Although constituting a major policy shift, the end of the one-child policy might not help balance the books for China, and its economy.

The announcement of the two-child policy in late October 2015 sent Mary Yang on a roller coaster ride of emotions.

“I was overjoyed when I heard the news. At dinner time that evening, I asked my husband if we should have a second baby, and he was absolutely for it, and we were all happy and excited. For years, we had thought we could not jeopardize his job in the civil service, but here comes the opportunity.”

But that night, overwhelmed by worries, she couldn’t sleep. In her late forties, Mrs Yang was afraid that her pregnancy would be too risky. Moreover, she wasn’t sure if they could afford a second child, given the already high expenses for their ten-year-old son, and she wasn’t sure whether her employer, an insurance company, would keep her job if she did have a second child. By the morning, the couple said they weren’t as certain any more. They have decided to wait a little longer before deciding on what to do.

Like Yang, since China’s announcement that married couples could now have two children, thousands of couples in China are likely to have spent sleepless nights ruminating on the possibility of adding to the family.

The landmark announcement, which came after 37 long years, caught many observers off-guard and was passed by the Chinese legislature in December last year. Oxford demographer Stuart Gietel-Bastern said he was “shaking”, while noted Chinese author Xin Ran, who has written extensively about China’s one-child policy, said she “shed a tear”. Chinese social media went into jubilant overdrive, reflecting the policy’s deep social reverberations.

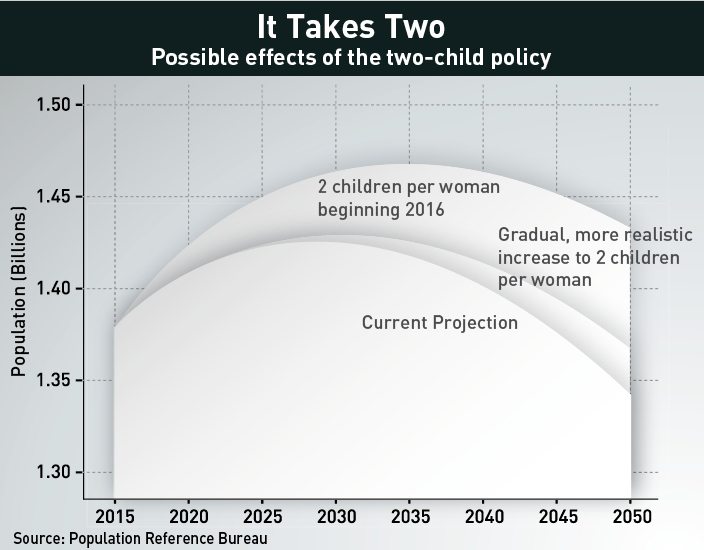

While Chinese authorities cited the official reason for the change as being “intended to balance population development and address the challenge of an ageing population”, their projection that the abolition of the policy would yield a 0.5 percentage point boost in economic growth over the long term, without specifying a time frame, suggested that there were economic motivations behind the end of the one-child policy. But whether it will really deliver a boost in growth for the economy is an open question.

Demographics Askew

While most observers date China’s one-child policy to the late 1970s, China began demographic planning from as early as 1964, when China established its first Birth Planning Commission to lead birth control efforts after China’s population growth re-bounded after the devastating Great Chinese Famine.

As part of China’s 4th Five-Year Plan in 1971, China began setting official goals of reducing population growth and launched the “Later, Longer, Fewer” campaign. The campaign pushed for citizens to marry later—at least after age 25 for women and 27 or 28 for men in the city, and for citizens to have fewer children, with longer time periods between the births of children. During this campaign, there were penalties for those who did not comply, and by 1979 the country’s total fertility rate had halved to 2.7, down from 5.5 in 1970.

But in 1979, in spite of the drastic decline in birth rate in previous years, Deng Xiaoping’s government decided that more drastic action was needed and the one-child policy was officially introduced. According to researchers, action was taken after doomsday scenarios of overpopulation generated in the West found their way to China through Song Jian, a ballistics specialist who had the ears of Chinese leaders.

While Chinese authorities have claimed that the experiment was enormously successful and helped prevent 400 million births, thereby ushering China into an age of economic prosperity by saving resources and preventing overpopulation, the most significant long-term effect of the one-child policy was its sending China’s demographic structure off-kilter.

The fertility rate fell below the replacement rate shortly after 1990, reaching 1.65 children in 1992 according to China’s National Fertility Survey. But it continued plunging, causing China to face the situation of a prematurely and rapidly ageing population.

Driven by the one-child policy, the share of China’s population under the age of 20 fell from 51% in 1970 to 27% by 2010, while the share of people older than 60 years old rose from 7% to 14%. There is increasing pressure on this shrinking population of working adults as the working-age population is estimated to fall by 9% from this year to 2030, according to the UN. In fact, the announcement of the two-child policy was officially justified based on addressing the challenges of an ageing population, according to the Chinese government.

But Lu Bei, a fellow at the University of New South Wales’s Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research says she does not think that the new policy was driven solely by the ticking time bomb of the ageing population.

While she says that fiscal transfer is urgently required to address the budgetary shortfall caused by an increasingly smaller ratio of working adults to pensioners, she thinks that the policy has more long-term aims

“The two-child policy is aimed at solving this fundamental population structure challenge, but it might take more than 50 years to take effect,” she says. “Since fertility change will take a long time to alleviate the demographic structural pressure, I do not think the budget constraint caused by the ageing population is the main reason today for this policy.”

She added that the new policy is “a strategic population policy for future fiscal balance” to “ensure sustainable economic growth.”

Will China Take to Two?

Despite its name, the one-child policy is in fact a misnomer, with a significant group of citizens who were allowed to have a second child. By 2007, a senior official from the National Population and Family Planning Commission claimed that the one-child policy applied only to 36% of residents, reported China Daily.

In her book One Child: The Story of China’s Most Radical Experiment, journalist Mei Fong also shows that there was an indication of a move towards ending the policy during the 2000s, beginning with the folding down of the gargantuan National Population and Family Planning Commission.

The bureaucracy had half a million employees on its payroll, as well as 85 million part-timers involved in everything from recording women’s menstrual cycles, to conducting pharmacological research to enforcement. With the folding of the commission into the health ministry, the policy easing was set in motion.

Official rhetoric also relaxed around the same time, when in February 2008 Zhao Baige, then vice-minister of family planning, told reporters that China would ultimately scrap the one-child policy. The rules were also substantially loosened in November 2013, with an exemption allowing two children for families where one parent is an only child.

These exemptions offer an insight to what China’s fertility rates will look like with the removal of the two-child policy. Yong Cai, a fellow at University of North Carolina’s Carolina Population Center, is convinced that the number of babies born will be far lower than the government’s estimation of 8 million more babies a year.

“Two years ago, China lifted the policy to allow two children for parents who are only children, predicting 2 million extra births. Instead, only 1.5 million of about 11 million qualified applied to have a second child, and an even smaller number of that, roughly half a million went on to have a second child, which suggests that the government’s estimate is quite far off,” he says.

Cai stands by his research from 2007, where he and a group of Chinese demographic scholars conducted a survey of 18,000 women in six counties in Jiangsu province. They found that of 30% of women qualified to have a second child, only 4% went on to have a second child. Shocked by the low figures, he returned to Jiangsu to interview women and returned with the conclusion that the cost of raising children was a significant deterrent to many.

“Of those who had or aspired to have two children, their main distinguishing characteristic was that they could afford a second child, and that they usually had better time flexibility in their job,” he says.

But the case of Yicheng in Shanxi province—one of four towns which quietly allowed its residents to have two children from the beginning of the one-child policy—offers an interesting counter point to Cai’s findings.

While Yicheng is a little poorer than the national average, the town, which at first sight looks like any other small town in China, had a fertility rate of about 0.3 points above the national average in 2000, The Economist reported. Fertility has fallen more slowly in Yicheng, implying that some parents, if given the chance, regardless of wealth, would have more than one child. The estimates of China’s baby boom still remain anyone’s guess, with couples like Mary Yang and her husband unsure of what to do.

Baby Bull Market

The market, however, reacted enthusiastically to the policy’s potential ability to boost consumption. Shares of stroller and car seat maker Goodbaby rose by 7.4% after the announcement, while milk powder producer Biostime saw an increase of 5.5%.

Chinese brokerage Citic Securities also put the predicted the number of births at the high end of estimates, saying in a report that the new policy could bring in six million more new births a year, creating a market worth $55 billion.

Vic Edwards, a visiting fellow in Banking and Finance at the University of New South Wales Business School, highlighted that Australia stood to be the country which would benefit the most in the short term, with increased demand for Australia’s highly sought after pharmaceutical goods, milk powder, eggs and meat.

Meanwhile, local media such as China Daily and the South China Morning Post reported on a surge in demand for larger homes. The Post cited Cai Shiyang, a real estate agent saying that the policy had a “huge” impact on real estate. While larger units used to account for less than 30% of all deals, the policy had greatly altered demand, with half of his deals now made up of larger units.

Xinhua also reported that the year of the monkey, which began on February 8, is considered an auspicious year for babies, which would encourage more parents to have children. Postnatal service providers are reportedly short of well-trained maternity matrons, said Xinhua, which reported that salaries were being doubled with the increasing demand for matrons.

Jin Keyun, a professor of economics at the London School of Economics, says that the new policy will drive China’s consumption growth, noting that boosting domestic consumption has been a longstanding macroeconomic goal of the Chinese government in moving from an export-led growth model to one based on domestic consumption and services.

Citing a 2009 urban household survey comparing families who had twins under the one-child policy and those who had just one child, Jin says that the policy would reduce aggregate savings and drive consumption. Urban households with one child spent an average of 10.6% of total income on education and saved 21.3% of total income, while those with twins spent 17.3% and saved only 12.8% of total income.

“As the number of households with two children increase, the two-child policy is likely to be the most effective way to increase consumption,” she says, adding that while initial sectors such as children’s products would benefit first, other sectors such as housing, life insurance and pharmaceuticals would also see a ramping up in demand.

While David Howden, a professor of business at the Saint Louis University in Madrid, agrees with Jin that Chinese people spend more money on children when they have more, which would result in a decrease in savings and increase in consumption, he is skeptical that the new two-child policy will have much effect in the short run because the Chinese no longer look at children as “savings plans”. That contrasts with people in developing countries, who, instead of paying into social security plans, typically prefer to have their children look after them in old age.

“Typically in developing countries, children are a way to save for retirement… but Chinese people are now reluctant to have many children as they save more of their income in real assets, rather than in the form of children. With undeveloped financial markets and high inflation, Chinese savers put money into real estate and real assets as their only savings vehicle,” he says.

“In China now, there is a bigger demand to have fewer children and to give more opportunities to each child, while they invest in real assets like housing for their retirement,” he adds, noting that he still expects a labor crunch in the future.

Not an Economic Fix

While all experts agree that the scrapping of the one-child policy was well overdue, the majority think it will not have a significant impact on China’s economy.

Most experts point to the fact that the birth of more babies is too late and too little to reverse Chinese’ unbalanced demographics.

Shamel Azmeh, a fellow at the London School of Economics’s (LSE) International Development department, wrote in an LSE blog post that China’s challenge for economic and political stability will be determined by the key issue of economic upgrading from labor intensive manufacturing to higher value-added industries to match the demographic shift. However, he cites World Trade Organization data that the foreign value-added in China’s manufactured exports have increased since the late 2000s, indicating that the process of upgrading China’s industrial abilities has stagnated.

While “relaxing the population policy to boost labor supply” could help to rebalance the dangerous trends of its slowdown in exports and stagnation in upgrading its industrial abilities in manufacturing, Azmeh adds that the step could be seen as being taken too late as China’s labor force will continue to shrink in the coming years, making the need for innovation that much greater.

And while Cai thinks the long-term benefit in demographic balancing is significant, he also hesitates to imply that there will be significant economic impact.

In recent years, China has seen about 16 million births annually, Cai says, estimating that about 10 million more babies could be born in the next three to five years. There could be 2 million more babies annually, bringing the yearly total to about 18 million, although he cautions that his figures are optimistic.

To put that into context, Cai says that even with more than 20 million babies born each year in the 1990s, the impact was not considered substantial. Two or three million more babies will not have a substantial impact, he adds.

“There will be a short-term economic impact, but I really doubt that any economist will say that it will boost GDP growth,” he says. “Economic growth is not so mechanical and is not entirely driven by the extra number of people.”