Business for Haidilao has surged ahead, despite the pandemic. What makes the hotpot chain unique?

Business for Haidilao has surged ahead, despite the pandemic. What makes the hotpot chain unique?

The pre-pandemic sight of diners lining up for spicy hotpot at Haidilao restaurants returned quickly to China once the chain reopened most of its outlets in March. But it didn’t stop there—even as the world reeled from the impact of COVID-19, Haidilao kept adding new hotpot stores, not only in china but in locations around the world.

Over the past quarter-century, Haidilao has become one of China’s few homegrown restaurant chain success stories, and it now has a presence in ten countries outside Greater China, including Australia, Canada, Singapore, Japan and the United States.

While the company has set its sights on global expansion and has made inroads in many countries, the jury is still out as to its chances of becoming a major international brand on par with the likes of McDonalds and Starbucks. Much will depend on whether diners in the West embrace the idea of Chinese hotpot as well as Haidilao’s “above-and-beyond” customer service approach.

Meals and manicures

Haidilao is China’s largest dining chain serving hotpot—basins of simmering spicy broth in which diners cook their à la carte-ordered meat and vegetables tableside. The experience is communal—like roasting marshmallows around a campfire—and ubiquitous in China. But what has made Haidilao a hit—with revenue approaching $4 billion in 2019—has more to do with its ambience and attentive customer service than its selections of abalone, condiments and, Sichuan-style crispy fried pork.

The appeal of Haidilao starts from the moment one enters a restaurant—patrons queuing for a table are waited on hand and foot, pampered with a barrage of complimentary services including free snacks, board games, shoeshines, hand massages and manicures intended to make even the waiting time part of the experience.

Diners continue to be indulged once seated. Warm towels, hair bands, splashguards for smartphones and aprons are all handed out before the first dish is delivered. Diners are treated to spectacles such as noodle-pulling breakdances and Sichuan “face changing” Opera.

Haidilao effectively leaves nothing to be desired, according to Joel Silverstein, founder of East West Hospitality Group and who has more than 35 years of experience operating restaurants in the Asia-Pacific. “All of it basically means value for money,” he says. “They’ve gone well beyond other Chinese restaurant chains.”

Sitting in a Haidilao restaurant in central Tianjin in late October, with the temperatures outside in the low single-digits, Belinda Liu says she dine at her local branch at least twice every month, the 26-year-old beautician attributed her repeat visits to both the taste and service. “The broth, meat, vegetables and dishes are all good, but I come for the service above all else,” she says.

Haidilao’s success has helped husband-and-wife founders Zhang Yong and Shu Ping claim the title of the world’s richest restauranters, thanks to their 68.16% holding in the Hong Kong-listed company. The Sichuan natives—now Singaporean citizens as well as graduates of CKGSB’s MBA program—were worth $30 billion at the time of writing in early January, nearly quadruple the $7.9 billion when Haidilao went public in Hong Kong in September 2018. And with a market cap of $44 billion, the food service giant now is more valuable than Western names such as Restaurant Brands International, Chipotle Mexican Grill and Yum! Brands.

The COVID-19 pandemic, still raging in some parts of the world but largely subdued within China, did initially knock Haidilao’s growth, but business has fared better than most rival chains. Revenue slumped 19% year-on-year in the first half of 2020, compared with declines of 23% for Jiumaojiu Group, 29% for fellow hotpot chain Xiabu Xiabu and 43.5% for Ajisen Ramen.

Humble beginnings

Zhang’s story, from factory worker to billionaire restaurant mogul, is a classic rags-to-riches tale that speaks to the entrepreneurial zeal of modern-day Chinese society. After a six-year stint at a tractor factory and a couple of failed attempts at entrepreneurship, Zhang—then a 19-year-old high school dropout—got into the restaurant business with his then-girlfriend-now-wife Shu and another couple, Shi Yonghong and his wife Li Haiyan. The chain began as a four-table cafe that opened in 1994 in rural Jianyang—a city near Sichuan’s provincial capital of Chengdu renowned for its mutton soup.

“I was penniless, so the others were the real investors, although the entire investment was less than RMB 10,000 yuan ($1,514),” Zhang said in an interview with China’s Economic Observer in 2011.

Since that first humble mom-and-pop shop, Haidilao has grown at a dizzying rate, reflecting co-founder Zhang’s philosophy that “it’s better to scale fast and be everywhere instead of having a single towering presence.” Haidilao expanded beyond Sichuan for the first time in 1999 to Xi’an, capital of Shaanxi province. The venture failed after just six months at a cost of RMB 700,000.

The company then opened stores in Henan province in 2002, Beijing in 2004 and Shanghai in 2006. The first overseas branch opened in Singapore’s touristy Clarke Quay at the end of 2012, and then the US in 2013. Haidilao opened its 100th outlet in 2014 and operated 300 eateries by the time it listed in 2018. It has more than tripled its store count since then.

Serving up a winner

Hotpot restaurants are as abundant in China as burger joints are in the US—one estimate placed the number at more than 700,000 at the end of 2019—and Sichuan-style hotpot is easily the nation’s most popular eat-out cuisine. But Haidilao is not just adored by spicy hotpot aficionados; in fact, its business model is held up as an example in China. A Tsinghua University case study about Haidilao in 2011 likened the cook-it-yourself food preparation to Ikea’s assemble-your-own-furniture model, while teams of government officials even visit the restaurant chain to learn tips on how to truly “serve the people.”

What has helped Haidilao cut through the noise of all the other hotpot operators is extraordinary customer service in a country where “good service” is a relative term. “Their overall rankings are not much better than other hotpot chains, their food quality not necessarily better, but service is their main point of difference,” says East West Hospitality Group’s Silverstein.

Another aspect of Haidilao’s winning formula is its corporate culture. “People in the hospitality sector say that Haidilao was one of the first private companies to create a ‘family’ culture within the company, well before Alibaba, Zappos and others started,” says Kitty Smyth, founder of China strategic advisory firm Jingpinou.

Haidilao is renowned for its generous compensation system for employees from top to bottom, and the company has a higher-than-industry retention rate. For example, while restaurant managers are rewarded with up to 3.1% of their location’s profits, they also receive a cut of the profits at stores managed by their first- and second-generation apprentices. This profit-sharing scheme incentivizes managers to mentor talented staff to prepare them for management, helping to accelerate the pace of new store openings. New hires can work their way up to manager regardless of background within four years.

“Haidilao grew their managers from the bottom ranks up, and that gave the company stability and loyalty from employees, creating a solid foundation for expansion,” says Smyth, who has supplied Haidilao with pork from Ireland and the UK.

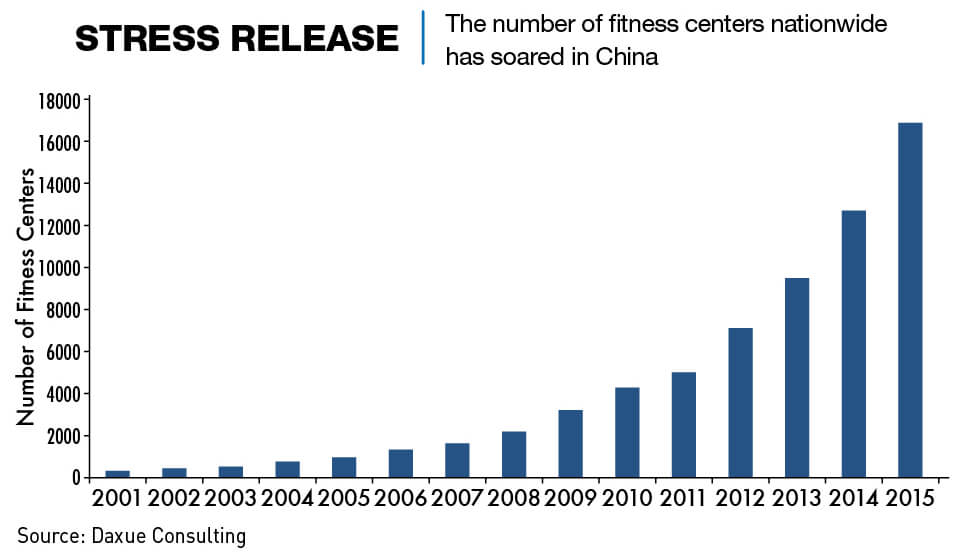

Two major consumer trends buoyed Haidilao too. The first is that Haidilao’s boom in the early 2010s coincided with the exponential rise of social media—particularly Tencent’s WeChat, which was launched in 2011. “Haidilao skews to a much younger audience with all of their WeChat postings,” says Silverstein. “Early on, they had strong viral marketing on the internet. People went to Haidilao, posted it on their WeChat Moments and their friends became interested.”

The second is China’s passion for hotpot, which held a 13.7% share of the domestic cuisine market in 2017, according to independent research cited by Haidilao in its listing prospectus. The second-largest share was Sichuan food with 12.4%, followed by Cantonese with 8.2% and Jiangsu-Zhejiang cuisine with 6.3%. “Sichuan spicy food has been a preference of younger consumers for years now. That trend is not going away,” says Silverstein.

That may have something to do with the simplicity of hotpot, which is easier to standardize and replicate compared with other Chinese cuisine types. Hotpot restaurants like Haidilao can make do with smaller kitchens to prepare ingredients ahead of time. “Hotpot is the easiest type of Chinese food to execute. It’s very scalable,” says Silverstein. “The labor costs are low because the customer does the cooking most of the time.”

Stumbles along the way by the company have been turned into opportunities to learn and improve. After three restaurants in Beijing and Singapore closed temporarily in 2017 over questionable hygiene, Zhang pledged to use technological advances to avoid future food scandals. The hotpot chain made good on the promise a year later by opening a “smart restaurant” in Beijing that included an automated kitchen, replacing chefs with robotic devices to prepare and serve food, and an automated warehouse that operates in temperatures too cold for pests to survive.

But the high cost and difficulties of retrofitting existing stores with smart technologies has prohibited wider roll out. By the end of June, Haidilao had fitted three restaurants in Beijing with intelligent robotic arms that prepare ingredients and equipped 23 restaurants with automated mixing machines for readying soup bases. Some 958 robot waiters that take orders and deliver ingredients to dining tables were also working in stores worldwide.

“The application of new technology is aimed at improving the customer experience,” says Haidilao spokeswoman Cui Xiawan. “It has optimized kitchen management and improved food safety.” Other tech flourishes that have won over diners include touchscreen ordering on iPads and the ability to customize soup bases based on customers’ requests.

Global ambitions

As recently as 2018, Haidilao’s Zhang predicted the company’s overseas footprint would eventually exceed its China presence. “Much of [China’s] history and customs can be learned through food,” he told Forbes in 2018 to explain the overseas potential of hotpot. COVID-19 has slow down plans to conquer foreign markets but doubts about Haidilao’s global expansion actually date back to 2011.

As recently as 2018, Haidilao’s Zhang predicted the company’s overseas footprint would eventually exceed its China presence. “Much of [China’s] history and customs can be learned through food,” he told Forbes in 2018 to explain the overseas potential of hotpot. COVID-19 has slow down plans to conquer foreign markets but doubts about Haidilao’s global expansion actually date back to 2011.

Nine years on, just how much of an international success Haidilao can be remains to be seen. In Europe, the US and other Western markets, Chinese hotpot barely registers as a dine-out option. “Brand awareness of Haidilao outside of China and outside of overseas Chinese, is low,” says Smyth from Jingpinou. “Understanding of hotpot as a cuisine and of the fun, social experience of hotpot, is also missing.”

“There will need to be an advertising strategy that introduces people who haven’t eaten hotpot before to the joys of hotpot. They will have to start at the beginning, in much the same way KFC did when they first went into China.”

Elements that drove Haidilao’s success in China will work against its quest to become a global behemoth. A meal at Haidilao is a more formal setting, with a higher price point and a more varied menu, so any global expansion would be slower than that of the Western fast-food chains. Brands such as Burger King, KFC, McDonald’s and Starbucks crept into markets via off-the-shelf franchises, whereas Haidilao establishes and manages its own restaurants.

“I don’t believe it’s going to be a big international brand,” says Silverstein. While the chain has promise in markets where spicy hotpot is already popular, such as Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam, prospects in the West are likely to be limited to where there are considerable Chinese or Asian communities.

“There’s not much of a global opportunity, but that doesn’t mean they can’t do 50 stores in the US, for example. There are enough ethnic Chinese enclaves to be able to have a business but it’s not going to be a major chain.”