The slowing auto market is reshaping the automobile industry in China.

Zhou Xiaogang, a resident of the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen, has been planning to purchase a car for some time. A 28-year-old graphic designer, Zhou has already saved around RMB 85,000 ($13,700), a step toward his goal to purchase a new car and an apartment in the city’s suburbs.

On December 29, that dream became much more difficult. Shenzhen officials abruptly announced they would cap the number of new car license plates issued by the city government to 100,000 per year, effective immediately. Most plates will now be allocated either by lottery or auction. Last year, around 500,000 passenger cars were sold in Shenzhen, suggesting demand for plates will far outstrip supply.

The suddenness of the announcement generated much public anger, including from Zhou. “Sure, I’ll register [under the new lottery system],” he says. “But [as to] when I’ll actually be able to buy a car, I have no idea now.”

Shenzhen is the latest city to implement a license plate quota system, following in the footsteps of Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou and others. Officials hope that by limiting the number of new cars on the road they can curb air pollution and traffic congestion, especially as public pressure to combat smog continues to mount. But these restrictions, although well intentioned, risk accelerating the cooling of China’s once red-hot auto market.

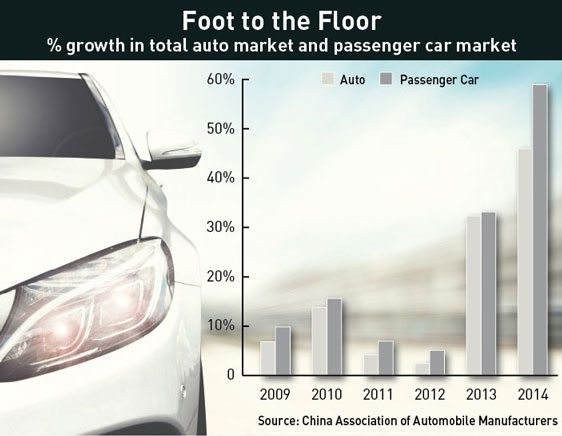

Sales of passenger cars, sport utility vehicles (SUVs) and minivans grew 9.9% nationally to reach 18.9 million in 2014, down from a 15.7% gain in 2013, according to the Chinese Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM), an industry body. Sales of all autos, including commercial vehicles, grew 6.9%, less than half the pace of 2013.

Few in the industry think a return to the go-go years is in the offing. “Everything is normalizing in China: the market growth, the volume growth, the margin growth,” Karsten Engel, BMW’s CEO, told Reuters in November. “The breakneck growth of 30 to 40% will not come back again.”

The slowdown could have wide-ranging ramifications for an industry that has come to rely on Chinese growth. China made up 59% of the global net profit at Volkswagen, 45% at BMW and 37% at General Motors in 2013, according to data complied by IHS Automotive.

What this “new normal” means for various industry players is less certain, however. Chinese car brands will probably take the biggest hit, though in the long run, consolidation will be healthy for the industry. Foreign automakers should fare better, and appear to be investing for the long haul in what is still the world’s fastest-growing major auto market. Even so, they too will need to rethink their approach to the Chinese market.

“The industry really is at an inflection point, and it’s quite a major inflection point,” says John Jullens, a Shanghai-based partner at Strategy&, a consulting firm. “The whole business model is going to have to change.”

End of an Era

Until recently, China was one of the few bright spots in the global auto landscape. Auto sales grew at a compound annual rate of nearly 17% between 2003 and 2014, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers, an accounting firm. China’s auto sales volume overtook the US in 2009, a year when sales surged a blistering 46%.

The China market has seen slumps before, usually as consumers delayed or accelerated purchases in response to government incentives. For instance, the phase-out of a car subsidy scheme led to a paltry 2.5% growth in 2011, but by 2013 it was roaring ahead again at 14%. Today’s slower pace appears here to stay, however.

“The major impact is coming from the macroeconomic environment, which is not very strong,” says Jochen Siebert, founder of JSC Automotive, a consultancy. China’s economy grew around 7.3% in 2014, its slowest pace since 1990. The auto market also correlates strongly with real estate sales; as the property market has cooled, auto sales have fallen in tandem.

Increasingly tough restrictions on license plates are also taking a toll. Last year Beijing lowered its cap on new plates to 150,000 from 240,000 per year. By 2017, the city expects to issue just 90,000 plates to conventional cars, with the rest allocated to new-energy vehicles.

Meanwhile, officials in Shanghai have said they will issue around 100,000 new plates this year; the average auction price of a new plate reached RMB 73,798 ($11,900) in the fourth quarter of 2014. Other cities, such as Guangzhou, Guiyang and Hangzhou, have implemented similar quotas schemes, and more are expected.

The caps limit car demand in those cities, but the way they have been introduced—with little warning, in order to avoid a car-buying rush before restrictions kick in—could have knock-on effects across the country.

The new Shenzhen quota “will have a big psychological impact, because the local city government did not give any lead time or buffer,” says Yale Zhang, Managing Director of AutoForesight, a research firm. If consumers in other cities think they will be next for a quota system, they may push forward their planned car purchases. That would make for a strong first half of 2015, but depress sales in the long term.

Namrita Chow, an analyst at IHS Automotive, thinks the combination of slower economic growth, plate restrictions and Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption drive, which has depressed sales at the premium end of the market, will knock at least another percentage point off passenger car growth this year, marking something of a consensus among industry watchers.

Propping Up the Rest

Less clear is the impact the slowdown will have on automakers.

The hardest hit are most likely to be domestic carmakers, say analysts. These firms cluster at the low end of the market, with models priced at RMB 50,000-100,000 ($8,070-16,140). Their share of the passenger car market fell 2.1% last year to 38.4%, according to CAAM. That share will fall even further as restrictions tighten, possibly to near zero in big cities, reckons Zhang of AutoForesight.

“Consumers will think, ‘I spent so much money on a plate,’ or ‘I went through the lottery system a million times and finally got this car plate, so I need a good brand that I don’t need to upgrade frequently,’” he says. “So even if the original plan was to buy a local [car], after they get the plate they increase their budget—sometimes by double—and buy a foreign-branded car instead.”

He adds that ironically, the quality of Chinese-branded cars is quickly catching up to the big automakers, but consumer perceptions take around a decade to adjust to reality.

Another source of pressure comes from foreign automakers moving down-market. Chinese regulations require foreign car companies introduce local “indigenous” brands, often produced in conjunction with their mandatory local joint venture partner, if they want to expand production capacity in China. The requirements are of the country’s longstanding strategy to trade market access for foreign technology and knowhow, says Jullens of Strategy&.

While the mass-market global automakers such as GM, Volkswagen and others usually sell cars for RMB 100,000-200,000 ($16,140-32,280), the regulations have spurred them to design cheaper models that compete directly with Chinese brands. “There’s a major battle shaping up [at the low end of the market],” says Jullens.

Such competition is probably healthy for the industry in the long run. Jullens explains that when consumers think of Chinese car brands, they tend to think of the big state-owned firms (SAIC Motor, FAW, Dongfeng Motor, Chang’an Automobile and so on) or private players (Chery, Geely, Great Wall, BYD and others). In reality there are more than 170 Chinese automakers, and the bulk of these are a “fat tail” of small, inefficient car companies supported by local governments.

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), China’s state planning agency, has long understood that the industry needs to consolidate. In 2007, the government established a target for the top 10 auto firms to have a combined 90% market share in 2015, up from 80% at the time. But the agency encountered stiff resistance from local officials: small automakers are part and parcel of local government budgets, as well as a major source of employment.

Moreover, attempts at forced mergers have foundered. In 2009, Guangzhou Automobile Group acquired a 29% stake in Changfeng Motor for RMB 10 billion ($162 million) at the behest of the NDRC and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), another regulator. The acquisition failed so completely that the company was eventually split into three, leaving the market even more fragmented than before.

Tougher competition and slower growth may finally do what regulators could not. “The pain threshold is going to get higher and higher for this long tail of smaller brands,” says Jullens. But when consolidation does come, it will be a net positive development for the industry. “It’s [a] process that will have to happen at some point,” he says.

Wheeling and Dealing

Foreign brands are better-placed than their Chinese competitors, but they too face challenges amidst the slowdown.

Among the most pressing is their relationship with local dealers, many of which are piling up inventory. The China Automobile Dealers Association (CADA), a trade group, reported that dealers had an average 1.83 months of inventory on hand at the end of 2014, a one-third increase on the year before and well above the 1.5 months of inventory analysts consider to be a “red line”.

The problem is that many global automakers set year-end sales targets for their China dealerships (Chinese brands usually own their dealers directly, as in Europe). Dealers that reach those targets qualify for bonuses, which can account for up to half their profits, according to CADA. But the widening gap between targets and the slowing economy has led to friction at some firms. BMW, Toyota and Daimler dealer associations have protested publicly against what they consider to be unreasonable sales targets.

“We will see more of that happening,” says Siebert. “We’ll see it from Audi, from Lexus and others, because the dealers are much stronger than before.”

New regulations from the Ministry of Commerce, which oversees auto sellers, have liberalized many aspects of the market, for example by allowing dealers to sell multiple brands or import vehicles without the manufacturer’s permission. This, says Siebert, has shifted the balance of power towards dealers. Those dealers are responding by holding less inventory and demanding more subsidies from manufacturers.

“If [the dealers] don’t get what they want, they get together with CADA, and CADA goes directly to Beijing, points their fingers at the [manufacturers] and says, ‘They’re not playing according to the rules,’” Siebert notes. “And in the end, they get what they want.”

In early January CADA announced that it had persuaded BMW to shell out RMB 5.1 billion ($820 million) to its China dealers as compensation for lower-than-expected sales in 2014. Volkswagen and Daimler are said to have paid RMB 2 billion and RMB 1 billion to their Audi and Mercedes dealers, respectively. CADA declined to comment for this article, and the automakers will not confirm the figures.

Figuring out how to handle the relationship with local dealers “must be the number one priority” for foreign automakers in the near future, says Siebert.

Changing Tactics

Another challenge is the changing nature of Chinese consumers. Jullens of Strategy& says the big automakers have so far taken a “hunter-gatherer” approach to the market, making money by scouting first-time Chinese car buyers.

Yet the market is now shifting from one of mostly first-time buyers to repeat purchasers. This will require a “seed-harvest” approach, in which carmakers sell vehicles at relatively low cost, then earn profit through complimentary services like lease financing, warrantees, accessories, after-sales services and trade-ins.

Car brands will need to place more emphasis on customer loyalty and master the economics of after-sales parts and services, as well as the used-car market—a different set of skills than what has worked so far.

Even the premium end of the market, currently dominated by Audi, BMW and Daimler, may be in for a shake-up as the market transitions from targeting super-rich buyers to the merely affluent. These “mainstream” buyers are more invested in the performance of the car, rather than simply prestige, says Jullens. That could provide an opening for a raft of budding new entrants, including Ford’s Lincoln brand, Nissan’s Infiniti and Toyota’s Lexus.

“You’re going to start to see a new business model emerge,” says Jullens. “The deck is being shuffled anew.”

Increasing overcapacity will make that juggling act even more difficult. Nearly all the big global players appear to be doubling down on China. Chow says the top brand by market share in China last year was likely Volkswagen, followed by Hyundai and Buick (owned by General Motors). Of these, Hyundai announced in late December it would start construction on two new production plants, and General Motors said earlier in 2014 it would invest $12 billion to boost capacity 65% by 2020.

“These are decisions that were made some time ago, when it still looked like there would be no end to China’s rise,” says Siebert of JSC Automotive. “I think when the [automakers] realize over the next few months that maybe there will be some sort of crisis, you will see some revisions of those plans.”

Finally, foreign car firms will need to meet a series of surprisingly tough fuel efficacy targets in China. Automakers must improve efficacy by 6% between 2015 and 2020 to meet the new requirements, says John Zeng, an analyst at LMC Automotive.

That will not be possible by simply tweaking existing car technology, so carmakers will have to choose from a variety of new technologies that might bridge the gap, including high-efficacy diesel engines, turbo-charged engines and new-energy designs. However, while the likes of Tesla and BYD have produced some high-priced all-electric vehicles, none of these options has yet proven commercially viable on the mass-market end.

“For the manufacturers, it’s like gambling—you don’t know which technology will win,” Zeng says. He adds that some Japanese carmakers have opted for hybrid petrol-electric models, but those designs appear to be failing in the market.

Too Big to Fail

Such concerns do have merit, but China remains one of the few sources of serious growth left in the global auto market. While the US is gaining steam, margins in the American auto market are slim. Emerging markets such as Brazil and Russia are flirting with recession, and there is no end in sight to Europe’s anemic growth. In this context, investing in a large market expected to grow 8% this year seems a reasonable bet.

Furthermore, many car companies have their eye on the long term. Auto penetration rates in China are less than a tenth that of the US and less than an eighth that of densely populated countries such as Japan, according to the World Bank, suggesting there is still plenty of room left for growth.

“In a long-term context, China still has significant growth potential,” says Larissa Braun, a Beijing-based spokesperson for Volkswagen. “We expect China to remain the motor for growth for both the global automotive industry and for the Volkswagen Group.”

Those remaining growth prospects, an entrenched position in the country and a lack of strong alternative markets all mean that China has to remain the companies’ focus.

Zhang of AutoForesight points to the example of Toyota to illustrate how China has transformed from a zippy-yet-optional emerging market into an indispensable pillar of the global auto industry.

The Japanese carmaker sold 1.03 million cars in China last year, falling short of its 1.1 million target and sparking rumors that it was considering an exit from China. But industry insiders know the notion is nearly inconceivable, no matter how much growth slows.

“Think about it: if you lose a million cars a year, is there another market that can make up for it? Can they really do another million in the US or European market? I don’t think so,” he says. “Who can afford to lose this market?”