Will India’s new Prime Minister Narendra Modi change India-China business relations?

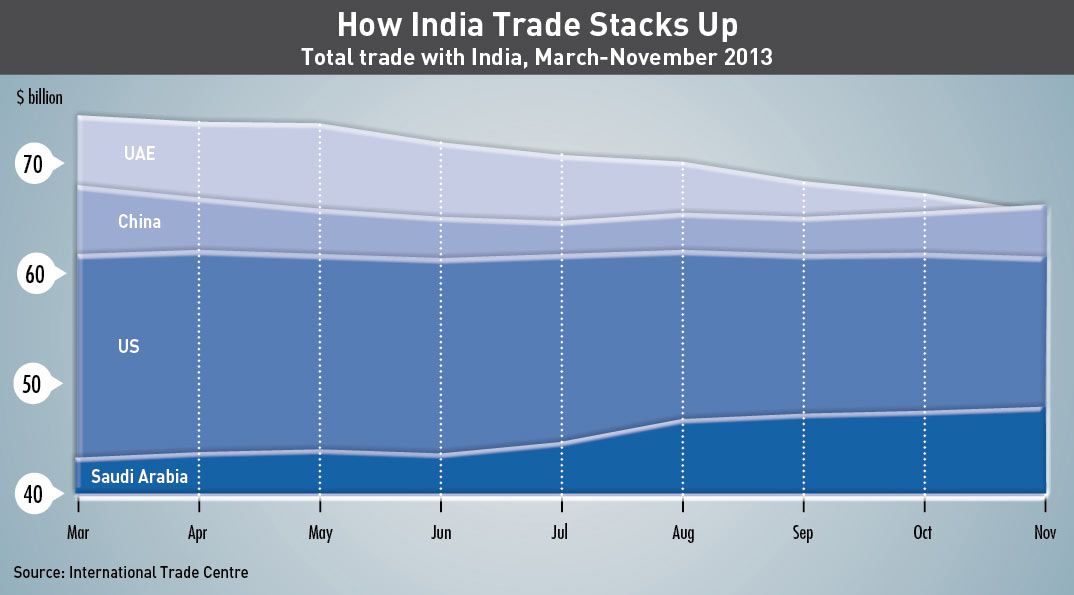

The ancient Silk Road was a treacherous route, beset by bandits, dangerous mountainous paths, and dizzying altitudes. The southwestern route of the road crossed through the Himalayas to link the ancient civilizations of East and South Asia. For centuries, intrepid traders braved the dangers to carry silk, medicines, jewels, gunpowder, and other precious goods between present-day China and India. Today, the two giants of Asia might seem like natural partners—both have huge domestic consumer markets, and complementary specialties, with China excelling in manufacturing and India in services. But while trade between the two economies has risen sharply in the last decade, it remains relatively small given the countriesʼ massive economies. Bilateral trade between India and China grew from less than $3 billion in 2000 to $65 billion in 2013—yet that number still seems minor compared to the $569 billion in goods and services that the US and China exchanged in 2013.

Much of the reason for the modest size of trade has been Indiaʼs economic challenges, including a stagnant economy, copious red tape, and a weak manufacturing sector. “Right now, the dominant view in China is that they see India as discombobulated, and well behind them in terms of development,” says Christopher Johnson, the Freeman Chair in China Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a think tank in Washington, D.C. Relations between China and India have also periodically been tense, due to the legacy of a 1962 war over their shared border.

Yet the Sino-Indian relationship may be nearing a turning point. The election of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in May presented a new opportunity for refiguring the India-China relationship in terms of mutual gains. Modi has promised to adopt a pragmatic attitude toward foreign investment and partnerships in an effort to reinvigorate Indiaʼs economy. In Modiʼs first few months in office, he met with Chinaʼs president Xi Jinping, on the sidelines of a summit in Brazil. Chinese officials including Li Keqiang, the premier and No. 2 leader, and Wang Yi, the foreign minister, also traveled to India to meet Modi. After his trip, Wang commented: “China-India cooperation is like a massive buried treasure waiting to be discovered.”

Many companies are likely to unearth the rewards of this relationship in the years to come. By 2020 or 2025, China and India may be two of the worldʼs three largest economies. India could benefit from absorbing some of Chinaʼs manufacturing capacity and infrastructure expertise, while Chinese companies could discover a new supply of low-cost labor and a vast consumer market in India. A handful of innovative Chinese and Indian companies are leading the way, carving out a new Silk Road for others to follow.

India’s Deng Xiaoping?

The results of the Indian election, which concluded in May, were a strong sign of the Indian peopleʼs desire to break with the past. The Indian National Congress, the party that has run India for most of its post-independence history, was firmly thwarted, while Modiʼs opposition party stormed into power with a landslide victory. The results demonstrated just how dissatisfied Indians were with the sluggish economic growth, persistent inflation, and rampant corruption of the past five years.

Modiʼs government has variously promised to create jobs, balance public finances, build out infrastructure, rein in inflation, and boost Indian economic growth to 7-8%. Clearly, achieving these ambitious targets will be no easy task, and critics question whether he can really eliminate Indiaʼs long-standing inefficiencies.

One of Modiʼs main goals is to boost Indiaʼs weak manufacturing sector, which contributes only 15% of GDP and about 11% of jobs. (By comparison, manufacturing accounts for 32% of Chinaʼs GDP.) Due to its lack of manufacturing capacity, India imports a huge variety of goods and sustains a large trade deficit.

The main reason for weakness in the Indian manufacturing sector stems from the countryʼs strict labor, land, and tax laws, which respectively make it difficult for companies to terminate workers, acquire new land, and transport goods across state borders. Poor infrastructure also makes it hard to get Indian products to market. While China ranks 60th in the World Bankʼs ʻEase of Doing Business Index,ʼ India comes in at a lowly 120.

“India sometimes runs an obstacle course for investors,” says Girija Pande, the executive chairman of Apex Avalon Consulting Singapore and the former Asia-Pacific chairman and CEO of Tata Consulting Services, where he was responsible for crafting China strategy.

Shanghai Urban Construction Group Corporation (SUCGC) is one company that got stuck in this obstacle course. In 2012, the Chinese company won a contract to build part of a new 9.37-kilometer subway tunnel in downtown New Delhi in partnership with Larsen & Toubro, Indiaʼs largest engineering and construction company. SUCGC had plenty of experience to finish the job: it was one of the primary builders of Shanghaiʼs 439-kilometer and 12-line subway network, as well as a builder of subway lines in Singapore.

Unlike in Shanghai and Singapore, however, the Indian subway construction project was bogged down with red tape and delays. Because the New Delhi line runs below a railway line, the project needed approval from the Indian railways bureau, a requirement that kept the companyʼs machines immobile for months in 2013. According to company managers, obtaining work visas for SUCGCʼs Chinese employees was another problem. The process could take up to two years, and many applications were rejected, sometimes forcing it to refigure its operations.

Modi has promised to dismantle some elements of this obstacle course in order to stimulate labor-intensive manufacturing. Yet, perhaps because of political challenges, the governmentʼs first budget, presented in July, failed to address the binding constraints to manufacturing in India, namely the regulation of key factors of production such as land and labor, as well as specifics on tax reform, says Milan Vaishnav, political analyst in the South Asia program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

There is much at stake in these reforms. A streamlined India could absorb some of the manufacturing that is exiting China—especially given Indiaʼs huge, young labor force. Chinese growth has resulted in steadily increasing wages over the past few decades, gradually making low-end manufacturing less competitive in China. At the same time the Chinese population is aging and its workforce shrinking. Aware of this economic shift, the Chinese government is trying to promote the growth of the domestic service sector—which generally requires fewer workers and pays higher wages—as well as more high tech manufacturing.

“I do think there is an opportunity here where some of Chinese manufacturing is going to relocate, and some of it could relocate to India,” says Derek Scissors, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute who studies Asian economic issues and trends. “India certainly has the scale to absorb a good deal of it, unlike say Bangladesh or Vietnam. But you need a better Indian market, and [tax laws are] a big part of that, and so are labor laws.”

Infrastructure King

One of Modiʼs biggest proposals is to spur economic growth by building out Indiaʼs notoriously poor infrastructure, including roads, airports, railways, and internet connections. Chinaʼs expertise in building and financing infrastructure projects could play a valuable role in these initiatives as it did in Modiʼs home state of Gujarat, an industrialized state in Indiaʼs west that is seen as a development success story.

Attracted by Gujaratʼs investor-friendly reputation, as well as Modiʼs interest in developing the region as an industrial hub, several Chinese companies invested big in Gujarat during Modiʼs term as chief minister there. For example, Tebian Electrical Apparatus Stock Company, a manufacturer of energy equipment based in Xinjiang, signed an agreement in 2011 to invest about $500 million in a green energy park and a wholly-owned manufacturing facility for energy equipment in Gujarat, according to local media.

“Part of the big boom in Gujarat over the past few years has been the infusion of Chinese investment, and I would guess that Modi sees this as a key to the growth that happened in Gujarat and why he was able to have such positive impacts there,” says Anish Goel, Senior South Asia Fellow at the New America Foundation, a think tank. “And if he is smart he wants to replicate that on the national level.”

Cross-border investment between India and China is rising, but it is still at a very early stage, says Haiyan Wang, Managing Partner of the China-India Institute. Chinaʼs total foreign direct investment (FDI) in India is only $800 million, representing 0.2% of Chinaʼs total FDI stock. Meanwhile, Indiaʼs FDI stock in China is $500 million, or 0.4% of its total FDI stock. “Thatʼs hardly anything,” she says.

But Chinese investment in India could increase significantly, for several reasons, says Wang. Flush with cash from its export sector and large trade surplus, China is willing to provide low-cost financing to its business partners. In addition, because many of the banks and companies that provide financing are state-owned, Chinese companies tend to have a much longer time frame for making projects profitable.

Indians are likely to reject some Chinese investment in infrastructure due to security concerns. But even so, there is ample opportunity. While China may be barred from owning a train network, a Chinese company could easily set up a coach manufacturing plant, or help lay railway tracks, says Anil Gupta, a professor at the Robert H. Smith School of Business at University of Maryland.

Chinese companies can also ease mistrust by entering the market through joint ventures. Shanghai Electric operates a manufacturing plant in India through a 50:50 joint venture with Franceʼs Alstom, while SUGCG won its bid for Indian subway projects through a joint venture with domestic builder Larsen & Toubro.

The extent to which Chinese companies take advantage of these opportunities will depend on whether India can create an investor-friendly environment. Says Gupta, “If Indian companies themselves are not investing in India, why would anyone else?”

A New Silk Road

There are two main ways Indian and Chinese companies can operate in each otherʼs markets, says Gupta: a company can either directly enter the foreign market, either as a wholly-owned foreign enterprise, or it can acquire a multinational with pre-existing operations there. This latter strategy has proven to be an effective way for India and China to overcome their relatively weak consumer brands. One case in point is the auto market, which has boomed in China over the past decade and is set to do the same in India. Tata Motors, Indiaʼs first domestic automaker, purchased Jaguar Land Rover from Ford in 2008. Chinese auto maker Geely followed in its footsteps by buying Volvo from Ford in 2010. Both acquisitions greatly increased the potential sales that each company could expect in the otherʼs country.

“What is the possibility that Indians would welcome a car from China branded Geely? The probability thinking as a business strategy person is zero, end of discussion, letʼs talk about something else,” Gupta says. “But if Geely buys Volvo, is there a chance that a Volvo car could do very well in India? The answer is yes.” The situation is the same for Tata Motors selling a brand like Jaguar Land Rover in China, he says.

MNC acquisition offers a useful model for how many Chinese and Indian companies may ultimately enter the other market in the years to come. But increasingly, Indian and Chinese companies are also developing the skills to go-it-alone in each othersʼ markets.

This approach typically requires the company to localize its products and services, hire local talent, and find reliable joint-venture partners. Beyond that, India and China present unique challenges. “India has complained for over a decade of market access issues in China, where it sells mainly commodities and raw materials,” says Reshma Patil, the author of Strangers Across the Border: Indian Encounters in Boomtown China. “The Chinese tend to complain about Indian visa procedures and security concerns raised in India about Chinese telecom companies.”

Indian firms looking to enter China find that many sectors of the economy remain completely or partially closed to foreign investment. However, China has rolled out the red carpet for a narrow range of industries that are seen as strategic in developing the domestic economy—particularly services and information technology (IT), sectors in which India excels.

Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), the IT consulting arm of Indiaʼs Tata Group, found its way into China in 2002, through a Chinese government initiative aimed at encouraging the development of a global off shoring base. Then in 2008, the company formed a joint venture with the Chinese government to provide IT training services. TCS now has about 3,000 employees in China, 97% of whom are locals.

Sujit Chatterjee, the President of TCS China, says that one reason for the companyʼs success is that it has paid attention to the deep underlying interplay between its clients and the government in China. “For any organization to succeed in China, you need to understand that interplay. You need to be playing across the local government setup, the customer organization, as well as from a social stakeholder perspective,” he says.

NIIT, an Indian IT training and software services company that came to China in 1997, credits its success to a similar approach. It saw a need in China for better IT training in universities, and worked with the government to expand its business, both by setting up independent training centers and embedding its training in university curriculum.

Prakash Menon, the China President of NIIT, cautions that foreign companies need to remain flexible in the China market. Even companies with successful business models will find that their models only last five years in China, says Menon. Either their success will attract a flood of local competition, or a government policy will suddenly change, forcing them to adapt. “The whole trick in China is how to be very nimble-footed. You should be able to run, and if something comes your way, you should be able to make a turn, work out something quickly, and move on.”

China also tends to be very non-transparent, says Menon. Many top-shelf Indian companies, which successfully work with major Western clients, have so far failed to win the business of Chinese state-owned enterprises. “You may have a better product or service, but you may never sell. There is an invisible kind of a reason why you donʼt sell. Itʼs not just Indian companies, many foreign companies are completely baffled about how this works,” Menon says.

In contrast to China, Menon describes the Indian market is much more transparent, but even more complex. India also has significant barriers to many types of FDI, though Modiʼs government has eased some restrictions in a bid to boost the economy and create jobs. But the real challenge for foreign companies in India is that the Indian consumer market is complicated and fragmented, with many different cultures, religions, and languages—so much so that developing a single strategy for the country often proves impossible.

Telecoms equipment maker Huawei was an early Chinese entrant into India in 2000. Its journey was not an easy one: it found the Indian telecom market to be crowded, with a deep suspicion of Chinese political intentions and product quality. Huawei worked to overcome these suspicions by building large R&D and service centers in India—including a 5,000-seat R&D center in Bangalore and a manufacturing facility for network optical equipment in Chennai—that operated with almost solely Indian employees. The company tried to source as many components from India as much as possible, both to cut costs and avoid criticism. Huawei also sought to address the Indian governmentʼs security concerns by being one of the first multinational telecom vendors to offer the source codes for its network and products to Indian officials, says Suresh Vaidyanathan, spokesperson for Huawei India.

Despite these efforts, tensions remain high. In February 2014, the Indian government launched a probe into allegations that Huawei had hacked the telecom networks of state-run phone company Bharat Sanchar Nigam. But because Huawei has been operating in India for 14 years and is now a significant employer—95% of its 6,000 employees are locals—the Indian government seems unlikely to ban it altogether.

Following Huaweiʼs lead, other Chinese technology companies are feeling out the Indian market. For example, UCWeb, a Chinese company that develops internet browsers for smartphones and was fully acquired by Alibaba in June 2014, has captured about a third of the local browser market since entering India in 2011, according to tracking by StatCounter. In August 2013, the company surpassed Opera to take the number one spot in Indiaʼs mobile browser market.

Companies like UCWeb and Huawei that have built strong mobile businesses in China are likely to look to India for growth in coming years. According to tracking by International Data Corporation, India was the fastest growing smartphone market in Asia in the first quarter of 2014, recording year-on-year sales growth of more than 186%. The market still has much room to grow, with only 10% of Indians owning a smartphone.

However, that 10% is enough to cause a stir of activity around Chinese phonemaker Xiaomiʼs Mi 3 model phones, which in its second fl ash sale in mid-August through Bangalore-headquartered ecommerce company Flipkart, sold 15,000 units in two seconds, as Xiaomi reports it. Whatʼs key about the clamor for Xiaomi phones is that it really marks the first time a Chinese smartphone is taken for something of intrinsic value, as opposed to simply cheap and available.

On the software front Tencent is also scoring one for the home team. According to the Best of 2013 list on Appleʼs App Store, WeChat is the top non-gaming app in India and the second most downloaded app overall.

If Xiaomi and Tencent can ride the wave of positive attention, it could signal an initial breakdown of the stigma associated with Chinese products in India.

The Long Road to Partnership

While the Sino-Indian relationship looks ripe with opportunity over the next decade, many challenges remain. Case studies such as TCS, NIIT, Geely, UCWeb, Huawei and Shanghai Urban Construction Group Corp provide a useful roadmap to new opportunities in foreign markets. But forging a closer Sino-Indian business partnership will entail revamping and improving the Indian economy and infrastructure, and removing restrictions to foreign investment on both sides.

It will also require overcoming lingering mistrust between the two Asian giants, which has especially bloomed in India as Chinaʼs economic, political, and military power has grown. A recent Pew poll found that only 35% of the Indian public had a favorable view of China; 41% and 22% said their opinion was unfavourable and very unfavorable, respectively. Patil, the author of Strangers Across the Border, argues that Sino-Indian economic engagement cannot substantially improve until both sides improve their political relationship, ease strategic distrust, and enhance the mutual cultural understanding.

Yet if there was ever a moment to look for closer Sino-Indian relations, it is now. Modiʼs unprecedented rise to Indiaʼs highest office has demonstrated the Indian publicʼs eagerness for pragmatic policies that will reinvigorate the economy. According to Menon of NIIT, the climate for investment in India “suddenly and spectacularly changed” after Modiʼs election. “The hope in India is that there will be, probably in the next six to eight months, changes in legislation which would open [India to industry] a little more.”

The road to China looks similarly bright for Indian companies. The TCS China President and CEO says that, given the Chinese marketʼs size, potential and growth rate, “there is not much choice about being in the Chinese market or not”. Indian companies that want to be considered major global businesses should enter China sooner rather than later, he says. “On the aspect of timing, in my opinion, it should be done today.”