Having established their dominance at home, leading Chinese tech companies are increasingly turning their gaze overseas

Lenovo CEO Yuanqing Yang celebrated the tech company’s acquisition of a Chicago-based smartphone brand in October 2014 in a distinctly Chicago way. His firm had just closed its purchase of Motorola Mobility from Google for $2.91 billion plus roughly 6% of Lenovo’s shares. To mark the occasion, Yang, another executive and the smartphone firm’s president chowed down a deep dish pizza decorated with a Motorola logo.

Lenovo’s purchase was just one overseas acquisition in a busy year for China’s technology industry. China Mobile invested more than a billion dollars in telecom companies in Pakistan and Thailand; Lenovo spent $2.3 billion on IBM’s low-end server business in the US; Huaxin bought 85% of French telecom company Alcatel-Lucent; Alibaba spent $220 million for a 20% stake in mobile video app Tango and joined in a $250 million fundraising round for car service Lyft; and Baidu invested in Uber and opened a $300 million research and development (R&D) center in Silicon Valley to take advantage of local talent—to name just a few.

Analysts have been hesitant to label this a trend, but there are reasons to believe that China’s recent boom in outbound tech investment will continue. China’s tech sector is flush with cash, and the increasingly competitive domestic market has left companies anxious to acquire new technologies and capacities abroad in order to compete at home.

“Some people are going to be tempted to say the government has been pushing this for a long time, investing at home but also overseas, but I don’t think it’s really that,” says Michael Clendenin, founder and Managing Director of China-based research company RedTech Advisors. “It’s just business 101. Look everywhere you can under every rock for any type of resource that is going to help you further your business goals. It just so happens that Chinese tech companies are… looking under rocks all over the world.”

Powering the Boom

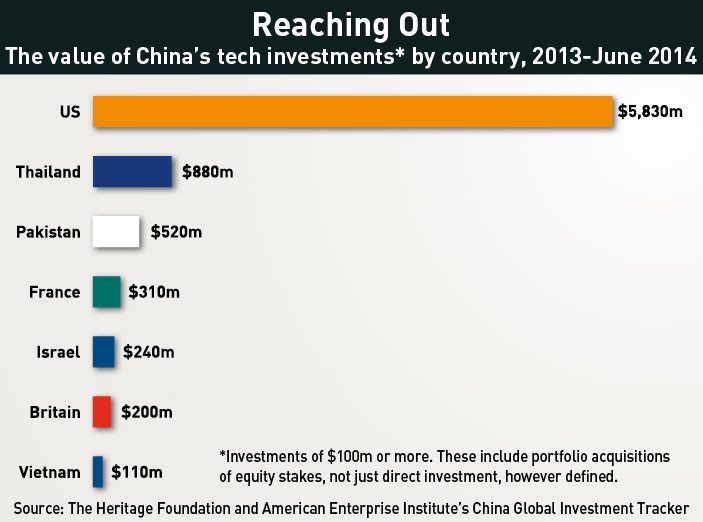

China’s investments abroad have in recent years continued to ramp up sharply, creating huge opportunities for partnership with foreign companies. Chinese outbound direct investment grew from $2.7 billion in 2002 to a stunning $102.9 billion in 2014, according to data from the Chinese Ministry of Commerce—a nearly 40-fold increase in only 12 years.

The potential for future investments is huge: Rhodium Group, which monitors Chinese outbound investment, estimates that over this decade Chinese outbound investment will reach up to $2 trillion. The government projects that outbound investment will soon be larger than foreign direct investment (FDI) into China, as Chinese firms increasingly venture out.

Chinese companies go abroad in search of resources their home country lacks, says Derek Scissors, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute who studies Chinese investment. “They’re going out, which is what firms classically do, and they’re looking for stuff they don’t have at home.” According to Scissors, this includes natural resources, advanced technologies and even the stronger legal systems and property rights of advanced countries. Chinese companies with particularly cutting-edge technology may choose to invest abroad and develop new patents there, to avoid China’s notoriously lax environment for intellectual property rights.

Furthermore, fast growth in their home market has also given Chinese companies ample cash reserves: they are looking for opportunities to invest and diversify their portfolios. And the global financial crisis has made assets in many developed countries much cheaper.

Meanwhile, China has been gradually relaxing its regulations governing outbound investment, giving private companies and individuals more opportunity to invest abroad. Private sector firms accounted for more than half (59%) of China’s total transaction value in 2011 and 2012, and 70% of Chinese FDI in 2013, according to Rhodium Group.

China’s early efforts at going abroad—beginning with the zouchuqu, or “going out” strategy, in 1999—focused solely on state-owned enterprises. Other businesses and sectors were still subject to tight regulations. But China’s outward FDI regime has loosened significantly in recent years, removing many restrictions and red tape.

Part of the recent increase in technology sector investment is tied to this increasing freedom for private companies. Though they have close relations with the Chinese government, most of China’s big tech companies are not state-owned. “If you look at the main internet players, and the tier-two internet players, 95% of them are totally private,” says Clendenin of RedTech. “And that’s just a totally different mentality—you’ve got to survive at any cost because you’ve only got yourself to rely on… So I think these guys are naturally more open to looking overseas.”

Chinese technology companies are looking for a variety of things in their investments and acquisitions abroad. They may take controlling stakes or minority stakes in foreign companies to access new markets, to acquire useful technologies, capabilities or talented personnel, or just to diversify their investment portfolios.

Of all these goals, accessing new markets typically offers both the highest risks and highest returns. As Joel Backaler, the author of China Goes West and a director at Frontier Strategy Group, says, “There [are] some very real business reasons why these Chinese companies, particularly tech companies, are going out. The market [especially for smartphones or consumer electronics] is highly competitive within China. Therefore if you can take that kind of product and adapt it for other markets, it can be a good way to diversify your business and maintain your margins.”

Chinese companies have tried their hands at both developed and developing countries. Companies operating in the former, such as Huawei, the telecoms manufacturer, and Wanxiang, an automotive parts maker, have had success focusing on hardware. While Baidu and Xiaomi, a company best known for its smartphones, have targeted the latter, with Baidu focusing on Southeast Asia, the Middle East, North Africa and Latin America.

But trying to carve out new market share is often extremely challenging. As Clendenin points out, accessing new markets requires successful product localization, integration of home staff in the target country, and overcoming the major local or international incumbent.

Compared with other types of investments, the success or failure of a bid to capture foreign market share is much more obvious, and attempts to win market share abroad have led to some of China’s most notable failed acquisitions—from TCL Corporation’s failed acquisition of France’s Thomson Electronics, to Huawei’s repeated blocked bids on US technology and telecommunications projects.

Study Abroad

According to Clendenin, Chinese companies are far more likely to succeed in foreign acquisitions if their ultimate goal is advancing in the Chinese market, where they have a lot more local knowledge and there is still great potential. “Invest to learn, don’t invest to grab market share in a foreign country where you know nothing about the market.”

This strategy seems to be increasingly the norm in the tech industry, with Chinese companies making investments to soak up strategic technologies, capabilities, talent and brands that they can then take home.

Both Backaler and Clendenin cite Tencent as an example of a company that has successfully advanced its position at home through investments and learning abroad. Tencent has long been known for rolling out its own versions of other companies’ successful services, including everything from ICQ to FarmVille. In 2010, Charles Zhang, the CEO of rival web portal Sohu.com, dismissed Tencent as “a company that doesn’t create anything”. In the last five years, however, Tencent’s copycat model has become a lot more legitimate—instead of copying, now it often tries to acquire them.

In 2012, Tencent invested $63.7 million in KakaoTalk, a Korean mobile messaging app. Unlike many mobile companies, KakaoTalk has successfully developed monetization strategies, including offering emoticons and games, features that have already begun to influence Tencent’s mobile chatting app, WeChat. Tencent’s acquisitions of foreign gaming companies like Riot Games and Epic Games were also directed at acquiring titles they could introduce at home. “They’re essentially identifying hot games in the US market and then localizing them for the Chinese market,” says Backaler.

Some of Baidu’s recent acquisitions suggest the company is also interested in “studying abroad”—for example, its purchase of a minority stake in the Finnish company IndoorAtlas in September. IndoorAtlas makes a cutting-edge mobile product that allows users to map and navigate indoor spaces. Its President Wibe Wagemans explains how it could enable people to “find a friend indoors. You could find a booth or a product at a conference. You could search for shoes in the mall and it would take you all the way to the actual shelf.”

The technology could have big potential for Baidu, which controls roughly 80% of the mobile search market in China and a little more than half of the market for mobile maps. “We’re looking to introduce that technology into our existing product line,” Kaiser Kuo, Baidu’s Director of International Communications, says of IndoorAtlas.

It’s not just the Chinese companies that learn something. In fact, they now have a lot to offer to foreign counterparts, in addition to the ample cash and access to the Chinese market.

In a post on the website Medium, Ted Livingston, founder and CEO of Kik, a social messaging app, wrote about his and others’ desire to learn from Tencent’s WeChat. “If you talk to me, or to Evan Spiegel [CEO] at Snapchat, we’ll say the same thing: we want to be the WeChat of the West,” he wrote. Tencent invested $60 million in Snapchat in 2013.

“They’re very innovative,” Allan Young, the founder of a San Francisco-based technology incubator called Runway, says of Chinese internet companies. “They’re better than we are at building games and monetizing those games. Their viral coefficient is higher than our viral coefficient… I think in some areas of mobile, Chinese companies are stronger, smarter and faster.”

There are still other reasons Chinese companies invest abroad: as Allan Young of Runway points out, the primary goal is not always advancing the technology of the investor. Sometimes, “it’s to invest in companies they feel are relevant to their industry and they could help grow and make more valuable.” This is the strategy behind ZPark Venture Fund’s investment in California healthcare IT firm HealthCrowd, as well as Bank of China’s loans to Zimmer Holdings, a medical device company based in Indiana.

In other cases, Chinese firms may also seek to tap the talent base and management experience of companies abroad, for example in Baidu’s high-profile investment in an R&D center and artificial intelligence lab in Silicon Valley in 2014. “We want to go where the talent is,” says Kuo. Not every great engineer happens to be located in China. Talent is distributed globally, and R&D should be too.”

The Biggest Stumbling Blocks

In making acquisitions abroad, Chinese companies face myriad challenges. One of the biggest is simply a lack of experience managing and operating in foreign markets.

Backaler points out that many of China’s early failed acquisitions were the result of Chinese companies with plenty of money going after assets that were failing for complex reasons. Chinese companies like TCL Corporation “weren’t necessarily in a position to go overseas, let alone to bring a company facing tough times back to life,” he says. He also cites Huawei as another Chinese company that failed to listen to the market, made mistakes in managing its image, and now is essentially barred from doing some types of business in the US.

On the positive side, Backaler says that Lenovo has done a great job of managing its US-based acquisitions. By retaining the acquired company’s management and staff, and only gradually making changes to the business model, Lenovo has convinced its American employees at IBM and Motorola Mobility that it was ready to learn from their experiences and dedicated to managing the company for the long haul.

There are other obstacles to Chinese outbound investments: hurdles to financing and approvals within China, or potential security threats with high-tech investments. However, the biggest obstacle to Chinese outbound investment appears to be connecting interested Chinese companies with potential targets. Very often, investors and investees just don’t know how to find each other.

“I think it’s challenging, because on one hand there is tremendous interest on the Chinese side to go out, and then if you’re looking from the American perspective there’s a strong desire for that investment, however there’s a really big gap in between,” says Backaler. Typically, interested Chinese investors go on tours or attend conferences where they can meet investment targets, and foreign states, cities and other local governments set up organizations inside China to recruit investment. However, both methods fall short of connecting all the interested parties.

According to Young, another related problem is effectively monitoring an investment once capital is deployed. “If they don’t have a mechanism to perform consistent monitoring of their investment… then you’re not fulfilling one of the important functions of being an ideal venture investor,” he says, adding these systems, having a presence on the ground and hiring good professionals are the biggest challenges.

Organizations are evolving abroad as a result. Young says Chinese companies are increasingly relying on a group of professionals in Silicon Valley, often native Chinese with extensive technology industry experience, to build out networks and contacts. And Backaler points to public-private partnerships, like the Greater Washington China Investment Center in Washington, D.C., that are helping potential Chinese investors access the US market.

But there are undoubtedly some who still aren’t hitting the mark. “The short answer is that the investments are fairly opportunistic at this stage, and it’s hard to identify which Chinese companies are really serious… Many [potential investors] are based in third-tier cities and we don’t even really know who they are yet,” says Backaler.

What Will the Future Hold?

The volume of Chinese technology investments is likely to vary a lot from year to year. 2014 was an unusually busy year; 2015 may not be. Still, there are many reasons that overseas tech investment and partnerships are likely to continue to increase. Investment regulations for the private companies that make up most of the technology industry are looser than ever in China, and the competitive Chinese market requires that Chinese companies stay sharp with the latest technological developments. Compared with executives in other sectors of the economy, Chinese technology leaders tend to be younger and more in tune with the international market, analysts say. Moreover, foreign companies are more receptive to Chinese capital than ever.

In general, the mutual benefits from Chinese collaboration with foreign companies are huge: Chinese interest allows foreign companies to sell assets at a higher price, contributes to funding available for R&D and supports the economy. In the US, for example, Chinese high-tech investments have created or sustained 25,000 jobs in the last few decades, according to Rhodium Group. Many Chinese companies have plenty of cash to invest; they may also offer their foreign partners access to the Chinese market and even innovative technologies.

Wagemans, the president of the Finnish start-up IndoorAtlas, provides a fitting description of the kind of opportunity that a Chinese investor can offer to its invested company. “The beauty about China is the market right now… is moving faster than the US,” adding there is fierce competition going on between the big players in China.

That level of competition, the sheer size of the market and the R&D funds available are going to ensure that Chinese companies are going to remain attractive investors for some time to come.