John Lennon and Paul McCartney wrote almost 180 songs together between 1962 and 1969, most of them recorded by the Beatles. One of them, ‘Yesterday’, has been recorded by more artists than any other song according to the Guinness Book of World Records. Imagine if Lennon was given full credit for all of those songs and McCartney none. If the music industry and fans followed the same practice as most public universities in China, then that’s the way it would be.

Except for a brief period in early 1962 when three songs were credited as “McCartney-Lennon” (See footnote 1), all of the songwriting duo’s joint collaborations were credited as “Lennon-McCartney”. Under guidelines established by the Ministry of Education, the standard practice at most Chinese public universities would give McCartney credit for the three songs and Lennon credit for all the rest. That’s because they give credit only to the first author of any article written by faculty when determining their annual bonuses and promotions (See footnote 2). The rule applies to any number of authors. So under the universities’ policies George Harrison would get all the credit for the Beatle’s performances.

Economists believe that people respond to incentives. This is useful because incentives can be used to steer behavior toward desired outcomes. But it also means that they have to be applied carefully. For example, if an auto dealership bases a salesperson’s salary on the number of cars sold in a month, we expect the salesperson to work hard at selling as many as possible. This means that they may lower the price too much in order to move cars thereby lowering the dealership’s profits. If the dealership instead rewards the salesperson based on their total profits from sales, then the salesperson will balance quantity sold with price obtained.

If we apply this same analysis to the university’s incentive scheme, we find that it creates perverse incentives. Most importantly, it discourages research collaboration between academics. If two professors are thinking of working together they must decide whose name will appear first. Since only one can do so, the other has no incentive to cooperate. If two faculty work on many papers together over time a possible solution is to alternate the name ordering: Professor A is listed first on the first paper, Professor B first on the second paper, Professor A first on the third paper, and so on. This works (and I have talked to people who have implemented this workaround) but many academic ideas are serendipitous and the practice of crediting only the first author discourages these one-off ideas from being produced.

The perverse effect on behavior may go one step further. Knowing that collaboration will not come to fruition, professors may not bother to discuss ideas. Why invest time in such discussions if the payoff is unlikely to be realized? This is a pure loss for society as some of the greatest ideas are jointly created. The idea of prospect theory, one of the ideas for which Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in 2002, was jointly created by him and Arnos Tversky (See footnote 3).

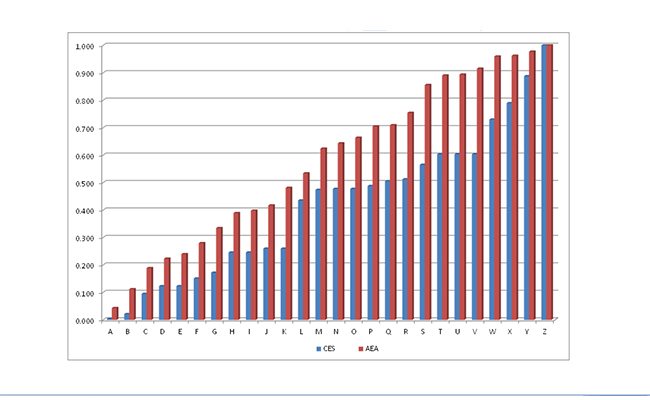

This incentive scheme also likely places Chinese academics at a disadvantage when they publish with foreign academics. Within the field of economics, a common practice if co-authors put in more or less equal work is to order the authors’ names alphabetically. Given the preponderance of Chinese surnames beginning with “W,” “X,” “Y,” and “Z” Chinese academics are much more likely to be listed last on a paper. These effects can be seen in the figure below. There I compare the first letter of the surnames of a sample of economists of Chinese ethnicity to those of a population of economists from all ethnicities. The former includes all economists of Chinese ethnicity who belong to the Chinese Economist Society (CES) (See footnote 4). The other is all attendees at the annual American Economic Association (AEA) held this past January in San Diego, California (See footnote 5). These are economists of all ethnicities (including Chinese) and should fairly represent economists working in North America which is the primary locus of academic economics.

How do we interpret the figure? Each bar in the figure represents the fraction of surnames in that sample (blue for CES and red for AEA) that have a surname beginning with that letter or alphabetically earlier. For example, about 4% of the surnames at the AEA began with “A” while virtually none at the CES did so. The bars for “B” give the fraction of surnames in each sample that began with “B” or “A” – about 2% for the CES sample and 11% for the AEA sample. The bars for “C” show the fraction of surnames beginning with “A”, “B” or “C” and so on. The key thing to note in the figure is that the CES bars are always below those for the AEA and significantly so until “W” when the Chinese surnames start to catch up.

This means that if two co-authors – one of Chinese ethnicity and the other not – meet randomly and generate an idea for a project the Chinese author would likely be listed last in an alphabetic ordering. If the Chinese co-author works at one of the public universities then they would get no credit for the idea if they proceed. More likely they would be discouraged from working with the other person at all.

What should be done then? It is best to evaluate academic research output on a combination of quantitative evidence and subjective evaluation. The latter is important because two papers, even if published in the same journal, may have different impacts on the future of research. Thus, it is best to combine numerical measures of research output with evaluations by outside experts in the field. However, if a hard-and-fast numerical criterion is needed then weighting co-authored papers by one divided by the number of authors would provide better incentives for collaboration and not place Chinese academics at a disadvantage.

Footnotes:

- These were the single “Please Please Me,” the Please Please Me LP and the single “From Me to You” according to The Beatles Recording Sessions by Mark Lewisohn, 1988, New York: Harmony Books.

- Some universities also give credit (although not as much) to the corresponding author even if they are not the first author.

- Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (1979). “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk,” Econometrica, 47, 263 – 291.

- Data downloaded from http://www.china-ces.org/Membership/Default.aspx. To perform the analysis I removed the 60 names of people that appeared to be of non-Chinese ethnicity. This yielded 285 names in the sample.

- Data downloaded from http://www.aeaweb.org/Annual_Meeting/assa_programs/. There were 3,971 attendees for the conference.