A new energy cycle

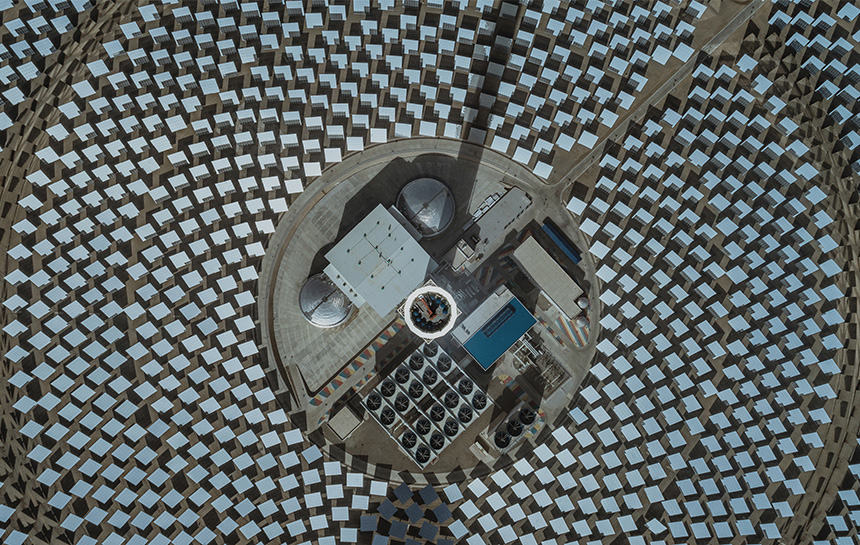

It seems fitting that a desert named after the Mongolian word for sky is where China is building one of its biggest-ever solar energy projects. The expansion of the photovoltaic (PV) power base in the Tengger Desert, straddling the Chinese regions of Inner Mongolia and Ningxia, will have three gigawatts of generation capacity once finished, making it one of the largest globally and big enough to power nearly three million Chinese homes annually.

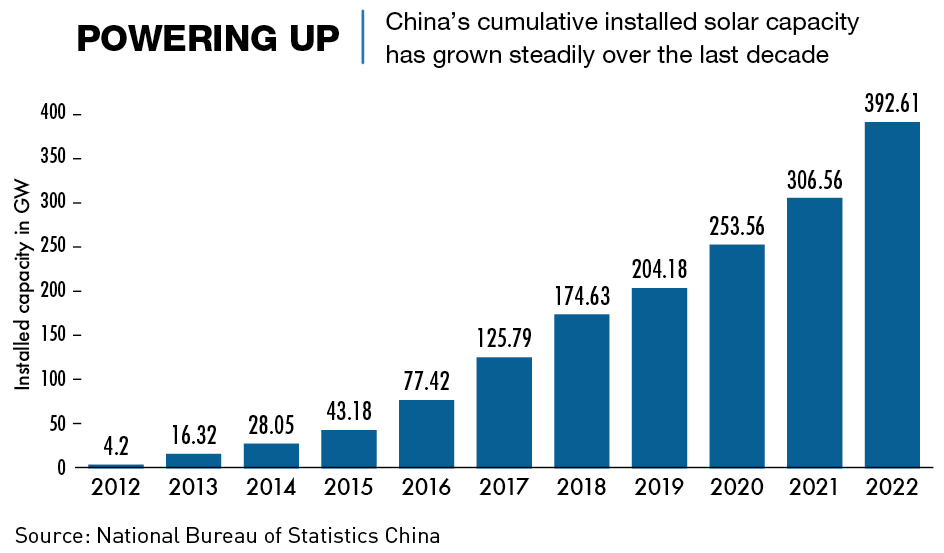

In 2010, China had only 1 GW of solar power capacity, but ended 2021 with 306.56 GW, and added a further 87 GW in 2022, which is not far off the total existing solar capacity in the US today.

“At the very beginning, China’s solar industry had no domestic raw materials, no domestic market and no domestic equipment,” says Jin Boyang, a senior energy transition analyst at financial company Refinitiv. “Now China is the top manufacturer, has the most installed capacity and generates the most PV electricity. The achievement is truly impressive.”

How it’s made

The booming solar photovoltaic (PV) industry is broadly comprised of three segments. The making of a solar panel starts with the raw material polysilicon, an ultra-refined crystalline form of silicon that is cast into ingots and then sliced into thin wafers. Tongwei Solar—interestingly also a leading fish feed maker—and New York-listed Daqo New Energy are two of China’s, and the world’s, largest polysilicon producers.

Once finished, midstream giants like LONGi Green Energy Technology—the world’s biggest producer of solar panels—wire up the wafers into cells which convert electrons excited by photons of light into electricity. These are then used in the final stage—the construction and operation of solar power plants, such as the one in the Tengger Desert.

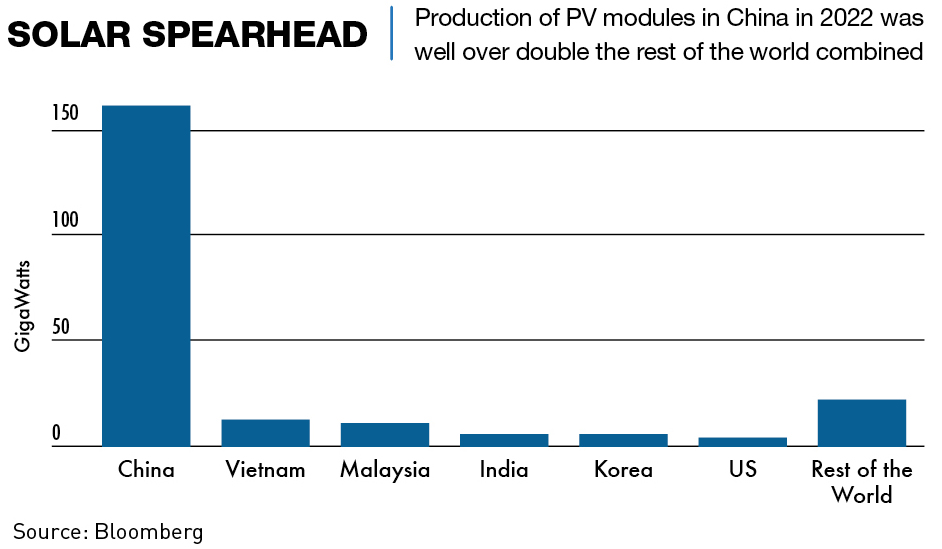

Today, the solar-powered future is being assembled in China. The country’s share of all three manufacturing stages of solar panels—from polysilicon, ingots and wafers, to cells and modules—exceeds 80%, and the country is also home to the world’s 10 top suppliers of solar PV manufacturing equipment.

But the domestic PV market suffered from a lack of profitability during its early years. Adoption was held back by high prices, a lack of government support and challenges with installing solar panels, leading to 90% of aspiring PV companies closing due to overcapacity, weak demand and uncompetitive production.

“Hundreds of Chinese companies attempted to get into making polysilicon between 2006 and 2012,” says Jenny Chase, head solar analyst at energy research firm BloombergNEF. “The vast majority failed and went bankrupt, but a few like Tongwei and Daqo succeeded in making adequate-quality polysilicon.”

China’s solar system

China’s energy footprint this millennium has been defined by two ongoing developments, the sharp rise and now slow-motion decline of coal and the small-but-growing use of renewables.

Coal still supplies more than 51% of primary energy demand, and despite dropping from around 75% in the early 1990s, absolute consumption has nearly quadrupled since then, reaching a historic high last year. On the other hand, the country is now a clean energy superpower, accounting for 44% of new wind and solar added globally in 2021. Solar now makes up 4% of China’s total energy supply, up from 0.6% in 2012.

In 2022, solar started to outshine wind in leading China’s energy transition, with cumulative installed solar capacity reaching the number one spot for the first time in August. Starting from a total of 306.56 GW of capacity, China added 58.24 GW of solar capacity in the first 10 months of 2022—overtaking the previous year’s total of 54.93 GW with two months to go despite rising material and panel costs.

China generated more electricity from solar PV last year than the US, Japan and India, the next three largest producers, combined. But the country leads not only in power generation, but also in technological innovation.

“As the leading solar manufacturing country, China is at the center of innovation in solar manufacturing as measured by patents, not just by number but their importance in the field,” says Anders Hove, a senior research fellow at the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies. Chinese companies and organizations, led by State Grid Corporation of China, make up four out of the top five solar patent holders, with Samsung the sole outlier.

PV technology has been around since the 1950s but Chinese researchers are continuing to push the envelope. In November 2022, LONGi broke a five-year-old record for power generated by a silicon cell, with a cutting-edge heterojunction (HJT) design converting 26.81% of sunlight into electricity—the first time a Chinese company has occupied the top spot.

While LONGi’s new record is approaching the 32.33% ceiling for the maximum possible efficiency of silicon cells, China is already developing cells using a next-generation solar panel material called perovskite that could mean lower costs and even higher efficiency. Chinese companies held 68% of all perovskite battery patents in October 2022.

“China is at the forefront, they definitely rank among the top countries in terms of technology,” says Frank Haugwitz, a senior advisor at German clean tech consultancy Apricum, with two decades of experience in China’s solar sector. “But what is really interesting is there are now innovation platforms where dozens of Chinese companies contribute expertise—instead of competing all alone, they all compete together in pursuit of technological advancements.”

Global solar PV manufacturing capacity has migrated from Europe, Japan and the US to China over the last decade, with Beijing investing more than $50 billion in new PV supply capacity—ten times more than Europe—and the creation of more than 300,000 manufacturing jobs across the solar PV value chain since 2011.

Today’s leadership in solar energy generation means these homegrown giants are supporting buildout in the rest of the world, bringing down costs worldwide, benefitting a world confronting climate change. Chinese solar product exports more than doubled year-on-year to $25.9 billion in H1 2022, not far off the $28.4 billion exported for all of 2021.

Sunshine policy

The Chinese government has supported the solar industry for decades through low-interest loans, cheap land and energy, tax rebates and other subsidies, to build the world’s most integrated and efficient solar PV supply chain—although other countries offered generous financial support too. Central policymakers were hands-on from the beginning, first with the ‘Brightness Program’ in the early 2000s to electrify rural communities via solar and wind power installations, and then began to offer lines of credit to manufacturers in 2006-2012, although many of them were never drawn down.

“China was quick to recognize the solar industry as a strategic industry, something to invest in for the long run,” says Haugwitz. “You could execute projects at a faster pace because it was given priority. The time to get all the paperwork done for setting up a solar factory was shortened to as little as possible—as it is for any prioritized industry in China.”

“The consistency of support helped Chinese companies build scale and co-locate manufacturing plants for cells and modules with those for glass, encapsulant and other key materials. China’s scale and commitment has been a major factor in bringing down the price of solar modules from $4.20 per watt in 2008 to $0.25/w today,” says BloombergNEF’s Chase.

The inclusion of clean energy goals in China’s recent five-year plans (FYPs) has underlined Beijing’s political support for renewables, encouraging commitment from investors and local bureaucrats. Specific FYPs for solar helped ensure industry development stayed on track and set targets for capacity installation, many of which were reached several years early.

Government support has remained robust even as China’s solar sector has matured into a world-class industry. For instance, in September 2021 the national energy regulator kicked off a ‘whole-county’ program to boost rooftop solar by aggregating small projects into larger batches, luring bigger developers. Some 676 counties and cities are taking part and could eventually add another 600 GW of capacity. “This kind of intervention is very unlikely in the West, but it will certainly become a major incentive for the industry in China,” says Jin from Refinitiv.

Other countries have looked to emulate Beijing’s stellar policy support. BloombergNEF’s Chase notes that India—another fast-growing solar market—has supported its manufacturers since 2013 and now boasts several brands with international recognition such as Waaree Group and Vikram Solar.

The US is also working to catch up to China’s enormous spending on clean energy, a new front in the geopolitical competition between Washington and Beijing, introducing regulation that is forecast to result in 69% more solar deployment over the next decade.

Still, China leads the world in its commitment to solar. “The level of support is peerless internationally,” says Jin. “It’s unimaginable that the US or Europe would be willing to push forward policies such as new energy hubs or the whole-county solar program because they may not be economically feasible.”

Growing pains

As China races toward a solar-powered future, new challenges, such as solving the intermittency of supply from renewables, need to be overcome. Pairing solar energy systems with high-quality battery storage is seen as the most viable solution, but the domestic battery storage sector is underdeveloped. Battery storage projects in China currently have the lowest utilization rate of any major generation source, and, thanks to high lithium battery prices, cost more than coal power plants, pumped hydro storage and other storage options.

China’s massive solar installation volumes mean waste disposal and end-of-life management are a looming issue, with the weight of retired panels predicted to reach up to 1.5 million tons by 2030. Recycling is now getting national attention, with the 14th FYP for developing a circular economy including the recycling of solar panels among its key priority projects.

“The average life span of a solar panel is now as long as 25 or even 30 years,” says Haugwitz. “But China does not want to wait until it has so many panels that it doesn’t know how to properly dispose of them, and so the national government is looking into how solar panels will be properly recycled in the long run.”

Then there are structural problems related to the design of wholesale electricity markets in China that have restrained renewables adoption. Hove explains that China’s power market, the biggest in the world, still relies on monthly and annual electricity contracts for generators, which are dictated by the central government and a poor fit for variable solar. Spot markets, where products are bought in real time, are more suitable but still in their infancy in China, where they account for a fraction of electricity sales, according to Hove. This contrasts with Europe and the US, where spot market price signals help integrate variable renewable energies into the power system.

While China’s solar industry currently casts a shadow over all others, the sector has gone through boom-and-bust cycles before. Ten years ago China’s first solar boom fizzled as a string of major players—including Suntech Power, once the world’s biggest panel maker and at one time worth $16 billion—went bust. The market at the time was heavily export-driven, and outside demand dwindled following the 2008 financial crisis, an issue compounded by the anti-dumping investigations conducted by the US and Germany, among others.

China’s tight grip on the solar supply chain has also come under greater international scrutiny after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 flagged the risks of relying on a single provider for anything. Solar manufacturing is concentrated in China, and 2022 saw a two-month lockdown in Shanghai, a factory fire in Xinjiang and a drought-induced power crisis in the southwestern province of Sichuan all interrupt exports of polysilicon.

But for other countries, localizing the production of solar PV technology won’t be easy or cheap. The US would need to invest $25.1 billion upfront to onshore enough manufacturing of a solar panel’s key components to meet its PV demand by 2030. The cost would be $44.1 billion for Europe, and both bills would not include operating costs, such as energy, labor and materials, which are generally more important than upfront investment.

Lighting the way

While PV technology is largely mature, innovations are still ongoing in the crystalline silicon cells that dominate the industry. A shift to more efficient monocrystalline wafers accelerated last year, while a more efficient solar cell design known as “passivated emitter rear contact” expanded its dominance to nearly three-quarters of the market.

Even higher efficiency “n-type cell” technologies—such as modules produced with tunnel oxide passivated contacts (TOPcon) cells and panels based on cells with a HJT design—expanded commercial production last year to capture one-fifth of the market. As TOPcon and HJT become mainstream, China is poised to reap the benefits as 220 GW and 150 GW of new production capacity is currently planned for TOPcon and HJT respectively.

The gains are mostly marginal, according to Haugwitz. “There is no older or newer technology. It’s all based on silicon so the raw material hasn’t changed—just the composition of the materials used in order to harvest more of the sunlight and convert it into power.”

With China adding a record 87 GW of new solar capacity in 2022, the sky is the limit for PV’s contribution in the world’s biggest energy market. To achieve Beijing’s pledge of carbon neutrality by 2060, an average of 200.8 GW will be built every year through 2060, dwarfing the 37.6 GW installed annually in 2015-2020. At that rate, solar is projected to overtake coal as the country’s primary energy source by around 2045.

China’s grandest solar ambitions may even take it off-world. LONGi said in September 2022 that it would send panels into space as the first step in plans to test the feasibility of harnessing the sun’s power in orbit and transmitting it back to Earth. The announcement came three months after Chinese researchers at Xidian University in Shaanxi province successfully tested a full-system model of a power station that captured sunlight 55 meters above the ground, converted it into microwave radiation, beamed it through the air to a receiver station on the ground, where it was then converted into electricity.

But Haugwitz is skeptical that space-based solar power will lift off soon, if at all. “It’s a question of who can afford it. I don’t see commercial implementation happening in our lifetime,” he says.

More down-to-earth applications for solar energy have plenty of potential. The industry focus has shifted since 2020 from massive solar farms to rooftop solar, which made up more than half of China’s newly installed capacity last year. The transition has strong policy support—an official plan for peaking CO2 emissions in urban and rural construction in July 2022 called for rooftop solar to be fitted on half of new public buildings and factories under construction by 2025.

A new dawn?

No other country has done as much to pave the way for a solar-powered future as China. Beijing went all in on solar manufacturing and now boasts a world-class industry that appears unbeatable. “Several policies such as the US Inflation Reduction Act and the European Commission’s Net-Zero Industry Act have been introduced by the West to promote local manufacturing of solar power components, but unless they make really serious investments in the solar industry in the coming years, it will be an uphill battle for the West to challenge China,” says Jin.

While China looks dominant, it is the frontrunner in a global industry that has seen different leaders over the decades. “China has the world’s most integrated solar manufacturing bases and most experience,” says Chase. “But before China did, it was the US, and before that Japan. Who knows what’s next?”

Similar to the shakeout a decade ago, industry consolidation is looming as recent trends like the polysilicon price spike correct themselves and competition intensifies. “The market will continue to grow but compete viciously, and there will probably be some bankruptcies,” says Chase. “Solar manufacturing can sometimes be a terrible business to be in and often loses money.” Haugwitz is confident that Chinese solar will only go “up, up, up,” but agrees it will be reshaped. “China will lead globally no doubt, but the industrial landscape will change. You have incumbent companies being challenged by new contenders at home and abroad. The story’s not over.”