Plans to integrate Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei into a larger region nicknamed JingJinJi face obstacles central to China’s future growth.

When the dawn of post-imperial China broke the horizon in 1911, the grandest building in Beijing was still the Forbidden City’s 35-meter-tall Hall of Supreme Harmony, and Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei were still a single province.

Just over a century later the gleaming glass of the China World Trade Center’s Tower III stands at 330 meters in the capital’s Central Business District. But all too often its top floors are obscured by impenetrable haze. On a rare blue-sky day the view from the top affords a vista of gridlocked ring roads radiating out toward a seventh ring of garbage dumps and onward to a far less prosperous periphery.

Hence the drive to decongest the capital’s core by pushing the municipal government’s headquarters out to Tongzhou district, bordering the municipality of Tianjin and the push for greater public transportation links with surrounding Hebei province, along with calls for more specialized, coordinated development and environmental protection by the three. It’s all part of the ambitious “Jing-Jin-Ji” (or JingJinJi) plan to integrate Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei into a single, massive urban corridor.

The project has backing from President Xi Jinping himself, and a regional approach will undoubtedly be necessary to address the mounting industrialization-based ills of Beijing and its neighbors. Yet differences in economic structure, political realities and the tall walls of bureaucracy could stall grand plans meant to deal with difficulties at the local level that are now also facing China as a whole.

“The thing is, when you look at the flow of resources, the money follows power, people follow the money and pollution follows people,” says Qi Ye, Director of the Brookings-Tsinghua Center. Ye notes that unlike China’s other urban corridors in the Yangtze River and Pearl River deltas, both political and economic power in the JingJinJi area are tremendously unbalanced. “It’s no wonder you see so much pollution concentrated in a small area like in Beijing.”

But if policymakers can’t overcome such issues writ small within the region, it’s unclear how they could hope to handle economic rebalancing on a national scale. As goes JingJinJi, so, too, may go China.

Historic (Ab)normality

The history of JingJinJi hearkens back to the Ming and Qing dynasties, under which Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei were known as a single province (“Zhili”, meaning “directly ruled” by the imperial state) having roughly analogous borders. But in 1928 the Republic of China designated Beijing and Tianjin as special municipalities, with most of the surrounding territory reconstituted into the province of Hebei.

And while JingJinJi now enjoys the policy planning spotlight, the concept is over a decade old. The phrase—which refers to the respective administrative abbreviations of Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei—had entered the state media lexicon by as early as March 2004, when a report from the overseas edition of the People’s Daily, the newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party, asserted the central government’s powerful National Development and Reform Commission had convened a joint meeting on the topic with leaders from all three administrative districts.

But it was only in February of 2014 that the plan was revived by Xi Jinping’s call for integrated development of the region during a symposium in Beijing. By March the state-run paper China Daily was reporting on a “new plan” for integration “expected to ease the air, water and transportation problems” of Beijing and Tianjin. The former would also “relocate less important industries and divert population to neighboring cities in Hebei, to ease population pressure in the capital and beef up the competitiveness of its surrounding areas.”

Structural Integrity

Such bulking up is urgently needed: Beijing and Tianjin both had nominal gross domestic product (GDP) growth above 7.5% in the first half of 2015, but Hebei saw growth fall to less than 2% for the period—low enough for Andrew Batson and Chen Long of research firm Gavekal Dragonomics to write that it and five other northern provinces “are unarguably in recession”.

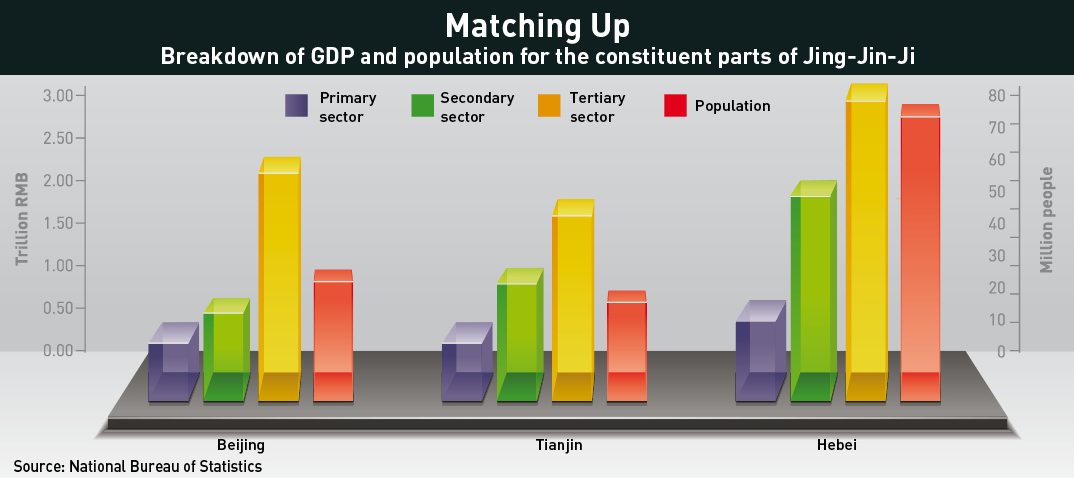

The divergence stems in part from economic structure: nearly 80% of Beijing’s growth comes from the services sector; Tianjin’s is split roughly in equal measure between services and high-end manufacturing. But Hebei relies on manufacturing for over half of its growth, much of it heavy industry, and in 2014 over 11% of its GDP still came from the primary sector, namely grain farms and coal mines.

Wang Jinmin, an assistant professor at the University of Nottingham’s School of Contemporary Chinese Studies whose research focus includes industrial clusters in China, says that this traditional heavy industrial base sets JingJinJi apart from the river delta economies.

But China is now transitioning away from heavy industry and exports and toward a consumption and services-based economy. Thus, in Hebei, Wang says, “the government intends to push for industrial upgrades in the area to stimulate structural change,” hopefully spurring more rapid development of the private sector.

Yet while its economy is already larger than those of Beijing and Tianjin in absolute terms, Hebei’s per capita GDP lags the national average and trails woefully behind its neighbors’. That’s because its residents account for two-thirds of JingJinJi’s total population of 110 million people, and 40% of the province’s population live in areas that are officially designated as rural.

Polycentric Thinking

That distribution puts the lie to claims in anglophone media that JingJinJi will soon constitute a massive, unified “megacity” of unprecedented scale. But this potential for increased urbanization and Hebei’s many million-plus population municipalities—relatively small, for China—may open the door for the region to move beyond its Beijing-facing monocentricity, says Daniel Hedglin, an urban planner with experience in Shanghai and co-founder of the China Urban Development Blog.

“They’re looking to think about the region in polycentric centers that are a little bit larger and much more specialized,” Hedglin says. Which might be harder than it sounds .

“China, in general, from a planning perspective doesn’t really do collaboration well across different municipality lines,” Hedglin says. With few exceptions, regional integration requires a level of cooperation anathema to most mainland cities whose officials’ chief concerned is competing for economic opportunities.

Based on official announcements thus far, coordination under the JingJinJi rubric would mean a continued focus on technology and cultural industries for Beijing, while Tianjin would ratchet up its research and high-value-added manufacturing sectors in addition to its role as a major port.

While state media reports have made vague references to new infrastructure, residential developments and light manufacturing in the province, Hedglin says that “to this point it’s still a bit mysterious how Hebei plays into the Jing-Jin-Ji region.”

Known Knowns

There are, however, a few firm details, mostly about the “Jing” of the eponymous plan.

Current plans demand that Beijing’s population growth be capped at only 1 million more residents, with its central districts to be depopulated by 15%. Municipal governance will move to the outer district of Tongzhou, near Tianjin, aided by a broader transport infrastructure overhaul.

Details on that initiative arrived in July, when Beijing’s municipal transport commission laid out a hypothetical 1,000 kilometers of track for an expanded subway, train and high-speed rail system reaching as far as the city of Baoding, about as far southwest of the capital as Tianjin is to its southeast. Xinhua framed the expansion as a first step in spreading out Beijing’s intensely dense population.

Wang points out that such expansion could also boost the proximity benefits for Hebei, which he expects could see an inflow of other industries that crowd the capital, such as hospitals and other medical sector businesses. He also believes Beijing could encourage further expansion of its top-tier higher education institutions in Hebei, which in turn could attract attention (and hopefully investment) from the tech industry.

But there will likely be limits on what can escape Beijing’s gravitational pull: in July Chinese business magazine Caijing reported that the city of Baoding would become China’s auxiliary political capital—a claim officials and state media promptly and strenuously denied as property prices rose regardless.

Even the most recent official pronouncements on Hebei’s role have been remarkably vague. In August Xinhua cited a document issued by a leading group for coordinated development of the JingJinJi region as stating that Hebei would be an “important national base for trade and logistics” (it already is) and “an experimental area for industrial transition and upgrading”.

Daunting Difficulties

Such grandiose description may resonate with the ambitious idea of a third economic corridor in China’s northeast, but coastal cites in the region are vulnerable to sea level rises spurred by climate change—Tianjin especially. A mere three-meter rise—possible within the next 50 years according to one recent climatological study—could put much of the city’s center and all of its new coastal development projects underwater.

Yet, somewhat ironically, Beijing, Hebei and Tianjin are also among the seven of China’s administrative districts that run a water deficit, in which water withdrawals exceed renewable resources, according to China Water Risk. In fact, the groundwater level of the North China Plain has fallen by nearly two-thirds since the 1970s, when economic reforms began. Even what’s left is often unusable thanks to pollution: a 2013 survey by the Ministry of Land Resources showed more that 70% of the plain’s groundwater wasn’t fit for human contact. Hedglin is skeptical of the idea that pushing unwanted industries out of Beijing and into Hebei will bring ecological and economic gains.

“I get a little nervous that what they’re talking about by moving the factories out of Beijing isn’t necessarily trying to just spread economic growth across the region,” Hedglin says, “that it’s trying to move it away from the city center so that it’s less embarrassing that Beijing has these pollution problems.”

That seems to be how officials in Hebei see things. In April 2014 one district official from the city of Chengde told the state-run newspaper China Real Estate Business that the first wave of companies leaving Beijing for Hebei and Tianjin were all heavy polluting and high-energy consuming: “That kind of company will be a burden no matter where they end up, so right now neither Hebei nor Tianjin is eager to take them in.”

While simply making more land accessible for use outside of Beijing through better transport infrastructure may provide some short-term relief, Hedglin also worries that those same channels could eventually enable inflows to the capital’s urban core by suburban commuters who eventually decide that the next step of success is life in Beijing.

Ye, at the Brookings-Tsinghua Center, is likewise skeptical of the idea that Hebei’s workforce can transition to light manufacturing as easily as has been suggested. “It’s not realistic to expect steel mill factory workers will go to a high tech company, a high-tech industry,” he says.

Green Shoots?

Instead, Ye recommends a counterintuitive path forward for a province known chiefly in China for pollution and low wages—going back to the farm.

“I think there’s a really great opportunity for developing high quality and high-tech agriculture in this region,” he says—and not just the grains it already grows. With the support of complementary tech and research and development from Beijing and Tianjin, respectively, Hebei’s miners and steelworkers could engage in large-scale farming of vegetables and other produce, bringing in far higher returns on investment than government-subsidized corn.

“This is an area with huge demand for high-quality food, and these kinds of gaps tend to be filled by products from other regions,” Ye says. “Why not Hebei?”

But whatever sectors form Hebei’s new economic bedrock, its provincial government’s policies will play a key role in facilitating growth. Nottingham’s Wang suggested Hebei should take its cues from the enterprise booms that are still echoing through China’s southern river deltas, enacting policies that attract more foreign direct investment with the aim of kick-starting potentially disruptive (and lucrative) entrepreneurial ventures.

Micro as Macro

In fact the Pearl River Delta, which had developed organically, faces the opposite problem in its own efforts to better plan development among its nine-city cluster in Guangdong province. Peter T.Y. Cheung, an associate professor at Hong Kong University’s Department of Politics and Public Administration who has studied the delta’s development extensively, says that decentralization and an embrace of reforms empowered cities in the cluster, including Shenzhen and Guangzhou, “so it’s difficult for the provincial government to coordinate them after two decades of reform.”

But he said plans in both regions were responding to a problem of how officials have long been competitively evaluated for promotion based on economic growth, a game in which political positioning is key. A study of administrative hierarchy in China, published in the April edition of the Chinese Journal of Urban and Environmental Studies, found that after examining hundreds of cities and thousands of towns that the higher a city’s rank, the faster its growth. In other words, the developmental inequality JingJinJi seeks to address is a microcosm of a broader national issue.

Indeed, no district ranks higher than Beijing, and few lie lower than Hebei. But Cheung also points out that in 2014 the State Council set up a team to promote regional integration and appointed Zhang Gaoli, China’s vice premier and a member of the party politburo’s powerful standing committee, to lead it.

That clout could prove vital to the success of JingJinJi—though coordination will still require a new approach and unprecedented level of cooperation that won’t likely come easy, regardless of who is in charge. Most vitally, if Hebei is only ever a dumping ground for unwanted industries from Beijing there can be little hope of real and sustainable integration. But while the obstacles are legion, the JingJinJi integration plan has at least recognized one key truth: the region will rise, or fall, together.