A hurdle too high?

According to China sports expert Mark Dreyer, political support for the sports industry in China can be a double-edged sword

The one question I’ve been asked more than anything else in China is why the country appears unable to find 11 decent (male) football players despite its huge population of 1.4 billion. On the surface, it’s a headscratcher; but dig a little deeper and it reveals a number of things.

First and foremost, Chinese people care about football. My time in China has been bookended by two Olympic Games—in 2008 and 2022—and the nation is full of sports fans, with football at, or near, the top of the list. But while sporting success for China at the Olympics has been so bountiful as to become almost routine, success in football has remained puzzlingly elusive. China’s women reached the final of the World Cup in 1999, but 24 years later, China has never made it past the quarterfinal stage.

Meanwhile, the so-called “golden age” of the men’s team came in that same era, with their sole appearance at the FIFA World Cup in 2002. They lost all three games, by a combined score of 9-0. It’s been downhill ever since.

World Cup love affair

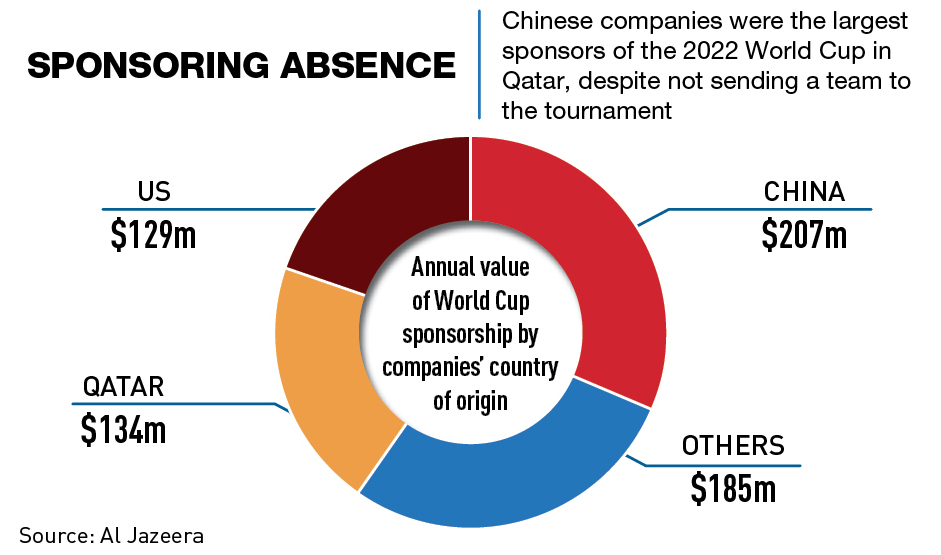

Chinese sponsors collectively spent $1.4 billion, or one dollar for each of its citizens, on advertising at the Qatar World Cup last year—more than any other country—but that spending is underpinned by the country’s love of the sport rather than the success of its team.

Chinese companies sponsor the World Cup for a variety of reasons, including global brand exposure, overseas business opportunities, national pride and more, but imagine how much more attractive the tournament would be for companies such as Wanda, Hisense, Mengniu and Vivo if a Chinese team was not just participating, but actually flourishing there?

The country’s next chance will come for the women later in 2023 at the Women’s World Cup in Australia and New Zealand, while the men will aim to qualify for the 2026 tournament in North America. The men’s tournament will be expanded from 32 to 48 teams, meaning that Asian teams will have roughly double the number of allocated spaces. That should, in theory, mean China has a dramatically improved chance of qualifying for the tournament, but I would estimate those chances at no more than 50-50, given their current standing in Asia and performance trajectory.

Sports, politics, and business

One of the things that has fascinated me during my time studying the sports industry here—and is a central theme of my book Sporting Superpower—is the interwoven threads of sports, politics and business. You can see examples of this in almost any sport, but football provides some of the most obvious ones.

Unfortunately, football clubs in China have tended to have failing business models. Unlike their European counterparts, the usual revenue streams, which include TV broadcast fees, ticket sales, merchandise and sponsorship, don’t add up to nearly enough in China to cover the expense of a club’s wage bill and running costs. But what they do have in their favor is the support of a significant entity, typically a local government, state-owned enterprise, or property conglomerate, and the political capital gained by bankrolling a club has historically more than made up for the lack in organic revenue.

In 2015, China rolled out an ambitious plan, complete with long-term targets, to overhaul its football industry, and this was widely believed to have the personal support of Chinese leader Xi Jinping. As a result, money poured into the sector from all sides. After emerging from a period that had been blighted by match-fixing, football was suddenly in favor and everyone wanted a piece of the action.

Losing its luster

But even before the pandemic began three years ago, the sport had begun to lose its shine. In the build-up to the 2022 Beijing Olympics, winter sports—not football—had become the most favored part of the sports industry, and as investors looked to gain their political capital elsewhere, the only thing football had to fall back on were its failing business models.

Fast forward to today, after three seasons of spectator-less matches due to stringent pandemic restrictions, and football in China is once again on the brink, with clubs broke or bankrupt and a wide-ranging corruption investigation purging senior figures that include former national team player and manager Li Tie and Chinese Football Association (CFA) chairman Chen Xuyuan. Against that backdrop, China’s chances of qualifying for the 2026 World Cup look very bleak indeed.

“Each time the CFA, professional clubs and academies are ‘cleansed’,” says Rowan Simons, “it chops the top of China’s football pyramid clean off. All that is left is the foundation, where people love the game so much they still want to play.” Simons runs China ClubFootball, a network of junior football academies, and has been preaching the values of grassroots football in China for well over two decades.

“World football has fallen in and out of love with China many times over the last 40 years, while seldom addressing the needs of football’s core base,” he says. “Once the Li Tie case reaches its conclusion, the grassroots will be all that is left with value—yet again. If we do not start there, then where?”

Double-edged sword

Political support in China can be a double-edged sword for the sports industry. For example, having a national football association that’s controlled by the government—as the CFA appears to be—directly contravenes FIFA’s governing statutes. Additionally, when the country’s leadership stresses the importance of the successful development of football, that also places an extraordinary amount of pressure on senior figures in the sport to achieve their goals.

But the government’s significant role in shaping the sports industry also paves the way for many of the top sports organizations and national teams to achieve success on the global stage. The most obvious example is in Olympic sports, where Chinese budgets and resource allocation for its elite athletes are the envy of the world.

This relationship between politics, business and sport in China is like a marriage of convenience. The government uses sports to promote its political agenda as success on the global stage boosts national pride and soft power; businesses, meanwhile, can use sports as a way to increase their profits and gain political influence; and athletes and sports organizations navigate these political and business interests to achieve their own sporting objectives—winning gold medals.

The 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics saw a record-breaking performance from the Chinese team, winning nine gold medals—four more than they’d ever won before at a Winter Games. But with the Olympics now complete, the political incentives have vanished. As a result, the most recent winter sports season has been disastrous for China on the World Cup circuit with an almost total lack of success and a depleted team across the board. The Olympics last year showed what China can achieve when the political will exists; this year has indicated the opposite.

But there have been plenty of longer-lasting benefits that have resulted from China’s 2014 plan to build the largest sports industry in the world. There has been impressive progress in winter sports involvement at the amateur levels, even though it may have fallen short of the “three-hundred-million participants” desired by the government.

In the past, sporting pursuits at the recreational level were seen as a distraction to more important things, such as academic study. But the last decade has seen a steady rise in sporting participation at all levels, notably in areas like running and fitness. This shift towards healthier and more active lifestyles, as well as rising per capita disposable income, has meant an increase in participation. Overall, this trend ticks many boxes, across political, financial and sporting spectrums.

Re-engaging the world

Looking ahead, China’s biggest task if its sports industry is to continue to grow, will be to re-engage with international sporting federations, leagues and teams, now that COVID-era restrictions are finally a thing of the past. Where once those organizations were tripping over themselves to get a foothold in the China market, an increasingly uncertain geopolitical environment coupled with an exploration of alternative markets as China remained closed to the world, means that, today, international sporting events in China are few and far between.

Formula 1 now has a bona fide Chinese star in driver Zhou Guanyu, who is as articulate and presentable as he is talented behind the wheel. But as he now enters his second season with the Alfa Romeo team, the Shanghai native remains unable to race in his home country. Throughout the pandemic, China’s prohibitive regulations prevented F1 from coming to Shanghai, where it had raced every year from 2004 to 2019. For this season, shortly after China reopened, Shanghai authorities pleaded with F1 to return in April 2023; but the feeling in the sport was that too much uncertainty remained surrounding a visit to Shanghai in spring—despite the boost they knew the sport would receive due to Zhou’s homecoming.

Meanwhile, the NBA is still struggling to regain its prior dominance in China following a tweet by a Houston Rockets executive in late 2019 that devastated its business here due to a nationalistic backlash. Around the same time, England’s Premier League also saw its China broadcasts abruptly canceled after one player’s social media post about the treatment of Muslims in Xinjiang angered Chinese officials and netizens alike. The Women’s Tennis Association (WTA), which currently has five Chinese women ranked among the world’s Top 65 players, has not yet announced when it plans to return to China following the uproar around the temporary disappearance of retired Chinese player Peng Shuai in 2020.

But despite the challenges that increase the risk of engaging with China, the reality is that its market is simply too large for many to ignore. With 20-year-old tennis player Zheng Qinwen the most likely of China’s players to become a legitimate successor to two-time Grand Slam winner Li Na, the WTA will simply have to find a way to get its Chinese stars playing in front of their country’s adoring fans. And while this year’s Asian Cup was moved from China to Qatar by the Asian Football Confederation, the rescheduled Asian Games in Hangzhou will provide China with another chance to show off its inimitable hosting skills to the world. Interestingly, e-sports—a fast-growing area in which China is at the forefront—will become a full medal sport for the first time in Hangzhou.

“My suggestion is just come to China and stay here,” Shankai Sports CEO Feng Tao told me recently. “There are 300 million [middle-class] consumers. All the international brands need to consider this.”

Domestic brands

Another main reason for optimism about the Chinese sports market is the rise of domestic brands in the sector. Sportswear manufacturer Li-Ning, founded by the former Olympic gymnastics champion Li Ning, was at the forefront of that charge, most notably after Li was chosen to light the flame at the 2008 Olympics—with his company’s shares immediately soaring. But another Chinese company, Anta, now leads the way and recently overtook Adidas for second place in China’s market share, eagerly eyeing Nike for the top spot. With the domestic sports market continuing to grow, Anta, Li-Ning and others are all poised to benefit—and none of them will mind if the international brands get squeezed out of the market, whether for geopolitical reasons or simply waning brand power in the Middle Kingdom.

There’s a long way to go, though, before Chinese sports brands make inroads into the global market. A handful of NBA players have signed lucrative sneaker deals with Chinese shoemakers over the past decade or so, but those have been more about promoting the brand back to a watchful Chinese audience than targeting the NBA’s fans in the US and elsewhere. And those same geopolitical reasons that might squeeze foreign brands out of China could conversely prevent Chinese brands from making headway overseas.

Future success?

China’s relationship with sports is complex, with sports playing a significant role in the country’s national identity and political discourse. While China has achieved considerable international success in certain sports, it has struggled mightily in others, reigniting debate about the best way forward.

Political and financial motivations have often trumped sporting ones—often to the detriment of the sport involved—but if China’s next wave of rising sports stars can help to inspire a new generation of sports participants and consumers, China may yet be able to capitalize on some organically developed success.

Formerly a football reporter with Sky Sports in the UK, Mark Dreyer has been covering sports around the world for more than 20 years, including seven Olympic and Paralympic Games. He has worked with a number of media outlets in China and is regularly asked to comment on the Chinese sports industry for BBC, CNBC, Bloomberg, Financial Times and many others. He runs the China Sports Insider website and co-hosts the China Sports Insider Podcast on the Sinica Network. Mark has been based in China since 2007.

Sporting Superpower: An Insider’s View on China’s Quest to Be the Best, a book that examines the parallel threads of sports, business and politics as China bids to build the world’s largest sports industry, was published in 2022.