China’s latest vaccine scandal is the latest in a long series of fake and substandard drug scandals. Has the public lost all confidence in drugs made in China?

After a stream of scandals and medical incidents, the Chinese public appears to be losing faith in drugs made in China. What are the implications for domestic and international pharmaceutical companies?

In January 2019, thousands of protesters marched the streets of Jinhu County, in China’s eastern Jiangsu Province, to voice outrage about something that has become all too familiar: another vaccine scandal.

According to the local government report, “only 145” children between the ages of three months and four years had been given expired oral polio vaccines under the state inoculation program. The news broke when one mother wrote online that her child’s dose was three weeks out of date, which was quickly corroborated by other nearby parents.

This time, the protests got ugly. A viral video of the county Communist Party head being mobbed to calls of “Beat him! Beat him!” seemed to capture the fury of the parents. The scandal sparked a nationwide probe and 17 officials were punished for their negligence.

Just months earlier, the country was rocked by news of a much larger incident involving over half a million doses of substandard vaccines for rabies, diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough. The ensuing investigation revealed that the pharmaceutical firm responsible, Changchun Changsheng, had falsified its production data to hide the fact it was using expired ingredients and illegal production procedures in order to cut costs.

“This vaccine case has broken the moral bottom line,” said Premier Li Keqiang before opening the inquiry. Changchun was fined RMB 3.4 billion ($510 million) and stripped of all pharmaceutical licenses.

“The main impact of the string of scandals has been to pressure the leadership into recognizing the sensitivity of quality healthcare as a political issue,” said George Baeder, senior vice president at clinical contract research firm dMed Global in Shanghai. “It’s clear now that this can no longer be ignored or dealt with in an ad hoc crisis manner.”

The challenge before the government is clear: restore confidence in the system or risk jeopardizing the growth of China’s $130 billion healthcare industry.

Trust Deficit

When a company makes a PR fumble, such as Samsung’s infamous exploding phone of 2017, it can cost millions of dollars to resolve their tainted image. The incident caused Samsung’s global market share in premium phones sales to plummet from 35% to just 17%. Similar blunders can cause companies to close the door on a large chunk of business.

For China, the scale of the challenge is enormous. The government has to convince the world’s most populous nation that it is willing and able to overhaul the entire health regulatory infrastructure. This means re-examining all parts of the domestic healthcare machine, from supply chains and research to imports and hospitals.

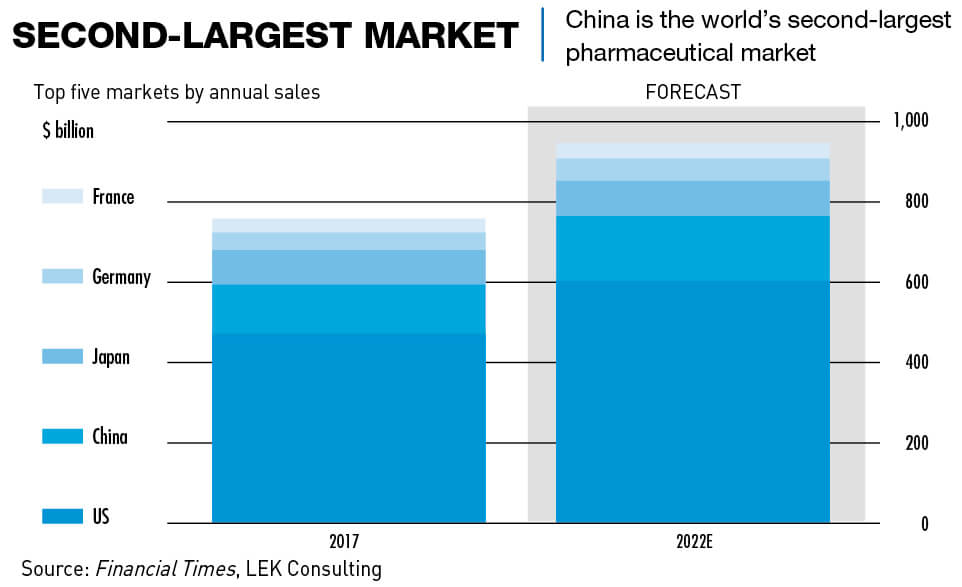

China’s pharma market was worth $123 billion in 2017, according to consultancy L. E. K., making it the world’s second largest by sales behind the United States. This is expected to jump to $160 billion in the next five years as the Chinese population ages and gets wealthier, aided by a steep increase in nationwide R&D spending as part of Beijing’s “Made in China 2025” industrial development policy.

China is also emerging as a powerful exporter of pharmaceutical ingredients to other markets, especially the US. Besides traditional plant-based products, domestic manufacturers are stepping up their production of generic drugs—those for which original patents have expired, such as paracetamol—to sell overseas, connecting China with the global pharma market and its standards.

But so far, a combination of size, corruption, and cultural attitudes toward healthcare have long dragged down regulatory standards for end products, scarring the reputation of Chinese goods among patients and consumers.

China is still getting to grips with how to effectively marry regulation with what was for decades an industry in which production was entirely state-controlled. The first central regulatory body, and all accompanying legislation, was set up only in 1998, just over 20 years ago.

“The previous government manufacturer, the State Pharmaceutical Administration, was concerned with output rather than quality,” said George Baeder. “It had limited control over individual plants which were under the influence of provincial governments.”

Since then, an explosion of pharmaceutical oversight departments has often led to clumsy delegation of responsibilities. Before the landmark government reshuffle in spring of last year, the lack of clarity on the remits of the National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC), the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA), the General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine (GAQSIQ), and the Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) inevitably created regulatory loopholes for players in the giant sector. With an estimated 6,000 pharma manufacturing sites throughout the country, the auditing requirements are staggering.

China has one of the most under-resourced healthcare systems in the world, both on the regulatory side and in terms of medical provision. In 2017, the CFDA reported around 300 internal reviewers, while the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had an estimated 2,000. There have also been reports of high-level corruption in the past, typified by the execution of former chief of the State Food & Drug Administration (SFDA) in 2007, for accepting $850,000 in kickbacks.

Despite steady annual increases in expenditure, the total healthcare spend in China only amounts to 3% of the world total and that is to look after 22% of the global population, according to China CITIC data. Similar to Canada, almost the entire Chinese population is covered by state-run health insurance. But since the coverage doesn’t extend to many essential services, people still have to pay a large share of medical expenses from their own pockets.

An explosive account by the Chief Executive of iKang Guobin Healthcare Group late last year shone the light on how this may have allowed scandalous behaviour to creep into China’s $10 billion medical examination industry. Speaking at the Chinese Enterprise Leaders Summit, Zhang Ligang reported that nurses were posing as doctors to draw blood for a screening, and then fabricating results to avoid doing the work.

“Trust really is the underlying problem,” said Dr. Scott Wheelwright, founder and principal consultant of Complya Asia. “In many respects, China has an even closer eye on its drug market than other countries, but this is an industry-wide problem, particularly for economies at an earlier stage of development.”

This endless stream of drug and medical scandals has eroded Chinese public trust to the extent that many patients now look elsewhere for healthcare-related products, placing greater faith in the systems of Australia, Hong Kong, or Japan.

“I always ask my friends or relatives to bring back huge bags of tablets and syrups when they go on holiday, and if we need it, more important medicines,” said Zhi Juan, a former health sector worker and mother of two. “Chinese companies just want money, I know it. And the government is involved, too.”

Restoring Confidence

Despite the ongoing stream of scandalous headlines, there are signs to suggest that China is working hard to right the situation and not just react to problems as they arise but take a more structured approach.

The goal of significantly improving the regulation of medical products was included in the latest five-year plan (2016-2020) which stated that China will by revise, or formulate, around 3,050 national drug standards and 500 medical device standards during the period. Two years later, the CFDA compounded these goals by publishing the pivotal “Guidance of Further Strengthening Food and Drug Standard Work,” which has since led to a series of national drug standards being drafted.

Streamlining has also helped to address the redundancy of functions among regulatory bodies. The National Medical Products Administration (NMPA), the successor to the SFDA, was elevated to ministerial-level status in 2013, after already taking on greater duties five years earlier in the wake of the nationwide dairy product crisis. Following the 2018 government reshuffle, the administration now only supervises the safety of drugs, medical devices and cosmetics.

“In 2018 China underwent significant institutional reform,” said Yilia Ye, senior editor at regulatory consultancy ChemLinked. “The administrative optimization of establishing an office exclusively for drug oversight will certainly lead to a more stringent supervision of pharma safety.”

China’s increasing engagement with the global healthcare market, both as an exporter and as an importer, has also been a driving force behind regulatory reform. Plagued with approval waiting times of up to 40 months for new drugs and a chronic shortage of high-quality generics the issue even became a box office hit last summer with the film “Dying to Survive” highlighting how difficult it is to get certain drugs in China already approved elsewhere in the world. China has invested billions of dollars in new staffing and rolled out new rules to cut the backlog of imported drugs waiting for the green light.

At the end of 2017, there were over 800 reviewers employed processing applications, with more hiring planned for 2018, however, approval times have since more than halved, from an average of 18.5 months in 2016 to just 8.6 months in 2017. In December, Astrazeneca’s roxadustat became the first foreign-made drug to gain approval in China before doing so in the US.

In June, China was admitted to the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, requiring Beijing’s central pharma watchdog to adhere to the council’s safety guidelines. As of 2017, overseas manufacturers no longer have to repeat clinical trials within China before getting drugs to market.

“As ICH guidelines become China’s standard, China is increasingly willing to accept global clinical data in support of local product registrations, with priority for products that serve Chinese patients’ unmet medical needs,” said Lingshi Tan, director of the Drug Information Association in the US.

“Staffing the NMPA will take a decade to create the talent pool to act as regulators or to provide the right quality systems within pharma manufacturing operations,” says George Baeder. “Training people who really know how to create and implement ‘good manufacturing practice’ systems within companies is no quick fix.”

Wider Implications

The stakes are high for the Chinese authorities to get their act together. Not only is biopharma a priority industry for Beijing’s development goals, but with public trust damaged, there is the risk of a large-scale consumer backlash.

Over 50,000 children were affected by the widespread use of melamine—a resin—to falsify nutrient contents in infant milk formula. The public perception of domestic brands plummeted, creating a demand for trustworthy products which foreign firms were able to take advantage of and soak up market share. The scandal had such a deep impact that many parents today still think of it when choosing their children’s food.

“I didn’t have children in 2008, but I remember my friends and older relatives getting very frustrated and concerned about the news,” said Yi Hua, a young mother in Shanghai. “Now I have my own child, and because I can afford it, I basically only buy imported goods of this kind. Why risk it going Chinese?”

Foreign drugs bear a similar stamp of approval. China’s daigou market, for example, in which armies of (usually) young women travel abroad to buy coveted foreign-brand products and then sell them back home via social media, may be worth up to RMB 50 billion ($7.6 billion), according to Bain Capital estimates. Many more travel out of China every year to places like the US and South Korea as ‘health tourists.’

Chronic suspicion of China’s pharma industry is a huge burden for domestic firms, but they have been making progress in establishing themselves both at home and on the world stage, particularly those in the private sector. According to Dr. Scott Wheelwright, China’s homegrown firms are quickly realizing that “winners don’t cheat.”

“Businesses, and indeed the government, are recognizing the threat that this bad reputation will have on the Chinese market,” said Wheelwright. “In the US, for example, which had its own string of issues 25 years ago, honesty and professionalism has replaced tighter government control because CEOs know they’ll lose clients if they don’t provide a reliable service.”

China’s blossoming drug export industry is already testing the capacity of foreign oversight committees, such as the FDA in Washington, to effectively review all the Chinese ingredients entering its ports. The Financial Times has reported that somewhere around 40% of US drugs contain Chinese-made ingredients, meaning any slip in confidence could force customers to other suppliers vying for business, such as India.

For the multinationals, however, their enthusiasm has yet to be dampened. Foreign drug makers still make up the top five largest companies in China by market share, and they appear to remain bullish on China as a source of future growth, given that it still doesn’t account for a large portion of existing sales.

“They’re investing in ways that they haven’t before,” said Wheelwright. “Firms like Eli Lilly and Pfizer, for example, are now producing drug substance [the active pharmaceutical ingredient] in China, not just drug product [the finished good such as a tablet or syrup], which shows that they’re taking the market more seriously.”

And rightly so. China has already made it clear that it aspires to become a global pharmaceutical powerhouse, both as a consumer base and innovation hub. But before it prepares to conquer overseas markets, China must first convince its own citizens that its drugs are safe.