Youth unemployment is on the rise globally, but there are factors which make the problem in China unique

With the economy slowing, robots and artificial intelligence (AI) expanding their roles and competition growing for good positions, the reality of life after graduation is stressing out Chinese students even more than their exams.

In 2019, a record number of graduates entered the labor market—8.34 million—according to the state-run People’s Daily, up from 8.2 million in 2018 and significantly higher than the 6.1 million in 2009. Added to that is the slowing growth in the economy, now down to around 6% a year, and a much more cautious approach by companies to taking on new staff.

“I feel quite worried about finding a job after I graduate,” Suyang Jin, a broadcasting student at Nanjing University, told CKGSB Knowledge. “Many of my classmates feel the same way. Companies are often not willing to offer recent university graduates opportunities, as they’re usually looking for people with work experience. I also don’t think there are enough jobs for everyone, because China has such a huge population and there are only a limited number of jobs available.”

Zhenghong Zhang, another student approached by CKGSB Knowledge, agrees. “Finding a job now is difficult.” The 21-year-old student at Southeast University is planning to delay her entry into the job market by pursuing a master’s degree.

“It’s because of the oversupply of job seekers. The population is large, and the number of graduates is increasing each year, but the number of jobs has remained limited. The pressure to compete is therefore also increasing each year,” she says.

The structure

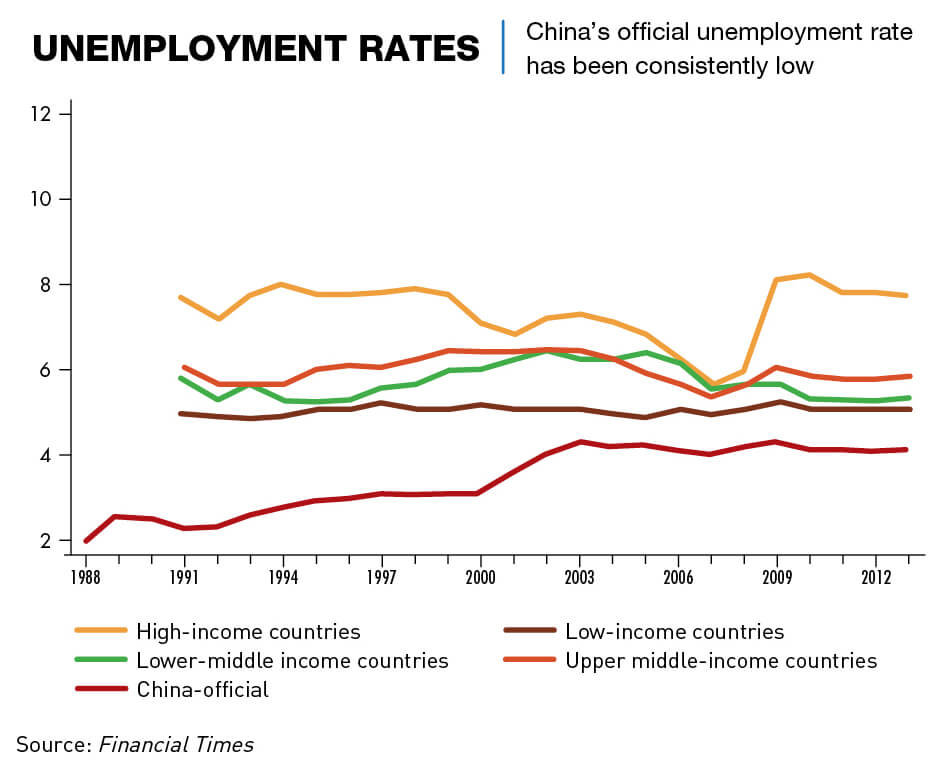

The official unemployment rate, updated quarterly, stood at 3.61% in September 2019, little changed for the past two decades. That number sounds good, especially given China’s huge population, but the true unemployment rate is difficult to peg, with different agencies reporting varying figures over the years.

“The statistical agencies are not good at tracking the unemployment rate,” says Andrew Polk, co-founder of Trivium China, a Beijing-based research consultancy. “It’s partly because it is such a sensitive issue. If unemployment is on the rise, China doesn’t want any easily observable signals. It’s also the most populous country in the world and is still in a way underdeveloped and changing rapidly, so it’s just really hard to measure unemployment.”

Francis Bassolino, managing partner of Alaris Consulting, also raises the question of how to define unemployment in China. “The unemployment rate is really driven by the State’s definition of employment,” he says. “The connection to reality is tenuous.”

“If someone has a job that could be done in one hour but they’re taking eight hours to do it, is that full employment? I’ve seen as many as six people doing the job that a single person should be doing, and I wonder about the long-term viability of that. I don’t believe that the unemployment figures are an accurate reflection of true unemployment in society, which is probably closer to 20% if you use a rational economic metric to calculate it.”

Employment and unemployment rates for graduates are even harder to pin down. The China Institute for Employment Research (CIER) index, reported that in 2018 there were 1.41 positions available for each graduate, down from 1.54 in 2017. But a survey of more than 88,000 Chinese graduates conducted in the early months of 2019 by the online job platform Zhaopin, found that nearly nine in 10 thought it was difficult to find a job.

Employment and unemployment rates for graduates are even harder to pin down. The China Institute for Employment Research (CIER) index, reported that in 2018 there were 1.41 positions available for each graduate, down from 1.54 in 2017. But a survey of more than 88,000 Chinese graduates conducted in the early months of 2019 by the online job platform Zhaopin, found that nearly nine in 10 thought it was difficult to find a job.

The speed with which the economy has changed in recent years contributes to both the unemployment rate and the lack of clarity around the issue. “You see that with young people job-hopping quite frequently, which ultimately contributes to a high level of structural unemployment,” says Polk. “It is common for young people to jump in and out of the workforce and to not necessarily be sitting for months looking for a job.”

The so-called “gig economy”—short-term freelance work with no full-time employment benefits and security—has become a significant factor in China’s graduate job market, with both positive and negative implications.

“The rise of the gig economy has contributed toward a higher level of employment,” adds Polk. “It also relieves some of the unemployment stress that youth may be feeling, because they know that they can take up a quick job in the gig economy to make some money to get by without having to tie themselves down to anything long-term.”

Official reports and anecdotal evidence point to the existence of lots of jobs being available in China’s dynamic economy. The state-run China Daily reporting 7.52 million new jobs being generated in urban areas in the first six months of 2017 alone. But Chinese graduates are facing a much tougher environment compared to that of their peers just a few years ago in terms of solid full-time jobs with good career potential.

“There are many jobs at the lower rungs of the unemployment ladder for those with mediocre to non-existent degrees, but longer-term employment prospects are limited, particularly when you’re looking for jobs that offer upward mobility,” says Bassolino. “Youth unemployment in cities is really a choice because there are plenty of low-skilled jobs around. But I don’t think it’s appreciated how grim the employment world is going to look for the young people of today after they’re 45 years old.”

“There are many jobs at the lower rungs of the unemployment ladder for those with mediocre to non-existent degrees, but longer-term employment prospects are limited, particularly when you’re looking for jobs that offer upward mobility,” says Bassolino. “Youth unemployment in cities is really a choice because there are plenty of low-skilled jobs around. But I don’t think it’s appreciated how grim the employment world is going to look for the young people of today after they’re 45 years old.”

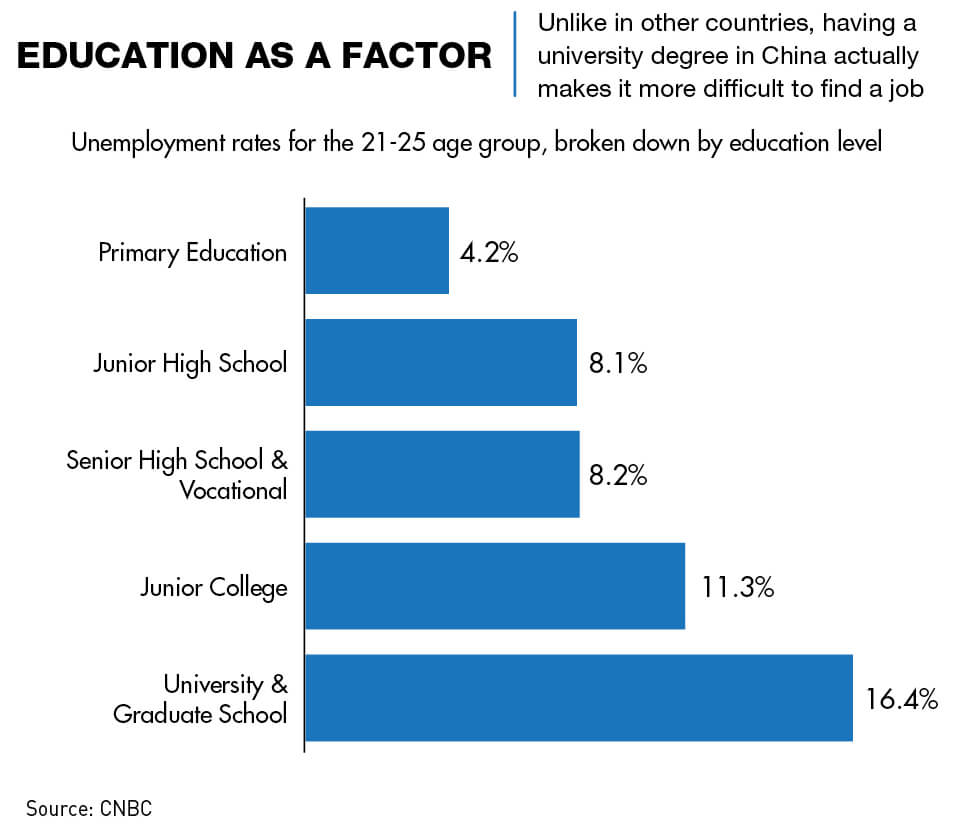

A unique aspect is that unemployment is more prevalent amongst highly educated youth in China than the overall population. Data from the official China Household Finance Survey shows the unemployment rate of university educated youth to be 16.4%, while those with a primary school education is only 4.2%. In other words, the higher the level of education received, the higher the probability of not finding employment or accepting a job. This is in direct contrast with trends in the UK and the US, where higher education is associated with better job prospects.

“There are simply many more university students graduating each year than there are white-collar jobs,” says Polk. “I think it’s more of a structural issue than it is of people having overly lofty career expectations. Literally not enough jobs exist in the right parts of the economy.”

But the graduate unemployment problem is also tempered by complex social factors.

A crisis in the making

With a rapidly aging society and a total workforce that is starting to shrink, China is facing a demographic crisis. In 2018, the old-age dependency ratio, which is the ratio of people 65 and older to people of working age, grew to 16.8%, up from 11.3% in 2008, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. That means that every 100 people of working age are now supporting around 17 retirees, compared to just 11 a decade ago.

The root cause of the demographic crisis is the one-child policy—the official program initiated in the late 1970s by the central government to limit the number of children a family could have. Large parts of the policy were formally relaxed in 2016, but most people in the labor market are only children and bear the weight of caring for parents, grandparents and children alone. On the other hand, only children can look forward to becoming the sole recipients of the assets of their forebears.

“The one-child policy was a double-edged sword,” says Bassolino. “Many young people are set to inherit enormous wealth, mostly in property, especially in first-tier cities and provincial capitals, which allows them not to have to work. But for others, it’s created an undue burden in how they will be responsible for caring for many family members on a single stream of income.”

An automated future

As China develops and upscales its economy, an increasing amount of AI and robotics are being introduced into business activity, which is pushing down the need for human hires in all areas. Accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers, estimates that AI and related technologies, such as autonomous vehicles, drones and robots could displace around 26% of existing jobs over the next two decades, rather higher than their 20% estimate for the UK.

As China develops and upscales its economy, an increasing amount of AI and robotics are being introduced into business activity, which is pushing down the need for human hires in all areas. Accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers, estimates that AI and related technologies, such as autonomous vehicles, drones and robots could displace around 26% of existing jobs over the next two decades, rather higher than their 20% estimate for the UK.

China already has the most manufacturing robots installed of any country in the world, and a third of the global total. That proportion is set to rise in the coming years. “The development of robots and AI will definitely affect the number of jobs available for young people,” says Jin.

On the other hand, PwC’s report says the automation trend could also create more additional jobs by boosting productivity, real income and spending levels. Their estimate is that the net impact could be a boost to employment of around 12%, equivalent to around 90 million additional jobs over the next two decades.

“Part of the reason you have this push into AI and robotics by the government is because they know they have an aging and shrinking workforce,” says Polk. “And they have no choice but to begin replacing people with technology unless they change their immigration policy. My guess is that China will increasingly turn into a more services-oriented economy and it will create more white-collar jobs, while blue-collar jobs will increasingly be done through automation.”

The growth of AI and robots raises the question of whether youth are learning the right skills for the future world of employment.

“In many ways, China is ahead of the game,” says Terence Tse, associate professor of finance at the ESCP Europe Business School’s London campus. “You can see it in how they’re emphasizing new fields of study such as teaching kids how to code. Of course, not everyone becomes a coder or engineer, but it sets them on the path of understanding what coding and algorithms can and cannot do.”

Bassolino, however, disagrees: “Young people will struggle in the job market in the future because the education they’re receiving is not preparing them to add value to society. But overall, AI and robots haven’t affected employment yet, as they’re often used in sectors such as manufacturing where young people don’t want to work anyway. Robots replacing people in the service sector is still a long way off.”

Social factors

The family is another element of the equation. Young people can generally rely upon a high level of support, which means that they don’t necessarily have to take a less-attractive, lower-paying job, but can stay at home until the job market changes and the right job emerges.

The family is another element of the equation. Young people can generally rely upon a high level of support, which means that they don’t necessarily have to take a less-attractive, lower-paying job, but can stay at home until the job market changes and the right job emerges.

“In the West, most young people do not expect their parents to take care of them after they graduate, and so there is a greater sense of urgency to look for a job,” says Tse. “I also believe that the level of independence of kids in the West is higher than in China, meaning that they are typically willing to actually venture out further and find their own path.”

Polk has a similar view. “The family structure in China is very close here, so even if families aren’t particularly wealthy, there is more of a family safety net here than in other countries.” Parents always want to provide for their children, he explains, but that comes with the expectation that, when that child becomes independent and the parents get older, care goes in reverse, with the child becoming responsible for taking care of their parents.

The result is a surprising level of complacency among many young people, which is reflective of the enormous gains that Chinese society has seen over the past few decades. And many are happy to spend time online and disengage from the formal job market.

“If they’re not working, the boys are playing video games and the girls are sending inane gossip back and forth,” says Bassolino. “They are wasting time. There is some productivity in how they create small stores online, which do have the potential to grow, but because it’s such an informal economy, it’s difficult to know what it is worth.”

While there is no solution in sight to China’s fundamental problem of slowing economic growth and growing numbers of graduates, as long as the family system remains supportive, the country will dodge a bullet. And the likelihood is that the importance of the family will remain a solid feature of China’s social landscape well into the future.

“Even if a ‘child’ is now 30 years-old, in the eyes of parents, they are still a baby,” says Tse. “For kids, there is almost always the backup plan of resorting to your parents for help when they run into problems.”