Zhang Xiaomeng is Associate Dean of the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, Associate Professor of Organizational Behavior, and Director of the Center for Leadership and Incentives.

She also holds a Ph.D. from the Smith School of Business at the University of Maryland. This article was originally published in the Chinese version of the Harvard Business Review in April 2019.

China’s economic development and industry-wide changes have had a huge impact on the leadership skills of Chinese corporate executives over the past 30 years

The Leadership and Incentive Research Center of the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business recently published its first study on the leadership characteristics of top-level management in Chinese enterprises. The report, Research Report on the Leadership of Top Management of Chinese Enterprises in the Transition Period, was based on evidence from 1,906 respondents collected from the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business’ EMBA and Executive Education programs. Participants came from mainland China, Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan, and consisted of leaders of private enterprises, state-owned enterprises and non-profit organizations. It is the first research of its kind to study the leadership of Chinese corporate executives.

Leadership behavior theory was used to analyze the characteristics of the leaders, dividing participants into basically two categories—task-oriented leaders and relationship-oriented leaders.

Task-oriented leaders prefer to focus on the planning, scheduling and achievement of a task, provide guidance to their employees and set high but realistic performance goals.

Relationship-oriented leaders, on the other hand, show trust and confidence in their employees, provide support for their team and ensure that employees feel valued.

“Situational leadership” is a management tool which looks at how effective leaders are, not only in prioritizing the completion of a task, but also with regards to maintaining collaborative relationships and focusing on teamwork in the process. In other words, the key to optimum leadership is finding a balance between task-orientation and relationship-orientation leadership styles.

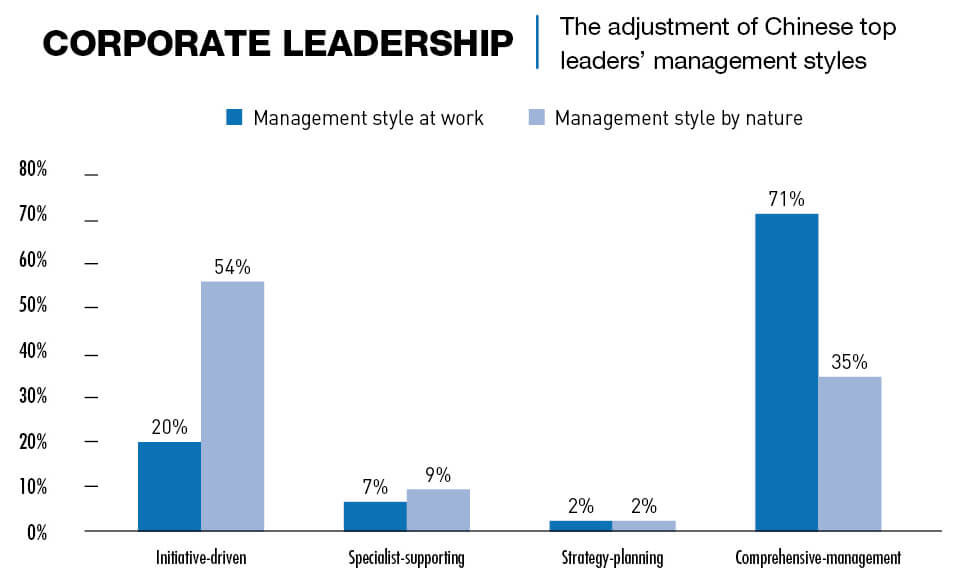

The research showed that Chinese corporate executives who grew up during the evolution of the more liberalized Chinese market tend to share some common leadership traits. Generally, they are naturally authoritarian and good at taking initiative, and tend to focus on results. As work environments have adapted over time, however, leadership styles have changed from being initiative-driven to encompassing more comprehensive management styles, which focus on the balance between ensuring the well-being of employees and achieving goals.

Personality and leadership

Generally speaking, when an employee joins a company, their social personality is typically already set, meaning that few qualitative changes are likely to occur.

Personality types and management styles are different from leadership styles although there is some overlap.

More than half of the entrepreneurs in the research project (52%) were calculated to have an “authoritarian” personality, with another 10% having a “social” personality, 6% “patient” and 12% “logical.” The remaining 21% were “flexible,” usually shifting into one of the four depending on the situation they are faced with.

It was also discovered that the authoritarian management style is directly related to one’s hierarchy in a company. The higher the position, the higher the proportion of “authoritarian” managers.

Industries with the highest proportion of authoritarian managers were manufacturing and IT, both of which tend to feature fierce competition. The competitive disposition of these industries requires better decision-making and execution skills. In addition, the market structures of these two sectors can change rapidly, and the personalities of managers in these two industries tend to be more distinctive.

Although traditional Chinese culture is authoritarian in nature, statistics have shown that the five management personality types are more or less evenly distributed in society. But when it comes to the top leaders of a company, the proportion of authoritarian managers becomes abnormally high. This is seen in the more senior managers and is the result of the often highly-selective career ladder that they need to climb.

Enterprises allocate resources according to the market. An excessive proportion of authoritarian managers therefore results from the long-term cultivation of successful managers in the market environment. Enterprises that effectively discover, nurture and utilize managers with authoritarian personalities are often more likely to survive.

Changes in China’s management style align with the period of “reform and opening up,” when China started to open up more to the rest of the world and liberalize its markets, officially starting in 1978. However, real urban reform began in 1984, and it was not until 1992 that the market economy was formally established, which gave birth to the famous “Generation 92 entrepreneurs.” Thirty years on, most of these entrepreneurs are still working.

The relatively singular personality of Chinese entrepreneurs reflects the relatively singular market environment of China over the past three decades. Planned economic development emphasized the accumulation of light consumption, and the reforms released huge amounts of pent-up demand, resulting in a number of periods of concentrated consumer consumption. The subsequent invention of the internet and resulting change in consumption patterns required companies to quickly launch products to fill market gaps and distribute goods through competitive pricing. The results-oriented business models involved created a generation of authoritarian managers.

However, we also observe that managers are changing their leadership styles. A total of 63% of corporate executives tend to prefer other leadership styles over an authoritarian leadership style. Their attitudes are no longer “only me alone,” but focus on strengthening communication with others.

This is also supported by a breakdown of the data. The proportion of executives in various industries showing weakening authoritarian leadership behaviors exceeded those exhibiting intensified authoritarian behaviors. The highest reversal was in manufacturing, reaching 72%, and the authoritarian reversal of top leaders of enterprises is as high as 71%. Now, the management style of corporate executives mainly fall under the categories of initiative-driven (54%) and comprehensive management (35%).

The influence of economic environments

But how deep an understanding is there of this change in management effectiveness and how sustainable is it? As we know, there have been uncertainties recently in the political and economic climate both in China and abroad. When the dust settles, will the leadership style return to what it once was, or will it evolve further? For a number of reasons, we believe that the latter will be the case.

First of all, our research sample was made up of executives who have studied at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. We found top executives do not necessarily have to deal with all of a company’s challenges. Mature enterprises generally have a team of flexible middle-level managers who provide a buffer for the highest decision-makers and handle most of a company’s short-term fluctuations, allowing executives to focus on the most important task of determining overall strategy. Statistics indicate that changes of approach often first penetrate the middle level managers of many enterprises and are then transmitted to the highest decision-making level. This has a strategic significance.

Secondly, in comparing task-oriented and relationship-oriented leaders, the goal of the task-oriented leader is to achieve information symmetry, a full understanding of the business from decision-making to the final output. In contrast, the relationship-oriented leaders always maintain information asymmetry. Lower-level employees usually know more about what is happening on the ground and it is therefore necessary to pay attention to the balance between the well-being of people and objectives, to stimulate initiative and creativity, and empower employees working at the grassroots level.

The two leadership styles target different micro-contexts differently and also have their own prominent professional characteristics. The current transformation of Chinese enterprises and industry sectors has revealed some important trends. China’s “economic miracle” is mainly attributed to the manufacturing industry, but in the past 30 years, all sectors have been working hard to solve the problems of scarcity.

Today, all industries are becoming saturated, with growth through meeting unmet market demand increasingly difficult. China’s economy is seeking transformation in two fundamental areas: high-tech research and development in the business area, and creativity and services for consumer facing businesses. The organization and leadership required for these emerging businesses are very different from traditional manufacturing.

James Q. Wilson, a renowned American contemporary political scientist and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, developed a public management model which is also applicable to enterprise management. It divides an organization’s output and results into four quadrants according to observational difficulty. When output and results are visible, it is called “production organization,” when the output is visible and results invisible, it is called “procedural organization,” when the output is invisible and results visible, it is called “process organization,” and when both output and results are invisible, it is called “solution organization.”

Traditional manufacturing is a production-oriented industry, and its output and results are easy to observe. The large-scale manufacturing model pioneered by the famous Ford car assembly lines of the 1920s enabled precise control by breaking down the process into simple repeated actions. The development of information technology in the past 40 years has provided a more complete toolbox for such control. But emerging businesses do not have such two-way transparency.

In the service and experience economy, companies can only control the easy-to-measure parts of employee output, just like traditional manufacturing. For example, the catering industry can control the speed of meals, but it is difficult to quantify the “critical moment of contact with customers.” As a result, customer satisfaction is difficult to observe and quantify. There are huge uncertainties in creative and R&D operations, making output and results difficult to observe.

In short, traditional manufacturing is inclined toward task-oriented management, and new businesses require a strengthening of the proportion of relationship-oriented managers, so as to make the two more balanced. Reflecting on the changing situation, the leadership style has been greatly adjusted from being initiative-led to being more based on comprehensive management.

Finally, China’s development has been mainly compared against the United States, the pioneer of the market economy. The mature business environment in the US contains a variety of situations, and the natural personality and management style of the corresponding managers are also very different. In contrast, Chinese entrepreneurs overall have a single management style. This singleness is clearly a product of the primary stage of the market economy, and is expected to diversify with economic development. Looking back at the history of management, in the early days of American development, the US also experienced a stage of authoritarian managers.

According to Stephen Barry, professor of organizational theory at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Gideon Kunda, professor in the Department of Labor Studies at Tel Aviv University, research on the history of management shows that for a century, “rationalism” and “humanism” alternated as the main style of management every 20 to 30 years. This is consistent with the macroeconomic cycle. Rationalism attaches importance to capital management, while humanism attaches importance to labor management, which can be considered as task-oriented and relationship-oriented, respectively. The Chinese economy has clearly been dominated by rationalism for the past 30 years, and now it is time for an adjustment.

In summary, the long-term trend will be for top Chinese managers to strengthen relationship orientation, and downplay task orientation. Thus, the adjustment of individual managers is far from sufficient, and enterprises need to deal with the managerial class as a whole.

Enterprises should steadily promote transformation according to their own circumstances. Companies that are still in their early stages of development, as well as industries that have not yet achieved industrial concentration, still need to rely on authoritarian managers. As the market matures, referring to the above analysis, the emphasis moves to adjust the evaluation system of enterprises.

In the past, it matched the single business model, and the short-term performance appraisal was fair in form, but was actually more conducive to authoritarian managers, not conducive to other management styles, especially strategic. In the future, depending on a company’s situation, a longer-term incentive system will have to be adopted.

In the past, adopting a single business model ensured a smooth performance appraisal, but in fact it was more conducive to authoritarian managers, and not conducive to other management styles, especially strategic ones. In the future, we should take a more effective incentive system to provide a longer-term perspective.

Long-term incentives are not limited to traditional Key Performance Indicator areas, including extending the assessment cycle and introducing more indicators, but also to establishing a benefit-sharing mechanism, including the granting of equity and options. Insufficient incentives are the core problem of many enterprises’ weak transformations. Failure to establish a sharing mechanism can be attributed to both subjective factors, such as extensive growth methods and a lack of room for adjustment of interests.

This study revealed the relationship between macroeconomic transformation and micro-level situational leadership. It also found that change is the spirit of situational leadership theory.