”

Long way to the top

But in the long term, Comac has huge potential because of China’s aviation market fundamentals. The market is huge and growing steadily, and government support is robust.

The main problem for Comac is that its business model is not market oriented. “Vertical integration is a very bad idea,” says Aboulafia. “Jet makers need to be free to select ‘best-in-class’ content for [components built into] their jet from a wide range of suppliers with no permanent links to any specific companies.”

Grant of AG Aviation Consultants expects that Comac will do good business in China and also perhaps across Africa, where the aircraft could be included as part of wider trade agreements. But it is unlikely Comac would be able to break into the European or US markets in the next two decades, he says.

Indeed, Comac is not yet certified by the US’s Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) or the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Those two certifications are “the gold benchmark for flying anywhere in the world,” says Endau Analytics’ Yusof. Without them, aircraft are restricted from flying to much of the developed world. Comac planes are currently certified only to fly in China and in parts of Africa, Asia and South America that recognize Chinese certification.

In October 2018, business aviation publication Aviation International News reported that Comac had begun re-evaluating the C919’s flight-deck design to satisfy FAA requirements.

Comac vice president Wu Guanghui said in March that the company had applied for approval from the EASA, aiming to be green-lighted in three to four years, and the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) and the EASA signed two framework agreements in May covering airspace security and flight patterns, which would support the C919’s entry into the European market.

But to compete with Boeing and Airbus, Comac still has a long way to go. The world’s two foremost aircraft makers “have a global footprint of customers and a very comprehensive range of aircraft with all the major airlines using their aircraft and with order books that extend into the next decade. Comac has nothing like that scale and depth of customer,” Grant says.

However, Comac would not appear to face big headwinds as a result of its “Made in China” label because of the close involvement of world-class suppliers in the project and China’s strong aviation safety record of recent years. China has not had a deadly crash since 2010, a major improvement over the 1990s when seven crashes between 1992-1994 claimed 492 lives.

Many frequent flyers said they would be willing to give Comac a try, with some more enthusiastic than others. “With some inherent biases, I might feel a bit uneasy, but it wouldn’t ultimately prevent me from flying in a Chinese-made plane,” says Jun Wakabayashi, a Taipei-based analyst for the AppWorks accelerator.

But given the damage that Boeing’s reputation has incurred from the 737 Max’s troubles, Comac will need to pay extra attention to safety, says Frost & Sullivan’s Kuder.

“They [Comac] really have to nail the safety,” he says. “If they were to have an instance like the 737 did in the next five to 10 years, I don’t think they would recover from it.”