Rivals race ahead of Apple in China’s smartphone and tablet markets. What does it mean for Apple’s future?

Li Tingting unwraps a new iPhone 5S outside the Apple store in Sanlitun, a glitzy shopping district in Beijing. She’s had her eyes on an iPhone for some time, she says, and after a few months finally saved up enough money to buy one. Li bought the iPhone because it looks good and is easy to use. But she is an exception. “Almost all” her friends own a smartphone made by Samsung, HTC, Huawei, or another non-Apple brand, she says.

These smartphones and tablet computers based on Google’s Android (and to a much lesser extent, Windows) operating software have made impressive gains over the past couple years. Their generally lower prices and wide carrier reach have pushed Apple down to fifth place in China’s smartphone market as of the third quarter of 2013, according to Canalys, a research firm. While the company still retains a lead among tablets, its share of the market almost halved over the past year. Combined with tepid demand for its new mid-range smartphone, the iPhone 5C, some tech pundits are wondering if Apple has lost its mojo in China.

Not necessarily, say some analysts. True, Apple faces growing competition in China. But it is playing a very different game than many of its rivals—and a much more profitable game at that. For now, the company seems content to preserve its high margins and lure customers into its content ecosystem, even if that means losing its market dominance.

“It all comes back to the question: what is it worth to gain market share if they have to sacrifice billions of dollars of profitability?” asks Wayne Lam, a senior analyst at the research firm IHS. “Because that’s the calculus they’re doing at Apple.”

Siri, Interrupted

The Cupertino-based company’s travails are hardly confined to China. While iPhone sales are up, Apple’s share of the smartphone market fell to 14% from 19% between the third quarter of 2013 and a year earlier, according to Gartner, a research firm. By contrast, the share of Android-based smartphones rose to 79% from 64%. Similar slides have occurred in the tablet computer market, and the entire notebook market appears to be in a structural decline.

Falling market share, along with a dearth of new product lines since the iPad was released in 2010, has triggered feverish speculation among tech types about whether Apple, who didnʼt respond to a request for comment, has lost its edge. At the very least, it has put pressure on the company to look for new sources of growth, especially outside of the saturated US and European markets.

“China is important to Apple because it is the last untapped market out there,” says Lam of IHS. In 2011 some 118 million smartphones were shipped in China, about the same as the US. This year that figure should be about three times higher, at 360 million, according to IDC. China’s tablet computer shipments have been growing at only a slightly slower pace, making the country the world’s second-biggest tablet market behind the US.

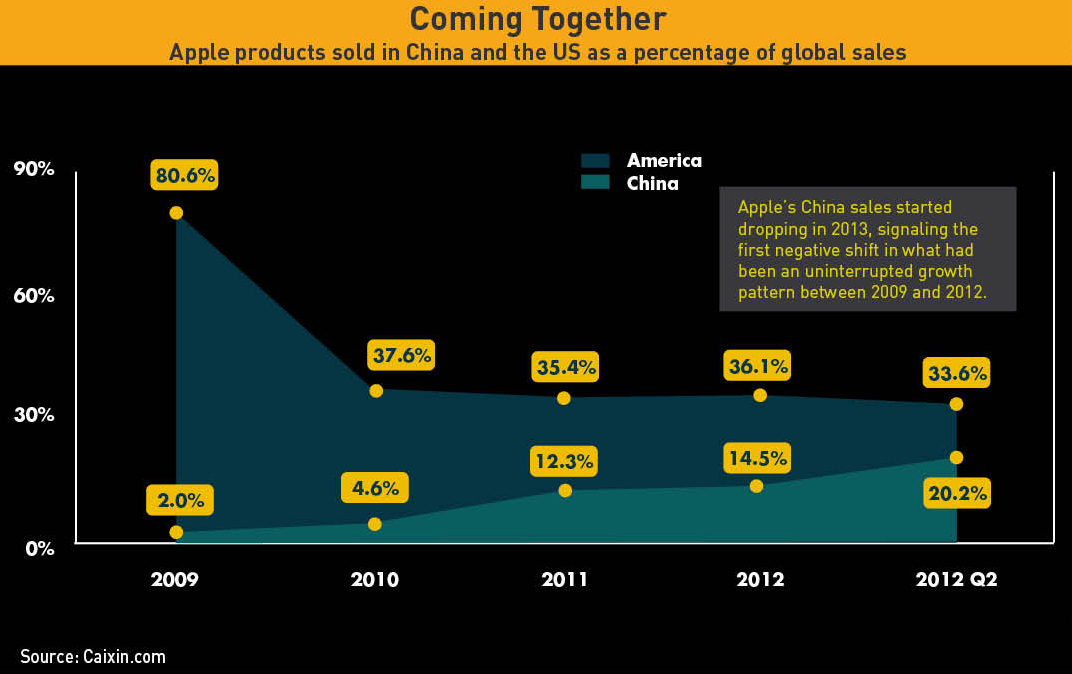

The rising tide of tech in China has been lifting all ships, including Apple. iPhone sales in the country increased by 32% in the third quarter of this year from a year earlier, according to Canalys. Estimates by IDC suggest iPad sales rose by 28% year-on-year in the second quarter. Overall, Apple notched up $5.73 billion in revenues in the Greater China region for the latest financial quarter ending in September. That’s a 6% year-on-year rise, compared to just 1% growth in the US and zero growth in Europe. China currently ranks as Apple’s second-biggest market, accounting for over 15% of global sales (a slightly higher proportion than the year before). The company’s CEO, Tim Cook, has said he expects China to become its largest market in future.

But like elsewhere, the company’s market share in China is slumping. iPhones accounted for just 6% of smartphones sold in the country during the third quarter, down from 8% last year, according to Canalys. It retains a lead among tablet computers, but analysts at IDC reckon the company’s market share was 28% in the second quarter, down from about half a year before.

In its place, devices based on Android operating software have thrived and now account for about 80% of the smartphone market alone. Among global brands, Samsung has enjoyed strong growth; the company’s 21% market share makes it China’s largest smartphone device maker. Analysts say Samsung’s position can be largely chalked up to a combination of both wide carrier availability and its presence at both the middle and high ends of the market (most companies concentrate on only one). But it is local Chinese companies—such as Lenovo, Yulong (maker of Coolpad phones), ZTE, Huawei and Xiaomi in the smartphone business, and Acer and Asusteck in the tablet market—that have enjoyed huge gains and media attention.

Local players have some clear advantages. They are unencumbered by the import taxes that have effectively shut foreign manufacturers out of the low end of the market. They are also generally more responsive to the needs of Chinese consumers, says Teng Bingsheng, Associate Professor of Strategic Management at CKGSB. Perhaps the best example is Xiaomi, a Chinese smartphone company with a near-obsessive focus on consumer feedback that provides weekly software updates based on user requests. The firm’s boss, Lei Jun, has been feted as “China’s Steve Jobs”. In the second quarter, Xiaomi, then less than three years old, briefly overtook Apple in terms of market share.

‘Gateway Drugs’

But these gains do not necessarily come at Apple’s expense. For starters, the company has a fundamentally different business strategy than its rivals. “Apple is unique in that they’re not just trying to sell a piece of hardware,” says Ben Bajarin, San Jose-based Director of Consumer Technology at the research firm Creative Strategies.

He notes that Android-based smartphone companies generally make money by selling consumers hardware (the device), and then waiting for them to buy another in a year or two. Aside from price and a few features, there is little to set hardware competitors apart. This “commoditization” of the market means profit margins are thin to non-existent, especially at the low end. The same dynamic applies to the tablet computer market, in which dozens of companies crank out ultra low-cost tablets but few actually turn a profit.

By contrast, Apple views its smartphones and tablets as stepping-stones for consumers to enter its “ecosystem” of online content. Not only does the iTunes store provide a good source of revenue—it makes about twice as much money as Google’s app store—but Apple also believes it makes the brand “sticky”, says Bajarin. Once consumers invest in Apple’s music, movies, apps and so forth, they’ll for their next phone or tablet. For China in particular, it helps that Apple has been generally more successful at directly distributing its global content (such as apps, movies, and music) in the country, he adds. The upshot is that while Apple may control only a fraction of the global market, it raked in a whopping 69% of all smartphone profits in 2012, according to data from Canaccord. Its nearest rival, Samsung, took in less than half that figure. Together the two accounted for over 100% of industry profits because all other companies, on average, lost money. The situation is similar in the tablet market, where Apple’s profit on each iPad sold is reckoned to be multiples higher than its competitors.

Furthermore, Apple and other device makers mostly compete for different consumers in China. The explosive growth of Chinese tech companies can be largely chalked up to a surge among Chinese consumers entering the low- and middle-end of the smartphone and tablet markets. Apple is decidedly uninterested in such users. “Apple’s market strategy within China has always been more akin to a luxury brand than a consumer electronics company,” says Lam of IHS. In both absolute terms and relative to local incomes, the iPhone and iPad are much more expensive in China than in the US or Europe. The company’s cachet and cutting-edge innovation help it sell at prices well above what Lam calls the “magic marker” of RMB 3,000-3,500. Moving down-market would not only squeeze Apple’s margins, it might also threaten its high-end status.

Many thought the company would make an exception earlier this year, when rumors swirled that Apple was preparing to launch a lower-range product to gain back market share, especially in China. That product, the iPhone 5C, went on sale in September alongside the more advanced iPhone 5S. The 5C is unusual: it is cased in plastic (not the traditional metal) and offered in a wide variety of colors. But at RMB 4,488 ($737), it is only a bit cheaper than the RMB 5,288 ($868) of the flagship iPhone 5S.

“It’s very obvious that they don’t want to go for a low-cost strategy,” says Nicole Peng, Research Director for China at Canalys. “They don’t want to compromise their brand.” Instead, Apple is using the 5C to appeal to a younger crowd such as those in their teens and early 20s, she says.

The new iPhone line-up also contained a little-noticed technical change: both the 5C and the 5S are compatible with TDLTE, a 4G technology unique to China Mobile, the country’s biggest carrier. Apple had resisted signing a deal with China Mobile because the latter’s weird 3G and 4G technologies are incompatible with the standard formats found in most other countries. But the latest tweak paves the way for a tie-up that is all but official.

There’s no question a deal would give Apple a shot in the arm. China Mobile has almost 750 million phone users, and plenty will want to switch to an iPhone. Moreover, China Mobile could help Apple extend its reach into third- and fourth-tier Chinese cities, says James Yan, a Shanghai-based analyst at IDC. In all, he estimates a deal would probably goose iPhone sales by 10-20%.

Apple’s Red Queen

That may bode well for Apple’s future in China, but the country presents some unique landmines as well. In March the state broadcaster launched a series of scathing reports on the company’s warrantee policies in China, prompting speculation about whether the government was trying to shake Apple’s position in China. The fiasco ultimately led to a public apology by Tim Cook.

The reports probably did weaken Apple’s reputation among Chinese in general, but brand damage among the company’s more cosmopolitan (and independent minded) consumer base was minimal, says Teng of CKGSB. Moreover, the attacks seemed too opportunistic to be part of a concerted effort to weaken Apple and boost its Chinese competitors. “I don’t think state media has [an industrial] agenda,” he says. “They just need to get their ratings up.”

Teng argues that the biggest challenge for Apple in China will be maintaining its position as an innovation leader. Some degree of falling market share is inevitable as Chinese consumers snap up cheaper phones. But if Apple cannot continue churning out cutting-edge technology and new products it will lose its grip on high-end consumers. That would force the company to slash margins and move down-market to stay competitive.

“It only takes a couple design cycles for them to be disrupted by another upstart,” says Lam of IHS. “So the overall thought process at Cupertino is: how can we keep this up? They’re trying to innovate as fast as they can and keep that market leadership, because they know once the jig is up–once you step across that line and start going down-market–it’s a race to the bottom.”