Dating back to 1953, China’s system of five-year plans has long been dismissed as anachronistic, but it remains crucial to guidance of the economy.

China’s state media aren’t known as a source of viral internet content, but when Xinhua quietly released a video on Twitter purporting to explain the Shisanwu, or China’s 13th Five-Year Plan (FYP), they managed to create just that, with the video quickly becoming the talk of both veteran China watchers and the general public alike.

For anyone unfamiliar with the video’s cavalcade of cartoon images and quirky self-parody, the overall impression it creates is that of a diligent government applying expertise and deep public spiritedness to the full range of China’s challenges. For completeness, the video features a diplodocus that looks only marginally less confused than most viewers must have been by the time it strolled into view. Perhaps no one pointed out to him that he was supposed to symbolize China’s growth throughout the 12th FYP’s cycle.

In the more sober world of public policy, the video clearly tries to conjure public interest in China’s exhaustive planning cycle, which reached an important milestone on October 26 to 29 when the National Development and Reform Commission presented the ‘Consultative Draft’ of China’s 13th FYP to the 5th Plenary session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China.

Somewhere between the pulsating tweeness of the video and the ever evolving bureaucracy it describes, the three-day meeting marked the point when the many layers of China’s governing system came into alignment, and commenced an official process which will end, in March 2016, by producing the first full FYP issued under Xi Jinping’s leadership, giving an important insight into the strategic thinking of the current administration.

Described in the South China Morning Post as a ‘vestige of a bygone Soviet age’, FYPs continue to occupy a central place in China’s complex system of governance. For just as China’s economy has reformed and adapted in the last 37 years, so too has their planning framework. Indeed, there are clear signs that planning will remain an indispensable component of Chinese economic and political development for many years to come.

Ideology Interrupted

Planning, it was once believed, would eliminate the inefficiencies of competition that supposedly characterizes free-market economies, making socialist economies comparatively more efficient and productive. It was this notion of greater productivity, and not imminent nuclear conflict, that prompted Nikita Khrushchev’s famous aperçu “we will bury you” when referring to the capitalist West. And it is easy to forget that in the 1950s and 60s the Soviet Union grew at over 5% per year, compared with the US trend of nearer 2% over the same period.

The Soviet Union’s eventual problems with inefficiencies and poor capital allocation ultimately contributed to their collapse and disintegration. Since when, the widespread belief has been that formerly socialist economies would ‘transition’ away from planning with the market leading the way towards an innovative future of vastly expanded consumer choice and happiness.

Until recently, this was believed to be the path China had taken since the era of Deng Xiaoping, who implied an ambivalence to socialist economics with his famous fable of different colored cats nevertheless both catching mice. But has the collapse of the Soviet Union given planning an unjustifiably bad press?

Planning Socialism

Leslie Young, Professor of Economics at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, clearly thinks so. He makes the point that despite well-known problems during the pre-1978 period of administrative planning in China, between “1952-1978, China achieved a real growth rate per capita of 3% per annum, which is comparable [to] that of the US over the same period.” He adds that, “central planning was the fastest way for China to mobilize capital and labor for industrialization.”

Furthermore, he thinks that planning has latterly “provided a useful guidesheet for a complex transition, while allowing room for judgment by the leaders of enterprises and local governments.” Young goes on to suggest that many of the problems experienced by the former Soviet Union in the 1990s resulted from an absence of sufficient planning.

“Russia’s switch from central planning to a market economy in the 1990s was aborted by its failure to build … a tax system to extract revenue to fund the state, financial institutions to channel savings into investment, plus accounting and legal institutions to ensure good corporate governance,” he says.

Given the Chinese leadership’s known sensitivity to the fate of the Soviet Union, what becomes clear is that they see planning as a key element of any transition away from socialist economics, suggesting that the great mistake China watchers make is not to distinguish between the socialist economics of the past and the strategic direction of the future, or to realize that planning lies at the heart of both.

And that is a view elaborated by a Chinese International Relations academic in Shanghai, who declined to be named due to sensitivities of talking to the media, according to whom China “is so big with so many things happening, that although you can’t always make things work exactly as planned, you have to have a plan.”

From Jihua to Guihua

Nor is planning simply a necessary feature of China’s size. It is also a key aspect of its politics. One important characteristic of the Chinese state, and a reason why it is unlikely simply to replicate the development path of other Asian states, is the centrality of the Chinese Communist Party to its functioning. In most other countries, certainly in democratic states, political parties are distinct from the state and take control of existing institutions when they come to power. In China, however, the party provides the key strategic and institutional impulse.

Robert Ash, Professor of Economics and Fellow of the China Institute at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, says that “the formulation of FYPs is a reflection of the government’s continuing determination to set long-term national, strategic priorities.” And it is this strategic focus that allows us to gauge the evolution away from an old-fashioned concept of administrative planning towards a much looser template of objective setting and overall guidance.

Indeed, so familiar have we become with the idea of ‘five-year plans’ that the fact that they have been called ‘Programs’ rather than ‘Plans’ since the early 2000s is often overlooked. Not only this, but the Chinese word for plan was altered from ‘jihua’ to ‘guihua’ with the publication of the 11th Program in 2006. The latter word has a looser connotation more often translated as ‘guideline’ than plan.

This, according to Ash, is more than mere rhetoric. “Of course there is rhetoric, there is a lot of rhetoric, but there’s a lot more than that. I say that because the change from jihua to guihua was a very definitive statement.” A statement he believes strongly suggested that the CCP “really have abandoned administrative planning” and instead signaled the arrival of a “much more open, more transparent, less concealed and more consultative approach” to economic and wider policy formation.

Equally, the notion that plans might be eventually phased out meets with almost universal skepticism. The Shanghai academic says quite categorically that planning “has definitely not diminished. It has evolved.” He further clarified that “it’s one of those things you associate with the role of the government itself” going on to outline that “on the one hand it sets guidelines for what the government and the whole country should do, on the other hand it’s really important as an indicator to tell people ‘look we are still planning.’”

In this, the Shanghai academic makes a distinction between the symbolic and the functional aspects of planning, even going so far as suggesting the eventual realization of planning objectives is less important than the symbolism of articulating them. “I don’t think the plan actually always works” but “it is really symbolic for the central government to have these FYPs” showing that what “will definitely not change is how much the government wants to control what is going on.

Equally, the predominant view of planning as an aspect of socialist economics neglects the vital role planning played in the development of other key, non-socialist Asian economies. In Japan, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) was until the 1980s one of the most powerful Japanese ministries. And both South Korea and Taiwan made extensive use of planning during their own periods of rapid industrialisation.

An important aspect of this Asian pattern of strong government leadership in economic development was that international capital markets were not liberalised until the 1980s, which meant that governments had a key role to play in the allocation of investment capital. Therefore China’s ongoing plan to liberalize its capital markets carries implications for its planning framework given that capital allocation is one of the principal tools of economic control.

Number 12

Ash offers a further observation about the 11th and 12th plans by highlighting “another semantic change or initiative, of introducing two kinds or categories of initiatives. So there were the binding targets, and there were a small number of those. But there were also a lot more ‘predictive’ targets.” Describing these as the sort of thing the Central Government would “like … to happen but were not 100% confident … will happen or that … must happen.”

And it is in this expanding range of ‘predictive’ measures that we see a natural evolution away from purely economic concerns, which in turn gives the biggest hint of all that these plans or programs are not simply a relic of Soviet-style economics, but a key instrument in the continuing operation of government.

For although much of each plan’s focus remains economic, this may have less to do with old-fashioned socialist economics than the continuing centrality of economic development to China’s strategic direction. In which case, it is only natural that planning should evolve if only as response to the shifting concerns of the Chinese population.

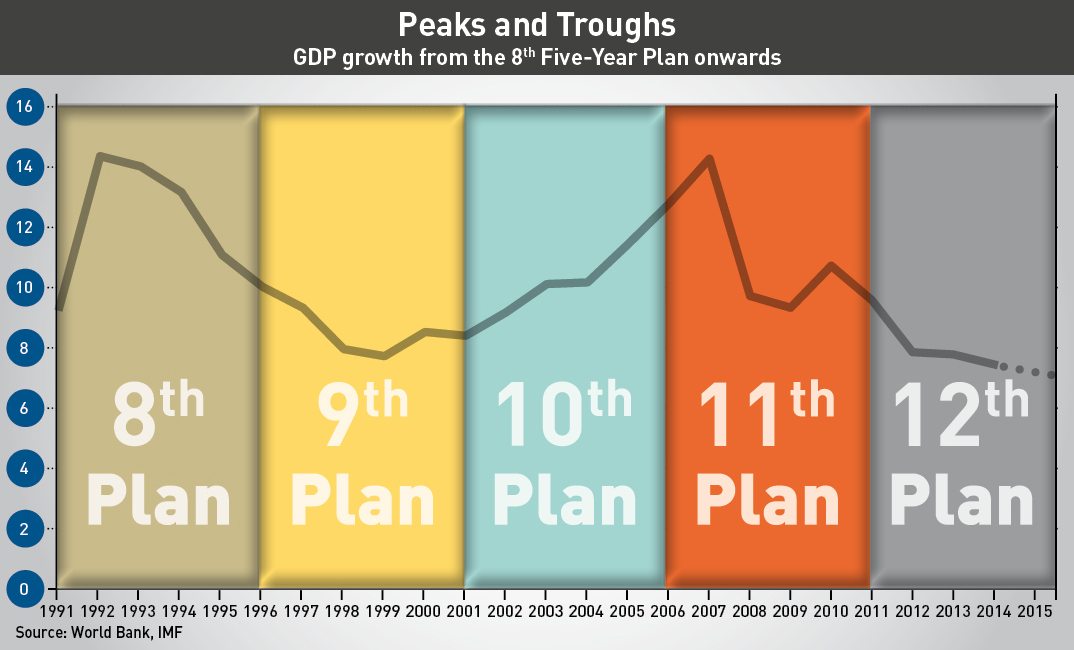

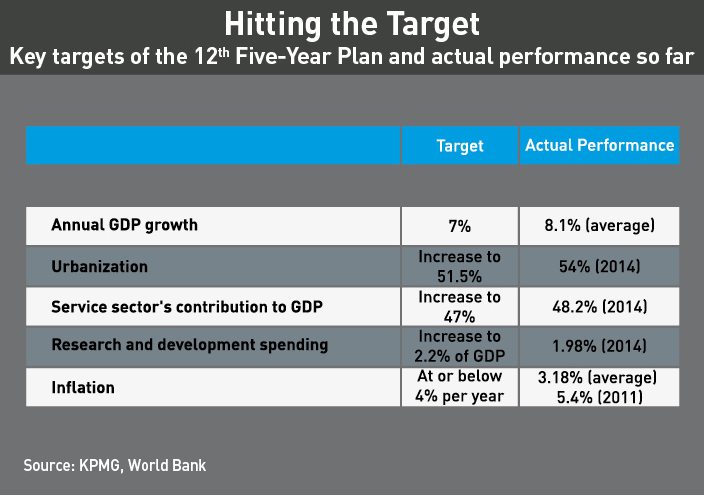

When examining the 12th FYP, it is possible to see that China has delivered on the headline quantitative measures such as growth rates and urbanization, but on other non-economic measures such as pollution-reduction initiatives, results have been disappointing. On some of the conceptual elements, it is hard to gauge whether growth was ‘higher quality’ or ‘more inclusive’, but to echo Ash, it is significant that such aspirations are outlined in the plan.

What is also clear is that China has embarked on some major economic initiatives since the accession of the new leadership in 2012, none of which were explicitly detailed in the 12th plan. In view of which it may be tempting to see the plan as ultimately irrelevant. It is, however, instructive to note how some key initiatives seem to be foreshadowed by the plan. In particular the ‘One Belt, One Road’ is quite obviously complementary to stated elements of the 12th FYP such as developing the Western Regions and ‘moving production inland’, not to mention facilitating the longer term goal of ‘opening up’ and searching for ‘win-win cooperation’ with regional partners.

All of which further reinforces the notion that FYPs have evolved in line with China’s broader economic development. They are ‘programs’ not ‘plans’; they offer ‘guidance’ rather than strict orders, and they constitute a clear strategic signpost both domestically and internationally, leaving room for even very significant changes of direction in pursuit of the overall aims.

Indeed, these changes are such that Sebastian Heilmann, Professor for the Political Economy of China at Trier University in Germany, rejected the idea that the plan is comparable to a ‘blueprint’ back in 2012, referring instead to FYPs as “a recurrent cycle of multi-year, cross-level policy coordination.”

A ‘cycle’ which commences long before the plan is formerly published, and which precipitates what Oliver Melton, Senior Economic Analyst at the Bureau of Intelligence and Research, U.S. Department of State, calls a “cascade of plans” descending through the various regional and provincial levels of government, while being channeled nationally through the many ‘Pillars of Industry’. Or as Ash puts it more succinctly “the planning for the next plan gets under way half way through the previous plan.”

Number 13

What has been revealed so far of the 13th FYP builds on many themes already apparent in Xi Jinping’s tenure. There are no particularly surprising policy departures, with the ‘One Belt, One Road’ policy taking its place alongside the more general aspiration of a ‘more balanced, inclusive and sustainable growth model.’ Space is made for Xi’s ‘China Dream’ and a new emphasis on China’s role in “actively participat[ing] in making international rules.”

The one change that has captured the headlines is the shift to a ‘Two Child Policy’, although this move had been expected for some time. However, to incorporate this social policy shift in the FYP, despite its obvious economic implications, again highlights the extent to which the planning framework has become a catchall strategic statement rather than simply an economic plan.

There are many other aspects to the plan, but again, no dramatic deviations from current expectations. The proposed liberalization of the capital account confirmed for 2020; the restatement of the ‘New Normal’ consensus on growth rates; progress in military reforms already underway; and looming above all is the challenge of overcoming the middle-income trap and achieving domestic prosperity, an aspiration that will be central to verdicts of Xi’s tenure whether it appears explicitly in the plan or not.

Two further changes also confirm political expectations with a reinforced commitment to Xi’s anti-corruption campaign and an annual growth target of not less than 6.5%. In what had at first seemed like an oversight, there was no explicit mention of a growth target, but then on November 3 Xi Jinping announced on his own authority the forecast growth rate, a rate necessary to achieve the Party’s “centenary goal” of per capita income levels doubling from their 2010 figure by 2020.

But even with the importance of that target, what becomes clear is both the extent to which Xi has placed himself, rather than the bureaucracy, at the center of events, inviting the frequent comparisons made between him and those other ‘helmsmen’, Deng and, inevitably, Mao.

Drawbacks and Hurdles

The limitations of detailed administrative planning have been clear for decades and, indeed, China has its own painful experiences to draw upon. But the evolution of planning into a ‘cycle of policy coordination’ raises other issues. In the first place, as Ash says, “you have formulation of plans and you have implementation of plans and they don’t always fit together.”

That in part explains precisely why planning in China has evolved to the looser form of guidance that it comprises today. But beyond this there is also the international dimension. Young outlines that “the basic problem facing China’s planning system today is macroeconomic rather than microeocnomic.” He sees the key problems being that of falling international demand and the investment bubble bursting in Shanghai, the effects of which are understandably hard to plan for.

Interestingly, Young views the solution in terms of an extension of planning into the international realm via the new ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative, which he sees as comparable to “the first era of central planning”, and which requires “political leadership, central coordination of state enterprises and workers, and funding via state banks.”

With this in mind, however, it is worth considering whether state banks and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) can remain central to the Chinese economy as capital controls are gradually lifted as planned. What is clear is that some sectors, such as the new technology sector, are not dominated by SOEs.

Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent are importantly not SOEs and all spring from the sort of innovation that planning simply cannot anticipate. Yet they did emerge, suggesting on the one hand that planning is at least no barrier to innovation, at least in this instance, and indeed that important and growing sectors of the Chinese economy are not centrally concerned with the planning cycle.

Another problem with the current planning cycle in China relates to its evolution beyond simple economic concerns, which directly implicates planning in the never-ending regional tensions that characterizes Chinese politics.

“If the local or provincial government is not in line with the central government—that’s when the plans fail,” says the Shanghai academic. And Ash concurs: “The big problem I see… is the tension within the system between the different levels of government and the different regions.”

Unfortunately this is a problem that is exacerbated by the manner in which capital is currently allocated through state banks towards the big SOEs, precisely because the different regions have different economic profiles, some being dominated by SOEs, and others, particularly in the southern Guangdong region, having far lower SOE activity.

It is worth noting that in the 1980s, after Japan liberalised capital controls, MITI’s role of strategic economic guidance diminished sharply until it was eventually merged into the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), a government department with a much broader and more dispersed, role in 2001.

And lastly, in the non-economic arena, India’s FYPs have long focussed on ameliorating the negative social and environmental consequences of rapid economic development. Priorities which form an increasing component of China’s plans, highlighting the extent to which planning can also be seen as a formal calendar of overall strategic objective setting and reassessment, rather than a merely a blueprint for headline growth.

Planning and Power

Arguably, China’s penchant for planning predates the adoption of socialism—having always been governed by a centralized government bureaucracy—but the end of the Cold War and the rise of ‘globalization’ has persuaded too many people that planning will slowly be phased out. In fact, planning remains central to how China functions, raising the possibility that planning itself, long seen as merely an aspect of socialist economics, is better seen as an indispensable feature of Chinese political culture, whether the cat is ‘black or white’.

The Chinese Ambassador to the UK, Liu Xiaoming, explained on UK television on October 15 that he didn’t “think the definition of China as a communist state is the right one,” going on to say that “the Communist Party provides strong leadership, and enjoys the people’s support.” That reinforces the idea that planning in China has no longer anything to do with socialist economics, but everything to do with strategic direction, and just the plain old exercise of power.

Equally the return of a ‘helmsman’ style of leadership may be a reflection of the scale and nature of the challenges China currently faces. And in this respect the plan is living up to expectations, particular if you assume that the whole affair is simply an opportunity to imprint Xi’s authority on the Party and to therefore consolidate the Party’s role within the state.

In the words of the Shanghai academic, planning is “not just about communist ideology, it’s also about traditional hierarchy and very centralized power.” A conclusion supported by Ash, who says planning “always come[s] back to the role of the party” which “therefore becomes a very political question.”