Real estate in China has gone into a downward spiral and the slowing property market is casting a shadow over developers.

On a spring afternoon in Beijing, Zhou Fang is busy hawking apartments in a new residential complex along the city’s third-ring road. He doesn’t appear to be having much luck.

The buildings opened a couple months before and have plenty of amenities, including a community gym with a swimming pool, shops and a large underground parking ramp. While the apartments are not “luxury”, they are certainly designed to attract upper middle-class residents.

Zhou’s real estate agency does not allow him to offer discounts on these apartments even as the market slows. He says that “nearly everyone” in the area has heard of the developers offering “substantial” discounts on new properties further out in the suburbs, and now prospective buyers have been asking him for price cuts too.

Such discounts, which began in Hangzhou and Changzhou earlier this year, are just one sign of trouble brewing in China’s property sector. These were brought to the fore in March, when reports surfaced that developer Zhejiang Xingrun Real Estate was poised to default with around RMB 3.5 billion ($560 million) in debt. (For a detailed interview on the issues facing China’s real estate sector, click here.)

While Xingrun is not large enough to seriously disrupt the market, it has highlighted the dangers that developers face as property prices cool. Both Chinese and foreign media have warned of an impending wave of developer defaults this year.

In reality, the outlook is mixed. Smaller developers are more exposed to market swings than their larger rivals, and are facing ever-tighter liquidity conditions. A period of accelerated consolidation seems likely—though just what shape it takes will depends on how both developers and policymakers respond.

“You see the results of the Chinese developers listed in Hong Kong, and they tend to be doing pretty well. But at the same time, you’ve got smaller developers defaulting on bonds or cutting prices,” says Sam Crispin, a longtime China property analyst based in Shanghai. “That suggests there’s a real issue here.”

Where’d the buyers go?

China has almost 90,000 registered developers, according to the latest data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) released in 2012. But this year the National Australia Bank released a report in March putting the number of developers at approximately 60,000, and even among these the overwhelming majority are small companies. China’s 10 biggest developers—including firms such as China Vanke, Dalian Wanda, Poly Real Estate, Greenland, and China Overseas Land and Investment—made up just 13.3% of total property sales last year and 8.4% of floor space sold, according to China Real Estate Information Corporation.

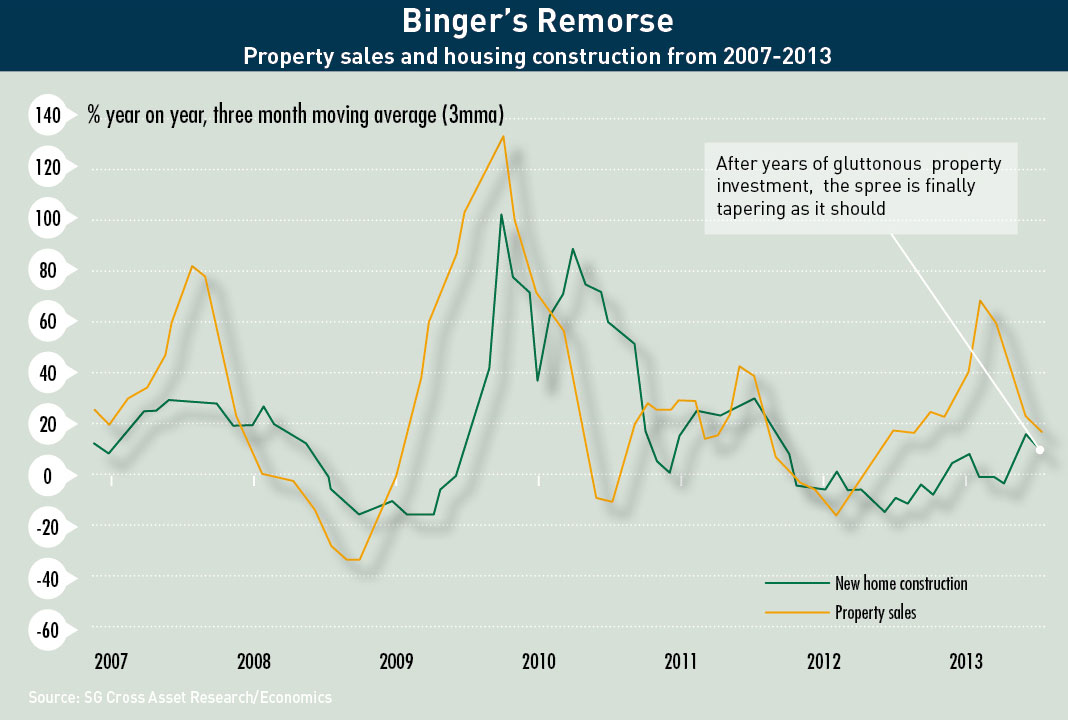

Smaller developers were at the heart of the homebuilding boom from 2008 to 2011, when Beijing and local governments launched a series of stimulus measures designed to combat the global economic slowdown. Since the boom began, home prices have regularly risen at double-digit rates, far outpacing GDP growth.

In an effort to restrain prices, the central government has implemented increasingly tough home-buying restrictions, especially in first-tier cities. These rules include higher down payment requirements, limits on the total number of home purchases, stiffer mortgage rates and so forth.

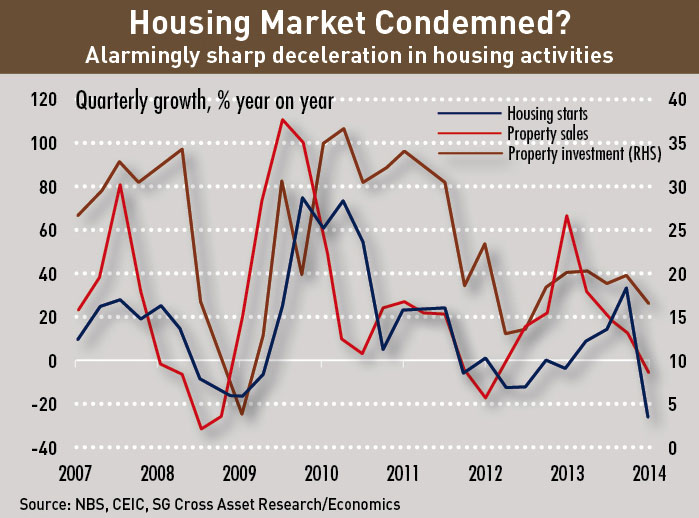

While these measures initially did not seem to have much impact, home price growth has cooled noticeably in recent months. Prices rose by 7.7% in March, down from 8.7% in February and 9.6% in January, according to the NBS. The volume of residential floor space sold fell by 5.7% in the first quarter, and the value of homes sold declined 7.7%.

“The question is: where have all the buyers gone?” says Crispin. “Because there’s seemingly not as many buyers out there in some places as there used to be.”

Touching the Peak

Developers have taken note of slowing demand: new construction fell by 25% in the first quarter, according to the NBS.

At least part of this downturn is structural. Home completions decreased by 0.5% last year, the first decline since 1995. The fall marks a turning point and suggests that “China has permanently passed the peak rate of annual completions,” argued Rosealea Yao, a property analyst at GaveKal Dragonomics, in a note to investors.

So analysts are now focusing on overbuilding in lower-tier cities. Around 67% of residential construction was in smaller cities last year, according to Nomura.

“There’s real concern about the sustainability of some of the lower-tier cities,” says James Macdonald, Head of China Research at Savills. “There seems to be a short-term, and possibly a mid-term, disconnect between supply and demand.”

According to NBS figures, prices in second- and third-tier cities have been growing much more slowly than in first-tier cities. But the problem may be even more acute because many smaller cities are not covered by official data.

By using proxies such as steel and cement consumption, Yao and her colleagues found that homebuilding in 218 prefecture-level cities grew much faster than larger cities, especially in the years after 2008. Moreover, they found that while urbanization drew around 12 million people per year to these smaller cities between 2000 and 2008, that figure has since slowed to around 4 million. Migrants are moving to first-tier cities instead, despite the overcrowding in those places.

The upshot is that homebuilding in lower-tier cities accelerated even as population growth slowed, suggesting potential overbuilding. This is cause for concern for small developers in particular, because many—such as Xingrun—concentrate on a single region or city.

They also face eye-watering financing rates. Small developers pay around 20% interest on bank loans, compared to 6-9% for big developers, according to Standard & Poor’s. Shadow bank lending rates are about 15-20%. Even a modest price slowdown could push developers into default.

Moreover, tighter credit conditions are unlikely to ease soon. Franco Leung, a Hong Kong-based property analyst at Moody’s, says he is seeing Chinese banks become much more selective. Many now have lists of “preferred” borrowers that include big developers.

“What it means is that the lending criteria to those [firms with] weaker credit will become more difficult,” he says.

By contrast, large developers are generally well-placed to ride out a slowdown. They are more diversified than their smaller competitors, and are widely seen as more prudent when it comes to buying land and designing new developments. Furthermore, large developers have much better access to liquidity should a crunch arise this year, says Leung. They can tap Chinese bank loans, as well as capital markets both in China and abroad. Several also have large stocks of housing inventory scheduled to go on the market, which should further line their coffers.

Divided We Stand

In theory, the combination of robust large developers and struggling smaller players should lead to M&A deals and consolidation. But the picture is complicated because developers have been getting smarter in terms of their management and structure.

“I’ve noticed over the years a number of Chinese developers really evolving and starting to structure their businesses in a way that helps them deal with financial downturns or downturns in the real estate market,” says James Shepherd, Head of Research for Greater China at Cushman and Wakefield. “These developers are much better than they ever were in the past.”

He notes that developers used to own a number of project sites under one holding company, now many have restructured their businesses to create a development company for each piece of land they own.

This structure makes sense due to Chinese regulations designed to discourage “land banking”, or the practice of developers snapping up available land, only to sit and wait for prices to appreciate before selling it to another buyer. Government rules thus require developers to start construction on their land holdings within a year, which stops them from “flipping” properties, making individual plots hard to sell.

However, by creating a subsidiary company for each piece of land, developers can skirt the rules by selling the firm owning the land, rather than the land itself. In theory, local governments could still intervene to curtail these transactions. But Shepherd says during tough times they tend to turn a blind eye to the practice.

This structure also solves another problem: reluctance of big developers to acquire smallers rival and assume all projects.

“In the past it was very difficult to sell a small- to medium-sized developer [with] different locations, because you’d be getting a mixed bag of sites,” says Shepherd. “China’s a huge place, and they have logistics infrastructure and a workforce ready to work only in certain locations.”

For that reason, classic M&A deals are not likely going forward, says Shepherd. Consolidation will be silent and out of public view as big developers snap up individual projects from shrinking competitors.

Falling in Line

That type of consolidation is exactly what policymakers in Beijing are hoping to see, says Macdonald of Savills. A property industry with fewer players might be easier to regulate and optimize.

To that end, by allowing Xingrun to effectively default, officials sent a “shot across the bow of the real estate and financial markets,” says Macdonald. “They said: ‘Look, we will not backstop everything’.”

Yet the government is not to be underestimated in the property industry’s outlook, not least because local officials are loath to see slowdown and consolidation. Property construction provides a big source of employment, and land sales generate about 55% of revenues for local governments. Local officials are protecting their turfs by pushing against central government property restrictions where market have slowed.

“The central government isn’t necessarily going to loosen restrictions on the property market, but some of the local authorities may,” says Macdonald. He adds that many of the looser restrictions will be in lower-tier cities, where the disconnect between supply and demand is most severe and where prices have sagged.

Regulators in Beijing have so far not pushed back against local officials who are softening the rules, resulting in a de facto loosening of restrictions in certain cities. “It’s not something that’s been shouted from the top of the roofs in Beijing, but it’s something that is being allowed at the moment,” says Macdonald.

Yet the government’s heft can be felt in other ways as well. In April, for instance, a leaked recording of remarks made by Mao Daqing, Vice Chairman of China Vanke, suggested that the government’s anti-corruption campaign was seriously impacting property demand. (The company says the recording was taken out of context.)

Many developers are keeping an eye on the planned national property registration system in particular. The platform, which will allow authorities to track the home purchases of any individual and their family members, is due to be in place by 2018.

“It’s a very powerful tool,” says Crispin. In theory, it could allow watchdogs to sniff out when an official or wealthy individual owns a piece of property far more valuable than what their official salary could afford.

Yet similar systems are already in place, suggesting the announcement is more about signaling to property owners to clean up their act. “This must be a warning,” says Crispin. “‘You’ve got three or four years before this system is in place—so do something about it.’” Crispin thinks the effect will be softer prices in the market for the next three to five years.

If that scenario does play out, it is likely to accelerate the trend among developers to focus more on mass-market homes—small and mid-sized homes aimed at middle-class consumers. These projects are less profitable than the luxury condos, says Leung of Moody’s. But developers have already been increasing their proportion because the luxury market is faltering.

In any case, developers will probably continue to focus on mass-market homes because Beijing wants them to, argues Crispin. If they wish to avoid Xingrun’s fate, falling into line with government policy may prove equally important.

“I think there’s a realization from developers that if they are aligned with government policy, then they will get more support from the state, including state-owned banks, land auctions, and so on,” says Crispin. “And if they don’t, then sorry, it’s bye-bye.”