China is a long way from football dominance despite a clear focus on the sport’s development. Why is that so?

The ball sailed past China’s powerless goalkeeper to give Japan a 1-0 win in mid-September, pushing China’s men’s football down to the bottom of their group in the World Cup qualifying round. It was yet another ignominious step in China’s so far failed long march to global football supremacy.

The view from the bottom of the group is not the one China’s leader Xi Jinping envisioned when, in 2015, he made the ambitious statement that the country must become a major footballing power by 2050. This aspiration was bolstered by the introduction of a reform plan that aimed at a wide-reaching, top to bottom, revitalization of Chinese football.

Goals were set for drastically increasing the quality and uptake of youth football, widening the availability of footballing spaces and the continued development of large-scale infrastructure, and a significant increase in quality of China’s performances on the football field.

There has been progress in some areas since, but it is clear that there are a significant number of hurdles to football development in China. With several corruption scandals in its league’s recent history, continued poor performances by the national team, inconsistent support from governments and businesses and, most importantly, a lack of youth involvement, Chinese football still has a mountain to climb.

“Absolutely China can do it, but it will not be easy, it requires patience, it requires a resolve and it requires strategy,” says Simon Chadwick, Global Professor of Eurasian Sport at France’s Emlyon Business School.

Lofty goals

In 2015 the government introduced the Overall Chinese Football Reform and Development Plan, setting out a series of short-, medium- and long-term goals to redefine the football landscape in the country.

In the short-term, it called for an improvement of the general environment around football development, medium-term, a significant boost to youth football and more success for Chinese teams in international competition, and long-term simply global football domination and the deep embedding of football in the national culture—the best players in the world, the best national team in the world.

“It’s very ambitious, but this is important and there has to be a long-term approach,” says Mark Dreyer, founder of China Sports Insider, a sports business news and analysis website. “It takes a minimum of 20 years to turn things around because you have to start with five-year-olds and they obviously can’t produce international results at that age.”

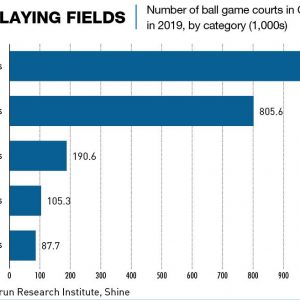

The Plan also provided detailed instructions for upgrading the Chinese Football Association (CFA), developing campus football and increasing the popularity of social football. The newly created National Youth Campus Football Leading Group Office set a target of 85,000 on-campus football fields by 2020 and 50,000 football-featured schools—a school where football education makes up part of the curriculum—by 2025. The country built over 26,000 new football pitches between 2016 and 2020 for a current total of 105,300 across the country, compared to only around 6,000 new pitches constructed in the previous five years.

The Plan also called for a more grassroots approach to the cultivation of young talent, moving away from the previously dominant ‘Soviet Model’ of taking potential stars at an early age and attempting to develop them through rigorous but somewhat siloed training. The sports and education ministries have been tasked with supplying policy research and improving campus football, but most of the youth development is being done by a series of smaller, independent grassroots clubs alongside a network of schemes run by international footballing giants such as AC Milan and Manchester City.

But there is no exact budget attached to the goals and it is mostly up to harried local governments to increase spending, alongside financial input from the Chinese lottery and private investors.

“I think we can say the first parts of the plan have been put into place, but it will take a little bit of time and organization to get it all moving in the right direction,” says Mark Thomas, Managing Director of S2M Consulting, a China-focused sports events company.

At the top of China’s football hierarchy are the national teams, while at the bottom are social football clubs, which are slowly expanding, but the most visible manifestation of football in China is the Chinese Super League (CSL), composed of 16 teams from which most of China’s players emerge. Many of the teams are owned by Chinese private corporations. Seven new major stadiums associated with CSL teams are slated to open in the next two years across the country

“The owners don’t really care whether the club will make money,” says Lingling Liu, Managing Director of China Sports Business Consulting. “For them, it’s just another name on the business card. Their purpose is not making this football team profitable or successful. Their purpose is to use it to get resources from the government.”

The footballing landscape

Established in 1994, the Chinese Super League runs from February to November, which is at odds with the traditional Autumn to Spring football season in the West. The league has overall revenues of $1.12 billion per year, only around 15% of the equivalent number for the English Premier League, the largest league in the world by value.

For most top leagues around the world, the main income sources are ticket sales, promotional sponsorships and broadcast rights. In each case China’s football league is not in good shape. The league games are mostly well attended, but ticket prices are cheap and many of the promotional sponsorship deals are league-wide with the income being divided equally between all teams, whereas the major football leagues hand out the money based on league placing. China Sports Media (CSM), the leading sports broadcaster in China, bought the broadcasting rights to the league in a five-year deal in 2016 and has since extended it for another five. The entire deal is now worth around $1.73 billion, which is about a tenth of the most recent English Premier League rights deal.

While the players in the Chinese men’s national team come from the CSL, many of the best players are imported from overseas and naturalized in the name of footballing progress. In 2019 and 2020, 11 foreign nationals were naturalized and over half of these players had no Chinese ancestry whatsoever. The women’s team has fared better in this regard, with very few players being of non-Chinese origin. But in the last six years since the implementation of the new policy, the situation with regard to both men’s and women’s football has not particularly improved. The men’s team is languishing well below 70th in the FIFA global rankings and sits eighth in Asia, while the women’s team ranks 17th in the world.

The fundamental problem for both the professional league and national teams is the dearth of quality players, and that is caused by the fact that children in China don’t tend to kick a football around after school, as they do in established footballing nations.

Falling foul

The image of two children running home from school to grab a football and take it to a neighborhood park to kick around is an easy one to conjure for people in countries where the sport is a prominent part of day-to-day life. In China, however, familial and academic pressures tend to stand in the way of such pass-times. “Most parents and grandparents want to see those kids achieve the best in terms of academia, they care little about sports,” says Mark Thomas. “Historically, the direction they have wanted to push their kids in has not been football.”

Every minute of Chinese children’s lives outside of school tends to be structured around supplementary learning in a variety of topics, led by maths, English and music. Although it seems to be becoming more popular with the growing middle-class, football has not traditionally been a part of that structure. “They think everything is important, or more important than sports,” says Lingling Liu. “You know, maths is important, English is important, music is important but sports, sports are not so important.”

This has led to the classic profile of a Chinese social football player being a mid-twenties urban man, playing 5-a-side games with his colleagues on a weeknight after work. In countries where football is more dominant, that profile is far more diverse. Xu Zehua, a 24-year-old from Lanzhou, loves playing football, but admits that that is somewhat rare in China, especially among the young. “When I was in high school, I was the only one who liked football and I had to go to the football field in my neighborhood and play with people 10 years older than me,” he says. Now he lives in Shanghai and plays as often as he can, but a lack of teammates remains a problem, and the high costs of pitch rental also limit his playing time. “I found it difficult to play football because football pitches in Shanghai are very expensive, but now I play with my current company and we have enough people to cover costs,” he added.

Reputational regrets

Football does have a certain level of popularity in the country, with around 200 million people considering themselves as fans of the sport, but this pales in comparison to the support of basketball, which has around 625 million supporters.

Basketball’s popularity in China owes a lot to the success of Yao Ming, a Chinese player who had a meteoric rise to stardom during his time playing in the NBA for the Houston Rockets during the 2000s. He became the face of the sport in China and provided millions of young children a face to idolize and moves to imitate when playing out in the street. During the height of his fame, sponsors and companies recognized the value of Yao Ming in the Chinese market and utilized him to both build basketball in China and sell related products, so much so that he topped Forbes’ Chinese celebrities list in income and popularity for six straight years up until 2009.

Football, on the other hand, has no such cult hero for Chinese children to look up to. For the few good players that emerge from the Chinese system, some stardom can be achieved in the CSL, but true hero status comes from success abroad, and Chinese players are, in almost all cases, outclassed in terms of the professional leagues elsewhere. “So the players weigh the decision: do I stay in China in the CSL where I have a bit of fame, or do I go across to Europe, where I’ll probably be playing in the second level or third level. It’s a pretty miserable existence,” says Rowan Simons, Chairman of China ClubFootball FC and author of Bamboo Goalposts. “So very few have taken that opportunity to go abroad.”

Additionally, the CSL doesn’t have the best reputation, with a multitude of problems marring its history. Corruption and match-fixing have been rife, Shanghai Shenhua, champions of the CSL’s previous iteration, the CJAL, were stripped of their 2003 title in 2013 due to match fixing. A few years prior, the ‘Black Whistle’ scandal saw six Chinese division two teams punished for match fixing by the CFA. Financial mismatches between meager team incomes and inflated salaries are also prevalent. Jiangsu F.C. were, in 2015, the fourth-wealthiest club in the CSL with a revenue of $36 million but, in January of 2016, they paid $50 million for a single player transfer. This financial mismatch has led to an unparalleled level of team instability, with Jiangsu, the current reigning champions of the CSL, unable to defend their title this year, not through lack of skill or determination, but because they simply do not exist anymore. The club folded citing financial issues before the start of the 2021 season.

“Looking at the professional football level, economic sustainability has been the key issue,” says Sascha L. Schmidt, Director of the Center for Sports and Management at the WHU-Otto Beisheim School of Management. “Nearly none of the professional football clubs have been profitable and only a handful have developed youth teams.”

There have been various reasons given for the national teams’ lackluster performances over the years: a lack of national interest; a veritable conveyor belt of inexperienced managers; and even at one point Chinese netizens tried to claim that maybe it was all just a genetic Asian thing and that they should give up. The footballing success of Japan and South Korea suggests otherwise. But, as ever with Chinese football, a lack of talent and youth development has been the key driver in the national teams disappointing history.

The lack of youth football hamstrings the Chinese game at all levels and for those children that, despite the barriers, do still choose to play football, the Chinese talent development system was also severely limited before the implementation of the Plan. The use of the so-called “Soviet Model” of talent development left the country with a scarcity of talent.

“The Soviet Model was the chosen approach, and that is why we are where we are today. The continued use of an old-fashioned, outdated, unsuccessful model, which had been abandoned by everyone,” says Rowan Simons. “It only really started to change after 2015.”

Promoting new talent

A new footballing structure is taking shape in China, but it is disjointed. The necessary solution requires a fundamental change in culture, and China has made progress in terms of “hardware”—infrastructure—but “software”—footballing understanding—still lags behind.

Exposing children to football through schools has been a major tactic of the development plan and more children are playing, simply by virtue of being part of the education system. But there is a disconnect between school-based participation and embedding football within a child’s day-to-day life.

“The campus football program is good in as much as many more kids now get exposed to football,” says Simons. “But football needs to become part of society, it has to become a culture and almost everywhere in the world that plays football, that culture is built through amateur, grassroots clubs. China has gone from no kids playing football, to a huge number of kids playing football at school, which is good. But it’s not enough, there needs to really be a link between the schools and amateur clubs.”

Alongside the increased numbers in school, there have also been some positive grassroots organizational developments. Simons’ organization, China ClubFootball, for example, is the largest independent grassroots football network in Beijing and delivers internationally-qualified coaching. It manages an 80-strong league, in which it enters 26 teams. Other teams in the league come from similar, smaller grassroots organizations such as Sports Beijing, which was set up by parents over 20 years ago and offers a wide range of sporting activities for the youth of Beijing.

“Scale is an issue,” says Simons. “There’s over 6,000 junior coaching operations in China. But most of them are very, very small and only around 10% of them are profitable. We are one of the few that makes a profit and that works with over 2,000 kids. It’s a drop in the ocean.”

Clearly, progress has been made over the last few years but encouraging China’s youth to kick a ball remains a daunting task. Without youth interest and opportunities, players end up learning basic skills, such as ball control and footwork, too late. This has the knock-on effect of them learning the macro, team-based coordination that makes football so special, far too late. Manifesting itself in China as delayed debuts and the creation of squads that are fairly unique.

“I think the lack of youth opportunities is a big problem. There are players making their debuts at the ages of 23 or 24, and that’s not considered unusual here,” says Mark Dreyer. “There are under-25 squads. Nowhere else in the world would have an under-25 squad. It’s such a weird age—that should be the first team.”

Goal?

Given the mountain of issues standing in the way of China’s footballing ambition, it is not going to be easy to reach the summit of world football, but it’s not totally out of the question.

“I think the reforms will lead to positive outcomes in the future, eventually. But football is so complicated in China and the CFA and the other groups leading the change are in a very hard position, not because they misunderstand football, but because the changes are so difficult,” says LingLing Liu.

Simon Chadwick agrees, stressing that “it is important that the football authorities in China stay on this trajectory and they don’t lose their nerve and change direction. I think there is a tendency for that in Chinese football, and to sometimes undo the work that they’re trying to do.”

Long-term, grassroots solutions have to be the answer, but is it possible to see some success now, perhaps at the 2022 World Cup? Rowan Simons is not particularly optimistic, but can’t escape the pervasive romanticism of the game. “I think if they qualified, it would be a miracle but you know, anything can happen in football.”