The recent Uber-Didi merger has ended the two company’s price war for market share, but it may not be a great news to have only one company ruling the entire online car-hailing market.

In transit tech terms, 2012 was a simpler time in China: the Shanghai metro system only had 303 stations (364 today), Segways had not yet been overtaken by hoverboards, and if you wanted to hail a taxi, you had to flap your hand out into the street. But that same year, China’s top ride-hailing service Didi Dache set out on a course of disruption.

San Francisco-based taxi booking firm Uber commenced its international expansion in 2012, and Cheng Wei’s Xiaoju Technologies—the formal name of Didi Dache—was one of a myriad car-hailing mobile apps launched around that time seeking to copy Uber’s model in the world’s biggest market of people needing to go places.

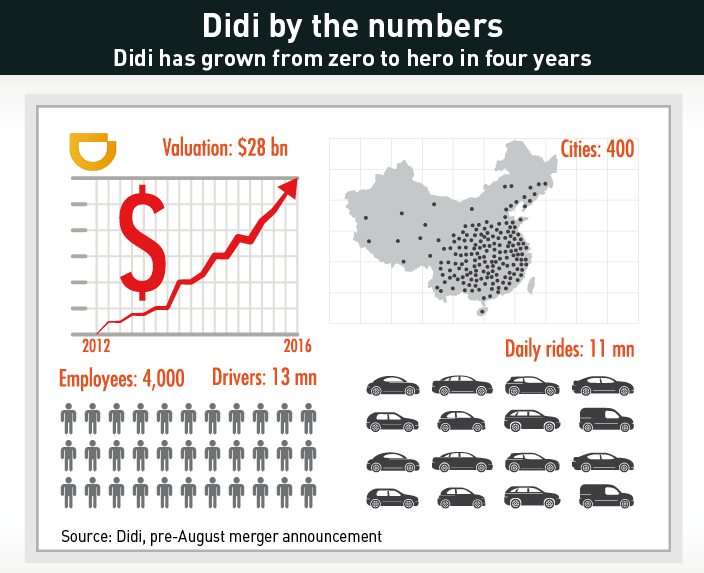

After four years, Didi is just about the last man standing. The company adopted its current name, Didi Chuxing, when it merged with domestic rival Kuaidi Dache in 2015, following an intense struggle. And this August, it announced its pending absorption of Uber China after a bitter marketshare battle that in 2015 bled both companies of over $1 billion each. The proposed marriage will create a company valued at $36 billion, with investors including Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent, China’s tech company trifecta known as BAT, as well as Apple, which invested $1 billion in Didi this June.

There is no doubt that the world of on-demand transit has changed for Chinese people—so much so, that manually hailing a cab can now sometimes be difficult. But Zhang Yi, CEO of third-party market consultancy iMedia, sees all the changes as a net positive.

“The traditional taxi industry does not [meet] Chinese people’s needs any more—Didi spotted the industry’s weak spot,” Zhang Yi says. “Without these hailing apps, Chinese people’s happiness index would be a lot lower.”

But there is a flipside to the convenience. According to CNIT-Research, a Chinese internet data research firm, by Q1 of 2016, Didi had 85.3% of the private-car hailing market while Uber China had 7.8%, which suggests their combined market share after the merger will be over 90%. Market dominance by one player is not necessarily in the interests of consumers.

“There will be only one company ruling the entire online mobility industry, which isn’t exactly great news,” iMedia’s Zhang Yi said.

The Uber-Didi merger deal is currently facing scrutiny from the Chinese authorities and the timeline for completion is unclear. But CEO Cheng Wei is already working on building an ever-more convenient world, with more services and even driverless cars.

4-400-4,000

Ride sharing rose from nothing fast. Didi Dache started as one of over 30 players vying to gain a foothold in China’s transportation market and, as is often the case for startups, the early days were rough.

“In the first month, we knocked on 100 taxi companies’ doors in Beijing and were turned down by all of them,” said Cheng Wei in an address to the National School of Administration. “They wanted to see official documents from the transportation commission but we did not have any.”

The first breakthrough was a small taxi company which owned just 200 cars, but a small window was all it needed. Alongside offline promotions, Didi’s name spread through word-of-mouth, and business began to take off.

The company offered an attractive proposition to both sides of the deal, both supply and demand. For riders, it offered more flexible mobility solutions, enabling them to book rides to designated locations at any time, instead of passively waiting by the side of the road.

For the drivers, it provided new ways to make money. While a few taxi drivers own their cars and register them at state-owned taxi companies, most rent the car from these companies and pay monthly rental fees. So the business is essentially a state-owned enterprise, and drivers have not been faring well in recent years. The basic fare in the year 2000 was RMB 10 in Shanghai, and after 16 years, it has risen by only RMB 4. Before online-booking apps took over the taxi market, the average monthly salary of taxi drivers in Shanghai was approximately RMB 6,000, a bit less than $1,000.

But when drivers use Didi, they say, they can boost their income, in a few cases to as high as RMB 20,000 a month. And private car owners can link into the Didi network as well, providing extra convenience for riders, and extra competition for the drivers of the state-owned taxis.

“If earning RMB 2,500 a month is defined as a job opportunity, Didi has already provided two million of them,” President Jean Liu said at the China Internet Conference in Beijing this year.

What Liu did not say, however, is that those job opportunities have been supported in large part by subsidies aimed at garnering market share. In addition to ride fares, drivers have been receiving bonuses after completing a certain number of orders, premiums during peak times, as well as referrals for new downloads of the app. Riders, too, have received encouragement in the form of subsidized trips, which has at times made using Didi cheaper than taking a cab the old-fashioned way.

But this has not been an affordable strategy for the company, to put it mildly. In the 2013-14 pre-merger subsidy war with Kuaidi Dache, the companies blew through some $700 million combined. Despite the high technology being used, it all amounted to a rather crude strategy of paying for customers and drivers.

Eventually investors from both sides called for it to end, and the two companies announced a merger in February 2015, with subsidies also drawing to a close. As a consequence, ridership dropped by 40% for at least some time, according to a person familiar with the matter.

Even so, after just four years, Didi now has some 4,000 employees (not counting drivers), and has been profitable in close to 300 of the 400 cities in which it operates, according to its Vice-President of Strategy Zhu Jingshi. This success has brought with it anticipation of an IPO, but the company is still unprofitable overall, having suffered a staggering $1.8 billion loss in 2015, according to the top business magazine Caixin.

Analysts, however, are optimistic on Didi’s IPO prospects, but unsure about when it might happen.

“Didi definitely has the need to go public in the next three years,” says Zhang Yi, “Otherwise it would be too difficult to secure the return of investment.”

Road Rage

Bitter rivals, arch nemeses, mortal enemies—after the merger with Kuaidi, Didi Chuxing and Uber China were all of the above.

Stepping over the remains of the US tech giants that have tried and so far failed to gain entry to China’s market—Google, Facebook and Amazon, to name just a few—San Francisco-based Uber Technologies Inc. rode into China in February 2014. Uber’s first move stood in contrast to those who have been forced to stay outside the Great Wall: It created a local unit, Uber China, to help it attract local investors and avoid potential restrictions.

According to Didi’s CEO Cheng Wei at the Yabuli China Entrepreneurs Forum 2015 Summer Summit, an influential gathering of entrepreneurs, the famously aggressive Uber founder, Travis Kalanick, flew from the US to deliver an in-person ultimatum: either give Uber a 40% stake in Didi or prepare for battle. Cheng Wei chose the latter.

Using the same subsidy tactics as before, the rivals initiated a bitter war of attrition to gain market share. During the height of hostilities, Uber gave drivers RMB7,000 for completing 85 orders per week on top of a premium, and Didi’s private-car drivers received as much as double the paid fares.

The bloodletting was spectacular, with Uber losing more than $1 billion in China in 2015, a number not even close to Didi’s losses. The sheer scale of the amounts being thrown away fueled speculation that Didi and Uber China would call a truce and merge, but such talk was dismissed by both sides.

“A merger is simply impossible,” a Didi spokesperson told CKGSB Knowledge in June, which echoed Didi’s position just before its merger with Kuaidi in 2015.

Just weeks later, the rumors were borne out. On August 1st, the two companies announced a deal that will merge the giants—Didi and Uber China’s valuations are $28 billion and $8 billion respectively—into a monster. Under the terms, Uber China agreed to pass on its Chinese operations to Didi, in exchange for one-fifth of the combined company’s stake. Reuters said Didi also will invest $1 billion in Uber Global (already valued at $62.5 billion), Kalannick will serve on Didi’s board, and Didi’s CEO Cheng Wei will join Uber’s board.

In hindsight, the deal seems to have been virtually inevitable. The rivals had shared a few major investors including BlackRock, Hillhouse Capital, and ChinaLife, and shortly before the merger, there were signs from parties on both sides that the bloodbath had become too much to bear. Given Didi’s far greater scale, Uber found itself backed into a corner.

“Uber China was running out of ammunition, was it going to pull out a knife and fight till the death?” says Yuan Yan, and investor at Reid Fund Management. “Why not join the nemesis and share the world while it was still worth a certain value?”

To iMedia’s CEO Zhang Yi, the merger is a win-win, at least on financial terms. “One definitely can’t say that because Uber China surrendered, it means it’s lost,” he says. “Yahoo’s merger with Alibaba won a large return on investment, the same with Uber China. As for Didi, the merger has bolstered its own valuation.”

Some cab drivers see the situation a bit differently, however. “Didi can’t compete with the quality of Uber, so buying them makes sense,” says one Shanghai cab driver.

Hold the Celebration

Despite the seeming finality of the announcement, all may not be over—only the plans have been announced, and the merger may be subject to regulatory review.

Danyang Shen, spokesman for China’s Ministry of Commerce (Mofcom), said on August 2nd that they had not received an application from the two companies. “According to anti-trust regulations and the State Council’s requirements, business operators are obliged to file a case to Mofcom, otherwise a merger cannot be carried out,” he said.

Didi responded quickly, saying that previous major mergers in the internet area have not required a filing, and they are simply following suit. They also cited the lack of profitability as a reason for exemption from regulatory oversight.

“Uber China and Didi are not profitable yet,” Didi said in a statement to Reuters. “Uber China’s turnover in 2015 didn’t meet the RMB400 million requirement for the anti-trust process.”

But industry experts are concerned that the merger will create a new monopoly and may eventually violate anti-trust laws. Both Yuan Yan and Zhang Yi express worries that it is bad news for the growth of the industry.

“It has great significance for both the market and consumers,” Zhang Yi says. “[For] the online mobility industry, there will probably only be one company ruling the entire space whereas there used to be several major players. [For] customers, their options have been reduced from a variety to one.”

Indeed, the subsidies that attracted customers and drivers alike are already disappearing. Some Didi customers posted screenshots of price hikes on Weibo, suggesting they were already feeling the effects. And when Didi and Uber China lowered their subsidies earlier this year, the action was met with anger amongst drivers who demonstrated in Beijing and Guangzhou, a situation that could conceivably recur.

“Shanghai has around 70,000 taxis, and I’d say there are now 250,000, maybe more than 300,000 cars, working the same market,” says another Shanghai cab driver. “But the rice bowl is the same size.”

Eyeing the Bigger Picture

One way of keeping everyone happy may be to offer new services, and in this Didi is well ahead of the curve. Since the merger with Kuaidi, Didi has introduced new services nearly every month—Hitch (ride-sharing), Chauffeur, Didi Bus, Didi Test Drive, and Didi Enterprise to name but a few.

The Uber-Didi merger will very likely lead to even more initiatives, with Kalanick saying the deal “frees up substantial resources for bold initiatives focused on the future of cities.” He links it with everything from “self-driving technology to the future of food and logistics.”

Self-driving cars have perhaps received the most attention—Apple’s pre-merger investment in Didi was made with this in mind—but that still seems to be a development that will take more time to come to fruition.

“Most car manufacturers including BMW have announced their predictions on this subject—they won’t go into mass production for another 10-15 years,” says Dr. Tang Huayin, who works in research and development in the automotive industry. “Didi doesn’t have any apparent advantage. There are so many areas where it would have to rely on others—the making of cars, self-driving sensors, algorithms. Having said that, their biggest strength is dominance of the end-user market.”

What is more certain is that CEO Cheng Wei has a big vision, and experts have compared his nurturing strategy with that of Alibaba, a company that spent 10 years losing money before delivering the largest IPO in history.

During a speech at the China National School of Administration, Cheng Wei gave his prediction of Didi’s next hurdle, “If [the] “internet of things” is at the beginning of an internet company’s agenda, after it has gathered a huge amount of data and has more advanced algorithms, it will move on to artificial intelligence.”

Where artificial intelligence might takes things for this business, who knows. But seen from an individual’s point of view, one cannot deny that the ride-hailing app revolution has changed the meaning of ‘getting around’ for the whole nation, just as the company name ‘Chuxing’ suggests in Chinese.

“I no longer have to desperately wait on curbs during peak hour,” a 25-year-old Didi user, Hangwei Wu, says. “My life has less uncertainty now.”